Chapter 17

How to Keep Your Car from Getting Sore Feet: Tires, Alignment, and Balancing

In This Chapter

Understanding the anatomy of a tire

Understanding the anatomy of a tire

Deciphering the data on the sidewalls

Deciphering the data on the sidewalls

Choosing the right tires for your vehicle

Choosing the right tires for your vehicle

Maintaining your tires: Checking air pressure, rotating, aligning, and balancing

Maintaining your tires: Checking air pressure, rotating, aligning, and balancing

Examining your tires for wear and getting compensated for defective tires

Examining your tires for wear and getting compensated for defective tires

If you think about tires only when it’s time to buy new ones, you need to think again. The right tires in the right condition can enhance your driving experience and make it safer. In fact, your brakes and your tires have a two-way relationship: Poor braking action results in increased tire wear, but properly balanced and aligned wheels and properly inflated tires in good condition can help stop your car up to 25 percent faster!

.jpg)

In this chapter, I tell you about the kinds of tires available. (You can buy different types and grades, and just as you wouldn’t wear your finest shoes to the beach, you don’t want to put the most expensive, long-lasting, high-speed set of tires on an old car that just goes back and forth to the shopping center.) I also tell you how to check your tires and how to read your treads for clues about how well your vehicle is performing — and how well you’re driving. If these clues show that you need to have your tires and wheels balanced or aligned or your tires replaced, I provide enough information for you to be sure that the work is done the right way for the right price.

You don’t have to do much (in terms of physical labor) with this chapter, so just find a comfortable place to read, relax, and enjoy. For information about how to change a flat tire, see Chapter 1.

Tire Construction

Every tire has several major parts (see Figure 17-1). You find out more about them in the next section, “The Secrets on Your Sidewalls, Revealed!,” which decodes all the useful data molded into the sidewall of a tire. But to start, here’s a brief description of each part:

The sidewall is the part of the tire between the tread and the bead. It keeps the air in, protects the components inside the tire, and keeps it stable.

The sidewall is the part of the tire between the tread and the bead. It keeps the air in, protects the components inside the tire, and keeps it stable.

The tread is the part of the tire that gets most of the wear and tear. It used to just be made of rubber (hence the phrases, “where the rubber meets the road” and “burning rubber”). Today, the tread can be made from natural rubber, synthetics, or both. The tread patterns help the tire grip the road and resist puncturing. These patterns also are excellent indicators of tire wear and have built-in treadwear indicators that let you know when it’s time to replace your tires. I get into reading these clues later in this chapter, in the section called — unsurprisingly — “Checking your tires for wear.”

The tread is the part of the tire that gets most of the wear and tear. It used to just be made of rubber (hence the phrases, “where the rubber meets the road” and “burning rubber”). Today, the tread can be made from natural rubber, synthetics, or both. The tread patterns help the tire grip the road and resist puncturing. These patterns also are excellent indicators of tire wear and have built-in treadwear indicators that let you know when it’s time to replace your tires. I get into reading these clues later in this chapter, in the section called — unsurprisingly — “Checking your tires for wear.”

The bead is a hoop of rubber-coated steel wire that’s shaped to help hold the tire onto the rim of the wheel. Most tires have several beads grouped into a bead bundle.

The bead is a hoop of rubber-coated steel wire that’s shaped to help hold the tire onto the rim of the wheel. Most tires have several beads grouped into a bead bundle.

The body of the tire is located beneath the tread and the sidewalls. It helps the tire keep its shape when inflated instead of blowing up like a balloon.

The body of the tire is located beneath the tread and the sidewalls. It helps the tire keep its shape when inflated instead of blowing up like a balloon.

The plies make up the body of the tire. They’re rubber-coated layers of various materials (the most popular is polyester cord). The more plies, the stronger the tire. The innermost belt is called a liner; it provides a stable base for layering all the plies. High-speed tires sometimes have cap plies on top of the regular ones to keep the plies and belts in place.

The plies make up the body of the tire. They’re rubber-coated layers of various materials (the most popular is polyester cord). The more plies, the stronger the tire. The innermost belt is called a liner; it provides a stable base for layering all the plies. High-speed tires sometimes have cap plies on top of the regular ones to keep the plies and belts in place.

The belts are located between the body and the tread. They provide longer wear, puncture resistance, and more directional stability and are usually made of rubber-coated steel. Belts also can be made of aramid (which is harder than steel), fiberglass, polyester, rayon, or nylon. But steel is the most popular type of belt material.

The belts are located between the body and the tread. They provide longer wear, puncture resistance, and more directional stability and are usually made of rubber-coated steel. Belts also can be made of aramid (which is harder than steel), fiberglass, polyester, rayon, or nylon. But steel is the most popular type of belt material.

The tire valve lets air into and out of the tire. The valve core prevents air from escaping. Each valve should have a valve cap to keep dirt and moisture from getting into the tire.

The tire valve lets air into and out of the tire. The valve core prevents air from escaping. Each valve should have a valve cap to keep dirt and moisture from getting into the tire.

|

Figure 17-1: Anatomy of a tire. |

|

Radial tires have become the standard because they provide better handling, especially at high speeds; they tend to grip the road more efficiently, especially when cornering; and they can deliver twice the mileage of bias-ply and belted tires. Radial tires run cooler because they have less internal friction. Wear varies; some high-performance cars with tire treads made of a relatively soft compound that provides better road grip get only a few thousands miles per set if driven hard. But for most vehicles, tires last from 25,000 miles and up, depending on the belt material used. Top-of-the-line steel-belted radials can last from 40,000 to as many as 100,000 miles under average driving conditions. To decide what type of tire is right for your vehicle, see “Tips for Buying Tires,” later in this chapter.

The Secrets on Your Sidewalls, Revealed!

Many people are willing to spend extra dollars for tires with names like MACHO WILDCATS or TOUGH GUYS embossed in large white letters on the sidewalls, but did you know that the wealth of information that is embossed on those sidewalls in quiet little black letters can be more valuable in the long run? And this information is free — if you know how to decode it. Even if you’re not the inquisitive type, the data in the following sections can help you when you buy and maintain tires. Figure 17-2 shows you all the different types of codes you can find on the sidewall of a tire.

|

Figure 17-2: The secrets of your sidewalls, revealed! |

|

Adapted from the NHTSA (www.safercar.gov)

Tire codes

P = Type of vehicle. In this case, P means passenger. Other codes include LT for light truck and T for temporary or spare tire. Small pickup trucks and RVs often come with P-rated tires because they aren’t expected to carry heavy loads.

P = Type of vehicle. In this case, P means passenger. Other codes include LT for light truck and T for temporary or spare tire. Small pickup trucks and RVs often come with P-rated tires because they aren’t expected to carry heavy loads.

If you’re planning to do any heavy hauling, look for a vehicle equipped with LTs. (Also check the load index information farther down this list.)

215 = Tire section width. This is measured across the tread, from one sidewall to the other, in millimeters. In this case, the tire width is 215 mm. Remember, the wider the tire, the higher the number.

215 = Tire section width. This is measured across the tread, from one sidewall to the other, in millimeters. In this case, the tire width is 215 mm. Remember, the wider the tire, the higher the number.

65 = Aspect ratio or tire series. This is the ratio of the tire’s sidewall height to its width. In this case, the tire’s sidewall height is 65 percent of its width. Tires with a low aspect ratio (less than 70) are referred to as low-profile tires and usually are found on the touring tires or high performance tires described in the later section “Passenger vehicles.”

65 = Aspect ratio or tire series. This is the ratio of the tire’s sidewall height to its width. In this case, the tire’s sidewall height is 65 percent of its width. Tires with a low aspect ratio (less than 70) are referred to as low-profile tires and usually are found on the touring tires or high performance tires described in the later section “Passenger vehicles.”

R = Tire type. For tire type, R means radial and LT means light truck. Most tires on passenger vehicles are radials.

R = Tire type. For tire type, R means radial and LT means light truck. Most tires on passenger vehicles are radials.

15 = Diameter of the wheel. The diameter is measured in inches. In this case, the diameter is 15 inches. Buying new wheels with larger diameters (and 18- to 20-inch wheels aren’t uncommon these days) requires buying new tires with diameters to match.

15 = Diameter of the wheel. The diameter is measured in inches. In this case, the diameter is 15 inches. Buying new wheels with larger diameters (and 18- to 20-inch wheels aren’t uncommon these days) requires buying new tires with diameters to match.

89 = Load index. This number refers to how much weight the tire can carry. This information is especially important if you carry heavy loads (including several obese passengers), haul a lot of gear on camping trips, or if you’re moving your kid to a college dormitory! There’s no law that requires the manufacturer to put load index information on the sidewall, but your

owner’s manual

may have it. If not, consult a tire dealer.

89 = Load index. This number refers to how much weight the tire can carry. This information is especially important if you carry heavy loads (including several obese passengers), haul a lot of gear on camping trips, or if you’re moving your kid to a college dormitory! There’s no law that requires the manufacturer to put load index information on the sidewall, but your

owner’s manual

may have it. If not, consult a tire dealer.

H = Speed rating. The speed rating of the tire is described in the next section. Providing this information on the sidewall isn’t required by law.

H = Speed rating. The speed rating of the tire is described in the next section. Providing this information on the sidewall isn’t required by law.

M+S or M/S = Mud and snow codes. If you live in or drive through areas with extreme conditions, look for these codes on the sidewall.

M+S or M/S = Mud and snow codes. If you live in or drive through areas with extreme conditions, look for these codes on the sidewall.

Speed ratings

Sometimes an additional letter appears between the load index and tire type, such as P21 5/65R15 89H in Figure 17-2. The letter H refers to the speed rating, which represents the safest maximum speed for the tire. It tells you nothing about a tire’s construction, handling, or wearability but rather measures the tire’s ability to dissipate heat so that it can endure the high temperatures that high speeds create.

Here’s a list of what the most common speed rating letters mean:

Q = 99 mph

Q = 99 mph

R = 106 mph

R = 106 mph

S = 112 mph

S = 112 mph

T = 118 mph

T = 118 mph

U = 124 mph

U = 124 mph

H = 130 mph

H = 130 mph

V = 149 mph

V = 149 mph

W = 168 mph

W = 168 mph

Y = 186 mph

Y = 186 mph

ZR = Sometimes used for tires that can go over 149 mph; always used for tires that can go over 186 mph

ZR = Sometimes used for tires that can go over 149 mph; always used for tires that can go over 186 mph

Tires with the most common speed ratings, T and H, can go well over the speed limit. They’re usually good buys because tires with higher speed ratings are more durable. However, if you usually drive at low speeds on local streets and rarely drive on the highway, the extra expense may not be worth it.

DOT identification and registration

The Department of Transportation (DOT) identification number on the sidewall (refer to Figure 17-2) has a wealth of information. Here’s what the letters and numbers of the DOT code mean:

DOT indicates that the tire meets or exceeds United States Department of Transportation safety standards.

DOT indicates that the tire meets or exceeds United States Department of Transportation safety standards.

The next two numbers or letters identify the plant where the tire was made.

The next two numbers or letters identify the plant where the tire was made.

The next numbers or letters are marketing codes provided by the manufacturer. They serve as a registration number that identifies the tire in case of a recall. (You can find more information on recalls in the later section “Dealing with Defective Tires.”)

The next numbers or letters are marketing codes provided by the manufacturer. They serve as a registration number that identifies the tire in case of a recall. (You can find more information on recalls in the later section “Dealing with Defective Tires.”)

The last four numbers are the week and year the tire was produced. For example, 2408 would mean the tire was made during the twenty-fourth week of 2008.

The last four numbers are the week and year the tire was produced. For example, 2408 would mean the tire was made during the twenty-fourth week of 2008.

.jpg)

Under federal law, the dealer is required to put the tire’s DOT number and the dealer’s name and address on a form that’s sent to the manufacturer. Although tire outlets owned by manufacturers and certain brand-name outlets must send them in to the manufacturer, independent tire dealers can simply fill out the forms and give them to customers to mail to the manufacturer. For more ideas about buying tires, see “Tips for Buying Tires” later in this chapter.

.jpg)

Tire quality grade codes

The Uniform Tire Quality Grading System (UTQGS) rates tires for treadwear, traction, and temperature, but although the federal government requires that ratings be determined on most passenger car tires, they’re set by tire manufacturers and not by an objective testing service. Personal driving habits, type of vehicle, road conditions and surfaces, and tire maintenance all have a huge impact on a tire’s longevity and performance.

Look for the tire quality grades shown in Figure 17-2 on the sidewalls of the tires on your vehicle or on stickers affixed to the treads of tires at a dealership. Here’s what they mean:

Treadwear: This comparative number grade is based on carefully controlled testing conditions. In the real world, a tire rated 200 would have twice the treadwear of one rated 100 — if all other wear factors were equal.

Treadwear: This comparative number grade is based on carefully controlled testing conditions. In the real world, a tire rated 200 would have twice the treadwear of one rated 100 — if all other wear factors were equal.

Traction: This AA, A, B, or C grade represents the tire’s ability to stop on wet pavement under controlled conditions (with AA being the best possible rating). The grades are based on straight-ahead braking only, not on cornering or turning. The higher the grade, the shorter distance it takes to stop the vehicle. A tire with a C grade just meets the government’s test, whereas tires with B, A, and AA (in ascending order) exceed government standards.

Traction: This AA, A, B, or C grade represents the tire’s ability to stop on wet pavement under controlled conditions (with AA being the best possible rating). The grades are based on straight-ahead braking only, not on cornering or turning. The higher the grade, the shorter distance it takes to stop the vehicle. A tire with a C grade just meets the government’s test, whereas tires with B, A, and AA (in ascending order) exceed government standards.

Temperature: This A, B, or C grade represents heat resistance and the tire’s capability to dissipate the heat if the tire is inflated properly and not overloaded. Grade C meets U.S. minimum standards, while grades B and A exceed government standards.

Temperature: This A, B, or C grade represents heat resistance and the tire’s capability to dissipate the heat if the tire is inflated properly and not overloaded. Grade C meets U.S. minimum standards, while grades B and A exceed government standards.

Other sidewall information

Check the sidewalls shown in Figure 17-2 and on your own vehicle for the following safety data:

MAX LOAD: How much weight the tire can bear safely, usually expressed in both kilograms (kg) and pounds (lbs)

MAX LOAD: How much weight the tire can bear safely, usually expressed in both kilograms (kg) and pounds (lbs)

MAX PRESS: The maximum air pressure the tire can safely hold, usually expressed in pounds per square inch

(psi)

MAX PRESS: The maximum air pressure the tire can safely hold, usually expressed in pounds per square inch

(psi)

.jpg)

MAX PRESS is not the proper pressure to maintain in your tires! To find the amount of psi the tires should normally hold, look for the manufacturer’s recommended pressure for the best handling and wear on the tire decal on the door, door pillar, console, glove box, or trunk of your vehicle.

You can find instructions for checking tire pressure, reading treads for clues, and other work that you can do on your tires in the “Caring for Your Tires” section later in this chapter.

Types of Tires

As I explain earlier in this chapter, if you use the proper type of tires on your vehicle, they will wear better, provide better traction, provide the best braking action, and are safer than the wrong tires. Here are some of the types of tires that you may want to consider.

Passenger vehicles

The following types of tires are suitable for passenger vehicles, which include everything except trucks and SUVs (covered in the following section), race cars, construction equipment, and other specialized vehicles:

Basic all-season tires are standard equipment on most popular vehicles because they usually provide a comfortable ride and good treadwear. The speed rating (see the “Speed ratings” section earlier in the chapter) is usually T or H. If “M+S” is printed on the

sidewall,

the tire meets standards for mud and snow, but if you live in an area with really inclement weather, you’ll probably need snow tires instead.

Basic all-season tires are standard equipment on most popular vehicles because they usually provide a comfortable ride and good treadwear. The speed rating (see the “Speed ratings” section earlier in the chapter) is usually T or H. If “M+S” is printed on the

sidewall,

the tire meets standards for mud and snow, but if you live in an area with really inclement weather, you’ll probably need snow tires instead.

Touring tires are generally more expensive than basic all-season tires and can be found on sportier vehicle models because the tires are supposed to handle better and grip the road at higher speeds in dry conditions. Whether they’re worth the money depends on the individual product. Touring tires have higher speed ratings, lower profiles (sometimes called lower aspect ratios), and may not be as durable as all-season tires.

Touring tires are generally more expensive than basic all-season tires and can be found on sportier vehicle models because the tires are supposed to handle better and grip the road at higher speeds in dry conditions. Whether they’re worth the money depends on the individual product. Touring tires have higher speed ratings, lower profiles (sometimes called lower aspect ratios), and may not be as durable as all-season tires.

Performance tires are designed for people who drive aggressively. They perform better in terms of braking and cornering in dry conditions but usually are noisier and wear out more quickly than all-season tires. They’re usually speed-rated at least at H and have a wide, squatty, low profile.

Performance tires are designed for people who drive aggressively. They perform better in terms of braking and cornering in dry conditions but usually are noisier and wear out more quickly than all-season tires. They’re usually speed-rated at least at H and have a wide, squatty, low profile.

Ultra-high-performance tires have both the positive and the negative aspects of performance tires to a greater degree: They go faster and brake and handle better in both wet and dry conditions, but they ride less comfortably and wear out even faster. They may have profiles as low as 25 and usually are speed-rated V through ZR.

Ultra-high-performance tires have both the positive and the negative aspects of performance tires to a greater degree: They go faster and brake and handle better in both wet and dry conditions, but they ride less comfortably and wear out even faster. They may have profiles as low as 25 and usually are speed-rated V through ZR.

.jpg)

Tires for trucks and SUVs

SUVs, small pickup trucks, and vans may come with passenger-rated tires or truck tires. What you need depends on where you usually drive and how much you carry. Here are the categories for truck tires:

Light-truck tires are intended for use on light trucks and SUVs. They come in a variety of styles designed for normal conditions, driving on- or off-road, or both. The thicker treads on the off-road variety offer better traction on unpaved surfaces. Light-truck tires also vary for carrying normal, heavy, and extra-heavy loads.

Light-truck tires are intended for use on light trucks and SUVs. They come in a variety of styles designed for normal conditions, driving on- or off-road, or both. The thicker treads on the off-road variety offer better traction on unpaved surfaces. Light-truck tires also vary for carrying normal, heavy, and extra-heavy loads.

Street/sport truck tires are pretty much the same as all-season tires except that they have a sportier look and are supposed to handle better.

Street/sport truck tires are pretty much the same as all-season tires except that they have a sportier look and are supposed to handle better.

Highway tires are useful if you drive a larger van or pickup truck because they can carry heavier loads.

Highway tires are useful if you drive a larger van or pickup truck because they can carry heavier loads.

Off-road tires have treads designed to deal with really difficult terrain. Because they’re noisier and not as comfortable or fuel-efficient on paved roads as street/sport or highway tires, forget these tires unless you really plan to head for the hills or desperately want to project a more macho image enough to pay bigger bucks for tires and fuel. However, a compromise may be all-terrain off-road tires, which may not get you quite as far off the beaten path but are more comfortable and quieter than these heavy-duty beauties.

Off-road tires have treads designed to deal with really difficult terrain. Because they’re noisier and not as comfortable or fuel-efficient on paved roads as street/sport or highway tires, forget these tires unless you really plan to head for the hills or desperately want to project a more macho image enough to pay bigger bucks for tires and fuel. However, a compromise may be all-terrain off-road tires, which may not get you quite as far off the beaten path but are more comfortable and quieter than these heavy-duty beauties.

Snow tires may be better than all-season tires for driving in areas with heavy snowfall or muddy roads. Their treads usually have wider grooves and protuberances called lugs to provide better traction, but they’re noisy, don’t handle as well on dry roads, and are generally less fuel- efficient than all-season tires, so use them only when necessary.

Snow tires may be better than all-season tires for driving in areas with heavy snowfall or muddy roads. Their treads usually have wider grooves and protuberances called lugs to provide better traction, but they’re noisy, don’t handle as well on dry roads, and are generally less fuel- efficient than all-season tires, so use them only when necessary.

Specialized Tire Systems

Some tires are so sophisticated that they require a special system to enable them to communicate with the driver and/or other automotive systems. The following tires and systems fall into this category.

Run-flat tires

Run-flat tires can be driven on without any air pressure inside the tire! This means that you don’t face the stress and danger involved in having a blow-out or changing a tire at the side of the road. Run-flats can be constructed in two different ways:

Self-supporting run-flat tires have stronger sidewalls to keep the tire from collapsing if the air pressure inside the tire drops. Layers of rubber and heat-resistant cord, and sometimes support wedges, are used in the sidewall.

Self-supporting run-flat tires have stronger sidewalls to keep the tire from collapsing if the air pressure inside the tire drops. Layers of rubber and heat-resistant cord, and sometimes support wedges, are used in the sidewall.

The PAX system designed by Michelin allows you to drive up to 55 mph for up to 125 miles with zero air pressure inside a tire! The system includes a tire, a tire-monitoring system that measures the temperature and the pressure of the air in the tire, and a wheel with a strong inner ring that supports the tread if the tire loses half its air pressure. Unlike most other tires, the system also features a special anchoring mechanism that keeps the tire on the wheel if the air pressure in the tire drops.

The PAX system designed by Michelin allows you to drive up to 55 mph for up to 125 miles with zero air pressure inside a tire! The system includes a tire, a tire-monitoring system that measures the temperature and the pressure of the air in the tire, and a wheel with a strong inner ring that supports the tread if the tire loses half its air pressure. Unlike most other tires, the system also features a special anchoring mechanism that keeps the tire on the wheel if the air pressure in the tire drops.

Michelin claims that PAX system tires wear longer and get better fuel economy than traditional tires because of reduced rolling resistance. If the tread area is punctured, the tire can be repaired and the support ring reused. You can read more about this system at www.michelinman.com/difference/innovation/paxsystem.html.

Under normal circumstances, properly inflated run-flat tires should last the same 30,000 to 40,000 miles as many ordinary tires. You can drive run-flat tires with no air pressure in them for 50 to 125 miles at speeds up to 50 or 55 mph without further damaging the tire. Although run-flats are durable, running on them without air at high speeds for a long period can damage them. Because the driver often can’t feel any difference when a run-flat goes flat, automakers incorporate low-pressure warning systems to alert the driver that a tire has lost pressure and to drive more slowly and get the tire repaired as soon as possible to avoid further damage to the tire or wheel. See the next section for more details on these warning systems.

.jpg)

Also be aware that vehicles that come equipped with run-flats have suspension systems that are tuned to the rigidity of the sidewalls. So if you replace the tires on a vehicle with a standard suspension with run-flats, there may be a difference in the way your vehicle handles, and the ride may be a bit harder and noisier.

Be sure to purchase run-flats and have them installed at a car or tire dealer that knows how to do it properly. There’s a good case to be made that the expense is well worthwhile compared to the possible consequences of blow-outs and flat tires.

Low-pressure warning systems

You can find two types of low-pressure systems on modern vehicles:

Direct systems: The only option for vehicles that didn’t come equipped with run-flats. They employ a

sensor

on the wheel that usually is placed opposite the valve stem. The sensor sends a signal to a unit that usually activates a warning light on the instrument panel (some systems have warning chimes). The sensors are powered by small, five-year batteries that usually are replaced with each new set of tires.

Direct systems: The only option for vehicles that didn’t come equipped with run-flats. They employ a

sensor

on the wheel that usually is placed opposite the valve stem. The sensor sends a signal to a unit that usually activates a warning light on the instrument panel (some systems have warning chimes). The sensors are powered by small, five-year batteries that usually are replaced with each new set of tires.

Indirect systems: The least expensive option and therefore the type that automakers often prefer to use. They employ the same sensors as are used on

ABS

systems to measure the speed of the wheels. However, when used with run-flats, an indirect system needs to be specially tuned to be sensitive enough to the very slight differences between an inflated run-flat and one that’s flat.

Indirect systems: The least expensive option and therefore the type that automakers often prefer to use. They employ the same sensors as are used on

ABS

systems to measure the speed of the wheels. However, when used with run-flats, an indirect system needs to be specially tuned to be sensitive enough to the very slight differences between an inflated run-flat and one that’s flat.

Self-inflating tire systems

Tips for Buying Tires

Tire wear is affected by a number of factors: the condition of the vehicle’s brake system and suspension system, inflation and alignment, driving and braking techniques, driving at high speeds (which raises tire temperatures and causes them to wear prematurely), how great a load you carry, road conditions, and climate. So, before you rush out and buy a set of tires, you have several things to consider:

Are you hard on tires? If you tend to “burn rubber” when cornering, starting, and stopping, you know where that rubber comes from. A pair of cheaply made tires will wear out quickly, so buy the best quality you can afford. And learn not to be such a lead-foot!

Do you drive a great deal and do most of your driving on high-speed highways? A tire with a harder tread compound will take longer to wear out under these conditions. See the “Tire quality grade codes” section earlier in this chapter for more information about treadwear ratings.

Do you drive a lot on unpaved rocky roads, carry heavy loads, or leave your vehicle in the hot sun for long hours? If so, you need higher-quality tires that have the stamina to endure these challenges. Look for extra load -rated or even LT (light truck) tires. A tire dealer can tell you which tires are rated for extra loads.

What’s the weather like in your area? Today, front-wheel drive vehicles with high-tech all-season tires get better traction than the old snow tires, which you had to replace when warm weather set in. However, if you drive under extreme conditions, you may want to check out tires designed for them.

Do you drive mostly in local stop-and-go traffic, with many turns? Softer tires with wider treads will suit you best.

.jpg)

Do you feel vulnerable on the road? If you worry about having a blow-out, don’t feel that you can change a flat yourself, or are afraid that you’ll be car-jacked or injured if you stop to change a tire, run-flat tires (described earlier in the chapter) are well worth owning.

In addition to knowing which kind of tire is best for your vehicle and understanding the tire codes (explained in the section called “The Secrets on Your Sidewalls, Revealed!”), keep the following tips in mind when you shop for tires:

You can find the proper tire size for your car in your

owner’s manual

or on a sticker affixed to the vehicle. If neither exists, ask your dealer.

You can find the proper tire size for your car in your

owner’s manual

or on a sticker affixed to the vehicle. If neither exists, ask your dealer.

Although you should never buy tires that are smaller than those specified for your vehicle, you often can buy tires a size or two larger (if the car’s wheel clearance allows it) for better handling or load-carrying ability. However, buy these larger tires in pairs and place them on the same axle.

Ask your mechanic or a reputable tire or auto dealer for advice about the proper size range for your vehicle. Sometimes buying larger tires also requires larger wheels, which can quickly get expensive.

Although you should never buy tires that are smaller than those specified for your vehicle, you often can buy tires a size or two larger (if the car’s wheel clearance allows it) for better handling or load-carrying ability. However, buy these larger tires in pairs and place them on the same axle.

Ask your mechanic or a reputable tire or auto dealer for advice about the proper size range for your vehicle. Sometimes buying larger tires also requires larger wheels, which can quickly get expensive.

.jpg)

Never use two different-sized tires on the same axle.

Never use two different-sized tires on the same axle.

If you’re replacing just one or two tires, put the new ones on the front for better cornering control and braking (because weight transfers to the front tires when you brake). Of course, if you have a sports car or performance vehicle with rear tires that are larger than the front tires, you have to make sure you keep the proper sizes on each axle.

If you’re replacing just one or two tires, put the new ones on the front for better cornering control and braking (because weight transfers to the front tires when you brake). Of course, if you have a sports car or performance vehicle with rear tires that are larger than the front tires, you have to make sure you keep the proper sizes on each axle.

You have to “break in” new tires, so don’t drive faster than 60 mph for the first 50 miles on a new tire or spare.

You have to “break in” new tires, so don’t drive faster than 60 mph for the first 50 miles on a new tire or spare.

Store tires that you aren’t using in the dark, away from extreme heat and electric motors that create ozone.

Store tires that you aren’t using in the dark, away from extreme heat and electric motors that create ozone.

Retreads: Bargains or blowouts?

Millions of tires are discarded every year, and an entire industry has developed to put them back in service by replacing the worn tread areas with new ones. The retreading process involves grinding the tread off an otherwise sound old tire and winding a strand of uncured rubber around the tire. Then the tire is placed in a mold, where the rubber is cured under heat and pressure and the tread itself is shaped. Finally, the tire is painted.

For many years, retreads had a reputation of being unreliable, and most consumers assumed that the strips of tread they saw littering the highways came from retreaded tires that had disintegrated on the road. But today, advances in retreading have raised their quality. Although they are now hardly used on passenger vehicles, and high-performance vehicles are probably better off with new tires, most large commercial trucks (such as semis) use them, as do virtually all the world’s airlines. Retreaded tires are also used on school buses, racing cars, taxis, trucks, and federal and U.S. military vehicles.

You can find out more about retreads at www.retread.org.

Caring for Your Tires

Tires don’t require a great deal of maintenance, but the jobs in this section will pay off handsomely by increasing your tires’ longevity, handling, and performance as well as providing you with a more comfortable ride.

Checking tire inflation pressure

The single most important factor in caring for your tires is maintaining the correct inflation pressure. True, most newer vehicles have the built-in pressure-monitoring systems described earlier in this chapter, but there are still many vehicles on the road without them.

.jpg)

Here’s how you check the air pressure in your tires:

1. Buy an accurate tire gauge at a hardware store or auto supply store.

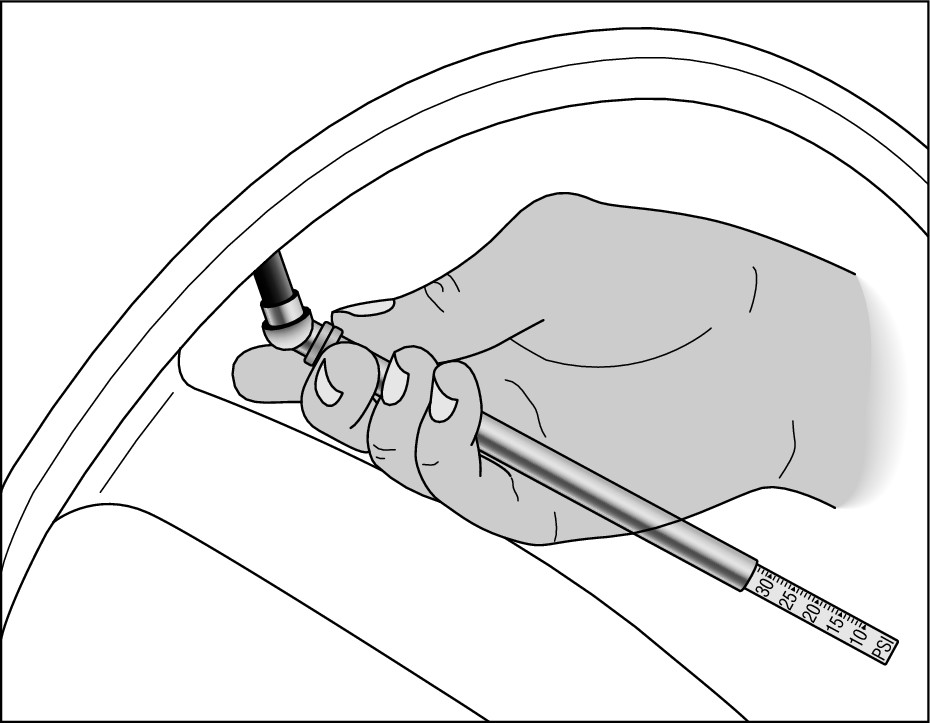

Figure 17-3 shows you what one type of tire gauge looks like.

|

Figure 17-3: The number on the tire gauge indicates air pressure in psi. |

|

2. Determine the proper air pressure for your tires by looking for the proper inflation pressure on the tire decal.

You can find the tire decal on one of the doors, door pillars, glove box, console, or trunk. Sometimes the tire decal specifies one pressure for the front tires and a different pressure for the rear tires.

.jpg)

Don’t consult the tire’s sidewall for the proper inflation pressure. The sidewall lists the maximum pressure that the tire is capable of handling, not the pressure that’s best for performance and wear (unless you’re carrying heavy loads).

3. Remove the little cap from the tire valve that sticks out of your tire near the wheel rim.

You don’t have to remove your wheel cover or hubcap for this step.

4. Place the open, rounded end of the tire gauge against the valve so that the little pin in the gauge contacts the pin in the valve.

5. Press the gauge against the valve stem.

You’ll hear a hissing sound as air starts to escape from the tire. At this point, a little stick will emerge from the other end of the tire gauge valve (see Figure 17-3). It emerges partway almost as soon as the air starts to hiss and stops emerging almost immediately.

6. Without pushing the stick back in, remove the gauge from the tire valve.

7. Look at the stick without touching it. There are little numbers on it; pay attention to the last number showing.

The last number is the amount of air pressure (in psi) in your tire, as shown in Figure 17-3. Does the gauge indicate the proper amount of pressure recommended on the decal?

If the pressure seems too low, push the stick back in and press the gauge against the valve stem again. If the reading doesn’t change, you need more air.

Instead of a stick, some tire gauges feature a dial on the face of the gauge that shows the air pressure, and digital tire pressure gauges are becoming increasingly common. If you have one of these, just check to see if the needle on the dial — or the digital readout — shows the correct psi. If it doesn’t, you need to add air to the tire until the reading is correct. But you knew that, right?

8. Repeat Steps 3 through 7 for each tire.

Run-flat tires and little temporary spare tires can lose pressure over time, so be sure to check them, too.

9. Add air, if necessary, by following the steps in the next section, “Adding air to your tires.”

Adding air to your tires

If your tires appear to be low, check the pressure according to the steps in the preceding section and note the amount that they’re underinflated. Then drive to a local gas station.

Follow these steps to add air to your tires:

1. Park your vehicle so that you can reach all four tires with the air hose.

2. Remove the cap from the tire valve on the first tire.

.jpg)

3. Use your tire gauge to check the air pressure in the tire and see how much it has changed since your last reading (tests have shown that tire gauges on the air hoses at many gas stations are inaccurate).

The pressure will have increased because driving causes the tires to heat up and the air inside them to expand. To avoid overinflating the tire, no matter what the second reading indicates, you should only add the same amount of air that the tire lacked before you drove it to the station.

4. Use the air hose to add air in short bursts, checking the pressure after each time with your tire gauge.

5. If you add too much air, let some out by pressing the pin on the tire valve with the back of the air hose nozzle or with the little knob on the back of the rounded end of the tire gauge.

6. Keep checking the pressure until you get it right.

Don’t get discouraged if you have to keep adjusting the air pressure. No one hits it on the head the first time!

Rotating your tires

.jpg)

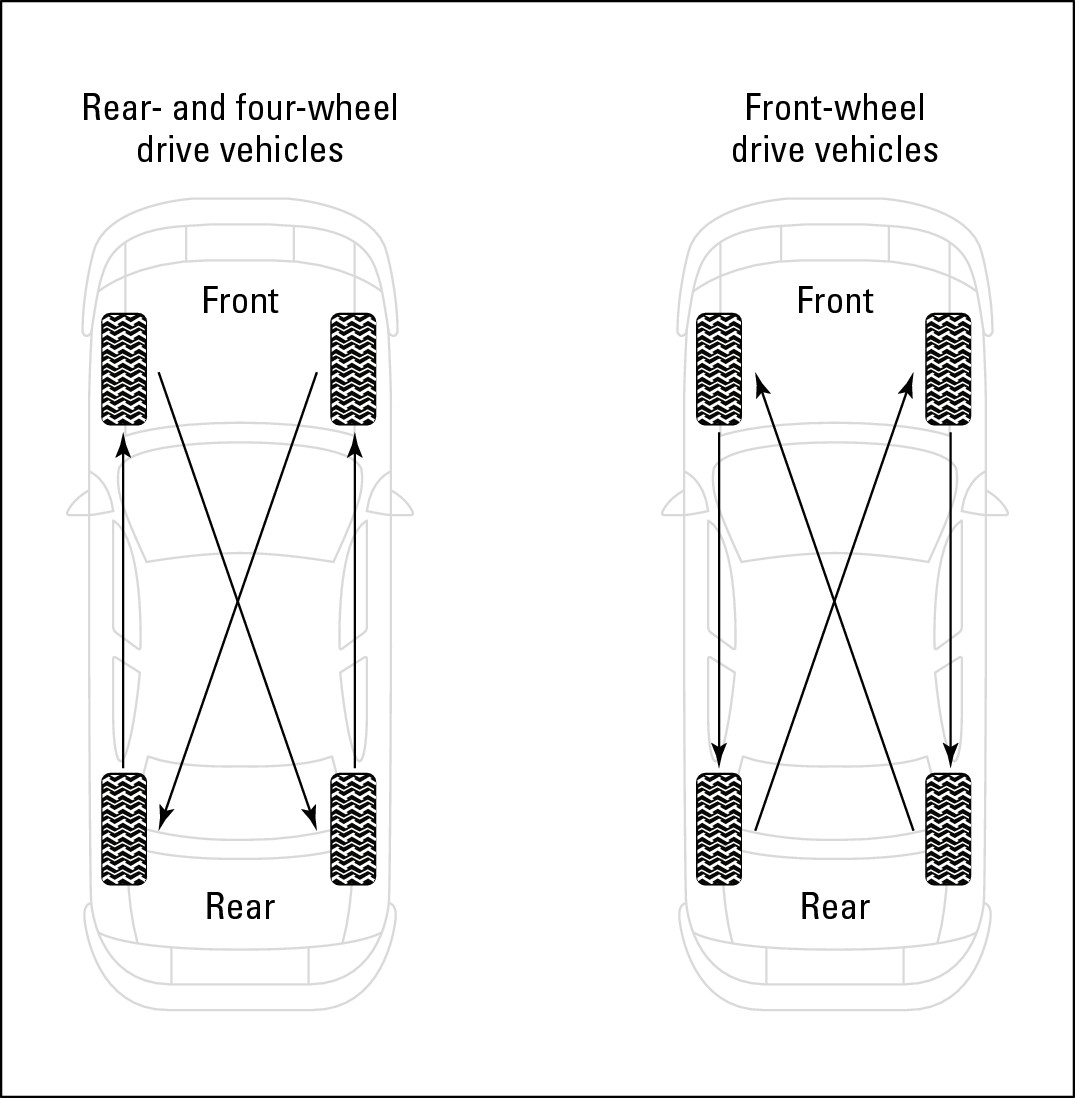

When you rotate tires, you simply move each tire from one location to another. However, where you move the tires depends on the type of tires and vehicle you have (see Figure 17-4). If you’re not sure where to move the tires on your vehicle, consult your owner’s manual (usually it has a diagram showing how the tires should be rotated), call the tire manufacturer, or ask the dealership.

|

Figure 17-4: How to rotate your tires. |

|

Adapted from the NHTSA (www.safercar.gov)

To save the enormous amount of effort involved in jacking up your vehicle and changing each tire, you can always just drive to a service facility and have them rotate the tires for you. Many shops include free tire rotation and wheel balancing in oil change and other special service promotions, and most tire dealers include periodic tire rotation and wheel balancing in their warranties. (I explain wheel balancing in the next section.)

Balancing your wheels

Wheel balancing does a lot to eliminate some of the principal causes of tire wear, and an unbalanced wheel and tire can create an annoying vibration on smooth roads. Because balancing is a job that should be done with the proper equipment, and because that equipment is costly, get the job done for you at a service facility or tire store. Just remember that there are two kinds of wheel balancing: static and dynamic.

Static balancing deals with the even distribution of weight around the

axle.

You can tell that you need to have your wheels statically balanced if a wheel (or more than one wheel) tends to rotate by itself when your vehicle is jacked up. It rotates because one part of the wheel is heavier than the rest. To correct this problem, a technician finds the heavy spot and applies tire weights to the opposite side of the heavy spot to balance it out.

Static balancing deals with the even distribution of weight around the

axle.

You can tell that you need to have your wheels statically balanced if a wheel (or more than one wheel) tends to rotate by itself when your vehicle is jacked up. It rotates because one part of the wheel is heavier than the rest. To correct this problem, a technician finds the heavy spot and applies tire weights to the opposite side of the heavy spot to balance it out.

Dynamic balancing deals with the even distribution of weight along the

spindle.

Wheels that aren’t balanced dynamically tend to wobble and wear more quickly. Because imbalance can be detected only when the tire is rotated and centrifugal force can act, correcting dynamic balance is a relatively complex procedure. Most service stations have computerized balancers that not only balance the wheels but also locate the places where tire weights are needed and decide how much weight to add.

Dynamic balancing deals with the even distribution of weight along the

spindle.

Wheels that aren’t balanced dynamically tend to wobble and wear more quickly. Because imbalance can be detected only when the tire is rotated and centrifugal force can act, correcting dynamic balance is a relatively complex procedure. Most service stations have computerized balancers that not only balance the wheels but also locate the places where tire weights are needed and decide how much weight to add.

Aligning your wheels

A cheap and easy way to substantially improve your vehicle’s handling and extend the life of your tires is to be alert to signs of misalignment and to have your wheels aligned immediately if the signs appear.

This job is sometimes called front-end alignment because the front wheels get out of line most often. They get that way because of hard driving with dramatic getaway starts and screeching stops, hitting curbs hard when parking or cornering, accidents, heavy loads, frequent driving over unpaved roads or into potholes, and normal wear and tear as the car gets older. Occasionally, the rear wheels need realignment as well. Vehicles with independent rear suspensions and front-wheel drive vehicles require four-wheel alignment. I used to think that alignment involved taking a car that had been bashed out of shape and literally pulling it back into line. Untrue. All the technicians do is adjust your wheels to make sure that they track in a nice, straight line when you drive. To do so, they use special equipment to check the following points:

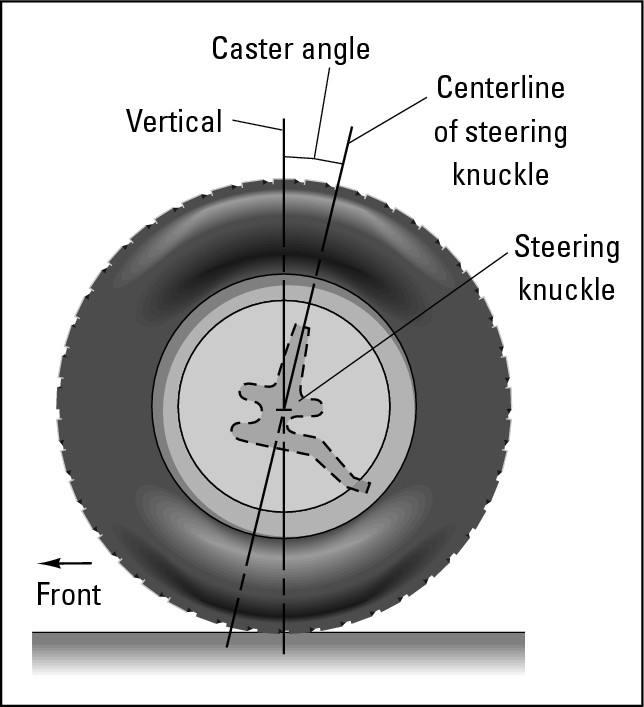

Caster:

Has to do with the position of your

steering knuckle

as compared to a vertical line when viewed from the side (see Figure 17-5). If properly adjusted, it makes your wheels track in a straight line instead of weaving or shimmying at high speeds. Caster also helps return the steering wheel to a straight-ahead position after completing a turn.

Caster:

Has to do with the position of your

steering knuckle

as compared to a vertical line when viewed from the side (see Figure 17-5). If properly adjusted, it makes your wheels track in a straight line instead of weaving or shimmying at high speeds. Caster also helps return the steering wheel to a straight-ahead position after completing a turn.

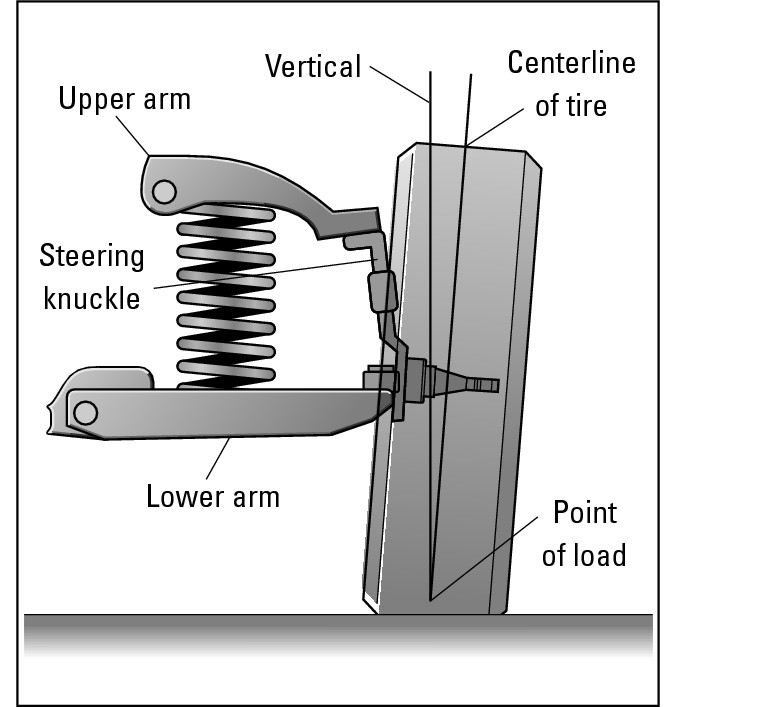

Camber:

The inward or outward tilt of the top of the wheels when viewed from the front/rear of the vehicle — in other words, how “bow-legged” or “knock-kneed” they are (see Figure 17-6). If the wheels don’t hang properly, your tires wear out more quickly, and your car is harder to handle.

Camber:

The inward or outward tilt of the top of the wheels when viewed from the front/rear of the vehicle — in other words, how “bow-legged” or “knock-kneed” they are (see Figure 17-6). If the wheels don’t hang properly, your tires wear out more quickly, and your car is harder to handle.

|

Figure 17-5: Caster. |

|

|

Figure 17-6: Camber. |

|

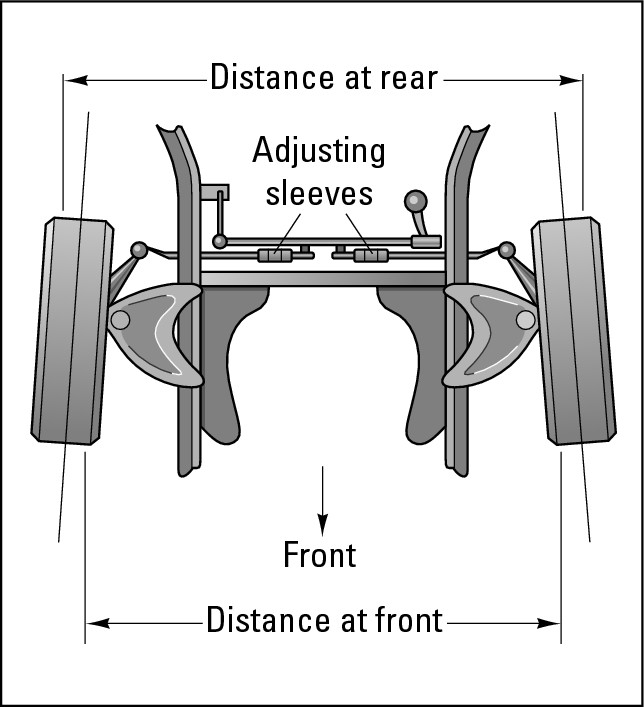

Toe-in

and

toe-out:

Involve placing your tires so that they’re properly positioned parallel to the frame when driving down the road. Some cars call for a little toe-in (tires pointing inward, as in Figure 17-7), whereas others are set with a little toe-out (tires pointing outward). The result should be a nice, straight track when the car is moving quickly. On some front-wheel drive vehicles, the manufacturer may set the rear tires with a little toe-in and the front tires with a little toe-out so that the tires are parallel to the frame when the vehicle is in motion.

Toe-in

and

toe-out:

Involve placing your tires so that they’re properly positioned parallel to the frame when driving down the road. Some cars call for a little toe-in (tires pointing inward, as in Figure 17-7), whereas others are set with a little toe-out (tires pointing outward). The result should be a nice, straight track when the car is moving quickly. On some front-wheel drive vehicles, the manufacturer may set the rear tires with a little toe-in and the front tires with a little toe-out so that the tires are parallel to the frame when the vehicle is in motion.

|

Figure 17-7: Toe-in. |

|

Turning radius:

The relation of one front wheel to the other on turns. If you turn to the right, the right front tire needs to turn at a slightly greater angle than the left front tire (see Figure 17-8). Your vehicle’s steering arms accommodate this feat. If your tires squeal sharply on turns, one of your car’s steering arms may be your problem.

Turning radius:

The relation of one front wheel to the other on turns. If you turn to the right, the right front tire needs to turn at a slightly greater angle than the left front tire (see Figure 17-8). Your vehicle’s steering arms accommodate this feat. If your tires squeal sharply on turns, one of your car’s steering arms may be your problem.

|

Figure 17-8: Turning radius. |

|

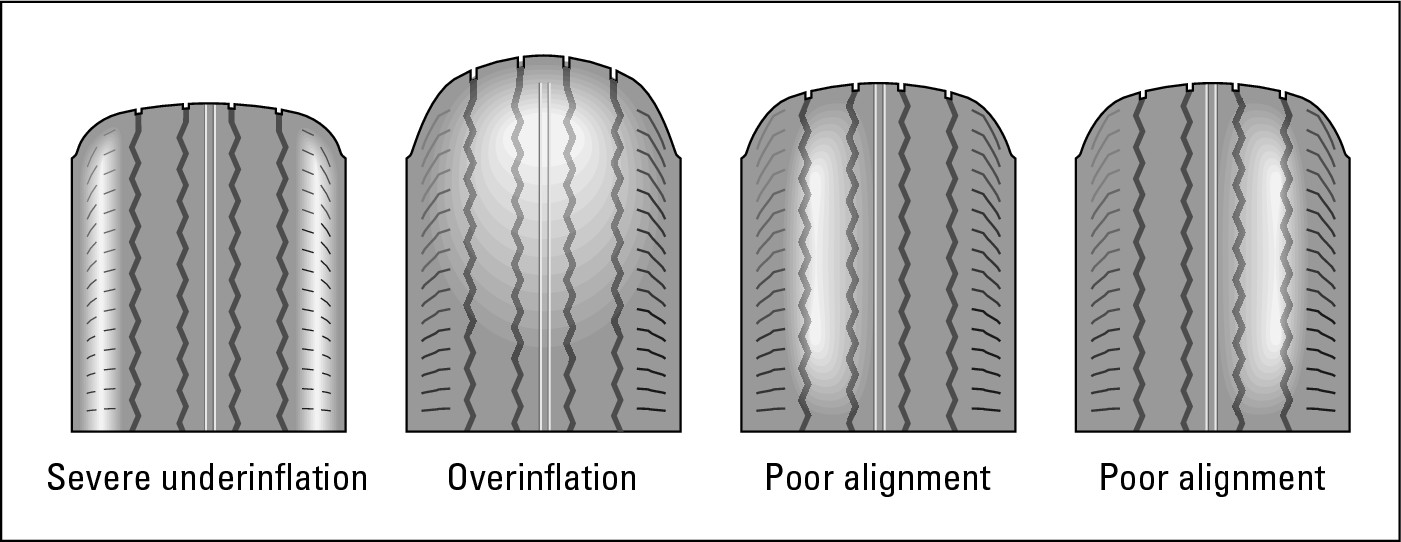

Checking your tires for wear

| Clue | Culprit | Remedy |

|---|---|---|

| Both edges worn | Underinflation | Add more air and check |

| for leaks | ||

| Center treads worn | Overinflation | Let air out to manufac |

| turer’s specifications | ||

| One-sided wear | Poor alignment | Have wheels aligned |

| Treads worn unevenly, with | Wheel imbalance | Have wheels balanced |

| bald spots, cups, or scallops | and/or poor alignment | and aligned |

| Erratically spaced bald spots | Wheel imbalance or | Have wheels balanced |

| worn shocks | or replace shocks | |

| Edges of front tires only worn | Taking curves too fast | Slow down! |

| Saw-toothed wear pattern | Poor alignment | Have wheels aligned |

| Whining, thumping, and other | Poor alignment or | Have wheels aligned or |

| weird noises | worn tires or shocks | buy new tires or shocks |

| Squealing on curves | Poor alignment or | Check wear on treads |

| underinflation | and act accordingly |

|

Figure 17-9: What the signs of poor treadwear mean. |

|

To determine what’s causing problems with your tires, try the following:

Look for things embedded in each tire. Do you see nails, stones, or other debris embedded in the treads? Remove them. But if you’re going to remove a nail, first make sure that your spare tire is inflated and in usable shape.

Look for things embedded in each tire. Do you see nails, stones, or other debris embedded in the treads? Remove them. But if you’re going to remove a nail, first make sure that your spare tire is inflated and in usable shape.

.jpg)

If you hear a hissing sound when you pull a nail, push the nail back in quickly and take the tire to be fixed. If you aren’t sure whether air is escaping, put some soapy water on the hole and look for the bubbles made by escaping air. If you’re still not sure whether the nail may have caused a leak, check your air pressure and then check it again the next day to see whether it’s lower (for help, see “Checking tire inflation pressure” earlier in this chapter). Tires with leaks should be patched by a professional. If the leak persists, get a new tire. These instructions apply to any sharp object that may have penetrated through the tread.

Look at the sidewalls. Check for deeply scuffed or worn areas, bulges or bubbles, small slits, or holes. Do the tires fit evenly and snugly around the wheel rims?

Look at the sidewalls. Check for deeply scuffed or worn areas, bulges or bubbles, small slits, or holes. Do the tires fit evenly and snugly around the wheel rims?

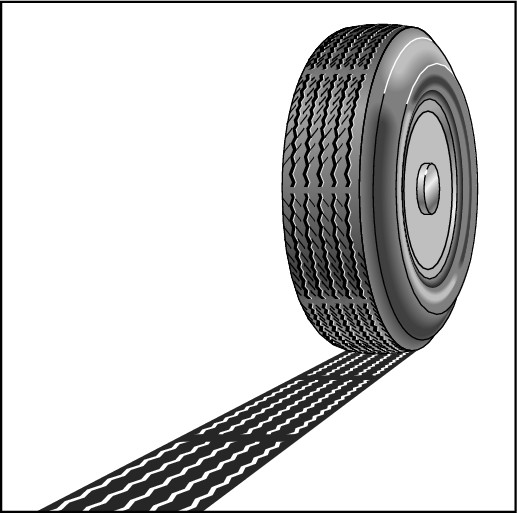

Look at the treads. Most tires have built-in

treadwear indicators

(see Figure 17-10). These bars of hard rubber are normally invisible but appear across treads that have been worn down to 2/32 of an inch of the surface of the tire (the legal limit in most states). If these indicators appear in two or three different places less than 120 degrees apart on the circumference of the tire, replace the tire.

Look at the treads. Most tires have built-in

treadwear indicators

(see Figure 17-10). These bars of hard rubber are normally invisible but appear across treads that have been worn down to 2/32 of an inch of the surface of the tire (the legal limit in most states). If these indicators appear in two or three different places less than 120 degrees apart on the circumference of the tire, replace the tire.

|

Figure 17-10: It’s time for new tires when treadwear indicators appear. |

|

If your tires don’t show these indicators and you think that they may be worn below legal tolerances, place a Lincoln penny head-down in the groove between the treads. If you can see the top of Lincoln’s head, your tire probably needs to be replaced.

To measure treadwear more precisely, place a thin ruler into the tread and measure the distance from the base of the tread to the surface. It should be more than 2/32 inch deep. ( Note: If your front tires are more worn than your rear ones and show abnormal wear patterns, you probably need to have your wheels aligned.)

.jpg)

Sometimes 2/32 inch of tread isn’t enough to keep you safe. If you live in a rainy area, measure the depth of your treads with a quarter rather than a penny, using Washington’s hair to see if your tires have at least 4/32 inch of tread remaining, which reduces the distance and time it takes for the car to stop.

Pay attention to leaks. If you keep losing air in your tires, have your local service station check them for leaks. Sometimes an ill-fitting rim causes a leak. The service facility has a machine that can fix this problem easily.

Pay attention to leaks. If you keep losing air in your tires, have your local service station check them for leaks. Sometimes an ill-fitting rim causes a leak. The service facility has a machine that can fix this problem easily.

If the facility can’t find a leak, your rims fit properly, and you’re still losing air, you probably have a faulty tire valve that’s allowing air to escape. If a tire valve needs to be replaced, be sure that the replacement provided by the service facility has the same number molded into its base as the valve it’s replacing.

Dealing with Defective Tires

Tires, like vehicles, can turn out to be lemons. But these lemons can put your life on the line. Defective tires should be replaced by the manufacturer, but you may need proof before you file a complaint. If you discover that one of your tires is defective, go to www.safercars.gov/tires/pages/TireDefects.htm for links that enable you to check for recalls; check for complaints by make, model, and year; and search to see whether a safety investigation is underway into defects found on a particular tire (there may be fees for this search, however). You can file a complaint at www-odi.nhtsa.dot.gov/ivoq/index.cfm.

If you prefer, you can call the Vehicle Safety Hotline toll free at 1-888-327-4236 to report safety defects and to obtain information on cars, trucks, child seats, and highway or traffic safety.