Chapter 11

The Cooling System Up Close

In This Chapter

Looking at radiators and coolant recovery systems

Looking at radiators and coolant recovery systems

Shooting the breeze about the fan

Shooting the breeze about the fan

Understanding water pumps

Understanding water pumps

Talking about thermostats, heater cores, and transmission coolers

Talking about thermostats, heater cores, and transmission coolers

Airing the truth about air conditioners

Airing the truth about air conditioners

With all that air, fuel, and fire stuff going on in its engine, your vehicle needs something to help it keep a cool (cylinder) head! Because water is usually cheap, plentiful, and readily available, auto manufacturers have found it to be the simplest answer to the problem. A few have found that air is even cheaper and more abundant; they designed the air-cooled engines on the old Volkswagens, but aside from some VW bugs and air-cooled Porsches that are still on the road, there are few air-cooled vehicles available in the United States these days.

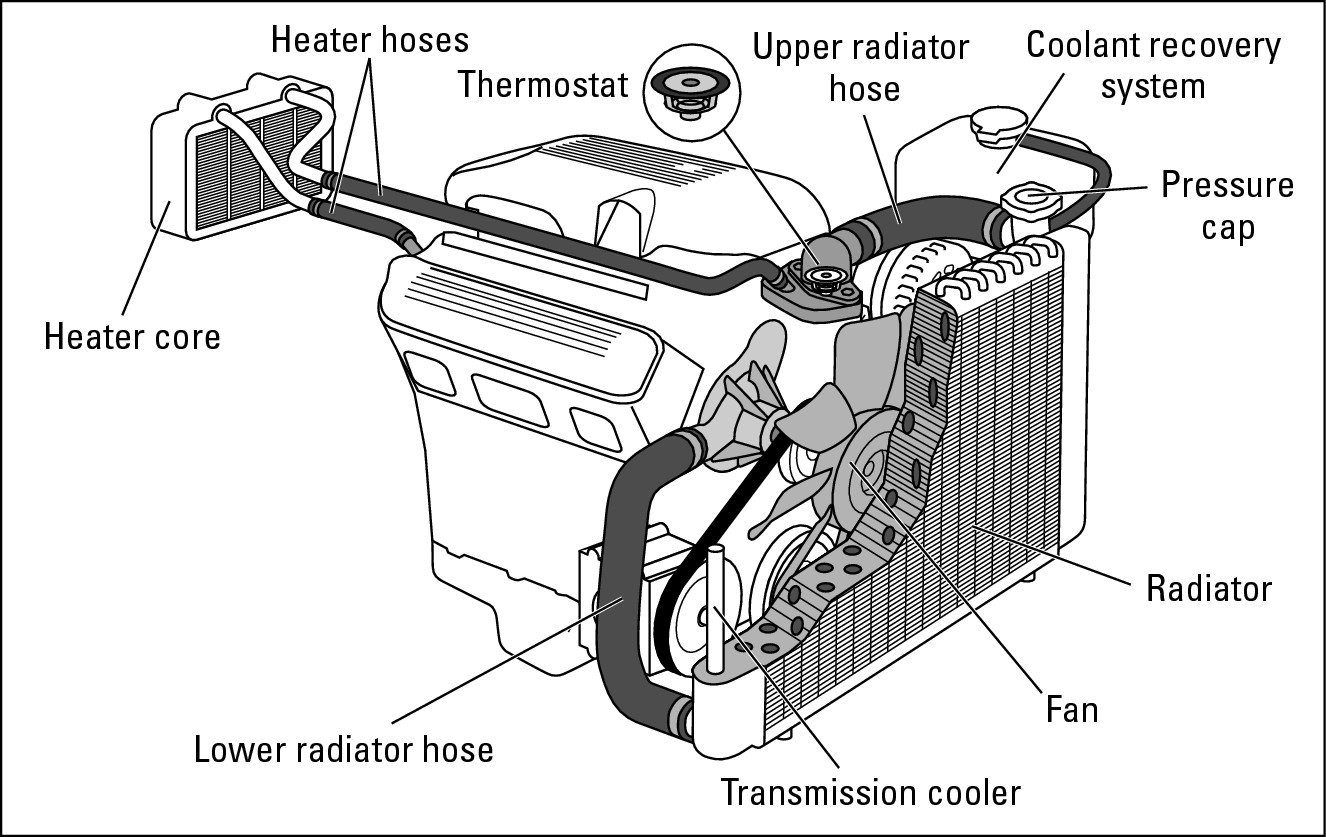

Of course, nothing is as simple as it seems. Automakers have added some gizmos to keep the water in the engine from boiling too easily: a water pump, fan, radiator, thermostat, and coolant. There’s also a transmission cooler to keep the transmission from overheating and an air-conditioner to keep you from overheating. Together they comprise your vehicle’s cooling system (see Figure 11-1).

The cooling system is highly efficient. It usually requires almost no work to keep it operating — just a watchful eye for leaks and an occasional check or change of coolant. Of course, some vehicles have more complicated systems or variations on the theme, but in general, if you understand the way the basic cooling system works, you should have little trouble dealing with the one in your vehicle. Whether you do the work yourself or have it done professionally, keeping the cooling system in good shape will go a long way toward “keeping your cool” when things heat up on the road.

|

Figure 11-1: The cooling system. |

|

This chapter explores the cooling system part by part. Chapter 12 shows you what to do if your vehicle overheats and how to maintain and troubleshoot the cooling system and make easy repairs. Chapter 21 helps you get out of trouble if your car overheats on the road.

Coolant/Antifreeze

To keep the water in the cooling system from boiling or freezing, the water is mixed with coolant or antifreeze. In the interest of brevity, I just call it “coolant” throughout this book.

Today’s engines require specially formulated coolants that are safe for aluminum components. There are long-life (sometimes called “extended life”) coolants with organic acid rust and corrosion inhibitors that promise to last for as long as five years. Automakers use some of these coolants as original fluid in new vehicle radiators made of aluminum (they can’t be used in anything except aluminum radiators).

.jpg)

The Radiator

When the fuel/air mixture is ignited in the cylinders, the temperature inside the engine can reach thousands of degrees Fahrenheit. It takes only half that heat to melt iron, and your engine would be a useless lump of metal in about 20 minutes if your vehicle couldn’t keep things cool. Naturally, the coolant (and water) that circulates from the radiator through the top radiator hose to the thermostat and around the cylinders in the engine block gets very hot, so it’s continually circulated back to the radiator via the bottom radiator hose, where it cools off before heading back to the scene of the action. The radiator’s pressure cap keeps your car from boiling over, and the coolant recovery system holds extra coolant so it doesn’t overflow onto the roadway.

The hoses

The radiator is designed to cool the liquid quickly by passing it over a large cooling surface. The liquid enters the radiator through the top radiator hose, which is usually connected to (you guessed it) the top of the radiator (refer to Figure 11-1). As the liquid descends, it runs through channels in the radiator that are cooled by air rushing in through cooling fins between the channels. When the liquid has cooled, it leaves the radiator through the bottom radiator hose (surprise!). This hose usually has a spring inside it to prevent it from collapsing when the water pump draws coolant from the radiator. (If it collapses anyway, Chapter 12 has instructions for replacing it.)

Smaller-diameter hoses also lead from your engine to the heater core (see the later section, “The Heater Core”). Some vehicles have a small bypass hose near the thermostat as well (see the later section, “The Thermostat”). These hoses are an important part of the cooling system because they’re designed to carry the liquid in it from one component to another.

The coolant recovery system

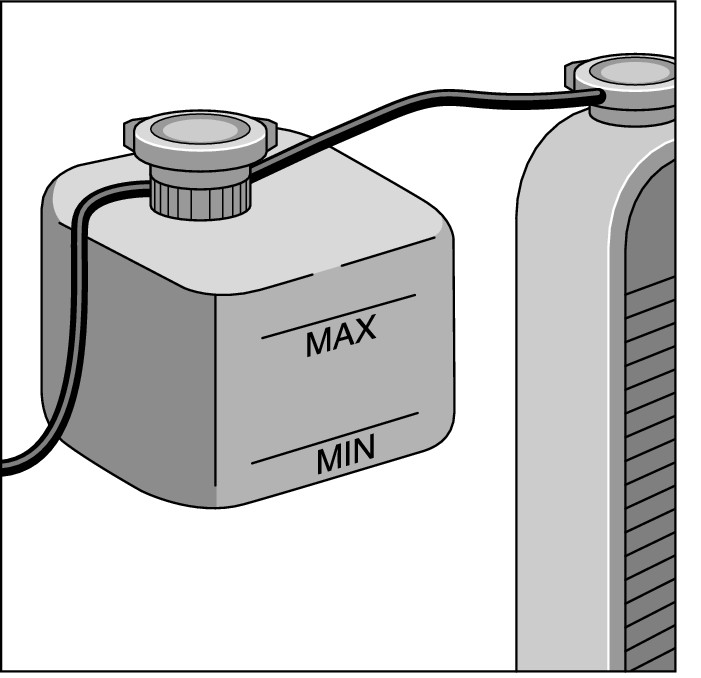

A coolant recovery system is a plastic or metal container with two little hoses coming out of the cap (see Figure 11-2). One hose leads to the radiator, and the other serves as an overflow pipe for the container, which holds an extra supply of water and coolant in case the system loses any.

|

Figure 11-2: A coolant recovery system. |

|

Some of today’s new vehicles have pressurized reservoirs. In these cases, you may find the pressure cap (which I get into in the next section) on the reservoir and not on the radiator. I’ve been told by radiator specialists that, on some vehicles, this system doesn’t work very efficiently because, as the pressure builds up in the coolant reservoir, it forces the coolant out of the overflow pipe and onto the street. Not only is this overflow a toxic hazard, but as the coolant supply diminishes, the chance of the engine overheating increases, leading to a vicious circle.

Many recovery systems are considered “sealed” because you add water and coolant by opening the cap on the reservoir rather than on the radiator. You also check the level of liquid in the system by seeing whether it reaches the “Max” level shown on the side of the container rather than by opening the radiator and looking inside. (For instructions on adding liquid to a sealed system safely, see Chapter 12.)

The pressure cap

To further retard the boiling point of the liquid in the cooling system, the entire system is placed under pressure. This pressure generally runs between 7 and 16 pounds per square inch (psi). As the pressure increases, the boiling point rises as well. This combination of pressure plus coolant gives the liquid in your cooling system the capability to resist boiling at temperatures that can rise as high as 250°F or more in some vehicles.

To keep the lid on the pressure in the system and to provide a convenient place to add water and coolant, each radiator has a removable radiator pressure cap located on either its radiator fill hole or its coolant recovery system.

.jpg)

If your vehicle overheats on the highway, Chapter 21 can get you cooled down safely. Chapter 12 offers remedies for other overheating problems.

The Fan

Air rushing through the radiator cools things off when you’re driving merrily down the highway, but a fresh supply of air doesn’t move through the radiator fins when the vehicle is standing still or crawling its way through heavy traffic. For this purpose, the fan is positioned so that it cools the liquid in the radiator (refer to Figure 11-1). Today, most fans have a plastic shroud that funnels air through the radiator. Some vehicles have air dams that help force the air up through the radiator from below.

Some vehicles now have two fans because styling changes that have lowered the profile of the hood area have caused radiators to get lower and longer, meaning that a single fan doesn’t cover the entire surface. These two fans are sometimes run by electric thermostats that aren’t connected to the water pump at all (I cover the water pump in the next section).

The Water Pump

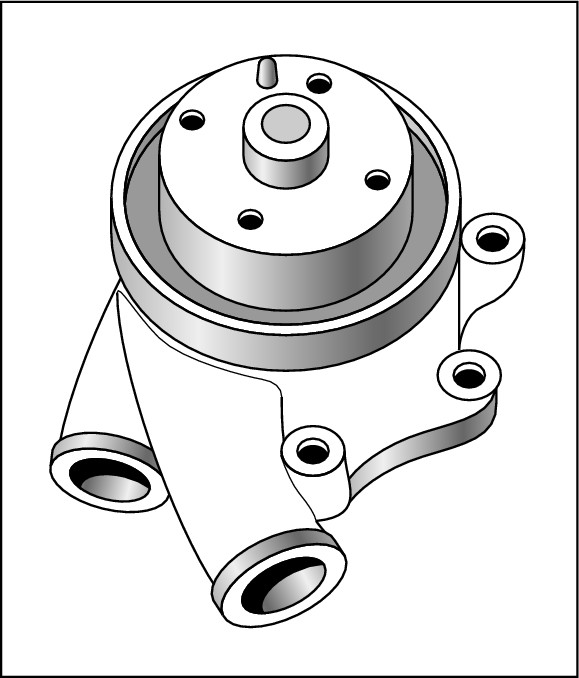

The water pump (see Figures 11-1 and 11-3) draws the cooled liquid from the radiator through the bottom radiator hose and sends it to the engine, where it circulates through water jackets located around the combustion chambers in the cylinders and other hot spots. Then the liquid returns to the radiator to cool off again. An accessory belt connected to the crankshaft drives some water pumps, while some overhead cam engines drive the water pump with the timing belt. Chapter 2 tells you how to check accessory belts, and Chapter 12 has instructions for adjusting and replacing them.

|

Figure 11-3: A water pump. |

|

The Thermostat

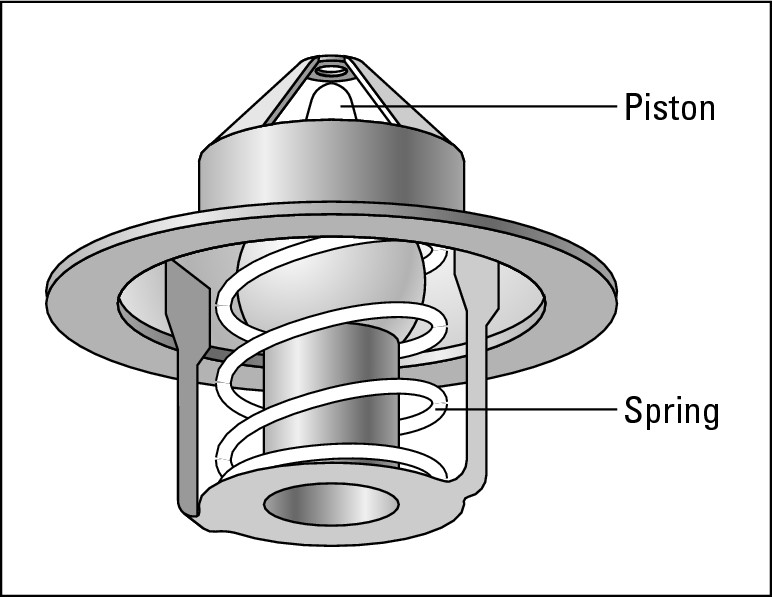

The thermostat is the only part of the cooling system that does not cool things off. Instead, it helps the liquid in the cooling system warm up the engine quickly.

|

Figure 11-4: A thermostat. |

|

The Heater Core

The heater core is located inside the vehicle between the instrument panel and the firewall (refer to Figure 11-1). It looks like a miniature radiator minus the fill neck and cap. The purpose of the heater core is to provide heat for the passenger compartment. The same liquid that the water pump circulates throughout the engine also circulates through the heater core when the engine is operating. When you get chilly, you can direct air across the heater core and heat the interior of your vehicle by turning on the inside fan. Because the heater core is relatively passive, it usually doesn’t need attention unless it breaks.

The Transmission Cooler

Vehicles with automatic transmissions have a transmission cooler located in or near the bottom or side of the radiator (refer to Figure 11-1). The transmission fluid circulates from the hot transmission to the cooler, which cools it and returns it to the transmission. If the transmission cooler on your vehicle is working properly, you don’t need to monkey with it. If it leaks, have it repaired by a professional.

Air Conditioning

Air conditioning is now standard equipment on most vehicles rather than an option. It uses refrigerant to remove the heat from the air (rather than cooling it) and a blower to send the cool air into the passenger compartment.

.jpg)