My subject is divination, and I had better give a hint as to what it means. The Oxford English Dictionary, I’m afraid, is unhelpful, concerning itself largely with the primary sense (prophecy and augury) and coming close to me only in treating what it calls the “weaker sense”—“guessing by happy instinct or unusual insight; successful conjecture.” Now that everybody finds literary theory so much more interesting than literature, we must expect a certain amount of imperialist rapine. A recent issue of Critical Inquiry has an article on information-processing in reading poetry, and deals, it claims, with “variant readings” of a poem, always an absorbing subject. But I soon saw that “variant readings” now means not what it used to mean, namely variae lectiones, conflicts of textual testimony, but rather the different ways in which various people read the same poem. My complaint is not that this matter is not worth the writer’s time, or mine; merely that a new interest, supported by all the modern armaments of phenomenology, Gestalt psychology, information theory, and so forth, has usurped an expression that has had for centuries a perfectly plain and very different meaning. Let us, while we may, use the old sense of varia lectio; it reminds us of an old, yet still current, sense of the word “divination.” It may be weaker, but it is strong enough for me. For divination, divinatio, is a power traditionally required by those who wish to distinguish between variant readings, and to purge corrupt texts.

I shall add at once that nobody can suppose divination is merely inspired guesswork. Freedom to divine, in this sense, has been restricted since the Renaissance, and especially since the early eighteenth century, by the advance of what might be called science. Philology has always claimed to be so called, and especially in the nineteenth century aspired to the rigor of even more fashionable sciences. Indeed, in its modern forms it still does so. And the truth is, that much knowledge has been progressively acquired. How texts are transmitted through time, what are the habits and failings of scribes and compositors, the paradoxes of history which make it possible that the earliest is not the best manuscript or edition—all this lore is now quite well understood. The liberty to divine is reduced by this understanding of the possibilities, and even geniuses are no longer allowed the freedom enjoyed by, say, the great Bentley.

All the same, it would be wrong to think of science as the enemy of divination. All it does is to define its limits. I doubt if one could find a Shakespearian who would deny the proposition that Charlton Hinman’s vast book on the printing of the First Folio1 is one of the essential contributions to the study of Shakespeare’s text; yet as far as I can tell Hinman never so much as proposed an emendation. What he did was to define more precisely than had been thought possible where and how the text is likely to have gone wrong. The way of the editor is by this means made clearer and narrower. But he will still have to divine.

Some great diviners like to affirm that divination is a gift you are born with, that it cannot be taught. George Steiner recently quoted A. E. Housman’s famous words to this effect.2 I doubt if they are wholly right, but they’re not wholly wrong, either; history supports them, up to a point. For, as L. D. Reynolds and N. G. Wilson observe in their book Scribes and Scholars,3 “while general principles are of great use, specific problems have a habit of being sui generis.” And we need to remember also that some, perhaps most, of the most impressive emendations made in texts of every sort were provided by scholars who had never heard of stemmatics, or of Hinman’s ingenious optical machine—who were ignorant of principles and information now available to everybody—what went on in scriptoria, what were the habits of Elizabethan compositors, and lots of other things.

However, we must not suppose that divination is something only textual scholars do. In the early years of the last century Friedrich Schleiermacher, generally remembered as the founder of modern hermeneutics—the science of understanding texts—took over the term divinatio for something rather different. Schleiermacher needed a word for a moment of intuition which was necessary to his theory, and also, probably, to any commonsense view of what it is we accomplish when we interpret a text. We understand a whole by means of its parts, and the parts by means of the whole. But this “circle” seems to imply that we can understand nothing—the whole is made up of parts we cannot understand until it exists, and we cannot see the whole without understanding the parts. Something, therefore, must happen, some intuition by which we break out of this situation—a leap, a divination, he called it, whereby we are enabled to understand both part and whole.

Much has happened since Schleiermacher’s day. In our own time we hear a lot about the “reader’s share” in the production of sense. For every act of reading calls for some (perhaps minute) act of divination. We may content ourselves with obeying clear suggestions and indications in the text—as, for example, to setting, character, what we ought to be thinking about the action described or enacted. Every competent reader can do that much, and there is in consequence what is called an “intersubjective consensus” about the meaning of the text. But we may have to do rather more; there are works, especially modern books, which may frustrate such responses, or at least suggest a need for going beyond them. And it is quite usual to attach more value to such complex works, and to feel that our relating of part to part and parts to whole is the only means by which anything like the sense of the whole can be achieved. In other words, our power of divination is necessary to the whole operation—without it there will be no sense, or not enough.

It follows, I think, that we can distinguish between normal and abnormal divinations. The first kind we refer to the “inter-subjective consensus”—we expect the agreement, without fuss, of competent, similarly educated people. Then there is the second kind, which we also submit to our peers. But this time they will not simply nod agreement, but either reject it as preposterous, or hail it as brilliantly unexpected, a feat of genius. For although there is no guarantee whatever that the institutional consensus will always be right, it knows the difference between the valuable normal and the abnormally valuable. Though it will condemn divinations that run counter to its own intuition, the institution will tend to admire most those divinations which cannot be made by the mechanical application of learnable rules. Divination, in other words, still has the respect of the bosses.

What I have been doing so far is this: I have been suggesting that divination as the whole concept applied to the correction of texts is a special form of a more general art or skill, which we all employ, at one level or another, in the interpretation of poems and novels. The difference is merely one of degree; for in all cases divination requires, in its treatment of the part, an intuition of the whole. It would be possible here to introduce a related topic of much interest and difficulty: the relation between the reader’s act of divination and the process by which authors compose the texts in the first place. The poet’s drafts may show him preferring one word to another, even sometimes substituting a word of which the sense is the opposite of the original, as better in relation to the yet undetermined whole of the poem. The novelist, who may or may not have a Jamesian scenario, but who will have some probably indistinct intuition of the whole as he labors through the parts, can be found making the most drastic changes to the part as that intuition fluctuates, or discovers itself. But that would be another essay, and a harder one as well. I shall stick to lower forms of divination, using examples.

The devil answers even in engines.

The first example, as a matter of fact, is a sort of warning. A word once favored among critics was “sagacity.” Dr. Johnson had a great respect for “critical sagacity,” and we may take it as representing, under another guise, the power to make acceptable divination. Johnson admired one emendation made by Thomas Hanmer in the text of Shakespeare so much that he said it almost set “the critic on the level of the author.” One day he gave Boswell a test. He pointed to a paragraph in a book by Sir George Mackenzie, and asked Boswell whether he could spot what was wrong with it. “I hit it at once,” says Boswell. “It stands that the devil answers even in engines. I corrected it to ‘ever in enigmas.’ ‘Sir,’ said he, ‘you’re a good critic. This would have been a great thing to do in the text of an ancient author.’” But James Thorpe, from whose learned and amusing book4 I borrow the example, is inclined to think that Boswell is wrong, at any rate about engines, which can be held to make perfectly good sense. It can mean “snares, devices, tricks.” “If so: poor over-clever Boswell; alas, poor over-knowing Johnson,” says Mr. Thorpe. To be truly sagacious you have to know when divination is not called for.

Diviners had best be prepared to be called over-clever, over-knowing. In the days of Richard Bentley, the “modern” skill in emending ancient texts met with a lot of opposition of this nature from people who favored this “ancient” side of the quarrel. Bentley’s self-assurance was assaulted by Swift and ridiculed by Pope. The notes to the Dunciad are full of such mockery.

lo! a Sage appears

By his broad shoulders known, and length of ears

says the text, and the notes call “ears” a sophisticated (that is, a corrupt) reading. “I have always stumbled at it,” says the annotator Scriblerus, “and wonder’d how an error so manifest could escape such accurate persons as the critics being ridiculed. A very little Sagacity … will restore to us the true sense of the Poet, thus,

By his broad shoulders known, and length of years.

See how easy a change! of one single letter! That Mr. Settle [the Sage] was old is most certain.”5 Such unkind responses to divination not only remind us of the risk it involves, but also cause us to reflect that the task of the diviner may often be very difficult. Indeed there are problems for the solution of which it is safe to assert that nobody has ever had, or will ever have, sufficient sagacity. All one can do is to award them what is known as a crux desperationis, a cross of despair, a sign that they are beyond human ingenuity.

(A) a nellthu night more

(B) a nelthu night Moore

(C) come on bee true

(D) come on

My second example offers a sample pair of hopeless cases. (A) is from the 1608 Quarto of King Lear, (B) from the second Quarto of 1619. It is obvious that nobody could have made head or tail of them, had not the true reading survived in the corrected state of QI and in the Folio text of 1623: “He met the night-mare.” (C) and (D) come from the same scene (III.iv), the first from the uncorrected QI, the second from the corrected QI. So if Heminge and Condell hadn’t put together the First Folio in 1623 we should not have known that Lear, tearing off his clothes in the storm, says “Come, unbutton heere.” He is raving, and might have said either or neither of the things preserved in the Quarto; and no diviner could have done anything about it.

Then the stars hang like lamps from the immense vault. The distance between the vault and them is as nothing to the distance behind them …

However, the diviner’s problem may arise from difficulties less obvious than those, for example when he has first to divine that, contrary to appearances, there is a need for his services. The third passage is from the beautifully composed opening chapter of E. M. Forster’s A Passage to India. Let me play Johnson to your Boswell: what’s wrong with it? Well—isn’t the distance between the vault and the stars the same thing as the distance behind the stars? Could it be that a typist or compositor has accidentally repeated the word vault instead of what the author wrote? (This is called dittography by the experts.) Yet the fact is that between 1924 and 1978 nobody noticed there was anything wrong. Now we know that the manuscript reads not the second vault but earth; and the typescript also survives, so we know it was the typist who made the mistake, and that Forster set a good precedent for all who study him by not noticing it for the remaining half-century of his life. Perhaps some genius a thousand years hence might have been smart enough to see that somebody had gone wrong, and bold enough to risk the conjecture earth. Perhaps not. Anyway, he was forestalled. The moral may be: don’t burn your manuscripts, diviners can’t be trusted in every case.

She was praising God without attributes—thus did she apprehend Him. Others praised Him without attributes, seeing Him in this or that organ of the body or manifestation of the sky.

The fourth extract is also from A Passage to India. Boswell should find this easier; obviously the second without should be with. Forster’s editor, Oliver Stallybrass, who loved his job, once went through my copy checking conjectures against the manuscript, and this one was right. But although the balance of the sentences (“Some … Others”) to say nothing of the fact that the second without attributes is followed by a catalogue of attributes, makes it obvious to the meanest diviner that something has gone wrong, the right reading appeared in no edition before Stallybrass’s, in 1978, more than fifty years late.

We must conclude from this that attentiveness is necessary to divination; reading novels, we are all too ready to skip over interruptions in the flow of words, and in so doing miss many opportunities; for the texts of many standard novelists are much worse than Forster’s. Our laziness has important implications; if we miss such manifest errors, we may also miss less manifest subtleties. By under-reading we fail to divine the larger sense of a novel. But I shall come a little later to that kind of divination.

In the offing the sea and the sky were welded together without a joint, and in the luminous space the tanned sails of the barges drifted up with the tide and seemed to stand still in red clusters of canvas sharply peaked, with gleams of vanished spirits.

Here is one more instance of a famous text with an obvious corruption, from the opening paragraph of Heart of Darkness. There is something odd about vanished spirits; everything else has to do with the shapes and colors of the natural world. You can argue that Conrad, who was anyway rather keen on ghosts and spirits, is preparing us for the talk about the London river centuries ago, when the Romans used it, and you can supply other explanations of that sort—indeed there are ingenious explanations on record. If you are more skeptical you may look at other versions of the text, and find varnished spirits, which doesn’t help much. What Conrad himself wrote was varnished sprits; I have only to say it for you to think it obvious. Yet if some Boswell had guessed it, that would, as Johnson said, have been something; and there would have been no doubt that he was right. But the answer was got by looking back to the first edition. The other readings are progressively corrupt, as the texts of all novels are, for the next edition repeats the mistakes of the previous one, and adds more.

Heart of Darkness is more or less intensively studied in the classroom by hundreds of experts and thousands of students every year. Unless they use the Signet edition, they all meet this corrupt reading instantly. (The Signet is the only popular text I can lay my hands on that has it right. The Oxford Anthology, I regret to say, has it wrong.) Nobody, so far as I knew, ever divined the true reading. This tells us among other things that there may be something wrong with the way we focus our attention on texts. Of course it doesn’t amount to much: “one single letter,” as Scriblerus remarked, and vanished replaced varnished; then somebody thought vanished sprits looked queer, and added another single letter to sprits.

You are a Counsellor if you can

command these elements to silence,

and worke the peace of the present, wee

will not hand a rope more …

Sometimes it seems that we will do almost anything rather than get the right answer. The sixth extract is from the opening scene of The Tempest. The Boatswain wants to get rid of the courtiers, who are getting in the way of the sailors as they cope with the storm. “The peace of the present” is an unusual expression, but it might just pass—“bring the present moment into a peaceful state,” or something of that kind. Still, it is odd; and if you read presence (supposing that Shakespeare wrote presenc and the scribe mistook the c for a t) you have a known expression. It means the area occupied by the king and his court; within it peace is kept or preserved or “worked” by his officers. This conjecture, by the late J. C. Maxwell, seemed right to me, and I put it in the text of my edition of the play,6 where it has been on view for over thirty years without attracting the slightest notice. It makes sense; the explanation in terms of graphic error came after the divination, as Housman says it should; but the world remains content with present. There are some interesting implications. First of all, there is in all guardians of sacred texts a profound conservatism. Erasmus edited the Greek New Testament, not very well; in fact by later standards very badly. But it became the received text, and for three hundred years scholars who knew perfectly well that it had many obvious mistakes did not dare to change it, and smuggled the right readings into the footnotes. So with Shakespeare, whose texts are riddled with error. In the eighteenth century there was much liberty; but in spite of an occasional plea for boldness, it is now normal to give sage approval to the claim that a text is very conservative. The diviner is not a popular person; he is constrained by professional skepticism and by our veneration for the received text (as if the merits of the Bible and Shakespeare rubbed off onto scribes and printers) as much as he is by the formidable growth of editorial “science.”

Oh Sunne, thy uprise shall I see no more,

Fortune and Anthony part heere, even heere

Do we shake hands? All come to this? The hearts

That pannelled me at heels, to whom I gave

Their wishes do dis-Candie, melt their sweets

On blossoming Caesar: and this pine is barkt

That over-top’d them all.

That is why I have to look back to the eighteenth century for an example of divinatory genius at work on Shakespeare. Look at the extract above, which is from the original text of Antony and Cleopatra. Antony is nearing the end; he has lost, his followers have left him. Something is wrong, though, and it must be the word pannelled. Thomas Hanmer, in 1744, said it should be spanielled; and we have most of us accepted this (or spannelled) ever since. It is one of the finest emendations in the whole text of Shakespeare and one of the most certain—it is indeed the one commended by Dr. Johnson, as quoted earlier in this essay—though Hanmer didn’t know the first thing about Shakespearian bibliography. If we ask ourselves why it is so admirable we shall have to start using words like intuition or divination. Another matter of which Hanmer probably had no conscious knowledge, though it is now well known, is Shakespeare’s tendency to associate dogs, melting candy, and flattery. Of course he must in a sense have known about it, to see what was needed in place of pannelled was a doggy sort of word; it also had to be a verb in the past tense.

The importance of this point is that such divinations depend on knowledge (of course you can have the knowledge without the power to divine). Hanmer’s familiarity with the whole body of Shakespeare’s work gave him a place to jump from. He would not be alarmed that if his conjecture gained acceptance we should have to admit that Shakespeare makes hearts turn into dogs, then melt (discandy—a word used, for example, of ice melting in a brook or a lake); that the intransitive discandy generates the transitive melt and the noun sweets; that melt becomes melt on, with its strange suggestion of the erstwhile cold hearts dropping slobbered sweetmeats on a tree (dogs and trees go together) but a tree called Caesar, which is in turn contrasted with a less lucky though originally more upstanding and attractive tree called Antony. Even barkt—referring to the manner in which this tree was spoilt—reminds us of the dogs. Hanmer must have known this strange piece of language was perfectly Shakespearian; he knew the manner of his poet.

Also, of course, he knew Antony and Cleopatra, at that moment, with the peculiar intimacy of an editor. A little earlier in the play there is a scene in which Antony, smarting under defeat, is enraged to find Cleopatra treating a messenger from Caesar with what he thinks to be rather more than due civility. He who had, at the outset, dismissed with magnanimous impatience the superstitious notion that a messenger should suffer because he bears bad news, now has this messenger whipped, rather in the style of Cleopatra herself. He then turns on Cleopatra in a fury of disgust; then there’s a sort of detumescence of rage, while Cleopatra waits patiently for him to finish. (“Have you done yet?”) His reproaches grow more pathetic, and there follows this remarkable dialogue:

Antony: Cold-hearted toward me?

Cleopatra: Ah (Deere) if I be so,

From my cold heart let Heaven ingender haile,

And poyson it in the sourse, and the first stone

Drop in my necke: as it determines so

Dissolve my life, the next Caesarian smite,

Till by degrees the memory of my wombe,

Together with my brave Egyptians all,

By the discandering of this pelleted storme,

Lye gravelesse, till the Flies and Gnats of Nyle

Have buried them for prey.

Cleopatra speaks in a very elaborate figure of which the basis is Antony’s word cold-hearted. Let her heart be thought cold; let it also be thought poisoned, so that the heart’s hail will be lethal when it melts. Let these deadly hailstones kill first her; then her son; then all her posterity (“the memory of my womb”), until all the Egyptians are dead and consumed by the insects of the Nile, “melted” by them. We cannot help noticing all the synonyms for “melt”: determine, dissolve, discandy. There is a contrast between Egyptian heat and the supposed unnatural cold of Cleopatra’s heart, with the words for rapid melting mediating between them in such a way as to enforce the absurdity of the whole hypothesis (“If I be so …”). The play has made us familiar with the notions of Cleopatra’s fecundity and sexual warmth, and related the same qualities in the Nile. This great lover cannot have a cold heart; coldness belongs to Rome. The Nile floods annually, and melts its banks; and when Antony says, “Let Rome in Tiber melt!” he is invoking the impossible for merely rhetorical purposes.

I couldn’t help making a few of the many possible comments on this wonderful passage; but my real purpose is to draw attention to its connections with Hanmer’s emendation. For Antony’s “cold-hearted” here develops into very elaborate figures of melting, and the word discandy is used among others. The cold hearts and the melting pass magically over into the later speech, this time attended by a dog. Noting that the melting cold hearts seemed for some reason to be at Antony’s heels, Hanmer put the spaniel in. This part called for a very active knowledge of the whole of the play, and perhaps of the greater whole, all the plays.

After all that we are in a better position, I hope, to see how the addition of “a single letter” may truly be called an extraordinary act of interpretation, and how it calls for knowledge, knowledge which must be drawn from a greater whole yet bear down with all its weight on the smallest part, a word or a phrase. I will now try, with the aid of the eighth extract, to drive home the point that the rightness or wrongness of a particular reading may be a matter of enormous consequence; and that a preference for one reading over another may inescapably involve great decisions about the whole text in which the crux occurs. Divining is often a matter of choosing, as it is in this brief sentence from St. Mark’s Gospel.

(i) Egō eimi

(ii) Su eipas hoti egō eimi

We have here two versions of the words spoken by Jesus at the Sanhedrin trial, when the Priest asks him, “Are you the Christ, the son of the Blessed?” The first means “I am,” and the second, “Thou hast said that I am.” The first is positive, the second is noncommittal. The Jesus of Mark is nowhere else positive in his reply to similar questions, and only a short time afterwards declines to make a straight answer to Pilate when he asks, “Are you the king of the Jews?” Su legeis, says Jesus, which amounts to the same thing as su eipas. And such a reply would in this case be much closer to the run of the reader’s expectations; for Jesus, in Mark’s Gospel, has consistently refused to make public any messianic claim. Which reading is the right one?

Now it often happens that editors of the New Testament have to choose between a shorter and a longer version of the same passage. Has something dropped out of one version, or has something been inserted in the other? Long experience has evolved a rule: brevior lectio potior, the shorter reading is the stronger; all else being equal, scribes are more likely to leave things out than put things in. On the other hand, texts could be altered for doctrinal reasons; and scribes, looking at other manuscripts than the ones they are copying, sometimes reintroduce errors previously corrected. Also, copying Mark, they may alter him to conform to Matthew, who was thought to be more authoritative. Anyway, there is no rule of thumb strong enough to enforce the shorter version. We have to consider many other matters, some of them of very great importance.

For example: if the shorter version is right, we have to allow that its effect is to confound rather than comply with our expectations. Is Mark the kind of text in which the unexpected ought to be expected? In other words, what kind of book is it? Mark inserts into his account of the Sanhedrin trial the story of Peter in the courtyard denying Jesus. Peter was the man who first named Jesus as the Messiah, and here he is denying him at the very moment when for the first time Jesus himself is making the claim. If we read it that way we are virtually saying that this is a text so subtle that we can read none of it without expectations of similar subtlety. Our reading of the whole is profoundly affected. Matthew, whether he had the choice or not, used the longer version; the problem does not arise in that Gospel, which is not concerned with what is called “the Messianic secret.” We have to choose—and not between these two different versions merely, but between two different books.

The difference between homoousia and homoiousia, “of the same substance” and “of like substance,” divided the fourth-century church; one iota; “but a single letter,” as Scriblerus remarked. The choice involves a whole theology, the pressure of a whole institution rejecting heresy. Christians who declare every Sunday that they believe in Jesus Christ, being of one substance with the Father, do so because of a learned controversy sixteen hundred years ago. A single letter can make a difference.

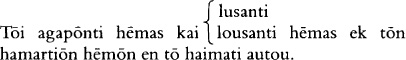

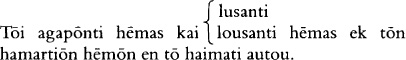

That is why I included the ninth extract, another curious instance of a choice, this time purely editorial, that has had endless repercussions upon people’s behavior and beliefs. It is from Revelation 1:5, and it means either (a) “unto him who loved us and freed us from our sin in his own blood,” or (b) “unto him who loved us and washed us from our sin in his own blood.” There are defenses available for the second version, which is the one preferred in the King James Bible and the Vulgate (lavit). Allusions to regeneration by washing are common enough in the Jewish Bible, and so, of course, are blood sacrifices; but the idea of washing in blood is not. All the evangelical tropes about being washed in the blood of the Lamb depend largely on the reading “washed.” However, lusanti, loosing or freeing, is now almost universally preferred, not only, I think, because it is the reading of the better manuscripts, but also because the washing in blood is un-Jewish and un-Greek. Thus a whole strain of evangelical imagery may depend on a scribal lapse; those who preferred lousanti divined wrong, though with interesting results.

Let us return for a moment to Mark. We have there, I think, a clear demonstration that when we attend to a minute particular of interpretation, we must do so with a lively sense of the whole text in which it occurs. The consequences of our choice may not always be so momentous, of course. And here I want to introduce a new notion, namely that it may sometimes be necessary to good divination that the practitioner should decide to minimize the relation between the part and the whole.

Whose yonder,

That doe’s appear as he were Flead? Oh Gods,

He has the stamp of Martius, and I have

Before time seen him thus.

Look at the tenth extract, which is from the first act of Coriolanus. There is nothing wrong with the text, so far as I know—which gives us another new notion, namely that divination is not merely a matter of correcting texts. In the swirl of battle Cominius has some difficulty in recognizing Coriolanus, or rather Caius Martius, as he emerges from the enemy city; he is wounded and covered in blood. He appears “as he were flayed … He has the stamp of Martius.” Is Cominius merely recognizing Martius at last, or is he also saying that the hero looks like Marsyas? Marsyas was a satyr who stole a divine flute, challenged Apollo to a musical contest, lost, and was flayed alive. Though only a satyr, he tried to behave like a god. Coriolanus is sometimes thought of as a beast-god, his conduct depending upon a particularly bleak form of presumption; he behaves toward them as if he were “a God, to punish; not a man of their infirmity.” “He wants nothing of a God but eternity and a heaven to throne in.” Shall we, having divined the presence of Marsyas in Martius, collect all the figures which speak of Coriolanus as a beast, remember that he tried to behave like a god, and announce that we have discovered some previously unnoticed key theme of the play? I think not. Marsyas, in my opinion, is present in the text; but only as a momentary glimmer. Good divination stops there; it recognizes a necessary constraint. Bad divination drives out good, which is why Richard Levin’s amusing book New Readings versus Old Plays,7 which concerns itself mostly with unconstrained divinations, has an excuse for being so wrong about the art of interpretation. It is true that people are always looking for new thematic keys to very well known plays, and that they often behave foolishly; but it does not follow that they are wrong to look. What calls for discussion (not here, not now) is the nature of the constraints. Meanwhile it is enough to say that this tiny part of Coriolanus seems to have no extensive relationship with the whole, and testifies simply to the extraordinary intellectual vivacity and freedom of association—the peripheral vision, as it were—that make the late verse of Shakespeare so inexhaustible a source of surprise.

We are now no longer talking about divination as a branch of emendation; so it is important to emphasize not only that there continue to be constraints, just as there are in emendation, but that the existence of constraints should not be misunderstood as a virtual ban on new interpretations of old texts.

“What a strange memory it would have been for one. Those deserted grounds, that empty hall, that impersonal, voluble voice, and—nobody, nothing, not a soul.”

The memory would have been unique and harmless. But she was not a girl to run away from an intimidating impression of solitude and mystery. “No, I did not run away,” she said. “I stayed where I was—and I did see a soul. Such a strange soul.”

I shall try to illustrate this point from the last of the extracts. It is quite long because I had to get in the two expressions “not a soul” and “I did see a soul.” The source is Conrad’s Under Western Eyes; Natalia Haldin is telling the narrator what happened when she visited Peter Ivanovitch, the great anarchist revolutionary, in his villa at Geneva. She stood around in a dusty hall, listening to the great man’s voice in another room; and she might have left without seeing anyone, without seeing a soul. However, the dame de compagnie, the oppressed Tekla, turned up, so she did see a soul. It would be possible to say that Conrad’s control of English idiom was never perfect (there are undoubtedly unidiomatic expressions in this as in the other novels), and that he wrongly supposed that if you can say in English “I didn’t see a soul” you can also say “I saw a soul.” This would be a way, in effect, of writing the awkward expression out of the text. But to my mind that is an illicit act; it is conceivable that a native English speaker would have intuitively avoided this locution, but it is fortunate for us that Conrad did not feel himself disqualified from writing in English because he was Polish. Nor do we resent the other forms of alienness his misfortune of birth enabled him to import into our fiction.

The word soul (with a great many variants such as “specter,” “phantom,” “spirit,” “ghoul”) occurs many dozens of times in Conrad’s novel, very often with an unidiomatic quality which serves to draw attention to it. It is, in fact, a characteristic of many long passages of the book, especially in dialogue (we must remember that it is mostly Russians who are doing the talking, Eastern behavior under Western eyes), that it takes a considerable effort of specialized attention on the part of the reader not to see and hear the language employed as extremely odd. Conrad, who wanted to sell his books, was always willing to cater to the kind of reader who has been brainwashed into the right kind of narrowed attentiveness, but he wanted to do other things as well, and a good reader will certainly divine, particularly at such moments as the one I am discussing, that several apparently incompatible things are going on at once: that the word soul is here overdetermined, belonging not merely to a colloquial dialogue but also to a “string” or plot of soul references that only very occasionally appears relevant to the simple action of the piece, and in fact constitutes an occult plot of its own. In cases like this the best emblem of the diviner is the third ear of the psychoanalyst; if Conrad is committing a parapraxis when he says “I did see a soul,” then that slip is of high analytical importance. And it is worth adding that given the kind of book one is reading, a book in which some measure of divinatory activity on the part of the reader is actively solicited (a good book, in our normal view of the matter), all occult relevances count; the question of intention does not arise.

I am now talking about divination on a rather larger scale. There are constraints upon it, certainly; but one must not be deterred by the skepticism, sometimes the ignorant contempt, of one’s peers. On the other hand, there is a difference, which the diviner himself must judge, between Shakespeare’s Marsyas and Conrad’s “soul.” In simpler cases one may depend more on a professional consensus. I should add that there is great satisfaction to be had from solving the sort of problem most unprejudiced people can see to be a problem, and to offer a solution that can command assent straightforwardly, as a matter of evidence. If I may be autobiographical for a second, I got as much pleasure out of explaining the presence of the chickens in The House of Seven Gables as from any more high-flown divinatory attempt;8 the explanation had the merit of being falsifiable; it involves a leap of some kind, but a leap anybody can take, then check whether he lands in the same place. Of course he had better not do it in ignorance; but then, as I have argued, no divinatory leap can really be taken in ignorance, however inspired, any more than it can be taken by somebody who has devoted all his study to the theory of leaping.

Intuition, that is, needs support from knowledge, whether we are editing a text or simply reading a novel. We need it even when we are reading undemanding books. We are required to do something, our share, even if that share is deliberately kept to a minimum. Coding operations are called for, even as they are in ordinary conversation. More difficult books reduce their audience by calling for a degree of competence higher than that. Some books we are inclined to think of as great very often make enormous demands, and may also contain fewer indications as to how they are to be read. Such books call forth interpretations which go beyond the consensus; they will probably include that consensus and then vary according to the predispositions and perspectives of the individual interpreter, who will nevertheless hope to have them accepted, though there is a high risk that they will be dismissed as counter-intuitive. When we are reading these great books with a proper regard for their complexity, with a sense that we, like their authors, are exploring labyrinths of interpretative possibility, we are diviners (good and bad) just as certainly as Bentley or Housman. Housman once remarked that if a manuscript readjust o he would have no hesitation in reading Constantinopolitanus if he divined that to be the true reading;9 I think we ought to take similar risks, though remembering that Housman really did know a great deal, and so must we.

We may well believe, then, that there is some continuity between the skills of the old divinatio and those of modern reading. Schleiermacher was quite right to borrow the expression for a different sort of interpretation. If you look once more at the second extract, you will have once more a sense of interpretative chastening. No two people could come up with the same answer, or if they did they would both be wrong. There are, it is conceivable, texts which similarly defy the reader of longer discourses; they would be what Roland Barthes calls scriptible texts, quite illisible, a sort of aconsensual utopia. In other cases an editor makes a reasoned choice, and we can do that also, appealing to the institutional consensus of comparably qualified persons. In still others, one may make a sensible conjecture (which might get us back from vanished spirits to varnished sprits). In others we need to be peculiarly attentive before we see that divination is called for anyway, as in the first Forster piece, and this is commonly our position when reading novels, which have a traditional duty to be clear and explicit. For all the operations I have touched upon in the editorial activity are paralleled on a grosser scale in the reading of long texts. Interpretation in that large sense still calls for the kind of skill and courage we associate with a Housman.

For, finally, there is something all we diviners ought to remember. Long after Hermes began the affair, long after Schleiermacher, there was a revolution in the analysis of long texts and in the interpretation of narrative; we correctly associate with it the name of Freud. Since his day we have learned to attend (to screw ourselves up into the posture of attending) not only to what is explicitly stated and conveniently coded, but to the condensations and displacements, the puns and parapraxes, to Shakespeare’s Marsyas and Conrad’s “soul.” In fact it seems we are taking our time about learning the lesson; we are rather slow to pursue occulted senses, evidences of what is not immediately accessible. It is the mark of what I call a classic text that it will provide such evidence; if it were not so the action of time and the accumulation of interpretations would exhaust it or make it redundant. When we admit that something more remains to be interpreted we are in fact calling for divination. It may be very refined, it may be very silly, and in either case it will probably be rejected by other interested parties. But it has to continue. In a sense the whole future depends upon it.

That, in short, is our justification. Our kind of divination, like the older kind, contributes to the sense and the value of the inheritance. The great scholars, sure of their inspiration and often full of vanity, liked to say the gift was innate; whether it is or not, nobody will claim that it can be effective without learning, without competence, without a knowledge of books and methods that can be acquired by labor. Without the science there can be no divination; without the divination the science is tedious. So here is my last word: as to divination, see first that you are born with it. Then, by disciplined labor (whether it is described as philological or hermeneutic, or whether it is simply the acquisition of a perfect knowledge of a text or a corpus, of texts), make yourself able to use the gift.