On my last morning alone around the moon, I woke to a breezy blast of mariachi trumpets. With the serene lunar surface gliding by below me, Herb Alpert’s “Tijuana Taxi” was about the strangest music mission control could pipe up over the radio. But still, it got me awake. “Allo, Terre. Salut de l’Endeavour,” I replied in French.

“You can expect that you’ll have some company later this afternoon,” Karl Henize told me. On the surface, Dave and Jim suited up for their final moon walk before they began preparations to lift off and rejoin me. We all had a busy day ahead—even if everything went according to plan. If not, it would be even busier.

My orbital path had drifted during my three days alone, so that I no longer passed over Hadley plain. I fired the engine for eighteen seconds to get back over the landing site. “It looks like a beautiful burn,” Karl remarked, adding that he was also watching the television images of Dave and Jim exploring Hadley Rille. “Save a copy for me,” I requested. I wanted to see it all when I got back to Earth. I glided over the landing site, noticing how much the sun angle had changed in the three days since they landed. The plain was almost in shadow when we arrived. Now the sun was much higher: the plain would be growing warmer.

The scientists following the SIM bay experiments were delighted with the data rolling in. But the equipment was slowly failing. The booms still extended, but began to stick when I retracted them, forcing me to pulse them in short bursts to come in all the way. A sensor in the panoramic camera also acted up, resulting in fewer good images, and the laser didn’t fire as frequently as it should. For new and untried equipment, it had all worked magnificently, but it couldn’t last forever.

Karl told me some exciting news from the scientists in Houston. The laser had measured the height of the mountains, and the X-ray data showed what the mountains were made of. The scientists had already compared the data. It seemed the highest mountains contained the lightest materials such as aluminum. Lighter elements rise in molten lava, so these results strongly suggested that the moon had once been largely a ball of hot lava. It looked like we had just made a major discovery about how the moon formed. Not only that, but it also meant that, unlike Earth, the moon had probably not changed much since it cooled. “It gets rather exciting when the data starts adding up like that,” Karl added. “Lots of things are beginning to fall into place, and what a mission, that’s all we can say!”

I was delighted we had solved a major mystery. To me, that discovery alone was worth the cost of our flight. But now it was time for some more piloting. Back in the lunar module, Dave and Jim prepared to lift off. Ed Mitchell, the lunar module expert, was back as CapCom for this critical time. He read up a blizzard of numbers to me, telling me where and when I would need to rendezvous with my moving target. But then I lost his signal. I thought he was done. For twenty minutes he tried to raise me on the radio while, oblivious, I continued to prepare the spacecraft. With less than one minute to go before I slid around the moon and out of radio contact, Ed and I could finally talk again, and I hurriedly wrote down the last important numbers.

Dave Scott, alongside Neil Armstrong, had made the first-ever docking in the space program on his Gemini 8 mission back in 1966. Dave had refined the technique testing the first lunar module on Apollo 9. Now, around the moon, we’d use those proven techniques to dance a complex orbital ballet to find each other and link up once again. Instead of gradually catching up with each other after a few orbits, we would attempt a direct rendezvous. Falcon would launch, and bam, I’d snag them right away.

We’re all set,” Dave called from the lunar surface. “Ready to give us some warm chow? I tell you, cold tomato soup isn’t too good.” I guess he was fed up with the unheated food they had to eat in the Falcon, and was ready for the home comforts of Endeavour.

“You’re go for liftoff,” Ed radioed to Dave. “I assume you’ve taken your explorer hats off and put on your pilot hats?”

“Yes, sir, we sure have.” Dave responded. “We’re ready to do some flying.”

Back in mission control, Joe Allen paraphrased some poetry by science-fiction writer Robert Heinlein. “We’re ready for you to come back again to the homes of men, on the cool green hills of Earth.” That sounded good to me, too.

On Hadley plain, Falcon’s engine lit, hurling Dave and Jim’s spacecraft upward. They quickly pitched over and zipped along the rille on the curving path needed to reach me.

As they rose, I turned on the cassette player. We were an all–air force crew, so I figured it would be fun to play the air force anthem to mission control to provide a stirring background. Bad move.

Perhaps it was related to the earlier communication problems and mission control was playing it safe, but my radio signal was not only heard on Earth. For some reason, mission control also patched it through to the Falcon. Dave and Jim, intently focused on their checklists, now had distracting music in their ears. The ground didn’t tell me—perhaps they didn’t realize what they had done themselves until later.

Had something gone wrong with Falcon at that moment, the music could have been a dangerous diversion. Fortunately, everything went to plan, and Dave and Jim zipped into an orbit below and behind me. I’d trained extensively to catch them if Falcon lurched into some other wilder orbit. But I never needed to. I soon had a good radar lock on them. Guided by Ed Mitchell back on Earth, Dave and I flew our spacecraft ever closer, mirroring each other’s moves. “You got your lights on, Jim?” I radioed, watching for Falcon’s flashing tracking light.

I looked through the sextant and the telescope to try and find them, but sunlight in the scopes made it hard to see anything. Finally, in the corner of my eye, I spotted a flash of light in the telescope. I manually drove the instruments over to that point, and there it was—a very bright light. “I’ve got your lights now, Dave,” I told them. Soon afterward, on the far side of the moon, Dave spotted Endeavour, a dim star in the distance.

“Oh, you’re shining in the sunlight now. Boy, is that pretty!” I called as we grew ever closer. “I believe I can even make out the shape.”

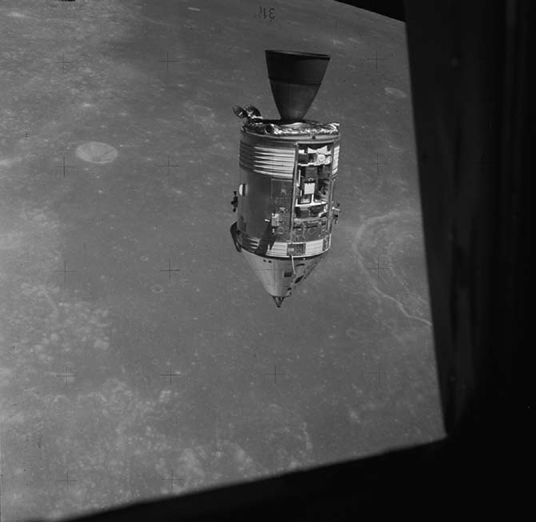

As Falcon steadily rose to meet me, Dave and Jim gave Endeavour an extensive look-over, while I photographed them in turn. Falcon had left its descent stage on the surface of the moon and was now much smaller than when I had last seen it. The lunar module appeared fragile before, but now it looked like I could reach out and crumple it with my fist. Glinting in the sunlight, it was painfully bright to look at.

Dave and Jim get a good view of the SIM bay as we rendezvous in lunar orbit.

Falcon was so light, a pulse of their thrusters rattled them around. So it was easier for me to dock using Endeavour. I slowly slid toward them, so gently that we barely touched. Then, with a touch of my thrusters, I pushed forward into a hard dock.

The rendezvous and docking had been fast, and perfect. “Good show, Endeavour,” Dave radioed to me. “Welcome home,” I replied. That might seem like an odd choice of words—after all, we were still a quarter of a million miles from Earth. But Endeavour had become my home, and Dave and Jim were returning from a great adventure. “The Falcon is back on its roost and going to sleep,” Dave added with a poetic flourish.

I’d kept our home clean and tidy for them. But now, as I opened the hatches between the spacecraft I saw two grimy faces. Their spacesuits were dirty, and I could smell the moon dust in the air. It was a new, peculiar odor to me, dry and gunpowdery. I kept the hatch closed as much as possible while we began to transfer equipment, hoping the floating dust would not spread. I was mostly successful, but the creep of dust was unavoidable. Dave and Jim floated long sample tubes of lunar dirt and boxes of moon rocks through the hatch, which I stowed inside Endeavour under the couches. Mindful of the new rules after the Soyuz 11 depressurization tragedy, we kept our spacesuits on.

While busily running SIM bay experiments, I also stored Falcon’s flight plans and checklists, food, priceless photos in film magazines, and—less priceless to me—Dave and Jim’s used urine and fecal bags. Of all the things to return from the lunar surface, did we really need their crap?

Finally, Dave and Jim floated into Endeavour. I was elated to see them. But Dave didn’t look happy. In fact, while Jim looked away sheepishly, Dave began to loudly berate me about the distracting tune piped into the Falcon during liftoff. Didn’t I know I had jeopardized the whole mission, he thundered, by playing that darn music?

This wasn’t the reunion I had expected. I could only apologize and explain that I had only radioed it to Houston, with no clue they would patch it back to the Falcon. My explanation seemed to satisfy Dave for the moment. I guess he eventually forgave me, because months later at an awards ceremony with the Air Force Association Dave bragged about playing the tune.

There wasn’t time for me or Dave to dwell on the argument. We had too much to do. Dave and Jim were busy ensuring they had moved everything in from the Falcon. But they missed some items. Some of their PPKs, including personal items they had kindly taken down to the surface for me, were overlooked.

We wouldn’t discover that mistake for a long time. Behind in the timeline, we hustled to close the hatches and pressurize our spacesuits. Dave’s suit did not pressurize properly on the first attempt, nor did the spacecraft hatch seal correctly, possibly due to some lunar dust on the seal. After more time-consuming checks, we finally seemed to have the problems solved, and Dave and Jim could remove their helmets and gloves. They had started their day with a demanding moon walk, and they hadn’t eaten for eight hours. They were ready to stop for a while and grab some food.

Then it was time to finally undock from Falcon. “It’s away clean, Houston,” I reported as the lunar module separated with a bang. I felt sad to see it go; it was a magnificent spacecraft. Now it would be steered to a final crash on the lunar surface.

I was also acutely aware that we were now down to one engine. The big engine in the service module was our only way out of lunar orbit. So far, it had worked well, day after day. But if it stopped working.

No point thinking about that. The separation had taken longer than planned, so instead of our scheduled rest break, we jumped back into our chores, including some more SIM bay experiments.

Dave and Jim didn’t seem weary to me, but it was hard to tell when we all had so much to do and were zipping around getting it done. I put Dave’s slight ill humor down to his annoyance with me over the tune.

But then we heard a familiar, gruff voice over the radio, which only got in the loop when there was something important. “This is Deke,” the voice growled to Jim. “I’d like to have you and Dave, at least, take a Seconal here before you go to sleep so you can really power down for the night. You guys need it. It’s up to Al whether he wants one or not.”

Dave immediately looked puzzled. Seconal was a sedative drug we carried on the flight. Why would Deke ask two of us to take it and not all of us? Without an explanation, Dave decided against it. We continued running experiments and stowing equipment. Meanwhile, at mission control the doctors grew alarmed. Watching their instruments, they could see something wrong with Jim’s heartbeat. Both sides of his heart were contracting at the same moment. They’d spotted similar, minor blips with both Jim and Dave while they were on the moon. But this irregularity looked worse. Jim could be heading for cardiac arrest.

The doctors didn’t tell us. Neither did Deke, who simply requested we take the sleeping pills. We only had one other clue that something might be wrong, when the ground told me, “We’d like to make sure tonight that Jim is on the EKG for the evening.” They wanted to keep monitoring Jim’s heart via his biomedical harness. Again, they never said why. By this time, we all felt dead tired and didn’t ask questions.

Jim and Dave would have worked until they dropped, they were so dedicated to the mission. “We’re still trying to get cleaned up in here and get suits put away, and all that sort of stuff,” I told the ground. “It’s awfully cramped quarters, and there’s an awful lot of stuff to move around.” The spacecraft seemed very different now that three of us were crammed in again. “I kind of liked it here by myself,” I added wistfully.

If Jim were having a heart attack, it was about as good a place as he could be—weightless, breathing pure oxygen, wired to a heart monitor. Still, the ground should have told Dave. As commander, he needed all available information about his crew. By the time we got to sleep, I’d been awake for more than twenty-one hours, and my crewmates for twenty-three. If we had known of Jim’s serious condition, we would have stopped much earlier. Instead, we slogged on for three and a half hours after Deke’s call before we finally finished our day. It was later determined that the physical stress of working on the moon, combined with the brutal training before launch, had left Jim’s and Dave’s hearts depleted of potassium.

We felt exhausted and slept deeply for nine solid hours. But it may have been too late for Jim. We can never know for sure, but it is possible Jim’s heart was permanently damaged that day, and the countdown to his premature death had already begun.

The next morning, we all felt much better. Still wary of Jim’s condition, the ground asked him to continue to wear biomedical sensors, instead of a planned switch with Dave. Without an explanation given, Dave overrode the request. He knew how uncomfortable the sensors could be after a number of days and gallantly took Jim’s place.

Because I had changed orbit to rendezvous with Falcon, we now passed over new regions of the moon. “Dave and I are looking like mad and taking pictures,” I told mission control as we glided across the ever-changing landscape. The laser was failing, so we cycled its power switch in a last futile effort to keep it working. I still struggled with booms refusing to retract. Equipment was starting to deteriorate. But with three of us in the spacecraft, we could run SIM bay experiments and take photos out of the window at the same time, so we stayed very busy. I wasn’t too upset about the failing equipment. We’d already gathered so much information, I was just happy with what we had.

With all three of us scrambling to accomplish tasks, my day seemed much more complicated. I felt very happy to have Dave and Jim back alive, but I began to miss working alone, when we didn’t all have overlapping tasks.

We still had a lot of film left, so we eagerly recorded many interesting geological features. While we did, the ground continued to ask cryptic questions about Jim. “Can you guys give us any estimates on the water that you and Jim consumed on the surface,” mission control asked, “and any differences between this and what Al’s been consuming?” Still unaware of the reason for the questions, Dave brushed them off with, “I think that is probably a good discussion for the debriefing after the flight.”

We were once again asked to take sedatives for the sleep period, and once again Dave responded, “I think that’s unnecessary.” The nearest to an explanation we received was, “We are anxious for you all to continue eating and drinking well, because of the EVA yet to come.” If they had told us the truth, we would have shared their anxiety and probably followed their requests.

Instead, oblivious, we continued with our science objectives, mapping and measuring the moon until mission control told us, “You’re ready for sleep and we’ll tuck you in.”

We were up the next morning raring to do more of the same. We zoomed in on the shadowy amphitheaters of crater rims and floors, prying out their secrets with our lenses. “As we go around in lunar orbit,” Dave told our geology team back on Earth, “I could just spend weeks and weeks looking. And I can pick out any number of superb sites down there.” Almost misty-eyed, he continued, “There is just so much here. To coin a phrase, it’s mind-boggling.” I couldn’t have put it better myself.

We were pleased to hear from Karl Henize that our flight was making front page news around the world. Perhaps the public was still interested in moon exploration after all. He also told us that, back in Houston, they’d been soaked with rain all day. “Going to be a lot of grass cutting to do when you get back down here, guys,” he quipped.

“Oh, yeah, but we’ve sure got nice sunny weather up here,” I replied with a chuckle. “It’s just as clear as crystal.” Besides, what did I have to worry about? I lived in an apartment. No lawn.

We began our final lunar orbits, operating the panoramic camera until the film ran out. No sense in wasting it, and who knows what it might pick up. Somewhere below us, a Soviet robot was driving around on the surface making discoveries of its own. Perhaps we would capture it on film and have a cool photo to present to the Russians.

“We’ve powered up the drugstore to receive the film when you get home,” Joe Allen joked from mission control.

“Better get a couple,” I quipped. We had a mile-long roll of film to develop.

It was time to raise our orbit a little, so the little satellite we were about to deploy could circle for a year before it was tugged down by gravity. A quick three-second burst from our engine raised our orbit by more than ten miles.

In our last hours around the moon, I received a heart-warming message. “I have a message for Al,” Joe Allen radioed from Houston, “from the King.”

“Go ahead, Joe,” I replied, curious to hear what Farouk wanted to tell me.

“The message to you is to stand by to copy your final exam grade in orbital science and observation,” Joe replied. “It’s an alpha-plus, with a subnote of: well done.”

“Tell the King thank you very much, Joe,” I responded with a grin. “I expect to see him back in Houston soon.” I was delighted that Farouk was so happy with my work.

It was time to launch our small subsatellite from the side of the service module. Launching an unmanned spacecraft from a manned spaceship around the moon had never been attempted before. I carefully aligned Endeavour, flipped a switch, and from its cradle inside the service module I could hear the satellite whipping along a curved groove in its spring-loaded release device like a bullet in a rifle barrel. By the time it spun off the end and into its own lunar orbit, the little tubular satellite was rotating fast enough to push out three whip-like arms which stabilized its wobbling spin. We watched it leave from our windows, its tiny solar panels glinting in the sunlight. Dave cried “Tally Ho!” to mission control, an old pilot’s phrase for spotting another aircraft, adding “a very pretty satellite out there.” Scientists on Earth would track the satellite for months to come, learning more about the moon’s gravity field, Earth’s magnetic field near the moon, and solar particles. The moon’s gravity would eventually drag it down to make a new crater, our mission’s final touch of the lunar surface.

I had enjoyed my six days in lunar orbit. It sounds like a hell of a long time, but there was so much to see and explore that I never grew bored. The sunlit part of the moon shifted as the days went by, so there were always new places to view. I could have happily spent a few more days there—the same feeling I get at the end of a great vacation. But it was time to go home.

I busily checked the temperatures and pressures of our main engine’s propellant tanks. If there was ever a time that I felt particularly tense or nervous on the spaceflight, this was it. With no lunar module, we were down to one engine. If it failed, I’d be looking at the lunar surface for the rest of my life, which would be as long as our oxygen lasted. In addition, without Falcon attached to the nose, Endeavour was a much lighter machine. If our engine’s control system did something wrong, I would have to react instantly, or we could be quickly rocketed in the wrong direction.

As Earth began to set on the lunar horizon and we prepared for our final pass over the lunar far side, Joe Allen wished us luck with a final nod to James Cook’s era of exploration. “Set your sails for home,” he told us. “We’re predicting good weather, a strong tailwind, and we’ll be waiting on the dock.”

“Thank you very much,” Dave replied. “We’ll see you around the corner.” Mission control would not know the success of our engine firing for sure until we emerged from behind the moon.

Then we lost radio contact with Earth for the last time. I thought back to my television interview with Fred Rogers. A child had wanted to know if I’d be scared flying to the moon. It was important to be honest. Yes, I replied, risky work can be scary.

When the engine lit, it was a real kick in the pants. I could feel the steady acceleration as it burned for over two minutes. I warily watched the gauges that told me our engine was burning smoothly and steadily, speeding us on the correct curved pathway out of lunar orbit and back to Earth.

To my relief, the burn was beautifully smooth. Soon we rounded the far side again and, as we climbed away from the moon on our new course, Dave could announce “Hello, Houston. Endeavour’s on the way home.”

We shot away from the moon at more than fifty-seven hundred miles per hour, turning the spacecraft so we could look back and use up much of our remaining film on the rapidly receding moon. “We’re almost speechless looking at the thing,” Dave told mission control. “It’s amazing—looks like we’re going straight up,” he added, commenting on our new burst of speed. “We’re leaving, there’s no doubt about that.”

It was clear from my first glimpse out of the window that the moon was shrinking. And the dramatic sun angle highlighted new features for our parting glimpses. Parts of the lunar south pole and the immense crater Tycho were visible for the first time, and I took pictures with a mixture of fascination and sadness. I’d never get to see them up close again.

“That’s a pretty good view after all those days of going around and around, isn’t it?” Dick Gordon radioed from mission control.

“Yeah, boy,” I replied, scanning the rugged terrain that bulged out in our direction. “We’re looking at new territory.” For the first time in a week, I could gaze at the entire sphere of the moon in one window. “You can see it all in one big gulp, and boy, what a gulp!” I continued to describe lava flows that we had not spotted before, until the details were too hard to make out anymore.

I fiddled with some SIM bay experiments, placed the spacecraft back into barbecue mode, then settled in for our three-day coast back to our home planet. Mission control signed off, reminding us that “our ever-watchful eye will be on you while you sleep.” Before the day was out, Dave shared a pleasant thought with Houston. “We’ve got another unanimous vote up here. That was really a great trip.”

It almost sounded like the mission was over. But as I went to sleep, I knew that tomorrow would be one of the most important days of my astronaut career. I would make the first-ever deep-space EVA.

When I woke the next morning, I first had to carry out some navigation. We had one shot to get back home, and I wanted to be on course from the beginning. While Houston kept an eye on us to make sure we didn’t stray out of a general path of certainty, I hoped to prove that it was possible to navigate to and from the moon without their help. I was aiming for a narrow sliver of horizon on a planet tens of thousands of miles away, and there was no margin for error. This far from Earth, the tiniest changes in direction could result in huge errors once we had traveled the remaining distance in our voyage.

I used my sextant and measured the angle between Earth’s horizon and my preselected stars. However, I also had to choose the right place on the horizon. Our planet is about eight thousand miles across, and the horizon is only fifty miles thick. That sounds tiny, and it looked tiny from so far away, but fifty miles was too wide for what I needed to do. I needed more accuracy.

In my training I had calibrated my eye for a specific part of the atmosphere. Between Earth’s surface and the blackness of space, the atmosphere looked like narrow bands of different colors, mostly subtle differences of reds, magentas, and blues. I had experimented in simulations on Earth to identify a thin color line I could find consistently. I looked for a particular light blue within the atmosphere when navigating, and this reduced the fifty-mile width to a much smaller path as we left the moon. It worked even better than it had in the simulators—we stayed firmly on track.

Mission control called again and jokingly congratulated me on the accurate navigation. “They’re awarding the honorary ‘Vasco da Gama Navigation Award’ for excellence in this,” Joe Allen teased, referencing the early Portuguese explorer who’d sailed from Portugal to India—and back again, which was more on my mind at that moment.

“Be advised,” Joe added, “you are leaving the sphere of lunar influence and it’s downhill from here on in.” We were still much closer to the moon than the Earth, but because our planet is so much larger, its gravity pulled on us more. We were now truly falling to earth. It meant nothing to us in the spacecraft—there was no physical sensation of movement, no outside indication of our incredible speed as we shot through the empty black void.

There was a slight sense of disconnectedness on the long journey out and back between moon and Earth. At every other time in my life, even in Earth or moon orbit, there was a sense of the ground being below me. Here, both Earth and moon were remote, faraway places. I found it really stimulating. To see the sun, Earth, and moon in sequence as our spacecraft slowly spun made me think more about the moon rotating around Earth, which in turn rotated around the sun. I’d read about this in school and knew it intellectually. However, to be out in deep space and see it firsthand made me sense it on a deeper level. The human species seemed both more and less significant now: less, because I felt dwarfed in this vast blackness; more, because I was able to see it and explore it.

It was time for the three of us to float back into our spacesuits and help each other zip up. We placed guards over the control panel switches so I wouldn’t kick them as I floated outside. I disabled some spacecraft thrusters: the last thing I needed was a thruster to fire as I floated by. We also stowed and tied down loose items in the cabin. After the work Dave and Jim had done to collect moon rocks and place them in sample containers, we didn’t want our prizes to float out of the hatch. We worked slowly and carefully through our preparations for my spacewalk, and everything went very smoothly. I was glad because we were about to do something never tried before in the program.

“You have a go for depress,” mission control told us. We slowly began to let the oxygen out of the cabin through a special valve in the hatch. Everything in the spacecraft looked the same, but I knew now that if I took off my helmet, I would die. The inside of Endeavour was soon as airless as the deep space we traveled through.

“We’re getting ready to open the hatch,” Dave reported. “Okay. Unlatch.” I depressed the safety lock that meant the hatch couldn’t be accidentally opened, always a wise precaution in space. I pumped the hatch handle to rotate the latches out of their locked position. Then, with a careful push, I swung the hatch open.

Apart from briefly floating inside Falcon days before, I hadn’t left the confines of Endeavour for eleven days. I’d last slid through this hatch on the launchpad in Florida. Now I was about to float out of it more than 196,000 miles from home, into the deep space between Earth and moon. It was a thrilling thought.

“The hatch is open,” I announced. The open, square hatchway now framed only deep blackness. I poked my head outside and carefully mounted a TV camera and a movie camera on the hatch so they could capture my spacewalk. Then, grabbing the nearest handrail, I soundlessly floated outside into the void.

I paused a moment and waited for Jim to poke his head and shoulders out of the hatchway behind me. He would stay there and keep an eye on me while I made my way down the side of the spacecraft. Other than our service module glinting in the sunlight, it looked really black out there. I looked down the length of the SIM bay. “The mapping camera is all the way out,” I reported to mission control. It was one of the pieces of equipment that had begun to fail as the flight went on, and I had suspected it could no longer retract all the way back into its housing. Sure enough, it was sticking out. This could complicate my spacewalk a little as I would have to float over it without losing my grip on the handrails. “You ready, Jim?” I asked. “I’ll work my way down.”

After eleven days in space, I was accustomed to weightlessness. Working outside turned out to be a lot simpler than I thought. With one hand on a handrail, I could turn my body with my wrist. The SIM bay was slightly to the left of the hatch, so I first needed to swing across the face of Endeavour. I let my legs float up, and then I swung around and worked my way down the side of the spacecraft, hand over hand, never using my feet. It was even easier than in the water training tank.

I floated over the stuck mapping camera, then rotated myself on the handrail, placing my feet in special restraints. I took a quick look around while Jim floated into position.

I hadn’t really had a sense of where I was until this moment. Standing upright on the side of the spacecraft, attached only by my feet and the umbilical that loosely snaked back to the spacecraft hatch, I had a fleeting sense of being deep under the ocean, in the dark, next to an enormous white whale. The sun was at a low angle behind me, so every bump on the outside of the service module cast a deep shadow. I didn’t dare look toward the sun, knowing it would be blindingly bright. In the other direction, and all around me, there was—nothing. It’s a sensation impossible to experience unless you float tens of thousands of miles from the nearest planet. This wasn’t deep, dark water, or night sky, or any other wide open space that I could comprehend. The blackness defied understanding, because it stretched away from me for billions of miles.

But there wasn’t time to ponder it too much. I had work to do. I pulled the cover off the panoramic camera, released the film cassette and tethered myself to it. It came out even easier than I expected, although it felt a little bulkier than in simulations. Keeping one hand on its handle, I used my other hand to pull myself back toward the hatch. When I came to the stuck mapping camera again I had to let go of the handle for a second to maneuver over it. But it was only for an instant as I swung my legs out wide, then I had a firm grip once again.

Jim waited for me at the hatch. “Would you like to get hold of it?” I asked with a laugh as I passed him the film. Jim tethered it inside, released the tether attaching me to it, and I was free to float back down again. It was all going so simply. If I had known that Jim, now blocking the hatch, had heart problems, I may have felt much less secure. If he’d had a heart attack at that moment, we’d all have been in danger.

But Jim was okay. While Dave stowed the panoramic camera film deeper in the cabin, I floated back down the side of the spacecraft. “Beautiful job, Al baby!” Karl Henize radioed from Earth. “Remember, there is no hurry up there at all.”

“Roger, Karl,” I replied as I grabbed the handrail again. “I’m enjoying it!”

I floated back down the SIM bay, much faster this time. I’d been asked to look at one of the panoramic camera’s sensors. It hadn’t worked well during the mission, and the engineers on Earth wondered if there was perhaps a crack or contamination in the lens. I floated over it and peered in. “There’s nothing obscuring the field of view. The glass is not cracked,” I reported. “It’s perfectly clear.” Engineers would later find that the problem with the sensor wasn’t with the lens after all, but the signal.

I also had a look at the mass spectrometer. We’d had trouble with its boom, and when I peered at it closely I could see it hadn’t completely retracted, a problem that seemed to happen only when the equipment was in shadow. It had been too cold to work correctly. I could explain exactly what the problem was, a luxury mission control rarely enjoyed with instrumentation on the outside of a spacecraft.

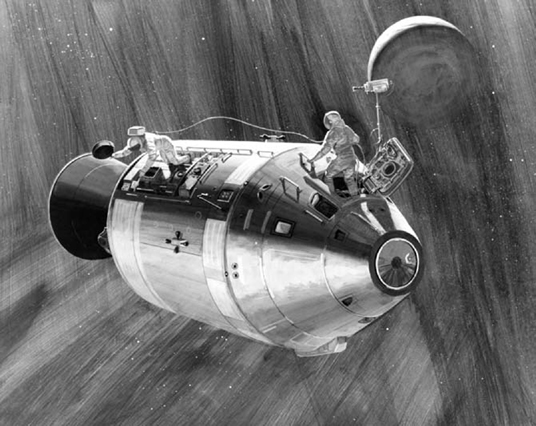

A NASA artist’s impression of my spacewalk with Jim watching from the hatch

It was time to remove the mapping camera film cassette and bring that back inside, too. This time the cover didn’t cooperate, and I had to twist and pull hard three or four times before it came away. But after that, it was simple. I pulled the mapping camera film out and floated it back over to Jim, who grabbed it and unhooked the tether from me.

As we did this, I saw one of the most amazing sights of my life. “Jim, you look absolutely fantastic against that moon back there,” I exclaimed. “That is really a most unbelievable, remarkable thing!”

Jim was perfectly framed by the enormous moon right behind him. It looked as big as the spacecraft, and was dramatically lit by the sun, emphasizing the rugged craters. I could even see myself, floating in space, reflected in Jim’s visor. It could have been the most famous photo in the space program, if I’d been allowed to take a camera out of the spacecraft.

I’d argued for carrying one, but the mission planners had worried I’d be busy enough. Now, I really wished I’d had one. Not just for the photo of Jim. I could also have shown them what was wrong with the mass spectrometer instead of just describing it. And there was something else I spotted which would have been good to document: the thrusters on the side of the service module had bubbled and burned the module surface when they fired. We’d never been able to see this before, and it wasn’t good. It hadn’t damaged anything vital that I could see, but I guessed the engineers would want this problem fixed before the next mission.

Well, if I didn’t have a camera, I could at least take a look at where I was. After all, twelve people would walk on the moon during Apollo, but only three would make a deep-space EVA. I would forever be the first, and to this day I hold the record for floating in space farther away from Earth than any other human.

I realized I had a unique viewpoint: I could see the entire moon if I looked in one direction. Turning my head, I could see the entire Earth. The view is impossible to see on Earth or on the moon. I had to be far enough away from both. In all of human history, no one had been able to see what I could just by turning my head. It was incredible.

My major tasks outside were done. It had been so simple, I was amazed. I’d practiced so much back on Earth that my spacewalk went by very fast, so fast, I couldn’t believe it was already over. When mission control asked if I had any other general comments on the SIM bay before coming back in, I took the opportunity to make a third and final float down to the mapping camera to see if I could work out why it had jammed. I did a cartwheel motion on the handrail, examining the camera from many angles. With the sun angle so low, it wasn’t easy to inspect. In the vacuum of space the shadows on the spacecraft were a deep, impenetrable black. The camera cast a dark shadow, and I couldn’t see anything jamming it in place. It was time to float back inside.

I carefully pulled the hatch closed. It swung in smoothly and latched easily.

Right away, I wished I had spent more time out there just looking around. We had plenty of time. Those film canisters with their priceless images were now safely inside the spacecraft. But I could have soaked in the scene a little more, just for myself. I would also have liked to have floated all the way down to the base of the spacecraft to examine the engine bell. But I know mission control wouldn’t have liked that.

If I couldn’t take photos outside myself—and Jim had not taken any stills of me either—I knew that at least the fuzzy TV camera and the far sharper 16mm movie camera should have picked up some spectacular images. But I was wrong. The 16mm camera, we learned later, had jammed. It had captured only one frame showing me floating away.

I teased Dave and Jim about this when we got back to Earth. You guys have hundreds of photos walking on the moon, I joked, and I only have one shot of me doing my spacewalk. And is it of my head? No. It’s a photo of my spacesuited ass. Thanks a lot!

When I returned to Earth, to make up for the lack of photos, National Geographic magazine commissioned the talented artist Pierre Mion to paint my view of Jim framed by the moon. After I described what I had seen to him, Pierre did a wonderful job capturing it, the next best thing to being there. The image was printed in the magazine. I recommend you search out a copy and look for the little image of me reflected in Jim’s helmet visor.

We gradually brought the cabin pressure back up, until it was safe to remove our spacesuits. Jim’s heart had held out just fine. And Dave was delighted with the EVA. “You’ve done good,” he exclaimed with a laugh. “You’ve made a lot of people back there very happy!”

Karl Henize soon added more praise from Houston. “The guys down here would like to send up their warmest congratulations,” he radioed. “You sure made it look easy up there.”

I brought some of the SIM bay experiments back online, this time to point them at a mysterious X-ray source in a faraway binary star system. We continued to run other experiments, such as taking ultraviolet photos out of the window. We all felt more relaxed and happier—the key parts of our mission were now completed. I still needed to navigate our spacecraft, but other than that we simply prepared to get back to Earth. We chatted about how, compared to earlier flights, lunar landing missions had much less room for error.

“This is sort of an all-or-nothing kind of operation, you know?” Dave remarked to me, when Houston wasn’t listening in. “It really is,” I agreed. “All your eggs in one basket, boy. I got to thinking about that after you guys left for your descent. Once you start that descent, man, that’s it … It’s all hanging out from there on.”

With most of the danger now over, we could ponder the amazing events of the last few days. “I wish I would have tried running alongside the rover at the same pace,” Jim chimed in. “It would’ve been neat to do a few things like that.”

“Well, I’ll tell you, I’m sure glad we got rid of that clothesline operation,” I added, thinking again of the original plan to bring in the film cassettes during my spacewalk. I’d loved every minute of my EVA. “It’s really a ball when you get all suited up, get cooled off, and get the hatch open.”

The television camera image of me floating in the deep blackness of space

I thought some more about the moon. It had been an incredible place to visit and a wonderful mystery to try and unlock, but it was scarred and dead. And what can the living truly learn from the dead? Earth, growing a little larger in our windows, looked beautiful and full of life. It was time to sleep once again, with a smile on my face. I was going home.

When we awoke for the twelfth day of the mission, we still had more than one hundred and fifty thousand miles to go before we’d reach Earth. Even though we sped along at more than four thousand feet per second, we had another day and a half of travel ahead of us. We were truly a tiny sliver of metal crossing this huge, dark void.

Despite the distance, we never felt alone. Houston continued to send us new changes for the flight plan, along with updated instructions for our science experiments. They reported that the weather looked good for our splashdown zone; I wouldn’t have to redirect our course. Dave stayed relaxed and happy. “Yesterday, we finally got to catch our breath,” he told mission control. “The hours are long, but the accommodations are palatial!”

Karl Henize radioed an unexpected update on one of the SIM bay experiments from its chief scientist. “On the gamma-ray experiment, Dr. Arnold reports that Al Worden probably performed the first recorded repair of a scientific instrument in space, because earlier in that day he’d begun to experience some problem with excess noise in the gamma-ray experiment. And when Al went out in the EVA—we don’t know what happened there—but at the end of the EVA, the gamma ray cleared up and has been doing beautifully ever since. You must have given it a pretty good kick there, Al.”

I didn’t recall accidentally kicking it, but I was glad to hear it worked again. “Not only is he a plumber, he’s an electrician as well!” Dave quipped.

Houston also reported with delight that a special mirrored device left on the lunar surface by Dave and Jim was bouncing laser beams back to Earth perfectly. The TV camera left at Hadley plain was less successful. It had been panning around the landing site when it suddenly stopped working. “Would you like us to go back up and check it for you?” Dave asked with a grin.

“Knew you were going to ask!” Joe Allen laughed in response.

Joe read us the morning news. “The government reports today the latest figures in the nation’s unemployment problem, and one private economist predicts the jobless rates probably will show still another rise.” I thought briefly about the Apollo program and the layoffs of all the amazing workers we’d collaborated with. There were only two more missions ready to go to the moon after ours. The moon landings would soon be over. A lot of people would lose their jobs, and many astronauts would sit around with nothing to fly.

I still wasn’t completely sure this would be my only spaceflight. I felt much more certain that it would be my only flight to the moon. Perhaps, in hindsight, I should have spent more time in those last days enjoying the view and weightlessness, as I would never have them again. But I really only thought about the things I needed to do to ensure we returned safely home.

“Al, the way people talk down here, they’re going to give you a medal,” Karl Henize radioed, impressed by my continuing navigational accuracy.

“Congratulations, Al, you’ve just been voted to receive a second Vasco da Gama award,” Bob Parker on our support crew added. Thanks, guys, I thought to myself. That meant a lot to hear.

We had time to give a press conference in space, answering questions submitted by reporters. I enjoyed the conversation because it made us feel even closer to home. I was asked about the highlights of the flight so far. One, I said, was the engine burn into lunar orbit, when I saw the moon up close for the first time. The other was the successful burn out of lunar orbit, meaning we’d come home. That about summed it up—amazing exploration and staying alive.

After some other discussion about Apollo 15 “already being described as one of the great events in the history of science”—that was nice—they asked me about my spacewalk the day before.

“As far as what I felt like when I went out there,” I explained, “it was sort of like walking on stage at your high school dinner dance or something. We opened the hatch and it was pitch black, and as soon as we got out, the sun was beating down on everything, and it looked like a very large floodlight on a stage. And then putting the TV camera out on the door just added a little bit more to that sort of unreal feeling that it was time to get out on the stage and do something.”

“If you could see the size of the film magazines that Al brought in yesterday from those cameras,” Dave added, “you’d see that we have indeed at least a great deal of data on film alone.”

“Hopefully, we’ve added to our store of information about the moon and about ourselves,” I concluded, “greater than the capital that was spent on the flight itself.”

Before we turned the camera off, I flashed a quick victory sign at the viewers, as I had done on the way to the launchpad. We would be successful on the flight, much like going into combat, and we were sure of winning. Now we had succeeded in our mission, I made the gesture for a second reason—as a peace symbol. When looking at Earth as a whole planet, that seemed appropriate.

We spent much of the day stowing all the items in Endeavour’s cabin. The spacecraft’s center of gravity could not be off balance during our carefully planned plunge back through Earth’s atmosphere the next day. We handled the moon rock sample containers with particular care, until the space beneath our couches was jammed with carefully arranged white bags. It was time to settle in for my last sleep in space.