As Elijah pridefully observed the private world he had so carefully cultivated—his pastoral plantation life and the “enlightening” experience three of his children were enjoying while traveling in Europe—his brother Calvin, still agonizing over the fate of his own children, increasingly focused his attention on the public arena, a disturbing world of slavery, intemperance, and illiteracy. The brothers’ families thus gave expression to two equally compelling sides of the Fletchers’ American journey: an intense desire to nurture successful children for self-advancement and the felt need to remake the world in their own eyes.

For Elijah, raising children to become successful and valued citizens required both education and refinement. Like most southern planters, he associated success with a cultivated gentility reserved mostly for the elite. So he felt confident that sending three of his four children (Lucian, alas, could not be so trusted) abroad for an extravagant two-year grand tour of Europe and the Near East in 1844 would only enhance their stature as they made their way in the world. Armed with influential letters to the U.S. consulate in France from U.S. Secretary of State John C. Calhoun, Ambassador to France Rufus King, and Virginia senator William Cabell Rives, along with letters to leading French physicians, Indiana, sixteen, Betty, thirteen, and Sidney, twenty-three, took a steamship to Havre in late October and then traveled 160 miles by land to Paris. “I part with the children cheerfully (a melancholy cheerfulness),” Elijah noted, “hoping it will be for their good.” Indiana, he noted, could already speak French fluently, as well as Italian, and would serve as the interpreter for Sid and Betty. Betty delighted in “describing Scenery and passing events.” Like her older sister, she was focused on “improvement and little occupied by the light Frippery and Foolish fashions of the day.” Thanks to their well-placed contacts in France, the girls connected with royalty; they were presented to the queen and attended a royal ball. “Bettie,” Elijah wrote, “is so delighted with Paris, she wants to stay there six years. If they have health, they will have an interesting time and I hope profit by their opportunities.”1

What he hoped would result from their two years of travel abroad was a well-rounded, cultured perspective on the world rather than any sort of professional or career outcome. Elijah was in the business of polishing, not training, his daughters. And although their older brother Sidney acted often as their chaperone, he was notably engaged in furthering his own medical training in Europe. While traveling around Europe and the Near East, Sidney and Indiana wrote dozens of letters that were featured on the front page of the Virginian between January 1845 and August 1846, offering personal commentaries on the art, architecture, and lifestyles of the many countries they visited. When Indiana and Betty weren’t engaged in daily music practice and sketching, they attended plays and concerts and toured cities and the countryside in France, Germany, Spain, Italy, Egypt, and the Holy Land. Indiana’s commentary about the exotic look of Alexandria, Egypt, on October 19, 1845, in particular reveals thoughtful powers of description, especially for a sixteen-year-old, on matters of race and gender:

The novel and singular appearance of everything in the streets as we passed along awakened sensations which I shall never forget. The countenance, costume and look of the natives first attracted my attention—not a white face was seen before me—all either negroes, the dark mulatto, colored Egyptians; savage looking Turks or Arabs, almost naked, with a few clothed in costumes of the gayest colors. The women were closely veiled, wearing jewels on their ankles as well as on their toes, which are exposed to view by the peculiar fashion of their sandal . . . then the bazaars, the narrow streets crowded with camels, dromedaries, and donkeys, made me feel as if I was a stranger in a strange land.2

Elijah gave his children enormous latitude to indulge their appetites abroad, believing that his generosity was well justified by their trustworthy behavior. He told them that if they saw “anything they wish to purchase and can make the monied arrangement,” they ought “to do it.”3

Still, Elijah worried that the cosmopolitan experiences and perspectives his children developed abroad would upon their return make the simple rural world of their Virginia home feel like a backwater wasteland in comparison. Before they made their way home, Elijah betrayed this sense of cultural embarrassment: “All I want of you is when you get home to be satisfied with home as you find it,” he wrote them. “You know I am willing to improve and not niggardly in spending money for that purpose, but you know I have not had much time, if I had taste, since you have been gone, to devote to that purpose.” Promising that their mother, Maria, would help them find more fashionable furniture in New York and elsewhere, Elijah was clearly nervous that the girls would return home depressed at their simple surroundings: “I hope, I say, you will be contented with home.” He solicited the girls’ opinion regarding taste and improvements, promising that he would “only put in a word of humble old fashioned advise now and then.” His goal was to make “a genteel home in Lynchburg for a centre and then our rural establishment we will make and adorn as becomes simple rural establishments.”4

While he was willing to cater to their need for taste and refinement, Elijah went to great lengths to warn the girls against letting their recently acquired world travels go to their heads, in part because the people back home would see through any pretensions. “When you come home,” Elijah told them a month before their return to Virginia, “the people will not estimate you by your finery. They will expect from you intelligence and mental adornment and not external show. They have all read that you rode on Mules and Donkeys and horses in your travels and will think you can do the same here. The whole country will think it an honor to associate and converse with you, but will not think a whit the better of you for geegaws and finery.” His pride, though, could get in the way of his fear of pretensions: “Still,” he told them, “I wish you to appear in neat and rich and genteel apparel.”5

Sidney’s return from his European travels led him to refocus on becoming an even more successful and profitable plantation manager. A few months after coming home, he took a trip south, looking for a sugar plantation to buy. Thinking that there were greater profits in sugar than in Virginia tobacco or wheat, and hoping “to colonize a portion of our slaves in that region, being rather over stocked with them here,” Sidney looked to Florida. But he found it a “rude country,” much of it “laid waste” by the Seminole Indians. He did identify a spot on the Atlantic coast called Smyrna, sixty miles south of St. Augustine, but found the land too expensive.6

Meanwhile, the girls, much to Elijah’s surprise and delight, were “content with the monotonous retirement of this country,” spending their time reading, writing, sewing, and playing music on the piano and harp they had purchased in London. “They are likewise fond of rambling about,” Elijah observed, “and riding with me among the mountains.” His daughters were clearly his main companions, since he and Maria appear to have crafted distant, separate lifestyles in their rather unusual, detached marriage. Maria, “not liking much the country,” stayed mostly in Lynchburg, leaving her husband Elijah to supervise the country estate, Sweet Briar.7

Already a budding connoisseur, Indiana returned from the European trip with an increasingly nuanced aesthetic grasp of the many treasures her travels had revealed, from gilded harps and Italian architecture to Rococo Revival game tables and romantic landscapes. She especially had loved the time they had spent around Florence during the winter of 1845–1846 and became particularly attracted to Palladian architecture, the principles of which she would apply just a few years later in helping her father refurbish Sweet Briar. Beginning in 1851, that house took on the flavor of Indiana’s evolving tastes. Upon her advice, Elijah refashioned the place from a simple Federal-style brick Virginia farmhouse with a shake shingle roof into an elegant Tuscan villa. Drawing on her contact with Bishop Doane, whose Italian villa near Burlington, New Jersey (where Indiana had studied at the bishop’s female academy), was built in the 1830s, and her many months spent in Italy in the 1840s, Indiana confirmed her taste for the Roman style, with its arched windows and formal gardens arranged in eighteenth-century manner with marble statuary, exotic trees, and unique box hedges. At Indiana’s direction, and with some help from Betty, Elijah supervised “several white mechanics” in the summer of 1851 as they erected two three-story towers, one at each end of the house. “This is a project of my Daughters,” Elijah noted, “and as I rarely deny to gratify any of their desires, have consented to this.” A year later, square tower wings and an arched portico were added to the façade of the old farmhouse, completely altering its appearance. “I tell Inda and Bettie they will become lonesome when all is finished and they have no more to keep up the excitement,” Elijah wrote Calvin. But the girls insisted that they would be able to “amuse themselves” by taking special care of all the elaborate furnishings and decorations they had chosen themselves, mostly on trips to New York and Philadelphia.8

* * *

If Elijah Fletcher found contentment cultivating his relatively private southern plantation world in the pleasing company of his beloved Indiana and Betty, Calvin’s Indianapolis-based family was busier and more complicated than ever, and Calvin found himself increasingly immersed in a precarious, conflicted public world. When he assessed his life on his birthday, February 4, 1844, as he routinely did every year, he stressed that he owed a regular accounting to God as well as to himself—“We should often retrospect our lives,” he insisted, being mindful of “the various periods of the journey before us.” In viewing his “journey,” the forty-six-year-old observed with “gratitude” that his two oldest children, Cooley and Elijah, were progressing in school, and that among his older children, Calvin and Stoughton, had, like Cooley, joined a church—Calvin and Cooley were Presbyterians, Stoughton a Methodist. As always, Calvin looked upon all this with a bittersweet feeling: “This affords me new hopes & fears,” he wrote, concluding that his children, if “blessed with firmness & grace[,] will be well.” If they failed in their sense of purpose and gave in to wicked impulses, “they will be a reproach to their parents & ruin themselves.”9

But Calvin could become just as engrossed in worrying about what he viewed as the wicked and ruinous developments of the larger world. Raised in an antislavery family in Vermont, Calvin by the 1840s had grown into a much more vocal opponent of slavery, especially as it evolved into an increasingly visible and divisive issue in America. It was, of course, rare to witness the ravages of slavery in a northern city like Indianapolis, so when he encountered it personally while traveling, it made a deep impression. While leaving Cincinnati on a steamboat after a business trip in February 1844, he witnessed the ugly business of the slave trade: “Soon after the boat left the wharf at Cincinnati,” he recalled, “it proceeded towards the Ky. Shore & took in 4 light mulatto men & 4 women slaves—The men chained 2 & 2—all young with their ruffian driver or owner who had bot them at Baltimore & was on his way to N. Orleans with them to sell.” The slave trader, he noted, had landed them the night before in Kentucky but was clearly fearful about keeping them in Ohio overnight because of the antislavery sentiment of that northern state. The slave trader’s reluctance was the only positive takeaway for Calvin in what he saw, but he relished it: “I rejoice the boundaries are so well defined that public opinion is so determined against slavery as it can only exist by the rigid compacts of our land & where ever slavery is not justified that public opinion will not suffer it to exist.”10

The problem for Calvin and other antislavery activists was that public opinion, especially in the expanding slaveholding South, did not agree with them. And in 1844, as Texas loomed large in the nation’s discourse over slavery’s likely extension into the territories—“the great exciting question” of the day, Calvin called it—he was left to watch with horror as “demagogues” among the proslavery states manipulated “the ignorant” into accepting the “evil” institution of slavery into the West.11 Long a proponent of the moderate “colonization” plan, Fletcher believed that while holding men in bondage was a horrible sin, the only lasting solution to slavery was to emancipate southern slaves and return them “to their native Africa,” where, under more Christian and civilized conditions, they would flourish. Advocates of colonization, like Fletcher, despite their antislavery convictions, sometimes held racist views, arguing that the movement of blacks was preferable to emancipation. As one prominent proponent of colonization put it, because of “unconquerable prejudice” by white Americans, free blacks would be better off emigrating to Africa.12

The presidential election of 1844 threw the volatile issue of slavery into bold relief, and Calvin found himself right in the thick of the conflict. Normally a Whig, he could not bring himself to support the party’s candidate, the slave-owning Kentuckian Henry Clay. And he certainly opposed the Democrat, James K. Polk, whose proslavery pro–Texas annexation stance he found loathsome. In Indianapolis, the contest became “exciting,” with occasional outbreaks of violence as each side conducted spirited torchlight marches. “All are in arms as to the coming contest,” Calvin observed. A Polk victory, he predicted, would only lead to anarchy and the immoral spread of slavery, while “capitalists & men of business, the moral & religious part of [the] community”—the men with whom Calvin clearly identified—would be defeated by “forregners who are ignorant of institutions & [represent] the insolent ignorant part of [the] community.” Given his antislavery leanings, Calvin found himself approached by supporters of a third party, the abolitionist Liberty Party, to help campaign for its presidential candidate, James Birney. A week before the election, Calvin met with Birney supporters—a coalition of Quakers, participants in the Underground Railroad, and roughly two hundred abolitionists—in nearby Hamilton County. Sympathetic with their goals—especially their fierce commitment to an immediate end to slavery—Calvin nonetheless remained reluctant to take such an active, public role in the election, especially since he wasn’t convinced that campaigning for the Liberty Party would produce anything other than an unwelcome result: a vote for Birney would simply steal votes from the Whigs, all but guaranteeing a victory for Polk and the Democratic Party. When some of the abolitionist activists tried to persuade Calvin that Birney’s candidacy harmed both major parties equally, Calvin was unmoved. “I could not open [their] eyes as to the imposition of Birney & other imposters to aid a party who avowed war with Mexico to get Texas,” he wrote in his diary.13

To make matters worse for many Whigs like Calvin Fletcher, the fast-growing immigrant population of mainly German and Irish settlers did not warm to the elite, heavily Protestant tone of the Whig Party. Indeed, like most Whigs, Calvin believed that immigrant voters, plied with liquor and politically inexperienced, would unthinkingly support the Democratic Party. On Election Day, Calvin observed, “the newly naturalized Germans rushed to the polls to vote the democratic ticket.” “The ignorance, the want of schools, the deficiency of men of integrity & intelligence,” he noted, “renders it almost unfit for self government.” On the evening of Election Day in Indianapolis, bonfires in the streets lit up the night air, while the political activists set off cannon fire. The next day the outcome had not been announced, but Calvin sensed defeat: “I prepare for the worst & suppose or rather prepare my mind to meet an event I have so much dreaded.” He was right to feel such apprehension: while Polk secured a narrow victory over Clay in the popular vote—with Birney receiving only a tiny fraction of support—all twelve of Indiana’s electoral votes went to Polk.14

Little did he know it, but Polk’s victory would coincide with a personal loss as well for Calvin. Around election time, Calvin received a letter from his son Elijah announcing that he had dropped out of Brown University. Wishing “to strike out . . . for himself” without putting his father to further expense, and apparently prompted in part by an upcoming poor grade report, Elijah traveled to Philadelphia to stay for a while with a former roommate of Cooley’s until he could determine his next move. Elijah’s sudden departure from college, Calvin declared, was “an act of disobedience which I can forgive as a parent” but which “cannot be blessed as it is against the holy commandments of God.” He was also deeply “melancholy” about the impact of Elijah’s decision on his brothers, as well as its implied judgment of Calvin and Sarah’s parenting values. “It has caused me to review my treatment to my children, my advise &c.,” he wrote. “I fear I may have committed errors & shall endeavor to revise my mode of treatment in some manner.” His biggest fear was that he had somehow failed to “subdue his [Elijah’s] temper sufficiently” and restrain Elijah’s “romantic notions & view of the world which I thought would wear off in proper time.” All this devastating personal news happened just as the “eastern mail” arrived bringing the official news that New York had gone for Polk. “This news disconcerted me . . . & I soon sat down,” he recorded. “The same mail brought the letter of E.’s departure from Providence. To both of these dispensations may I submit—one a private affliction & the other fraught with forebodings of national calamity.” Alone and ill-prepared, Elijah, Calvin feared, might now be driven “to do something immoral & wicked to get a living.” For his country, he sensed that “immoral & wicked” things were already afoot.15

By the spring, Elijah had reconsidered and returned to college, sparking new faith in his father for the boy’s future. But for the nation, in Calvin’s view, there was no such hope, especially when it came to slavery. When the House of Representatives admitted Texas into the Union on January 31, 1845, Calvin saw the moment as Judgment Day: “I fear it is to hasten the punishment for the national sins & the greatest is negro Slavery.” Although he tried to reconcile himself to the decision—such an expansion of the country would, after all, offer greater commercial potential—allowing slavery into Texas left him hopeless: “I shudder at the consequences yet God may intend to punish us on the one hand & relieve these poor creatures on the other.”16

Soon Calvin began to take issue with respected religious institutions that were backing away from the slavery issue. He and his banking colleague, J. M. Ray, became disturbed when Presbyterians meeting in Cincinnati in May refused to support the numerous antislavery petitions that were put forward and instead “virtually accepted slavery as a legitimate Christian institution.” Calvin told Ray, “I could not cooperate with any denomination” that “[sanctions holding] millions of human beings in bondage & make[s] it a penitentiary offense to learn them to read the bible.” The slave question also provoked a rupture among the Methodists, prompting additional anxiety in Calvin. “The subject is now being agitated in the various churches,” he wrote, “& I think will result in a final separation of all the churches north & south.”17

In the midst of Calvin’s anger and fear over the direction the slaveholding American nation was heading, his personal world received another sudden, if not unexpected, jolt: Lucy Keyes Fletcher, his beloved eighty-year-old mother, died at the family home in Ludlow, Vermont. She was, Calvin observed, “worn out of old age.” Several years before Lucy’s death, her son Elijah reported to Calvin her declining mental faculties, writing, “Her memory [is] gone and quite childish.” Their brother Timothy, who had visited Lucy that same summer, found her condition “quite melancholy,” observing, “I hoped once more to have seen her with her original vigor of mind, and not as a second child.” Upon her death in the spring of 1846, Calvin remembered Lucy as small but “very shrewd, enterprising.” That last word meant a lot to Calvin, as he firmly located the roots of his own independent, ambitious spirit in his mother. She had, he proudly observed, a “most unbounded confidence in her children provided they would leave their native town & go ahead & especially if they would compete for places of honor & an independent fortune . . . Such was the confidence in the success of her children she urged her last son the 15th child & only one left at home to go out & compete for the honors which lay before the bold & enterprising.”18

Brother Elijah joined in the mourning, noting that “while I live [I] shall remember it with a sorrow that cannot be soothed.” Ever the distant caretaker of the family home in Vermont, Elijah promised to keep “our mother’s wardrobe carefully preserved” and to distribute it to all the living sisters and daughters. The furniture, he said, would be untouched, and the farm “should be the common home of us all or our children. No money can purchase it and all propositions to purchase from Friends or enemy will be promptly rejected.”19

Perhaps in response to his mother’s death, Elijah began making plans for his own final days. He told his children that summer that he had picked out his burial ground and gravestone. It was to be on the round top of a prominent hill near his Sweet Briar plantation. Elijah told Sidney that he wanted “a plain White marble obelisk 20 feet high,” enclosed with fine cultivated trees, shrubs, and flowers. Furthermore, he ordered, “All my children should meet there once a year and prune and trim and cultivate it.” Aware that for a vigorous fifty-six-year-old man such a preoccupation might seem strange, Elijah could only say that he contemplated death and his legacy “with pleasure.” “I meditate upon those events,” he told Calvin, “as composedly as my daily occupations[;] having lived a blameless life with the best intentions, the future has no dread to me.”20

If Elijah mourned his mother and pondered his own legacy, Calvin had neither the time nor the inclination to plan his final days. Instead, he found himself drawn quickly back into the public arena, repeatedly confronted with issues dear to his heart and the nation at large. Having already lent his support to the abolitionist cause, especially in urging protection for editors of abolitionist newspapers, who were increasingly under attack from proslavery mobs, Calvin joined hands with ministers who were willing to preach openly against the sin of slavery. His good friend, the prominent minister and activist Henry Ward Beecher, who pastored the New School Second Presbyterian Church in Indianapolis, overcame Calvin’s initial hesitancy about speaking out on slavery. With Calvin and a prominent U.S. circuit court judge listening from the pews, Beecher forcefully declared slavery a sin and warned against the looming American aggression in Mexico as an act of dangerous arrogance. After the sermon, as Calvin and other antislavery supporters had feared, several church members asked for letters of dismissal against Beecher. With such division in the church and Beecher’s own mounting personal debt, he soon sought out another opportunity and the next year took a position as minister in the Plymouth Congregational Church in Brooklyn, New York.21

The annexation of Texas not only prompted fears about the expansion of slavery, but also sparked a war with Mexico, which saw the annexation as a completely invalid power grab by the American government of territory Mexico viewed as its own. President Polk’s claim of the southernmost Rio Grande boundary in 1845 in effect provoked the dispute with Mexico. In July 1845, Polk ordered General Zachary Taylor to Texas; by the fall some thirty-five hundred U.S. soldiers had assembled on the Nueces River, prepared to take the disputed territory by force. Immersed for months in the newspaper accounts of this mounting threat in Texas, Calvin worried that “our nation are aggressors.” Like most antislavery activists in the North, he was firmly convinced that behind the aggression in Mexico lay the relentless drive of southern slaveholders to acquire new territory under the guise of “Manifest Destiny,” the notion made popular by the 1840s that Americans had a Providential mission to expand their democratic institutions across the breadth of North America.22

As with the Polk victory in 1844, the developing Mexican War took a personal turn for Calvin—and once again, it involved his son Elijah. After returning to college for a year, Elijah announced late in May 1846 that he was leaving for the “Far West,” heading for Missouri, where, as Calvin put it, he would “enter the broad world.” Despite being offered opportunities to study law; clerk in a mercantile store, like his younger brother Calvin; or work on the family farm, Elijah “could not bring his mind to settle on any of them.”23 “He is the first child I have had leave me to enter the world without my care & means of support,” Calvin noted. “It is not small matter for a young man of 22 to commence for himself as he now does.” Eventually, Elijah received the blessing of both his mother and his father before departing home on June 1, 1846. He journeyed first to Independence, Missouri, where he was able to find work outfitting traders headed for Santa Fe and Mexico. Despite his dramatic leave-taking from the family home, Elijah held no hard feelings for his parents. In fact, as he wrote Calvin from Independence, he felt great affection for them. Acknowledging that he had often “committed many wrongs . . . been impudent to mother—and sometimes to you,” he observed, “I never received a reprimand from you.” Everything his father had done for him, Elijah realized, had been “dictated by feelings of love.” “Oh, father,” he wrote, “how many times I wanted to go to you and tell you all how I felt & pour out my whole soul to you and tell you every secret thought, and I was afraid of you (why I do not know), I was suspicious and above all a pride of heart would arise—and thus I continued to muse my own unhappiness.”24

Comforting to his father as those sentiments may have been, Elijah’s work and future prospects conjured up all kinds of concern. “I am going to Zacatecas [Mexico] with [Reuben] Gentry, a trader and a gentleman,” Elijah wrote Calvin in June 1846. “I am to drive a carriage and will not be back for one year at shortest. I shall then likely return home & see you if I live.”25 Needless to say, such uncertainty about their son’s welfare produced anxiety in the Fletcher household. After weeks of no correspondence, Elijah made contact once again with his family in early July, assuaging some of their parental fears. “I felt much concerned about him,” Calvin revealed in his diary, “but am somewhat relieved by this letter.” Later that day, Calvin learned from his son Miles, who had just received a letter from Elijah, that Elijah had visited Fort Leavenworth and was helping outfit some of the new recruits bound for California and Santa Fe—both battlegrounds in the Mexican conflict. Predictably, Elijah’s deepening involvement in the developing war with Mexico only added to his father’s apprehension: “If he goes to Mexico at this period,” Calvin noted, “I think he goes into danger as the war renders the 2 nations hostile.” Into the fall of 1846, Calvin and Sarah grew increasingly worried as news emerged about General Taylor’s bloody battle in Monterrey. Not having heard from Elijah in six weeks, Calvin reported, “We fear for Elijah . . . who is now on his way to Zacatecas & think probably his safety may be effected by this battle.” Two weeks later, Elijah wrote his parents with news that he was suffering from dysentery and, more concerning, offered bloody depictions of what he had been witnessing. The morning he wrote, he told his parents, “a Spaniard died. They scooped out a hole of sand & laid him in.” Calvin feared his son would be caught up in a war that “seems to rage with Mexico with greater intensity & its settlement is uncertain. E. will be surrounded with a rough population.”26

By the spring of 1847, Elijah’s situation had grown even more precarious. The traders he had traveled with were caught up in a violent insurrection at Taos that led to the massacre of the territorial governor. Ten days later rumors swirled in the American press that General Taylor had fought a “severe battle with Mexicans” near Buena Vista in northern Mexico. Some 267 American officers and soldiers were killed, and nearly twice as many Mexicans died in the battle, a pivotal, hard-earned victory for Taylor.27 Because initial stories in the American press claimed that over two thousand Americans had died, Calvin called the battle “the greatest Slaughter that has ever occurred in any engagement where the Anglo Americans have been engaged.” “I moan this bloodshed—This inhumanity of man to man,” he lamented. “I trust it is mere rumor.” From Lynchburg, Calvin’s brother Elijah expressed alarm as well for the safety of his nephew and namesake. “I have felt no little uneasiness about your son in Mexico,” Elijah wrote Calvin, “and it would give me great pleasure to hear of his safe return to the bosom of his Family and Friends.”28

Elijah’s safe return would not come easy. He found himself in Zacatecas “surrounded with hostile Mexicans” fresh from the blood-stained battle of Buena Vista. His boss, Reuben Gentry, was taken prisoner along the road between El Paso and Chihuahua. Pretending he was a subject of Great Britain, Elijah managed to avoid capture. Upon learning of his son’s clever and possibly life-saving subterfuge, Calvin was at first upset: “I think it wrong & to me it forbodes evil & they must if detected be counted as spies. I do not wish my children except in an extreme case to be placed in such a condition.” Calvin eventually tempered his criticism, calling his son’s escape “almost miraculous” and applauding how he had “maintained his integrity in the midst of corruption.” On July 26, 1847, Elijah’s—and the family’s—drama finally ended: “This eve as we were eating supper E. arrived—[he] looked well,” Calvin reported in his diary. “It should be a matter of rejoicing & gratitude to God that he has been brought home.” It had been fourteen months since Elijah had left his home in Indianapolis—“and these months,” he accurately observed, “were the most perilous and eventful of my life.”29

Amid the trauma and uncertainty of Elijah’s exploits out west, Calvin had to say goodbye to his eighteen-year-old son Miles, who, like his older brothers, had decided to try his hand at college back east. Ironically, Calvin sought to discourage the boy from attending college, believing that he had proven his worth in helping out on the family farm, where he was greatly needed. Calvin even enlisted his son Calvin Jr. to keep Miles at home, but the effort backfired. Calvin Jr. instead wrote his father that Miles had “done more than any of us to help you, and did it cheerfully too, and has recd. less reward . . . If I am not much mistaken it is your desire to help us equally, on that score it is his turn to come.”30 Several weeks later, Miles was packed up and ready to go. Calvin and Sarah accepted the departure with a measure of sadness and hope. “We regret to part with him,” Calvin noted. “He has been a reasonably good boy. What he knows he knows well.” All the Fletcher children sent farewell gifts along with Miles—from nine-year-old Billy, “a half dime”; from six-year-old Stephen Keyes, some “dried cherrys”; and from everyone “an apple a piece.” Sarah gave him “a can of honey.” Their goodbye scene, as Calvin recalled it, was both muted and moving: “We conducted Miles to the gate & the children parted with him & I rode to town, shook hands & left him. I paid his passage, $13 to Wheeling. I trust his life may be precious in the sight of the Lord. I cannot preserve my children when with me but God has been good & gracious in this matter when they were present & absent.”31 Upon arriving in Providence, young Miles remembered the sad farewell, whose formality had betrayed a suppressed affection. “I felt very bad on leaving home,” he wrote. “I could hardly bear to shake hands with mother but the time had come and I had to go.” For Calvin, the weight of so much leave-taking in his family had sunk in: “I feel lonesome as Miles, Calvin, Elijah & Cooley, my four oldest have all left me for the present.”32

He may have felt lonesome, but he was hardly lethargic. Living a life forged on the anvil of self-improvement while supporting such a large family and trying to remake the larger world according to his own values made Calvin Fletcher a very busy man. As the presidential election of 1848 approached, he made a firm commitment to support the antislavery Free Soil Party, and its candidate, Martin Van Buren, the former president. He did so because he thought it “the right side of the question to vote against extending” slavery into any new territories. “I have examined the question in reference to my duty as a freeman & Christian,” he noted, “& I have come to the firm conclusion never to countenance slavery in any shape.” Calvin continued to claim that he preferred not to “meddle with public matters,” but when it came to slavery, it was “a matter of sheer duty & necessity. The good sense of the community have determined that not another inch of free territory shall be made slave domain.” Congress, he believed, should act “to exclude this curse on our land.”33

Like his antislavery crusade, Calvin’s fierce adoption of the temperance movement represented a commingling of personal experiences and larger social values. A growing movement of mostly Protestant ministers and social reformers since the 1820s, the battle against alcohol was waged by more than eight thousand local groups with well over a million followers by 1840. Calvin’s personal connection to the temperance movement began when he worked at a small tavern as a young man in Urbana, Ohio, shortly after leaving his Vermont home in 1817. Several thousand soldiers recently discharged from the War of 1812 lived in the area, and he saw firsthand what alcohol did to them. “I was then acting in the humble capacity of barkeeper at a little tavern & can say that scarcely without exception every man would get drunk & the last pay they drew was used in dissipation,” he later remembered. “They soon scattered & died & scarcely one returned to the useful departments of life.”34

Active in the movement from the late 1830s on, Calvin became a prominent spokesman for the temperance cause by the mid-1840s. Written off at first as “a humbug farce,” his temperance advocacy soon enlisted the support of several Indianapolis businessmen, and in June 1845 he was asked to deliver a major address to the Noblesville branch of the Indiana Temperance Society. His opening declaration was nothing less than a personal credo: “Life,” he said, “is a scene of difficulty, perplexity, anxiety, a warfare which demands the use of the best faculties with which man has been endowed. To lose one of our senses, seeing, hearing, tasting, feeling, smelling, is esteemed a great misfortune. Also to lose any faculty calculated to destroy the moral sense, the ability to compare good with bad . . . would be truly deplorable & anything we do to lessen the availability” of those senses “may be called intemperance.” His message was clearly aimed at youth. Young people, he believed, unthinkingly expect a long life “full of enjoyments.” But that leaves them ill prepared for the real, and mostly difficult, journey that lies ahead. Not only can unforeseen financial problems or sudden illness shorten a life, the “useless frivolous pursuits” that “so often captivate the young” prompt imprudent choices: “See the circus rider, the play actor, the horse race, the fiddler for the menagerie, the gambler,” Calvin exhorted the crowd. “They seldom live out half their days . . . No, they seldom pass 35 or 40 & then come to some violent end & rarely leave any one who will own them. Their whole history is summed up in this—They have led intemperative lives.” In Calvin’s perspective, anyone who gave in to habitual anger, revenge, or deceit lost all ability to reason—and these flaws “are weaknesses as much as getting drunk.”35

While he pushed for local and state laws prohibiting the sale of alcohol, Calvin tried to enforce within his own family the same sort of broadly conceived temperance spirit regarding all forms of excess. When Jonathan Harrington Greene, a renowned former professional gambler from Cincinnati, came to Indianapolis with a powerful anti-gambling presentation, Calvin attended the event with his oldest son Cooley. “Green the Gambler” made a big impression on them, so much so that Calvin was prompted to challenge his four oldest sons to sign a pledge never to play cards “either for amusement or for gain.” Away at Brown University, both Miles and Calvin Jr. responded respectfully but warily: “Now for my part I do not know one card from another,” Calvin Jr. wrote his father. Plus, he couldn’t imagine that if his principled life and common sense hadn’t kept him from learning to play cards, “no promise could.”36 Signing such a pledge, he argued, would make him feel obliged to list “every vice, every kind of folly and extravagance, and everything that is forbidden by my duty to God and man.” Assuring his father that nothing in his response “is intended as impudence,” he questioned the entire notion of the pledge, at least as it related to him. “I hoped that all these things were tacitly understood e’er I moved one inch from home, at least I supposed they were, and cannot bring myself to think . . . you do not now have confidence in me,” he wrote. Not wanting to appear disrespectful, Calvin Jr. a few weeks later agreed that he and his brother Miles would sign a pledge, noting, “It may not be worded to suit you, but it is all that I think necessary.” The wording was simple: “Neither of us ever intend to play cards. Calvin Fletcher, Jr., Miles J. Fletcher.”37

While only partly successful with his own family, Calvin tirelessly devoted himself to stamping out gambling, drinking, and “houses of ill fame.” He spoke at public meetings aimed at suppressing gambling and offered up resolutions, most of which were swiftly adopted. In one meeting, twenty or thirty “gamblers & their adherents” showed up to make a noisy protest but found themselves in uncongenial company and “were soon silenced.” At the courthouse a temperance group met by candlelight in December 1846 to battle what they called the “vicious,” a group Calvin labeled the “disaffected [and] the ignorant” who were “opposed to good order.” Ten citizens gathered that evening at the Hall of the Sons of Temperance and unanimously passed resolutions to suppress all gambling, drinking, and prostitution in the community.38

Even if he had strong fellow activists who supported his temperance cause, Calvin experienced significant pushback from within the community against his zealous crusade. His side (“the moral part of the community,” as he put it) lost several votes over the question of selling liquor to the “wicked.” He knew he was “marked for the vengeance of those who hated order,” and, in fact, in one memorable election in 1847 he became the subject of ridicule for his “anti-Gambling exertions,” with the result that the “wicked” voted him in as “fence viewer.” This position, whose job it was to assess damages when livestock broke into another person’s property, was clearly seen as the most tedious, least important local office. “I will perform the office cheerfully,” Calvin noted solemnly in his journal.39

More hurtful was his own brother’s reaction to Calvin’s relentless temperance activities. A few years later Elijah reported to Calvin the fanatical efforts of the “Temperance Friends” in Lynchburg, Virginia, and their “warfare upon all the local authorities that did not favor their views,” including a demonstration to unseat all the civil officials who favored granting licenses to taverns for selling liquor. As it happened, Timothy Fletcher, a brother of Elijah and Calvin who also lived in Lynchburg, was one of those officials the temperance demonstrators were protesting. But, Elijah noted, “as it was thought they [the temperance protestors] were rather stepping out of their sphere and carrying the matter too far, a reaction took place,” and Timothy won reelection to the magistracy by an overwhelming vote. “Thank you for making Timothy so happy,” Elijah concluded. Probably more disturbing to Calvin was Elijah’s description of his “charitable Hobbies—Religion, Temperance, Abolitionism, Education,” which, he noted, were “all most praiseworthy and commendable.” Calvin took exception to the word “hobbies” and was particularly defensive about his abolitionist zeal, arguing that he was simply engaging in “moral suasion with the old Slave states till they may either voluntarily manumit their slaves or some amendment by the Constitution to release them.”40

Elijah’s humorous dismissal of his brother’s “hobbies” reveals as much about his own detached, laissez-faire worldview as it does about Calvin’s reforming zeal. And Elijah was keenly aware of the differences in how the two men spent their time in public versus private arenas. “You are probably by nature more social and not altogether of that retiring turn,” Elijah observed.

You have from an early period mixed busily in the varied active pursuits of life, always having many warm, attached friends, and promoted to stations of honor and trust . . . You are constituted with a zeal for the welfare of mankind that renders you peculiarly fitted for public employment. You have gifts . . . I have not gifts that would make me useful in many things like yourself. I was destined for an unobtrusive, retired life, the sphere of my usefulness to be more limited than yours.41

There certainly seemed no limit to Calvin’s reform instinct. Given the pivotal importance of education for the entire Fletcher family, it is perhaps unsurprising that Calvin also embraced the common school movement with so much determination. Less controversial than temperance and abolitionism, the common school movement came wrapped in a spirit of economic vitality and community improvement. “Can there be a question of greater, or more vital importance to the prosperity of our State?” Calvin asked in an op-ed piece published in May 1848. The push for free and better schools, he argued, should appeal to “the intelligence, the philanthropy, and patriotism of the Press of Indiana.” By voting for “Free Schools,” Calvin insisted, “you will elevate the character of our State, and thousands yet to be, will bless your memory.”42

By the mid-1840s, Calvin had become a complete convert to the educational reform movement, initiated a decade earlier under the leadership of Horace Mann, which focused on bringing local school districts under a more centralized town authority and making school attendance mandatory, curricula uniform, and teacher training more professional. Backed mostly by evangelical Protestant reformers like Mann, the common school movement emerged in part as a reaction against increased Catholic immigration and the desire to prevent Catholic schools from receiving tax money. While Calvin certainly bought into the anti-Catholic, anti-immigrant elements of the movement, he was mostly focused on the need to bring good, qualified teachers out West to places like Indianapolis.

The city had been growing quickly, providing opportunity and profit for those in banking and government, especially after 1825, when the state’s capital moved to Indianapolis from Corydon. As early as 1835 Calvin adopted the town’s boosterism, confiding in his diary, “The past seems a dream, a delusion. I have witnessed a total wilderness converted into a flourishing city.” Calvin was thirty-seven, and Indianapolis, only fifteen years old itself, had grown to about seventeen hundred people. By 1840 it was one of a few real urban centers in Indiana, with a population over three thousand. And its growth would continue: by 1850 over eight thousand people lived in Indianapolis.43

The city may have enjoyed a thriving population, but it certainly wasn’t showcasing the kind of educational achievement that Calvin and other civic leaders felt a progressive city required. In 1840 one in seven Indianapolis citizens couldn’t read, and by 1850 that level of illiteracy had risen to one in five. In some southern counties (Jackson, Martin, Clay, and Dubois), barely half the population was literate, and only one in three children in the state attended school. Indianapolis didn’t establish a free public school until 1853.

Such circumstances of a growing but barely literate population prompted educational reform in progressive thinkers like Calvin. He was particularly enamored with the plan of former Vermont governor William Slade, who visited Cincinnati in 1846 in order to set up an organization to send “properly qualified teachers,” all of whom were women trained in New England teachers’ colleges (“normal schools”), to schools in the West. When the Indiana legislature called for a convention to be held in Indianapolis in May 1847 aimed at promoting common school education, Calvin chaired the organizing committee. Governor Slade addressed the group, Calvin proudly recalled, declaring that “our highest priority as a nation” depended “upon the intellectual and moral elevation of the masses of the people, and . . . the importance of a good common school system in order to attain this important object.”44

Author and reformer Catherine Beecher joined Slade in proposing that six or eight female teachers be sent out to Indiana. Calvin eagerly welcomed the idea, agreeing to temporarily take one such female teacher into his own family—room and board being their only form of payment. In the summer of 1847 the first crop of transplanted New England teachers arrived in Indiana. Early one morning in June, Calvin, along with other key members of the common school organizing committee, met the “9 young ladies” at the Palmer House in Indianapolis. They were mostly Baptist and Methodist women who had “voluntarily left their friends & relatives to become teachers in the West—not seeking compensation but to supply the destitute places [in] a state where at the present there will not be more than 5 out of 6 [who will] learn to read & write.”45 Samuel Merrill, a prominent civic leader and friend to Calvin, claimed the transplanted female teachers “are said to be accomplished and the prospects are that they will be well provided for first with schools and then with husbands.”46 One such teacher was Keziah Lister, an intelligent and lively thirty-year-old woman from Maine who quickly caught Calvin’s eye as a remarkably effective teacher and a clearly kindred spirit. He called her “an extraordinary woman” who could “more effectually win the hearts of her pupils than any one I ever saw . . . She seems to have been a God send & blessing to this place.”47

Despite considerable opposition to free public schools—voters were leery of the cost and the centralization of authority—Calvin overcame the resistance. In city elections in 1847 the voters approved a modest tax for the establishment of free schools, a major victory for Calvin and his fellow common school reformers. “I can leave no better inheritance to my children,” he later observed, “than a moral, intelligent, religious community & I cannot be an indifferent spectator to these matters & to the interests of this my adopted state.”48

If he was successful in bringing free, compulsory public schools to Indiana, Calvin faced a more daunting struggle when it came to influencing the educational and career goals of his own children. With his sixteen-year-old daughter Maria studying at a Providence, Rhode Island, prep school, his educational expectations, while modest, still mattered. But a report from her teacher, John Kingsbury, suggests that female education of the time aimed more at producing pleasing and obedient girls rather than fostering academically ambitious ones. Kingsbury told Calvin in the summer of 1849 that Maria’s progress was good, as she was “dutiful and obedient, respectful and desirous to please,” despite obvious “deficiencies in some of her elementary studies,” such as penmanship, spelling, and writing. Cooley visited his sister later that summer and reported to his father a similarly gendered appraisal: Maria, he observed, was now “wonderfully altered and much improved. She wears long dresses, looks and acts like a lady . . . She is much beloved.”49

When it came to his sons, Calvin sought to nurture a nuanced combination of high achievement and explicit devotion to improving themselves; his sons must pursue, he wrote them, “self education like their Father.” As much as Calvin pushed his children to commit themselves fully to their studies, he also felt curiously abandoned by his sons off at college, who were so caught up in their own worlds that they ignored his needs—in terms of both labor and personal attention—back home. While attending Brown University in 1847, Miles and Calvin Jr. felt compelled to respond to their father’s worry that they somehow intended to “desert” him. “Do you think we have no desire to aid you?” Miles wrote. “Do you think we would spend the money so hard earned by you without repaying your kindness? By no means.”50 As he often did, Calvin wanted his sons to work tirelessly at their studies and yet wondered if such a devotion to college also betrayed an effeminate temperament, compared to that cultivated by the manlier world of farmwork. Caught between the plowboy life in which he was raised—and which he still revered—and the educated world he came to admire, Calvin sent mixed messages to his sons at college, especially as he was missing their company and their labor at home.

He was even willing to shame them into accepting his perspective on school versus work. Calvin Jr. essentially caved to his father’s plea to return from college and work at home: “You say, ‘my sons do not seem to have courage to get a self education like their Father, and if I can indulge them otherwise I shall,’” Calvin Jr. wrote his father in September 1847. “Now Father, I don’t know whether you think I have any pride or feeling. When I read that sentence I feel ashamed of my self to think that I have been here 18 months. I abhor the idea and detest the place. I have no desire for study no pleasure in any thing.” Frustrated at the cost of funding the college education of so many sons, Calvin wanted to ensure that Miles and Calvin Jr. completed their schooling before, he wrote, “I ever send another child from my house to get an education.” To that statement, Calvin Jr. took exception, forcefully criticizing his father for implying that he and his brother Miles might be robbing their younger siblings of a good education:

Now Father it is wrong—criminal in me to stay one day here and have my brothers and sisters deprived of the advantages I enjoy . . . Never shall a brother say to me, “You, sir, were the cause of my being an ignoramus—of my being deprived of going to college.” . . . I have already had my share and am now ready to give place to them, and am at your service at any moment. My chief desire in this life [is] to assist you, to help educate the younger members of the family.51

His brother Miles took on the “effeminate” charge directly. “You say that the boy in the plough patch,” Miles wrote, “who could neither read nor write but could water a hundred cattle and take care of as many hogs was worth a hundred boys who had become effeminate by a collegiate course of four years. What encouragement then is there for me if at the end of my college course I shall be worth only one hundredth part as much as I was when I lived in the plough patch?” Far from wanting to come home simply out of duty, Miles had something to prove to his father: “I shall dig on and show you that at the end of four years I have not become effeminate but that I can do anything you please to set me at.”52

For other young men in this era, the impulse to prove their manliness found expression in movement and adventure. After the discovery of gold nuggets in the Sacramento Valley in early 1848, the California gold rush of 1849 sparked a huge movement mostly made up of men dreaming of wealth. Once the news of the discovery spread, thousands of prospective gold miners journeyed to San Francisco and the nearby area in search of gold, spiking the nonnative population of the California Territory from about one thousand before 1848 to over one hundred thousand by the end of 1849.53

In this powerful public event, Calvin Fletcher insisted on having no role. Even though he himself had sought a new life and followed his dreams by leaving home for the West, the allure of California and gold was nothing but a chimera to him. “The California Gold has no little attraction,” he declared on Christmas Day 1848. Even though he knew many young people in Indianapolis who seemed “determined to start for that country,” Calvin disapproved of their aim. “I think those who go must spend their lives in bad company,” he maintained, and instead of finding wealth, “the greater proportion must live in poverty.” It was the hard-working farmer and mechanical laborer, he believed, who “will get the gold.” Digging for gold, he insisted, “has but little attraction to the honest laborer generally.”54

But there was nothing false about the allure of the California gold rush to the sons of Calvin’s brother Elijah. In June 1849, Elijah reported that Sidney and Lucian had gone to California, one via the Gulf of Mexico and Panama and the other around Cape Horn. “Sidney always seemed anxious to travel and explore the Western part of our Continent and the excitement in California hastened the undertaking,” Elijah told Calvin. “Lucian has gone as a real gold Hunter, joining a Company in Richmond who bought a fine Vessel and freighted her, starting from The Capes of Virginia 1st of April.” Elijah lamented the decision, at least Sidney’s, to head west, writing, “I regretted somewhat Sidney’s departure, for he was a man of business and much assistance to me. But like you, I let them when arriving at years of discretion carve out their own destiny.” Calvin, however, saw nothing promising about his nephews’ westward wanderlust. “I think this is a doubtful expedition,” Calvin noted in his diary. “I fear they will never return to him. He has but 2 sons & at the age of 60 to have them leave him with all his cares seems hard. But so it is. There seems to be stirring incidents going on in the old world.”55

Predictably, Sidney returned quickly from the gold rush, coming home at the end of 1849 after three months of very modest earnings from the gold mines. While in California, according to his father, he had “endured much hardship, seen much of the world and returned better contented, perhaps, with a comfortable home.” Sidney concluded that northern California could never be a “desirable Agricultural country” owing to its limited rain. He returned in good health, but, Elijah conceded, “the hardships he has undergone make him look much wasted.” Thankfully, his father noted, Sidney was now “devoted to his Farm, the only place where he is happy and contented.”56

Lucian, also predictably, stayed behind, determined to dig until he got rich, despite encountering hardship and sickness. Like so many others, he failed to make any money in the mines; after a few months, he relocated to Stockton, California, where he intermittently practiced law. His occasional letters home mentioned his desire to return to Virginia. Lucian’s failure in the gold fields was both a personal tragedy and a common occurrence among western adventurers. As Elijah observed, “few of our Californians have returned lately but none that have gone from this part of the country have met with much success.” Finally, in early November 1851, Lucian made his way home after being detained in Panama with a debilitating “Fever.” He “has been much of his time indisposed since reaching home,” Elijah observed. Lucian’s western adventure would not be his last one, and it signaled the beginning of a father–son estrangement that would not end happily.57

Tusculum, Elijah Fletcher’s Lynchburg home

All of these events only strengthened Elijah’s resolve to focus on his more successful and obedient children while cultivating his pastoral retreat at Sweet Briar. He gave Sidney the Tusculum plantation that had come to him from the heirs of William Crawford, his father-in-law. Elijah was clearly pleased that Sidney was now devoting himself to managing the plantation. “Farming is the only vocation in life that pleases him or which nature seemed to adapt his taste,” he wrote his brother Calvin. And Elijah fairly delighted in regaling family members about the wonderful trips his daughters frequently made to New York City, where they picked up fashionable furnishings for their Sweet Briar home back in Virginia. They especially enjoyed visiting family in Ludlow. “They are all Fletcher,” Elijah proudly noted, “charmed with the Old Farm in Vermont, as well as all our Family, and they possess not a particle of the foolish southern prejudice against Northern people and Northern habits.”58

Like their brothers, Indiana and Betty also thought of adventuring west, but only in the context of touring or visiting, as they always needed a “gallant,” a male chaperone, to accompany them. In the fall of 1848, Elijah reported that the two girls were planning a winter trip, accompanied by Sidney, either out West or to Cuba, New Orleans, and then back home via Charleston. Elijah saw travel not only as a broadening experience but also as a welcome opportunity to visit far-flung family. “My Daughters,” he noted, “have often told me that they value their [travel] opportunities far above any wealth I could bestow upon them.” Thus Elijah felt especially neglected when it came to getting to know Calvin’s children, particularly when the oldest child, Cooley, in 1849 planned a “sojourn” (actually foreign mission work) in Switzerland but made no plans to stop in Virginia. “Can not Cooley make me a visit before leaving America?” Elijah asked his brother. “It seems strange that I should never have had the opportunity of seeing any of your Children, though you have many times promised me a visit from some of them.”59

Elijah himself preferred the quiet and solitude of life at Sweet Briar, while his wife Maria mostly managed the house in Lynchburg, but he also enjoyed taking the entire family to reunions in Vermont. These journeys became much easier with train and steamboat travel. Before that, it could take several weeks to get from southwest Virginia to the Fletcher “mansion” in Ludlow, Vermont. With a strong horse, good weather, and the best of roads, it took four to six days to travel just from New York to Boston. But by the 1840s and early 1850s more than thirty-seven miles of turnpikes, or toll roads, had been built in New England. Furthermore, these new roads were far better constructed and maintained than earlier roads, allowing faster travel. Stagecoach lines now stretched across the Northeast, with fresh horses spaced out every forty miles or so. Steamboats created much faster passenger travel on the rivers, along with carrying enormous amounts of cargo upstream. Finally, after 1830, the railroad dramatically sped up travel. In good weather, with well-rested horses, a stagecoach could perhaps travel at eight or nine miles per hour. The small locomotives of the 1830s traveled at twice that speed. And by the 1840s, railroad tracks had spread throughout the most populated regions, especially the Northeast, greatly diminishing travel time. A trip from New York to Boston could now be accomplished in less than a day.

Even still, there were surprises and scares. When Elijah and his family returned home from one such reunion in August 1852, he promptly wrote a detailed report on that same trip home to Calvin, because he knew his brother and others “might feel some little anxiety to know how we fared on our way home,” having no doubt read in the papers about a major disaster involving the steamboat, the Henry Clay, on which they had traveled part of the way. Launched in August 1851, the Henry Clay was a side paddlewheel steamboat that ran between Albany and New York City. Elijah and family boarded the vessel at Albany on July 28, 1852, on their way home from the reunion. Just before 3 p.m., as the Henry Clay neared Yonkers, New York, a fire broke out onboard, quickly engulfing the midsection. The pilot immediately turned the burning ship—with five hundred passengers aboard—eastward to reach the nearest shore, a mile away. It crashed into the sands at Riverdale, New York. Some passengers at the front of the boat were able to jump to the shore, but those at the back were trapped by the raging fire in the boat’s midsection and either were burned to death or drowned. All told, some seventy-two people were killed in one of the era’s most notorious steamboat disasters.60

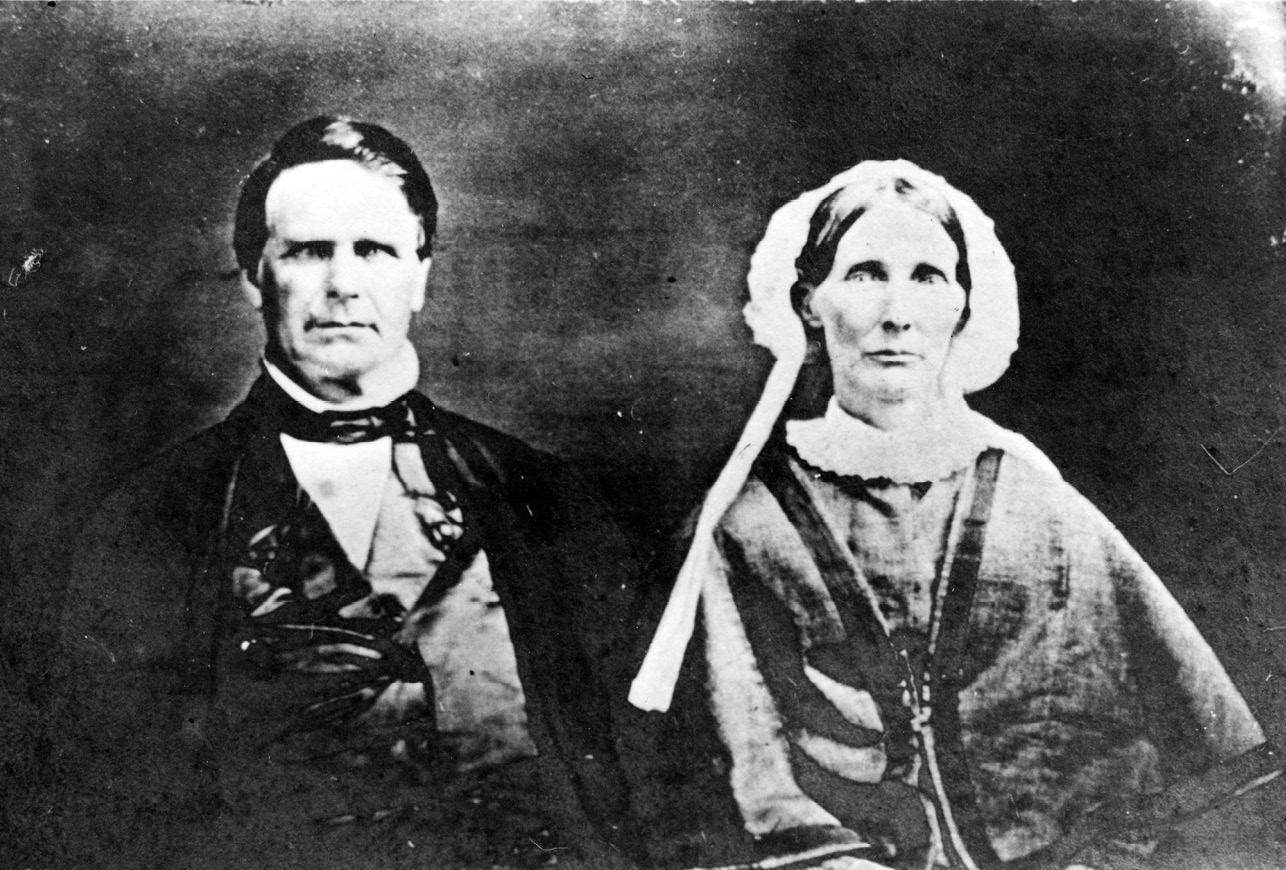

Calvin and Sarah Fletcher, 1844

If travel helped bring the Fletcher family closer together, regular, thoughtful correspondence was the true adhesive. Both Calvin and Sarah insisted on their children writing letters to family members when away from home. For Sarah, writing to her children and expecting letters back helped inculcate virtue, discipline, and morality. While away for health reasons in Onondaga, New York, on Lake Superior in the summer of 1853, Sarah wrote to two of her sons, Stoughton, twenty-two, and Billy, sixteen, who were in need of counseling on the essence of a “virtuous man.” “If a man,” she wrote, “has acquired great power and riches by falsehood, injustice, and oppression, he cannot enjoy them, because his conscience will torment him, and constantly reproach him with the means by which he got them. The stings of his conscience will not even let him sleep quietly, he will dream of his crimes; and in the day-time, when alone, and when he has time to think, he will be uneasy, he is afraid of everything.” A virtuous man, even if poor, will have his virtue “as its own reward,” which always serves as a “comfort.” Sarah directed this message especially at Billy, who had been struggling with volatile teenage emotions and an uncertain sense of self. “Billy,” she wrote, “I want you to stick to your virtue & religion.” And she wanted him, too, to write her thoughtful letters from the heart. Very few of Sarah’s friends and acquaintances staying in the area, she told the boys, had received any letters from friends, despite being “very anxious to hear from home. [And] they are perfectly astonished at the number of letters I have received & written.” In an accurate and revealing comment, she declared: “I tell them we are a writing family & believe in keeping up a correspondence with each other.”61

But when ill health hit, communication necessarily slowed down as family members had to focus on the stricken individual and, all too often, on the mourning of immediate family. Frequently, it would take weeks, and sometimes months, after a painful loss for news of the death to be fully conveyed to loved ones elsewhere. That is how it happened for Elijah Fletcher and his family when, around September 1, 1853, Elijah’s wife, Maria, became very sick with a “bad Fever,” possibly typhoid, while vising her son Sidney at his Tusculum plantation near Lynchburg. Ten days later, on September 10, 1853, Maria died. As her nephew wrote, she was now gone “to her long home, never to return, and paid the debt we have all got to pay sooner or later.” Elijah couldn’t bring himself to discuss the death with his brother for nearly three months. “We have had mourning and affliction in our Family since I wrote you last,” he finally told Calvin. “Death has laid a heavy hand and made a great raid in our social circle, and though the lot of humanity, it is not the less distressing and grievous to lose one we have long been connected with in the joys as well as conflicts of life’s busy scenes.” Maria’s death devastated Indiana, reportedly to the point that she couldn’t speak of it for a great while.62

Illness—typhoid, cholera, and dysentery, among others—struck nineteenth-century families of all ranks and sometimes prompted unexpected loss. In the summer of 1854, Sarah traveled with Calvin to the Fletcher homestead at Ludlow for a family reunion. Most of their activities involved visiting, card-playing, strolls along familiar childhood paths, trips to the cemetery, and the careful avoidance (not always successful) of politics and religion. Soon after arriving in Ludlow, however, Calvin fell quite ill with “the desentary” and began taking “the naucious calomel” ordered by a local doctor. Afflicted with bloody discharges, he was slowly nursed back to health over the course of two weeks, thanks to Sarah’s round-the-clock care. “Mrs. F.,” he later noted, “watched me as if I were an infant . . . For several days I felt it was uncertain if I should recover.”63

Exhausted from the constant caregiving, Sarah tried to resume her burdensome household duties once they returned to Indianapolis on August 12. But a month later she fell ill. At first, Calvin was distracted, as he was once again caught up in volatile public issues. With the ongoing tension over slavery’s extension into the territories, Calvin and other antislavery activists looked to the Kansas Territory, working to ensure that “free soil” settlers would prevail in the region and prevent the evil institution of slavery from getting a foothold there. On Sunday, September 24, 1854, Calvin planned to go to the Second Presbyterian Church in Indianapolis to help take up a collection to build churches in the Kansas Territory. But the night before, at 1 a.m., Sarah awoke with “a violent pain in the abdomen” and thought it could be some uterine infection or inflammation of the bowels. It was almost certainly an acute bowel obstruction, most likely from colon cancer.64 Calvin called in their doctor, who seemed unsure how to assess her swollen abdomen. From the beginning, Sarah’s “great distress” made Calvin wonder if “her life was in danger,” and so he decided to stay home from church. That day the doctor came again and applied “a mustard poltice,” but she got no relief. “I spent the day with her,” Calvin noted in his diary, “& told her I feared her recovery doubtful.” Later the doctor gave her some morphine for the pain, which did help, but Calvin nonetheless alerted his children that the end might be coming, though he advised all to maintain “prayerful firmness.”65

Sarah struggled in and out of consciousness for a few more days. Then, just before dawn on September 27, she awoke from her stupor and Calvin decided to call in the children for a final farewell. “They all came round her bed,” he noted. “She shook hands with each & when she came to take Albert’s [hand she] seemed much agitated. He cried. She motioned him to be calm.” Only eight years old at the time, Albert had been taken out of school and had spent the previous two days of his mother’s rapid decline “terrified,” watching from the “vine-covered apple trees” just outside his mother’s windows. “I couldn’t understand that it was possible for her to be taken away,” he recalled years later.66

Sarah began vomiting large volumes of a liquid “resembling blue ink,” a sign of internal hemorrhaging, their doctor announced. Even near the end, Sarah “observed her accustomed neatness . . . even to the last moment she would & did make great exertion to prevent vomiting . . . or [spill] even a drop of water on the bed clothes.” Just as the clock struck six in evening, “she breathed her last just after the setting of a most beautiful sun of one of the most delightful days that ever shone,” Calvin noted. “Our house was thronged with the poor & rich who deeply sympathized with us in our loss, great loss.” Only Cooley and Elijah were absent—they were notified via telegraph the night of her death.67

“We all felt and looked like a shipwrecked band,” Albert remembered. “Mother was no longer there with her benign and worshipful and placid face. Her chair next to mine was vacant, and we sat around the dining room weeping. To me, and I think to all the children—the younger ones, the end of the world had come . . . Mother had gone and all future life [was] at a standstill and useless.” For Calvin, Sarah’s dignified death was instructive to them all: “We did not know how to live till she showed us how to die,” he wrote. According to Albert, Calvin gave a brief speech before his “stricken” family about “what Mother would have us do, the kind of lives she wanted us to live, and to become useful and helpful, courageous and true.” Calvin’s talk, Albert noted, forcefully reminded everyone of Sarah’s “rare character” and “roused us . . . from our dreamy despair.”68

None of the Fletcher children missed Sarah more than Albert. His observations in “Memories of My Mother,” composed just before his death in 1917, drew revealing contrasts between the parenting styles of Calvin and Sarah. According to Albert, “fear was constantly present when Father was near; and calmness, and a feeling of punctiliousness and caretaking was with me when Mother was directing me. Mother was so absolutely religious in all her doings and sayings . . . that whatever she did had to me a meaning of sanctity and devotion.” Albert remembered his father in a much starker light: “Father was stern and demanding, relentless in case of lapse from strict duty and behavior, and there was no Mother to intercede . . . Father made things move; he praised or blamed or punished but, with all his ability, he hadn’t the faculty of making the home happy.”69

* * *

Losing a beloved spouse pushed Elijah and Calvin in different directions. For Elijah, the “grevious” loss of Maria drove him even further into a life of retirement and solitude, sweetened only by the near-constant companionship of his devoted daughters, especially Indiana. But his contentious estrangement from Lucian made him more withdrawn. Never a man who loved the public arena, Elijah separated himself even further from political life after Maria’s passing. In contrast, when Sarah died, Calvin, if anything, responded with a fresh sense of urgency and activism. After a period of intense mourning, he became increasingly caught up in the difficult issues of the day—slavery, temperance, education—as well as the daily struggles of his many children. And then, in yet another example of the commingling of the public and the personal, Calvin found a remarkable teacher from the common school movement who renewed his hope in more ways than one.