The Fletcher family’s American experience stretches back to the very beginning of the European presence in New England. The family descends from Robert Fletcher, who settled in Concord, Massachusetts, in 1630. Jesse Fletcher, the patriarch of our story, was among the sixth generation of Fletchers in America. That generation made its mark not as founders, but as patriots, for it was the American Revolution that shaped and gave meaning to Jesse and his family. Born to Timothy and Bridget Fletcher in 1762 in Westford, Massachusetts, a small farming and cattle-raising village about twenty miles west of Boston, Jesse was the youngest of four children. His eldest brother, Elijah, became an ordained Congregationalist minister in nearby Hopkinton, Massachusetts, in 1773. But it was his brother Josiah to whom Jesse remained most attached, especially with the outbreak of hostilities at Lexington and Concord in 1775. Josiah was among the Minutemen who answered the call at Bunker Hill. Although he was only thirteen at the time, Jesse acted as an aide to Josiah during the very battle at which blood was first spilled in the American Revolution. Josiah went on to serve as a private in the Massachusetts militia at Ticonderoga, White Plains, and Saratoga.1

After the war dozens of Revolutionary soldiers from the Boston area—many of them men who had served in the same militia company—made their way northwest into Vermont for fresh land. Some nineteen war veterans from Westford alone migrated with their families to Cavendish and Ludlow, Vermont, in the mid-1780s. They chose the rolling alluvial hills and valleys at the foot of the Green Mountains in part because the area had been well known to soldiers as far back as the end of the French and Indian War in the 1760s, when British general Lord Jeffrey Amherst carved out the Crown Point Road through the northeast corner of Ludlow. The road opened a flow of intelligence, arms, and men between Massachusetts to the east and New York to the west that helped counter French and Indian raiding parties coming out of Canada. So the northwest migration into southeast Vermont was itself an artifact of war, and Josiah and his friend Simeon Read were the very first settlers who moved into the area and began clearing virgin soil on the flats bordering the Black River, on the east side of the present-day town of Ludlow.2

With Josiah’s example before him, Jesse was a good candidate for a migrant out of Westford. Growing up in a humble family on a small farm with little access to any sort of advanced education, Jesse matured quickly, especially in wartime. He courted a local Westford girl, Lucy Keyes, and on August 8, 1782, they were married. He was nineteen; she was sixteen. The next year, now with an infant girl, Jesse and Lucy ventured up to Ludlow to visit Josiah and his family. They liked what they saw. Jesse found an especially alluring fresh spring along the banks of the Black River and, with the help of his brother—who, as town clerk, was able to cheaply snatch up various properties in Ludlow that were being auctioned off for delinquent taxes—decided to make the move to Ludlow too. In 1784 Jesse built his log cabin along the little stream that ran near the base of the Green Mountains. It was a very simple move for a young family with few skills and almost no resources. “They came in an ox cart to the place over the most rugged road,” his son Calvin recalled.3

Early settlers like the Fletchers built log houses with roofs made from tree bark, which meant felling a lot of trees to make clearings. Fellow settlers came together as neighbors for “logging bees” to do the clearing, rolling all the logs into huge piles and burning them. One old resident in the mid-nineteenth century recalled standing at his father’s house as a small boy and counting the fires of some seventy-five different chopping areas where land had been cleared.4

Like many other young men and women of the Revolutionary generation, Jesse and Lucy began their life together as migrants “quite young & inexperienced,” as one of their children later remembered. A short, stout, sandy-complexioned man, Jesse had to make the best of things as he struggled to till the unforgiving soil, rugged rocks, and unimproved forestland of his one hundred acres in Ludlow. “My father had no money,” one of Jesse’s sons recalled, and “had to rely on his own energy” rather than any skills as a trader or experienced farmer. He and Lucy labored hard and lived poor. Grass and hay were cut by hand using thick, clumsy scythes fastened to large, heavy iron bands—not a task for old men or weak boys. As parents, Jesse and Lucy had to endure their share of personal tragedies. Their eldest daughter, Charlotte, died at age twelve; their son Stephen was run over by a horse and killed when he was only six. Given their large and growing family—fifteen children over the years—Jesse built a larger frame house in 1805 to accommodate their growing household.5

Despite their relatively primitive rural setting—or perhaps because of it—both Jesse and Lucy worked hard to instill the importance of education in their children. A small, shrewd woman, Lucy reportedly had unbounded confidence in her children, provided they were willing, if need be, to leave home and go out and compete for their own independent fortune and place of honor. Family lore claims that when Lucy stamped her foot like a rabbit, all arguments ended and she got her way. It was a trait that only grew stronger with time. Many years later, in 1831, when Elijah, one of her older sons, ordered the youngest, twenty-two-year-old Stoughton, to “go cut that field of rye,” Lucy reportedly stamped her foot. “No, you will never touch that scythe again,” she told Stoughton. “You are going out into the world to make your way.” She gave the boy a horse—just a nag—and a few dollars and sent him off. What she lacked in literacy and education—she could write her name and read a bit, but could do no more—Lucy made up with faith and hard work. A Baptist her entire adult life, she held fast to the word of God and busied herself sewing clothes and laboring on the farm both for her family and for the poor. She carded, spun, and wove the woolen cloth for the winter clothes of some fifteen children. When her son Calvin became wealthy later in life, he wrote his mother asking her to make him a suit, since her cloth, he insisted, was better than any he could buy, and she was clearly the best tailor he’d ever known.6

But both Jesse and Lucy fully grasped that hard work was not nearly enough to guarantee a happy and successful future, especially for their children. Becoming educated—or at least acquiring basic schooling—was a central tenet not only in their childrearing but also in their view of what made a person truly useful in the world. So despite their meager circumstances and the pioneer world of rural Vermont into which they had moved, they were determined to find schooling for their children. And here they relied again on Jesse’s brother Josiah. Besides being a working farmer with a thriving real estate business, Josiah Fletcher also taught school, initially out of his own home. In the village, Jesse followed his brother’s lead, taking on the responsibility of arranging schooling for the settlers’ children. But progress came slowly. The settlers were thinly spread out over the township, and many of them were very poor, resulting in too few students and too little personal capital available to support a local school. As one of the town’s selectmen, Jesse urged the raising of money from individual families. On April 10, 1801—some eighteen years after initial settlement—the town voted to raise $66 from contributing families to build a modest, one-story frame schoolhouse, twenty by twenty-four feet. Each student had to furnish two feet of wood for the school. In its first year some fifty-seven students were enrolled, most likely including Jesse’s youngest children: Stephen, seven; Lucy, nine; Timothy, ten; and Elijah, twelve.7

In such a primitive setting only the basics were taught—reading, spelling, writing, and elementary math. Penmanship was difficult to teach, as it required making and mending the quill pens that the students used—steel pens didn’t come into use until the 1830s. Girls were taught the art of needlework, which, once completed, created a “sampler,” a square of canvas on which the alphabet was displayed in various colors and forms. The girls’ parents often proudly framed and hung these samplers up in the best room of the house.8

What mattered most to Jesse was that his children work hard and become “useful” adults with strong moral and religious principles. Although he never formally joined a church, Jesse attended Congregationalist services and was deeply imbued with religious feeling. According to his son Calvin, Jesse drew his whole worldview from the Bible, believing in “a direct superintending Providence, punishments & rewards.” He never went anywhere without his Bible and a newspaper and regularly read aloud from the Scriptures with his family. Despite this strong moral grounding, Jesse led a somewhat timid and fearful life—always struggling to stay out of debt and, with such a large family, often worrying that he was failing at his responsibility of taking the best possible care of them. Indeed, he suffered frequent bouts of “depression of spirits,” as one son called it, a condition that may well have prompted him to indulge in excessive drinking in his middle age. Despite these financial worries, he made himself a very “useful” figure in Ludlow politics. In addition to serving as a town selectman, Jesse was elected the first town clerk and recorder of all deeds and birth, marriage, and death records. From 1798 to 1799, he followed in the footsteps of his brother Josiah, representing Ludlow in the Vermont legislature and also serving as justice of the peace for nearly thirty years.9

Given their relatively impoverished agrarian circumstances, Jesse and Lucy understandably wanted to make sure their own children could imagine a future beyond becoming poor plowboys in rural New England. This desire underscored for Jesse the necessity of providing his children a serious education beyond the simple elementary training available after 1801 in Ludlow. In fact, according to his sons, he didn’t think much of people who had not pursued a liberal education. His brother Elijah had attended college, and Josiah had begun college, though he was unable to finish. At minimum, Jesse wanted to make sure that all of his own children had at least a rudimentary formal schooling. And, as in many farm families with limited resources, he privileged the eldest children (especially sons) with the most elaborate educational plans. “The first children received more personal attention in their education from my father than the middle & last,” one of his youngest sons, Calvin, remembered.10

So it was not surprising that when Elijah, one of Jesse’s older sons, showed promise in his studies, he became the focal point for his family’s hopes for a college education and a future that would send him away from home, a home he loved but that offered mostly poor and hopeless prospects. Clearly a young man with scholarly potential, Elijah was sent out as a boy of fifteen to live with his grandmother in Westford and attend the Westford Academy to prepare for college. The cost of going to college in the early nineteenth century—paying for tuition, room and board, and tutors, and suffering the loss of able-bodied labor back home—proved prohibitively expensive for most families. Only the truly gifted, the well-to-do, and the most determined made the choice of pursuing a college education. Elijah was one such young man. He attended college at Dartmouth and Middlebury, and then, in the spring of 1810, he transferred to the University of Vermont, where he finished his liberal arts degree.11

He was about to embark on what would become a signature theme among the Fletchers, especially its young men: leaving home at an early age to find a better future. It was a departure fueled by equal parts hope and desperation.

* * *

At eight in the morning of July 4, 1810, a slender, twenty-year-old Elijah Fletcher mounted his bay mare outside his family’s modest frame house in Ludlow, Vermont. Fresh from his college education at Middlebury and the University of Vermont, and wearing clothes spun and woven by his mother and sisters, Elijah bade farewell to his impoverished farm family. He had a teaching offer at an academy in Raleigh, North Carolina, that paid well and so was an alluring prospect. A few months before he left, Elijah admitted that “the thoughts of six hundred dollars per year has such influence upon my mind that I am employed in contriving a plan for affecting the object.”12 Teaching school in the “distant country” of the American South offered a powerful alternative to the drudgery and dead-end farmwork that lay before him if he stayed behind to help his father and brothers. In fact, life in Ludlow working Jesse’s farm conjured up thoughts of nothing but hardship and debt. “My inability and dependence made me miserable while with you,” Elijah later confessed to his father. “Such was my determination when I left home that nothing but death or a total deprivation of corporeal strength would prohibit me paying my distrusted and at best fast-bound debt of gratitude. I would rather [have] labored in the field with the negro slave and so earned a recompense for your kindness than have involved you in difficulty.” Leaving behind his often-depressed and struggling father—even with several other sons and daughters to help out on the farm—Elijah rode off that day under a cloud of presumed self-centered motives, a suspicion that continued to gnaw at him months later. Even his friends in Ludlow, he confessed, “doubted my affection for the family and said my motives were all selfish, I had a care for nothing but to aggrandize myself.”13

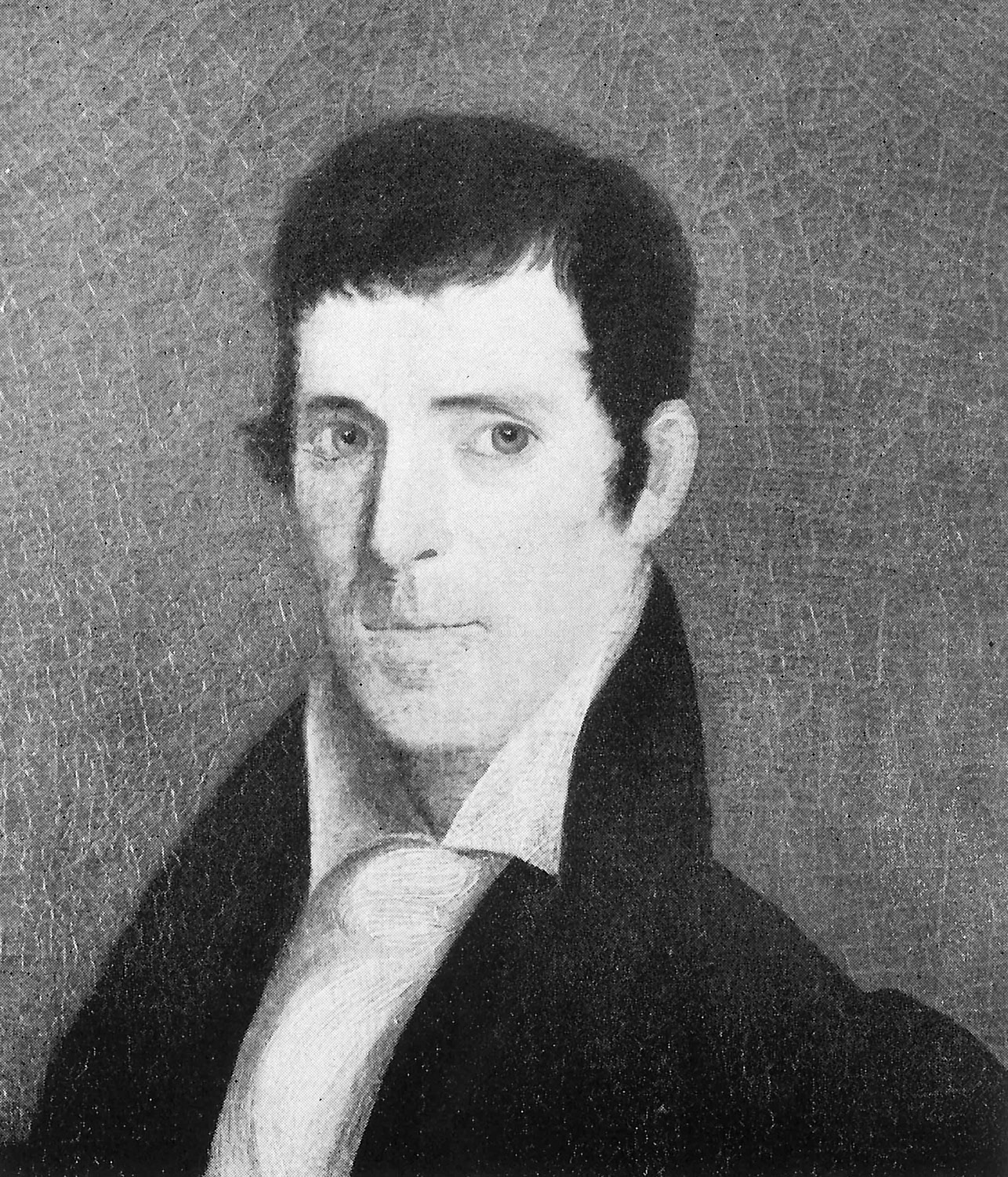

Elijah Fletcher, ca. 1815

Part of Elijah’s “selfish” agenda surfaced in his effort to coax the University of Vermont into granting him his diploma “without I tarried till Commencement.” When that was granted, all he needed was $50 to cover the diploma and a means of travel: “Trust me for a horse,” he wrote his father from college, “[and] I shall be ready for the expedition.” A final task was to secure some key letters of recommendation to take with him. The first day of his journey was a thirty-two-mile ride to Manchester, Vermont, followed by eight more miles to Arlington, where he had to wait on a letter from Governor Isaac Tichenor. He was told to go to Bennington, where the governor, out fishing, prompted “another disappointment.” Instead, two hours later, he managed to obtain a letter from Vermont U.S. senator Jonathan Robinson.14

Armed with a diploma, a letter of introduction, and a few dollars, Elijah finally grasped how daunting his “long and strange journey” would be. Calculating that he could ride forty miles per day, he figured he would arrive in Virginia in a little over two weeks. Confident that his “expedition” was necessary, Elijah nonetheless keenly felt the potential danger and uncertainty of the path before him. As he was about to head south from Albany, New York, he admitted to his older brother, twenty-three-year-old Jesse Jr., that he had fallen into a “hypochondriacal or melancholy reflection when I consider I have seven hundred miles to travel, with nineteen or twenty dollars to bear my expenses. However, I will do the best I can. I am in no fear of starving, although I must live prudently.”15

Living prudently meant finding cheap taverns for meals and lodging along the way. To conserve his meager funds, Elijah subsisted on bread and cheese and, when “the gnawings of hunger compelled me,” a cup of milk. When he stayed at a Dutch tavern in New York, he asked the female proprietor for a little milk. Her response was prophetic in terms of the cultural shift he was in for as he moved south: “The good woman wanted to know if I chose sweet milk? No, I told her, I did not want my milk sweetened. She says: you don’t understand me, do you want sweet milk or sour? I laughed at my mistake, and told her I was a Yankee; I preferred sweet milk.” During his journey he mostly tried to appear “a liberal gentleman” among strangers, when in fact he “was as poor as Job’s Cats . . . thus did pride struggle against poverty.” Sometimes, though, meeting and staying with suspicious strangers prompted fear and anxiety. At one tavern in New Jersey, Elijah noted, “I went to bed, and slept but very little, for the house was full of swearing, drinking, Irish gamblers. They tried to get me into their company before I went to bed. I told them mildly I was unacquainted with their game and thus excused myself.” The landlord worried him nearly as much as the dubious lodgers. Before going to bed, he asked the owner for his luggage, “telling him I should want to change my clothes, when in fact I was afraid to trust them with him. I spent a restless night, with many fears, and apprehensions of robbery, murder, and the like, but was so fortunate as to find myself alive the next morning.”16

Nearly every place he rode through revealed a surprising landscape. And he clearly found the differences from his ancestral home in Vermont fascinating and worthy of ethnographic reportage. Fletcher witnessed “truly excellent Land and some fine plantations” along the banks of the Hudson but thought the people looked “indigent despite being wealthy Dutchmen.” He caught sight of log homes in New Jersey, but in Pennsylvania, he reported, nearly all the buildings were stone houses and barns, mainly inhabited by Germans, “an inhospitable, ignorant, uncouth set.”17 After leaving Philadelphia, he took a back road to avoid the more heavily taxed turnpike, but in doing so, he temporarily became lost. As he headed south of Philadelphia, Elijah reported his first signs of slavery: “I saw herds of negroes in fields—men, women and children, some dressed in rags, and others without any clothes.” Traveling the final leg (forty-six miles by his calculation) from Baltimore to “Washington City,” he found “scarcely an inhabitant” along the way. There were very few taverns, he lamented—mostly just poor people scattered far from the main road. After nearly drowning while trying to ford a creek in Maryland and soaking his clothes, Fletcher looked in vain for a place to dry out. Finally he saw a “little hut” with a little girl standing by the door. She told him the humble little structure was an “ordinary for such they call taverns.” Elijah got off his horse and went inside. “I thought it was an ordinary indeed,” he recounted. “No body at home, but the girl and another little bare-assed child. I told her my misfortune and desired her to make a fire that I might dry my clothes. I felt hungry, anxious and much provoked to think I must stay two or three hours to dry my clothes, but I had endeavored to make the best of all misfortune, and not despond at trifles.” He asked the girl for some milk and bread. She gave him “a dirty pint tin cup full” of milk and baked “a jonny cake” in the fireplace. “I ate a little of it,” Elijah wrote, “dryed myself and travelled on my way, rejoicing that I had escaped being drowned.”18 Elijah clearly could be judgmental, yet, given his youth and the strain he was under, he also possessed a powerful streak of optimism and resolve.

Soon after his arrival in Alexandria, Virginia, Elijah made the fateful decision not to push on to Raleigh for the teaching appointment he had originally agreed to take. His long and laborious journey from Ludlow had left him with an ailing horse (“very poor, sorebacked and shabbed”), and, once in Alexandria, he made the acquaintance of another young teacher in the area who happened to have friends in Raleigh and “solicited an exchange of situation.” Elijah eagerly agreed to the switch: his friend would take the Raleigh job, and Elijah would take the other’s position teaching at the Alexandria academy. Although he had never been to Raleigh, Elijah felt immediately confident about his change of plans: “I think I have made a good exchange. I know it is equally profitable and I doubt not it will be equally pleasant.”19

Alexandria, “one of the largest, handsomest, and most commercial cities in Virginia,” struck Elijah as a very pleasant place with a brisk trading business along the Potomac River. His academy was situated away from the center of the city. There he taught some fifteen “scholars” ranging in age from thirteen to twenty, instructing them in math and English grammar, and boarded with a “nice genteel family” of the well-to-do planter General Thomas Mason, “a man of note and respectability” who was son of the prominent Virginia Founding Father George Mason. As Elijah soon realized, he was now ensconced in a place where great wealth and slavery were on full display, a point he was unafraid to convey to his antislavery “Yankee” father back home. “Our living is rich,” he wrote his father, “and what in Vermont would be called extravagant. . . . I also feel independent, have two negroes at my service and live considerably at my ease.” He was practically giddy over how clever and comfortable he felt living in the “distant country” of Virginia. “I am so satisfied with my employment, so pleased with the people, and so agreeably situated every other way that I would not exchange my situation for any I ever held in Vermont,” he wrote.20

As if he could sense his father shaking his head in doubt, Elijah was at pains to acknowledge the quite visible social and cultural differences he saw all around him. “To be sure,” he wrote, “I find the manners and customs of the Virginians different from the people in the North, but the difference I think habit will soon make a pleasing one.” First, there was the Virginians’ well-known fondness for sports and socializing, especially “Barbecues and private parties,” which Elijah claimed to find “novel and amusing.” But he was clearly also taken by his new planter friends’ “open-hearted liberal sentiments, a certain noble spirit and social feeling, which distinguish them from the Yankee or selfish, narrow, earthborn-souled Vermonter.”21

To his older brother Jesse Jr., charged with helping run the family farm back home in Ludlow, young Elijah offered a more critical perspective on his new southern surroundings. While he remained serenely confident about his academy—“I have found no difficulty as yet in governing my scholars. They appear to be very studious and tractable . . . much better than I expected”—he was clearly shocked by the master–slave interactions he observed every day on Mason’s plantation. “The planters and their sons,” he told Jesse Jr., “appear and dress with rich and neat apparel. They live in idleness and some in dissipation.” The rich planters owned from fifty to one hundred slaves, he noted, and “they buy, and sell them, as we do our cattle. . . . Some men make it their principal business to buy droves of them, and drive off, as our drivers do cattle.” Most slaves were dressed in rags, except the children, “who [go most]ly naked.” Overall, “they have but very little to eat and are under the constant eye of an overseer, who makes them work from sunrise, till sunset.”22

But what really troubled Elijah was the harsh and often-inhumane treatment he witnessed masters inflicting on their slaves. “They whip them for every little offence most cruelly,” he observed shortly after arriving in Alexandria. He told his father the story of General Mason who, upon discovering that one of his slaves had borrowed Elijah’s horse for a brief joyride, “tied up the boy and whipt him about a quarter of an hour, and he was begging and praying, yelling to a terrible rate. They then took the man, and I will assure you, they show him no mercy. The more he cried and begged pardon, the more they whipt and in fact I thought they would have killed the poor creature.” When Elijah explained to Mason that he didn’t really mind the slave borrowing his mare, he was quickly rebuked: “They said it would not do to indulge them. They must whip them till they were humble and obedient.”23

Elijah’s depiction of slavery veered between sympathy for the ill-treated slaves and disdain for how “the negroes” lived. While he noted that slaves looked down on their white overseers (“the negroes think as meanly of the poor white people, as the rich white people do themselves”), he was contemptuous of the primitive and promiscuous existence he perceived them as living. Slave marriages, he pointed out to his brother Jesse, amounted to little more than casual, informal agreements. “They have but little more ceremony about such things than the cattle do,” he wrote. “They lay all together on the floor like hogs, have no beds. The negro women have a great many children,” which they began to conceive in their early teens. “There is such promiscuous intercourse between the sexes,” Elijah concluded, and, with “no regard to decency or chastity, they will have as many children as a bitch will puppies.”24 Left out of this harsh commentary was not only any sense of moral judgment about the institution of slavery itself, but also any recognition that slave marriages were not legally recognized in the South.

Such a scathing assessment of slave morality prompted concern from Elijah’s father. An antislavery man with Puritan roots, Jesse Fletcher Sr. not only took a dim view of white masters in the South but strenuously pressed his son to do his part to right the many wrongs of chattel slavery. Caught between respecting the New England antislavery precepts his father had taught him and needing to justify the dramatically different necessities of his new plantation surroundings, Elijah did his best to explain himself to his concerned father. “You wish to have me relieve and assist the slave in distress,” Elijah wrote. “I assure you it is a task I would do with pleasure, if I could with profit.” What he meant by “profit” was his rising place in the Virginia ruling class, something he was becoming reluctant to endanger. Thus he believed that honoring his father’s request that he assist the poor slaves would only harm his own status: “To vindicate the rights of that degraded class of human creatures here would render me quite unpopular. There are none the Virginians despise so much as Quakers and those who disapprove of slavery.” Still, Elijah insisted, he cautioned slaves to behave with “obedience and resignation,” and he treated his house servants “kindly,” even attempting “once in a while to save their black backs from the lash.” Unlike General Mason, Elijah protested, he didn’t engage in scoldings, threats, or “cruel whipping”; instead, he tried to encourage them as best he could. In the end, though, there was little hope for the slaves. Because they were illiterate, possessed no political rights, and had no ambition and “no chance to rise and become eminent,” black slaves existed at a level far below that of even the poorest whites Elijah had seen all around him in Vermont. “Happy, thrice happy are the poor people of New England when compared to that class here,” he told his father.25

Given such a dark picture of southern culture, it was scarcely surprising that many young men from the North who moved south in the early nineteenth century to take advantage of teaching positions simply couldn’t adapt to a world of harsh slavery and white dissipation and extravagance. Yale graduate–turned–plantation tutor Henry Barnard regarded the residents of Chapel Hill, North Carolina, as “indolent” people who, “like most southerners[,] . . . like very much to lounge about and let the slaves do the work.” Repelled by the alien and often-distasteful customs of the southern ruling class, many of these young “Yankee” instructors fled back to the more familiar world of the North.26

But Elijah stayed, in large part because he saw real opportunity—both financial and personal—in the “respectable” plantation world into which he quickly ingratiated himself. In fact, less than a year after arriving in Alexandria, Elijah chose to deepen his commitment to becoming a southern man. In March 1811, he responded to an invitation from a prominent lawyer and large planter, David Garland, to take over an academy in New Glasgow (now Clifford), Virginia, over 200 miles to the south. In explaining to his father why he was moving, especially since his position with General Mason was “agreeable,” his “salary decent,” and the general wanted him to stay, Elijah made it clear that it was his “ambition” for profit that propelled him. “I should have a larger salary (which is my first object),” he observed.27 Moving himself away from debt and closer to the world of genteel planters formed the core of Fletcher’s game plan as he began his new adventure in Virginia.

He traveled first to Charlottesville, where Garland provided him with a horse and servant to take him the remaining forty miles. During his stay in Charlottesville, Garland also arranged for Elijah to get “an interview with the Philosopher of Monticello.” When the young man arrived at the top of the mountain, “Mr. Jefferson appeared at the door.” They repaired to the drawing room, where “wines and liquors were soon handed us by the servant.” Elijah’s recounting of his visit with Thomas Jefferson revealed his largely disrespectful, disapproving impression of the former president. Retired from the presidency, Jefferson had been the subject of nine years of scandalous gossip over his rumored relationship with his slave Sally Hemings. “I confess I never had a very exalted opinion of his moral conduct,” Elijah told his father, “but from the information I gained of his neighbors who must best know him, I have a much poorer one. The story of black Sal[ly Hemings] is no farce. That he cohabits with her and has a number of children by her is a sacred truth, and the worst of it is, he keeps the same children slaves, an unnatural crime” that to Elijah was “so common that they cease here to be disgraceful.”28

If his journey to Monticello suggested that Elijah hadn’t yet made complete peace with Virginia’s slave culture, his relocation to the hills of New Glasgow soon brought him much closer to a position of acceptance. A small village of about 200 people, located twenty miles northeast of Lynchburg, Elijah’s new home at the New Glasgow Academy gave him a “handsome dwelling house for myself,” complete with a classical library and surrounded by a few acres of land.29 Even more appealing was the opportunity to meet eligible, well-to-do young women. “I am quite the favorite of the ladies about here,” Elijah boasted to his sister Laura. The teenage “ladies” he instructed in French out of his home sent him gifts (four pounds of cheese, a prayer book, and cotton stockings from one girl “which she had knit with her own hands”) and, when they came to recite their French lessons, would sometimes bring him fruit “with the first letters of their names marked upon them.”30 Elijah could well have used the gifts of food: he reported that he weighed only 129 pounds at the time.

Most significantly, teaching at the academy offered Elijah the chance to meet nineteen-year-old Maria Antoinette Crawford, one of his students and, just as important, the daughter of William Crawford, a distinguished lawyer and wealthy plantation owner in New Glasgow. At Christmas of 1811, he confessed to being swept away by Maria’s charms. He had “become acquainted,” he told his father, “with a young Lady . . . of amiable manners and disposition for whom I have more than common [regard] & with whom I am on terms of intimacy.” At first, he was determined not to let the allure of romance impede his economic success. “Giving away to the softer passions & feelings in too great a degree is detrimental to my worldly interest,” he wrote. But nearly a year later, his courtship had grown into “a subject of serious thought,” and it was time to make a full case to his father regarding Maria’s—and her family’s—reputation and importance. Referring to Maria as “a most amiable, accomplished, sensible Lady,” the daughter of “one [of] the most rich, extensive, respectable families in the State,” Elijah wanted his parents to know that in Maria “I have a bosom friend and connections about who will feel an interest in my fate.” Deflecting the appearance that economic security rather than genuine affection was fueling the match, Elijah told his sister Lucy (who was herself contemplating marriage), “Property is desirable. It adds to the comforts and conveniences of life. But property alone cannot make us happy.”31 But he was just as concerned to reassure Jesse Sr. and “Ma’am” (as Elijah referred to his mother Lucy) that they would remain “my first best human friends.” “If I have chosen a companion recently,” he carefully pointed out, “my highest esteem, dear to me as life itself, my filial regard for you is unaltered.”32

One can scarcely imagine the worry and concern that must have seized the Crawfords as they watched this courtship unfold. On the positive side, Maria must have been truly drawn to Elijah by romantic love, since he brought almost nothing by way of property or status to the relationship—a problem that doubtless the genteel Crawfords fully grasped. Wealthy planters like the Crawfords routinely guarded their families from intrusions, especially those involving “Yankee” outsiders like this Vermont tutor. But they may also have sensed that Elijah Fletcher, unlike most visiting teachers from the North, was fast becoming something of a convert to the southern way of life. For his part, Elijah happily reported that the Crawfords lived “in the genteelest style” in a carpeted, two-story home called Tusculum. “Mr. C” was a man in his fifties, “quite grey headed, educated at Princeton, formerly a distinguished lawyer.” Maria’s mother, Elijah noted, “is a most amiable woman.”33

On April 15, 1813, Elijah and Maria were married and soon began to live “in the Virginia style,” with a comfortable home, plenty of whisky or wine for visitors to drink, and “black servants enough.” “Tell Ma’am,” he wrote his father, “we have good Imperial tea and coffee.” Married life clearly agreed with Elijah, and he marveled at how his life had changed in so many unexpected, if welcome, ways. “Little did I expect three years ago to be in such a situation as I am,” he told his father two months after his wedding. “How little do we know what a day will bring forth.”34

One thing he felt certain the day would not “bring forth” was children. “We have no children,” he told his father, “and hope and pray we never shall have any.” While Elijah understood that children often proved a source of comfort and consolation to parents, he felt that offspring “more frequently prove a vexation. Hardly any family where they all do well.” In what was no doubt a commentary on the inconsistent, uncertain outcomes he had witnessed in his own family, Elijah adopted the cynical position that whatever parents’ most fervent hopes for their children might be, “they are too frequently blasted.”35

If the newly wed Elijah was renouncing parenthood, he was most certainly not condemning his newfound wealth, not to mention his much more public embrace of southern slaveholding culture. Linked by marriage to one of the leading planters in Amherst County, Elijah now possessed a kind of financial security never experienced by anyone thus far in the Fletcher family. He even suggested that his father brag about his financial success in Virginia to his friends back in Vermont: “You may tell our good friends in Ludlow that I have become President of an Academy here with a salary of a thousand dollars per year which will do for their envious spirits to gnaw upon.”36 But Elijah was also a man of generosity: he quickly and effectively assumed the mantle of moneylender and family advisor to all his kin, especially his impoverished and unhappy father.

Jesse Sr. was now over fifty, in poor health, and unable to scratch out much of a living from his small farm in Ludlow—even with several sons and daughters around to help out—and Elijah fully grasped his father’s precarious plight. Before he married Maria and securely settled into his position in New Glasgow, Elijah tried to sympathize with his father, claiming that early on he also felt “poor and dependent,” but, as he told his father, “I know your wants are so urgent . . . I frequently ask myself when I shall be independent and not dogged about and troubled for want of money.”37 And so, from the beginning of his time in Virginia, Elijah began sending his father and siblings money, almost every month—usually $50 to $100 in hopes the money would lessen “your fears & ease you a little from your embarrassments.”38 Nearly every letter Elijah received from his father contained not only another request for money but a melancholy lament about his poverty. “I am sorry, daddy,” Elijah wrote in 1813, “you are so poor in spirit.” When Elijah directed him on how exactly he should distribute one particular batch of money he had sent them, Jesse complained about his over-controlling son. “You say the rich cannot sympathize with the poor and intimate as tho I wanted feeling,” Elijah shot back. “After reading the first page of your letter I stopped, I laid down the letter and cried. It made me so melancholy to think my good Father was not happier. Oh, thought I, were the mines of Mexico mine, how gladly would I share them with you.”39

As much as he loved his father and seemed almost desperate to be thought of as a respectful and dutiful son, Elijah also wondered why a man who had worked so hard and was surrounded by such a loving family could become so dispirited. After getting yet another letter that “breathes the accustomed melancholy, doubt, and difficulty,” Elijah confronted Jesse Sr. about the meaning of his life, past, present, and future:

I presume you think your lot is a hard one. I am sensible from your first setting out in life you have encountered many a hardship, trial and trouble. You first penetrated into a wilderness country, had few neighbors but the wild beast of the forest and encountered all the inconveniences necessarily attending such a situation. You have supported a very numerous and expensive family by the mere earnings of honest industry, always too noble-hearted, upright, and honorable to descend to the arts of cunning speculation to take advantage of the weakness and necessities of your fellow creatures. It melts my heart quicker than anything else to think, after so many troubles, you cannot enjoy a happy old age, and go down to the tomb in peace, plenty and quietness. I hope this will be the case. I hope a brighter sun will shine upon your prospects.40

Nothing brightened one’s prospects, according to Elijah, like a good education. If only Jesse Sr. in his youth had had the opportunities for learning that were made possible for Elijah and several of his brothers and sisters, things would have been different. “Omit no opportunity in learning,” Elijah reminded his seventeen-year-old brother Stephen as the younger Fletcher prepared to go off to college. Strategizing with his father about whether to give young Stephen property or an education, Elijah contended that “a little advantage for an education is the best portion you can give him.” He went on to advise that “if you can keep him at school two years and he makes good advancement in study, I can get him into business here,” in Virginia, where Elijah predicted his brother could earn $300 to $400 a year. Jesse eventually agreed, and when Stephen went off to Middlebury College, Elijah rejoiced, hoping that such a commitment to his brother’s education could be made without selling the family farm, as so many gossiping neighbors in Ludlow had predicted would happen ever since Elijah had gone off to college. “Let the envious grind and gnash their teeth as much as they please,” Elijah advised his impoverished father. “The only way of revenging ourselves upon them is by doing well.”41

And education, Elijah insisted, was just as important for women. As his younger sister Lucy reached eighteen years of age, Elijah emphasized how critical it was for her to follow the educational path that had led to his own success. “A girl will be more respected with an education than with wealth,” Elijah wrote after sending Lucy $100 to help defray the cost of her schooling. “I think female education is too much neglected. They are the ones who have the first education of children and ought to be qualified to instruct them correctly.”42 While it was increasingly common in the early Republic for ambitious young men to focus on the necessity of an education, Elijah’s conviction about the equal value to be placed on schooling young women represented a uniquely progressive position in his day, one that would lead to an unexpected but revealing personal legacy.43

* * *

Still in his early twenties, Elijah Fletcher was fast developing a durable—and, for him, successful—personal credo. Personal ambition rather than faith or entitlement fueled the young Fletcher’s life. “I am one of those ‘wicked ones,’” he told his father early in his Virginia adventure, “who put great dependence upon works; and verily believe my future success will depend rather upon my own exertion, perseverance, prudence, and economy than on the Fates, Fortunes, Destinies, that can be mentioned.” And, unlike today, there was no help, no cushion, and no safety net from society for those whose efforts came up short or ended in failure. The fate of a young man like Elijah truly rested on his skills, determination, and luck—and little else. Understandably, then, the culture placed a huge premium on hard work and self-sufficiency. Like increasing numbers of young men in the early Republic, especially those who had uprooted themselves from their ancestral homes in the East for new prospects in the South and West, Elijah fully embraced the ethos of self-reliance and self-advancement. “I have an ambition to make myself respectable,” he wrote. “I am sensible I possess no extraordinary gift or talent, and to gratify my ambition nothing will do but industry, labor and the practice of virtue.”44

But it was the “practice of virtue” that was the rub for young men like Elijah Fletcher. Receiving an education, moving away from family and friends, and making a new life in a very different, even alien, place like the slave South—all of this self-improvement, risk taking, and adventuring in “a distant country” sometimes caused some very difficult moments with family back home.

Nowhere was Fletcher’s “virtue” more contested than in his growing embrace of Virginia slave culture. From the beginning, Elijah’s father had pressed him about the unfamiliar world of these wealthy southern planters and the chattel slaves they controlled. Finally, three years into his time in Virginia, Elijah reached the breaking point. In response to more of his father’s “questions about our people here,” Elijah wrote, “I rather think you have too bad an idea of them. There are a great many good men here as well as many bad.” Furthermore, he argued, his father’s idea of emancipating the slaves “would be the height of folly and danger.” Now married into plantation society, Elijah had become a partial defender of slavery, seeing it as “rather a misfortune than a crime.” The present generation of slaveholders, he argued, could not be condemned for something their fathers had done, namely, introducing slavery in the first place: “They are only censurable for not treating those they possess well.” To Elijah, those slaves with enlightened, humane masters “are in a better situation” than they would be otherwise, a common rationalization among southern slaveholders. Elijah tried to pass off his conveniently changing perspective on slavery as simply what happens when ideology—such as his father’s antislavery notions—confronts daily reality: “I know what horrid ideas I formerly had of slavery,” he wrote, “and how I despised the man who would traffic in human flesh. My feelings may be a little softened by living in a country where such things are common, but they never will be perfectly reconciled to them.” But then came the real blow: “You must not think too badly of slave holders,” he cautioned his father, “for your son is one.”45

Although he struggled with his father over slavery and Jesse Sr.’s chronic financial needs and “melancholy spirit,” Elijah loved him deeply, sometimes even desperately. The physical distance between them only heightened his yearning for his father and the family he had left behind. One summer Sunday morning, Elijah decided to reveal his feelings. “My thoughts are with you,” he wrote Jesse Sr. “I have sat me down before meeting-time to communicate a few of them.” Elijah had been thinking of home and his “dear father and mother, brothers and sisters” and was looking for “some way to speak and converse with you.” He hoped Jesse Sr. would not find it “burthensome” to pay the twenty-five cents—in that era the recipients paid the postage—“for a good long letter from me for I know you are my father, and that your children are more precious to you than money.”46

Much had changed for Elijah Fletcher since riding off from home—some of it surprising, the unexpected effects of living in a plantation setting. But much of that change grew out of the fading memories that came with such distance and time apart. He held firmly and fondly to the memory of his leave taking: “I mounted that little bay mare and left the house of my Father. I cannot reflect on that time but with mingled emotions.”47 And those reflections left him at least occasionally homesick. “I long to behold the sacred spot of my nativity and its inhabitants,” he wrote. “I frequently think of the changes that has probably taken place since I left you.”48 But without portraits or photos, and with no visits home yet, Elijah could cling only to his quickly diminishing memories as a way of visualizing his family. He told his sister Laura that “I can’t think of you as you are, but think of you as you were when I left you. I suppose you look quite different from what you did then, and that all other things are much changed.”49 Upon reading in one of the Vermont newspapers that his father was now fifty, Elijah immediately requested information on every family member’s age. “I set down your age and ma’am’s in my pocket book before I left home,” he told Jesse Sr. “I wish I had the age of all my brothers & sisters. If it be not too much trouble, I wish you would send them to me.”50

The easy solution to these frayed memories and yearnings for family would have been a trip back to Ludlow. The day he left Vermont, Elijah had promised his mother that he would be back to visit within two years. It was a promise he did not keep, and soon after arriving in Virginia he seemed aware that his departure might be permanent. After being gone only a year, Elijah advised his father to prepare “Ma’am” to accept that she might never see her son again. “I earnestly hope I shall return home and see you all again in life, health and prosperity,” he said, “but my return is enveloped in the darkness of futurity. It does no good to trouble ourselves about it. All we can do is to wish and pray for the best and leave the residue with God.”51

But in time Elijah began to feel the pain of separation from his family, living so far away. Once that pain was produced by a vivid homecoming vision: “I dreamt last night that I was at home, that I saw you all, that you were much altered. Even the vision was exquisitely pleasing—how much more will be the reality!”52 But that reality did not happen anytime soon. On July 2, 1814, Elijah Fletcher stopped to contemplate his fourth anniversary of leaving Vermont for Virginia. “Little did I imagine then that four years would revolve ere I had the pleasure of seeing you all again,” he conceded to his father. “Tho’ I live in hopes that two years more will not pass away before I revisit the Green Hills of the North.”53

* * *

Elijah did not return home just yet, but he did get an inspiring and unexpected glimpse of it: his cousin John Patten arrived in late June 1815 from Boston. An aspiring businessman looking to make his way in the mercantile world of New Glasgow, Patten hoped to settle “somewhere in this southern world” and, as Elijah noted, “is the first relation I have seen since leaving New England.”54 The visit with Cousin Patten no doubt set Elijah to thinking even more about his ancestral home: “My thoughts have been more particularly roving to the north for a few days past,” he wrote, and he once again announced that, barring any “unforeseen accident,” he would visit his parents “sometime next season.” Elijah’s focus on Vermont fell just as keenly on his siblings and the uncertain future that awaited them. Seeing Patten in Virginia only deepened those concerns. “What is Calvin doing in Windsor? And where does Jesse live?” Elijah asked his father. He was especially concerned that his older sister, now twenty-nine years old, should resist the impulse to supplement their father’s meager farm income. “Tell Fanny she must not go from home to live. She must stay at home and assist Ma’am and work for herself,” Elijah insisted. “I will give her more money than she can make by going out.”55

Making money may not have seemed an appropriate goal for a young woman in the Fletcher family, but, as it turned out, it had become the guiding force in Elijah’s life, largely as a result of his marriage. When his father-in-law, William Sidney Crawford, was struck by a severe illness in the spring of 1815, Elijah watched with concern mingled with admiration: “He was sick seven weeks,” Elijah wrote, “bore his illness with the fortitude of a Philosopher and died with the composure and resignation of a Christian.” Upon Crawford’s death, Elijah was named executor of the sprawling Crawford estate. That responsibility not only consumed his time, but prompted a major change in his lifestyle: “The management of all Mr. Crawford’s affairs devolving upon me makes my task arduous. He was a man of extensive concerns and great estate. He left his affairs much deranged and unsettled, which renders the settlement of his concerns doubly troublesome.” Elijah first had to sell off the crops, especially the tobacco and wheat, which alone were worth $5,000. Then, he had “to manage all the Plantations, or at least visit them now and then to see if the overseers are going well.” One of the plantations was fifteen miles away; another, nine miles. From his perch closing up all of Crawford’s business, Elijah witnessed the human tendency toward grasping exploitation; there were so many people trying “to take all possible advantage. I have a very good opportunity to discover the rascality of my Fellow Creatures. My little experience would present a gloomy picture of human depravity.”56

Amid the “rascality” and “depravity,” though, lay a good opportunity to keep his own affairs “straight and correct,” and a profitable life as a plantation manager. Watching his father-in-law die and knowing he would be asked to supervise the far-flung plantations, Elijah made a big decision: he permanently set aside his entire reason for journeying to Virginia: the aim of working as a schoolteacher. Having already married into the slaveholding class, he would now become a gentleman farmer himself, complete with slaves and plantations of his own.

It was a transition that few, if any, of his Vermont kinsmen could have imagined, let alone applauded. But as Elijah’s younger teenage brother Calvin would also discover, leaving home was but the first of many surprises for young men on the make in the early Republic.