RURAL DISCONTENT

The sheer size of China’s rural population is one of its most arresting features: 737 million people, close to two and a half times the total population of the United States. Even when it was only a third of its present size during the civil war, China’s rural population was recognized by Mao Zedong as a singular resource that could give the Communist Party the leverage it needed to defeat the city-based forces of the Nationalist Party. And so he set aside the conventional Marxist-Leninist canon and focused his attention on peasant grievances: their desperate poverty and their concern about the depredations committed by the Japanese forces seizing and occupying so much of China’s territory. Attending to these concerns, the Chinese Communists mobilized their overwhelming social force and with the help of the peasantry brought about the victory of the Communist revolution in 1949.

By means of land reform and the creation of collective farms in the years immediately following the Communist victory, rural incomes were equalized and raised. But in other ways, the, exploitation of the rural population continued. Keeping the price it paid for grain artificially low, the government turned a profit at the expense of the peasantry and then used this profit as the source of capital for industrializing China’s cities; city dwellers also got government subsidies for housing and food that were unavailable to the rural majority. In the twenty-five years prior to the reform period, per capita income, in the countryside increased less than 50 percent. Moreover, it was the rural population that suffered the most serious consequences of

China’s disastrously misguided agricultural policies during the late 1950s, policies that resulted in more than twenty million deaths from starvation in rural villages throughout the country.

Deng Xiaoping began his economic reforms in the countryside for two reasons: he knew that reforming agriculture would be much easier than reforming industry, and if the reform of agriculture were successful, he could use that success to persuade his skeptical colleagues to take on the more complicated tasks of reforming industry.

Indispensable to the success of agricultural reform was the household responsibility system, which had originated as an experiment in the early 1960s, when Deng and his colleagues were looking for ways to alleviate the disaster brought on by the Maoist excesses of the Great Leap Forward in the late 1950s. In the experiment, land was taken out of the collective and given to households to farm; what any one household produced over the quota set by the local government, it was permitted to sell on the rural free market. The experiment had been successful, but it was abandoned once the disaster abated, and Mao later denounced it as unacceptably capitalist in spirit.

The household responsibility system was resurrected in 1978, once again as an experiment in one or two locations. But almost overnight it was adopted by farming communities throughout China. The incentives it incorporated quickly boosted productivity, output, and household income. When these increments began to slow seven years later, a further round of reform stabilized the contract system and opened the door to the proliferation of small-scale industry in the rural economy.

The combined effect of these reforms was to raise rural incomes by a factor of three over the first twelve years of the reform period. A lot of publicity was given to the first “ten thousand kuai households” (households whose annual income had reached twelve hundred dollars). When news of this new phenomenon reached city residents, they found themselves envious of their country cousins for the first time in memory and were more than ready to see replicated in the city some of the entrepreneurial opportunities available beyond the suburbs. And given their significantly improved standard of living,

China’s rural residents were generally quite satisfied with their lot at the end of the 1980s. They were somewhat insulated from the inflation that loomed large in the cities, and corruption, the second most frequent complaint of city dwellers, had yet to become fully visible in rural communities. This helps explain why the slogans and speeches of students and workers who rushed into the streets of every major city in China in the spring of 1989 fell on deaf ears in the countryside, why there was so little sympathy among country folk for the demonstrators’ demands, and why the demonstrators made virtually no effort to arouse the support of people living outside the cities.

During the 1990s this quiescent satisfaction in the rural community disappeared. Urban reforms eliminated the small entrepreneurial advantages that rural residents enjoyed over their urban compatriots, and today the gap between rural and urban living standards is growing rapidly. The rural majority is reacting to this situation in two ways: they are taking advantage of the relaxed restrictions on geographical mobility in record numbers, and as we have seen, some 150 million underemployed workers have left their rural homes in search of temporary work in China’s largest cities. Those who have stayed in the countryside are nursing their grievances and, increasingly, acting on them. Given their new attitudes and habits, it seems unlikely that they will sit on the sidelines the next time political dissatisfactions spill into China’s streets.

During the first years after the Communist revolution, ownership of land and equipment and the power to make decisions about production were removed from individual households and vested in progressively larger and larger units: first mutual assistance teams, then two stages of cooperatives, and finally communes. In this process, the size of the decision-making unit in the rural economy grew from a household to an entity encompassing, on average, more than five thousand households. Communes typically incorporated the people of what had been several villages before collectivization began. The commune was divided into brigades, each made up of a population

roughly equal to that of the average village, or about two hundred households; the brigades in turn were divided into production teams of twenty to forty households. The production team or, in some cases, the brigade held title to the land and equipment for which it was responsible; members received their work assignments from the production team leader. Individual householders owned their houses (but not the land on which the houses were built) and personal effects and had use rights to a “private plot” of land on which produce or animals could be raised for home consumption or for sale on the rural free markets.

Compensation within the commune system was based on work points. Work points were assigned on the basis of the difficulty of the task, the capability of the worker, and the amount of time spent at work. Men, who were considered more capable than women at working the land, routinely received more work points than women for performing the same task for the same period of time. After the harvest, grain was sold to the state according to predetermined quotas, and work points were totaled; whatever amount of the team’s profit it had agreed to set aside for compensation was then divided by the total number of work points earned by all the team members. This fixed the value of the work point, and team members then received compensation based on their total points. Only the largest, richest communes could offer their members retirement plans, but all of them offered medical care and primary education at nominal cost.

This compensation system gave peasant households fairly secure, if very low, incomes, but it provided no incentive to work hard or efficiently, and Chinese agricultural production was essentially stagnant. Productivity was very low, and the growth in total output did not keep up with the growth in population.

But after the failure of the Great Leap Forward, this process was reversed. Beginning in 1959, ownership and decision making were shifted downward, first to the brigade and subsequently to the production team. The cycle was completed with the reintroduction of the household responsibility system in 1978. With it, the individual household was reempowered and once again serves as the locus of production decision making and de facto landownership.

Village governments, which took the place of production team management groups, put the new system in place. They evaluated their land and divided it into parcels, each parcel containing noncontiguous pieces of good land and less productive land. Households were allowed to bid for use rights on these parcels; better-off families with more able-bodied workers were rewarded with use rights to the larger, better parcels. Team implements and draft animals were sold at auction to householders.

The village authorities and successful bidders signed contracts that stipulated three “fixed items”: the price the household would pay for inputs, including seed and fertilizer, which were rationed on the basis of the size of the contracted parcels; the expected output of specific commodities, such as grain or cotton, to be produced on the parcels; and the price the state would pay for the contracted commodities. The initial contracts were written for one-year terms. Everything the household produced over and above the stipulated amount of the stipulated commodity it was free to dispose of as it chose—whether for personal consumption, barter, or sale. Sales could be made either to the state at a price higher than that paid for contract commodities or directly to consumers on the free market.

The rural working community responded to this new system’s incentive for hard and efficient work. The increase in grain production was modest, but total agricultural output grew significantly. The average annual increase in the total amount of grain produced from 1970 to 1977 was 3.6 percent; it rose during the seven years following the introduction of the responsibility system to 5.5 percent; comparable figures for the total income from agricultural production are 3.1 percent and 13.9 percent. These figures reflect the fact that the contract system, which encouraged farmers to diversify their crops, led to the cultivation of fruit and vegetables, which were more profitable than grain.

Bringing industry to China’s countryside was a goal that Mao pursued during the last twenty years of his life. He saw a number of advantages in doing so: peasants would be proletarianized by exposure to the industrial workplace; rusticating industry would bring factories closer to their source of supply and to the rural consumer;

and China’s national defense would be enhanced by making each part of the country more self-sufficient, so that the occupation or destruction of one area would not affect the economic viability of the rest of the country. Finally, opening up factories in the countryside would absorb the substantial surplus labor power in the rural economy.

The first step in introducing industrial practices into the rural community came during the Great Leap Forward, with the creation of what were called backyard steel furnaces. Rural residents, like their urban compatriots, were encouraged to collect scrap metal (along with useful tools and utensils that were declared scrap in order to reach the inflated goals of the campaign) and to melt it down to help increase the nation’s steel output. The campaign was a failure on all counts. Few proletarianizing lessons could be learned in these ad hoc workplaces, and the lumps of melted metal produced in them were largely unusable.

Alongside the useless steel furnaces, however, workshops and small factories were set up that began the process of creating a “cellular” economy in rural China. During the 1960s and into the 1970s a major effort was launched to open new factories and to make China’s more than two thousand counties as self-sufficient as possible. Some of these factories belonged to the state sector, many were owned and managed by the county government, and others were owned and managed by individual communes. In the mid-1970s rural small-scale industry was producing about 10 percent of China’s total industrial output; in certain lines, such as chemical fertilizer and cement, the small-scale factories accounted for more than half the nation’s total production. As we shall see, these efforts were augmented by the army, which was also active in building a “third line” of factories in remote areas.

The most recent wave of rural industrialization began in the mid-1980s, when the initial surge of growth in rural per capita income brought on by the introduction of the responsibility system had begun to slow. Reformers now encouraged a rapid proliferation of new industrial enterprises nominally under township and village ownership but actually privately financed and managed. These enterprises,

the assets of the majority of them having been transferred through “insider privatization” to private hands, have a workforce of 140 million and, in 1996, had come to account for 40 percent of China’s industrial output, producing both for the domestic market and for export.

Unfortunately, there are negative consequences of this otherwise promising development. The little factories occupy what was once arable land and contribute to air and water pollution. Built with the lowest possible capitalization, very few of them conform to China’s environmental protection regulations. Local officials eager to reap the benefits of rapid industrialization put pressure on the environmental protection officials to ignore violations or to grant waivers. In the trenches where the war between economic development and environmental protection is being fought, economic development is winning most of the battles.

The household responsibility system increased farmers’ productivity through monetary incentives. But the smallness of the contracted parcels—the average plot was no larger than two acres—severely limited the ultimate productivity of the agricultural sector. With the adoption of a new landownership law in the fall of 2008, talk of rationalizing agricultural production by combining small contracted plots into larger, more efficient farms grew louder.

Some consolidation of parcels has occurred spontaneously. In some places, households pool their parcels, labor, tools, and animals and farm the land as informally constituted cooperatives. The new land law effectively extends to the countryside the thriving real estate market currently functioning in the cities. With use rights contracts transferable, holders can sell their contracts and leave agriculture entirely. Others can buy up these contracts, hire a staff of farm laborers, and become large-scale agricultural producers, who can realize economies of scale with respect to such inputs as chemical fertilizer and insecticides. But large, efficient farms turn underemployed farm workers into unemployed ones. Their need for jobs frequently encourages local authorities to build more factories, which take badly needed arable land out of cultivation, thereby reducing total production.

Chinese economists estimate that as many as 200 million rural workers—40 percent of the total rural workforce—are either unemployed or underemployed. This situation, taken together with environmental degradation in the countryside, about which we shall talk later, are the direct causes of the outflow of 150 million people into China’s major cities as migrant laborers. As noted earlier, the conditions under which migrants work are far from ideal. Nonetheless, they send home, on average, close to one thousand dollars a year, much more than the average rural household income. The social consequences of their absence from the rural communities are serious, however. There is, in effect, a missing generation in many Chinese villages, and grandparents are obliged to care for children whose parents have left for work in the city. For a year or so in 2005 and 2006 there appeared to be a shortfall of as much as 10 percent in the migrant workforce in Guangdong and Fujian, and some factory owners resorted to recruiting visits to the countryside. With the worldwide economic downturn, however, close to seventy thousand factories across the country closed down, resulting in 1 in 7 migrant workers’ being laid off and 20 million of them returning to the countryside.

The household registration, or hukou, laws in China that classified everyone as either an agricultural worker or a nonagricultural worker rendered rural workers second-class citizens—“racial discrimination with Chinese characteristics,” as Li Xiangen, an itinerant fountain pen repairman, characterized it in a letter to his local newspaper. “‘Farmer’ shouldn’t be a label, it should be a profession like any other, which people have the freedom to leave,” Mr. Li said in an interview with a New York Times reporter. As we have seen, a new law enacted in 2005 abolished the occupational categories while retaining the geographical categories and devolving to local governments the authority to grant urban residency to newcomers from the countryside—an authority they are highly unlikely to use frequently.

Now that the urban economy is beginning to rebound from its slump, rural workers are returning to their urban places of employment. Looking ahead, Chinese planners have a much more ambitious

goal in mind, that of shifting the rural and urban population ratio from its current 55:45 to something approaching 30:70, a ratio more typical of advanced developing countries. This they expect to accomplish only in part by enlarging the population of the country’s largest cities. Much of the urbanization of the population will come as a result of transforming existing rural villages and small towns into metropolitan centers. Facilities and services will be needed for the more than five hundred million people to be relocated into these new cities. The purpose behind this radical social restructuring is to transfer rural Chinese underemployed workers into industries based in the countryside. Moreover, it is proposed that once this plan has been implemented, rural town governments will take responsibility for administration of their neighboring townships; since there are roughly half as many towns as townships, this consolidation means that the lowest level of rural administration will be twice its current size.

The task of ensuring a sufficient food supply for the Chinese people is the first priority for those responsible for guiding China’s rural economy. The task is best thought of as a fraction, with the numerator food supply and the denominator population, the aim being to increase the numerator as much as possible while controlling the growth of the denominator.

The first aspect of this task is to ensure a steady increase in the production of grain, cotton, and other agricultural commodities, without which the Chinese economy would grind to a halt. The market solution—raising the price paid to farmers to encourage them to produce more—threatened to create as many new problems as it solved old ones. Under the commune system, farmers had little or no choice of what to grow, to whom to sell their produce, and at what price. Natural disasters and sloth were the only obstacles to the state’s realizing its quotas each year. Natural disasters are a constant, of course; reform policies largely eliminated sloth by means of material incentives. But these same policies created a new hurdle

for the government to surmount: producing the basic agricultural commodities became a money-losing proposition for the farmers. Almost anything the rural household planted on its contracted land would yield a better income than grain, given the prevailing prices the state was willing to pay for it.

The situation is comparable in cotton production. Raising cotton on contracted land and selling it to the state at the state’s artificially low price produced only about one-fifth of the income that vegetables brought in. Peasants obliged by contract to grow cotton took to selling it on the black market for three times the state’s price and claiming a shortfall in the harvest when state purchasers came to claim their contracted amount. Were the government to have raised cotton prices, it would have increased costs for the textile plants, most of which were state-owned enterprises already teetering on the brink of bankruptcy.

As part of its package of perquisites for city dwellers, China in years past purchased grain well below market prices, then sold it in the cities at an even lower price, absorbing the difference as an expense item in the national budget. Similarly, as part of the package of subsidies for state-owned textile factories, cotton was purchased at below-market prices from the farmer and sold to factories at an even lower price. When these expense items grew, the state decided no longer to subsidize grain and cotton and to allow prices to rise to market levels: in 1994 the price of grain in city markets rose by 50 percent, and the following year another 30 percent, a major factor in driving the urban inflation rate to 25 percent in 1994 and 17 percent in 1995. Meanwhile, the price of cotton increased 60 percent in 1994 and another 30 percent in 1995, thereby exacerbating the already precarious fiscal health of the textile industry.

These radical measures (abetted by favorable weather) appear to have been effective. Grain production reached a record output of 508 million tons in 1999, and although it declined to 435 million tons in 2003, it reached a new record of 528 million tons in 2008. Cotton production, too, has increased since 2003 at a rate of more than 10 percent per year. Meanwhile, the runaway inflation of the

mid-1990s has been brought under control, and grain prices in the cities have stabilized at a level approximately 75 percent higher than that of 1994.

Increasing the numerator of the food supply to population ratio is all the more difficult because of the declining supply of arable land. Every day decisions made in rural communities reduce the already scarce amount of land available for cultivation. As we have seen, China has about 20 percent of the world’s population and only about 7 percent of its arable land—currently about 350,000 square miles, 78 percent of the 1950 figure. This means that over the past five decades China has endured a net annual loss of about 2,000 square miles despite its vigorous efforts at reclamation, and the rate at which land has been taken out of cultivation since the reforms began is about five times that average.

Yet land is being withdrawn from cultivation for what are in theory good causes. Rural factories produce goods that augment the gross national product and give jobs to workers who would otherwise leave the countryside or be unemployed. But factories occupy land that could be cultivated, and they need raw materials and markets; that means expanding the highway and rail network, eating up still more land. As rural incomes rise, people are eager to expand their living quarters, and although local regulations restrict the proportion of land in a community that can be devoted to housing, these are often stretched or violated. Land is also taken out of cultivation for uses with little or no value for economic development. Many odd schemes have proliferated recently; the most egregious of these are two dozen golf courses laid out in 1994.

There is another problem. Striving for grain self-sufficiency in China requires that grain be grown in areas that require extensive irrigation. The North China Plain, for example, which produces half the country’s wheat, is experiencing a serious drain on its underground water. Some argue that grain production in areas like the North China Plain should be restricted to preserve China’s very scarce water reserves.

In the mid-1990s some foreign demographers and agronomists issued dire predictions about China’s ability to feed its population

over the next thirty years. Given the current growth rate of the Chinese population and its changes in diet, they estimated that it would take more than 600 million tons of grain to feed that population in 2030. Not only will there be more people to feed, but as household income increases, so does consumption of meat, poultry, and eggs. Grain production in 1998 reached what was then the record level of 486 million tons. To reach 6(10 million tons by 2030, production must increase annually by 3 million tons. But with land being taken out of cultivation more and more quickly in the late 1980s, conservative projections showed a drop in grain output over the next thirty-five years that would result in a grain deficit of more than 300 million tons in 2030. The total world grain surplus available for export in 1993 was only about 220 million tons, and many other countries are dependent on that surplus. “What will happen when China becomes a grain importer on a massive scale?” they asked.

The Chinese government at first ignored these dire predictions, then began to take them very seriously. A land use law that came into effect at the beginning of 1999 severely restricts the conditions under which land can be taken out of cultivation. Transfers of up to eighty acres of agricultural land to nonagricultural use are subject to approval by provincial authorities; transfers of more than eighty acres are subject to approval by the central government. Land taken out of cultivation must be compensated for by an equal amount of land reclaimed. Speaking directly to the question of China’s grain self-sufficiency, Chinese agronomists pointed out that not only is the country very close to completely self-sufficient in grain, but average annual per capita grain consumption, at 320 pounds, exceeds the world average, as does per unit grain output, at 1.8 tons per acre.

Optimists in Beijing assume that these measures to increase grain production will result in continuing growth rather than a decline in grain production over the next twenty years; state planners project an annual increase of between 2 and 3 million tons to a level of just over 600 million tons. They estimate the need for grain at some 630 million tons in 2030 and argue that imports should be relied on to make up the shortfall of 30 million tons. (In 2008 the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development projected

that China’s grain imports would reach 12 million tons, or about 4 percent of total world imports of about 284 million tons.)

If the dire predictions were overly pessimistic, these new Chinese government projections seem overly optimistic, given the difficulties in enforcing the new land use law and the strong economic incentives to disobey it, as well as the lingering economic disincentives to devote land and labor to grain rather than to more lucrative crops or enterprises.

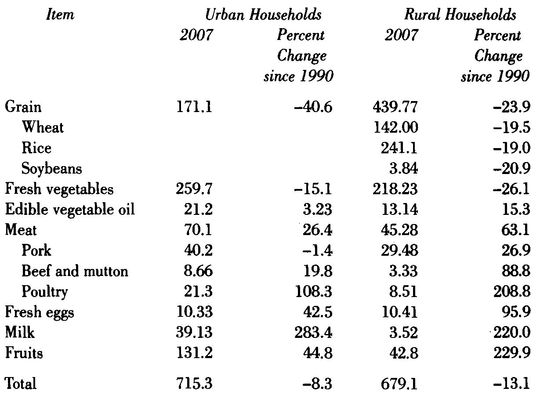

It is important to take into account the fact that the diets of both rural and urban residents have changed in recent years. As the following table shows, grain and fresh vegetable consumption is down for both communities, their place in the diet being taken by meat (particularly poultry), eggs, milk, and fruit.

Table 10: PER CAPITA ANNUAL PURCHASES OF MAJOR COMMODITIES (in pounds)

(Source: China Statistical Yearbook 2008. Note that the data show pounds of food consumed, not calorie intake.)

The substantial growth in milk consumption became an issue when, in the fall of 2008, it was discovered that the milk supply, including infant formula, and some eggs were tainted with melamine, a chemical additive that mimics protein. Six infants died of kidney failure caused by the tainted milk, and more than three hundred thousand others were sickened before the milk was withdrawn from the market. The owner of the Sanlu Group, the largest of several milk producers involved in the episode, pleaded guilty to having withheld knowledge of the scandal for more than three months and was sentenced to life in jail.

The goal of controlling the growth of the denominator of the food supply to population ratio is equally daunting. China’s efforts to limit population growth to one child per family have fallen short of their target. The average number of children in China’s cities is very close to 1 per family, but the national average is 1.84. Rural resistance to the birth control program is attributable, on the one hand, to tradition, which dictates a preference for a male heir to carry on the family name (multiple births in one family frequently being the result of repeated attempts to have a male child), and, on the other hand, to the economics of the rural reforms. The household responsibility system rewards big families in which there are many workers. Because girls cease to contribute to their parents’ exchequer once they marry and leave the household, boys are considered a better source of income. And since there are no retirement plans in the vast majority of rural collectives, a couple’s only source of old-age security is a large family. The birth control program is successful in the Chinese countryside only when it is enforced with such harsh measures as forced abortions or sterilizations and the destruction of homes and property. But such measures further alienate the peasant community.

Rural people have as many reasons to be dissatisfied with their government as the government has to be dissatisfied with them. They face more and more problems that local authorities are unwilling to address or unable to resolve. In some instances the local authorities themselves are the problem.

With the introduction of the responsibility system came a structural change in rural administration in which the township took the place of the commune as the lowest level in the government structure. On average, each township is approximately twice the size of a former commune, and its administration serves as the local government, supervising the civic life of the two dozen or so villages under its authority, and, in the early stages of rural industrialization, as a production company, overseeing numerous collective enterprises (the average township had more than seven hundred of these). The production company was organized into agricultural and industrial departments and perhaps others with responsibility for commercial activities, transportation, and the like. With the privatization of township enterprises the local government has assumed the role of regulating, rather than owning and managing, the elements of its nonagricultural economy.

Meanwhile, as we have seen, the countryside is the site of “creeping democratization.” Beginning in the late 1990s, elections have been held on an experimental basis at the village level. A village committee of three to seven members is directly elected on the basis of open nominations. While the authority of the committee is limited, voter turnout is typically high. Village elections were sanctioned in a new law adopted by the National People’s Congress in 1998. By 2000 more than half of China’s one million villages had elected committees, and the experiment had been extended to the township level.

Among the most serious sources of dissatisfaction are excessive taxes and fees. County and township governments are seriously underfunded by the central government for the national mandates they are expected to carry out. A Central Committee document in 2005 decreed that the agricultural tax imposed on rural households, previously capped at 5 percent, would be eliminated in twenty-four provinces that year and in the remainder of the country over the next several years. That promised to return to rural household exchequers $4 billion, or about $5.60 per rural resident per year. In practice,

however, the agricultural tax is the least of the fiscal burdens borne by rural residents. Local officials impose fees, tolls, fines, special levies, and charges that in most areas add up to 15 percent or more of household income, in some cases as high as 50 percent or more. Several years ago a New York Times reporter described the personal finances of Li Yongrong, a peasant in Anhui Province. Li realized $700 each year from farming his four-acre plot; but local government fees absorbed $600 of that, and school fees for his two teenage children took another $300. He makes up the deficit by using his Flying Tiger pickup (purchased with $2,000 in loans and savings) to provide transport services to his neighbors.

Were this local government revenue used to pay for public services and improved infrastructure, rural taxpayers would no doubt continue to grumble but would at least enjoy some benefit. In fact a substantial proportion of the tax revenues goes into the personal accounts of local officials, along with their take from bribes and profiteering. All too often this ill-gotten gain is consumed in conspicuous displays of personal excess—lavish banquets, expensive automobiles—that only inflame resentment. Indeed, this corruption is itself a potentially explosive source of rural discontent. Those who lived through the final days of the Nationalist government in the 1940s—days marked by rampant corruption—claim that the situation is worse now than it was then.

In 2004 a husband-and-wife team of investigative reporters in Anhui published An Investigation of China’s Peasants.1 They describe the nightmarish situation in which rural residents find themselves when they decide to protest the malfeasance of local officials. Once they travel to the township or county level to describe the illegal extortion they have experienced they learn that officials at those levels are operating in cahoots with the local bullies, and suddenly it is the protesters who are treated as criminals and subjected to arrest

and violent retribution. In what is perhaps the most notorious of their stories, Granny Gao, an elderly resident of Gao Village, had the temerity to protest the fact that she had been double taxed on her house site. The village chief first struck the woman, then ransacked her house and furniture. Next he took the case to his superiors, who returned to the village to arrest Granny Gao and ten of her supporters for tax evasion. Realizing the villagers were caught in a web of official collusion, one resident of a nearby village decided to use the vehicle of petition and took Granny Gao’s case to Beijing—twice—without gaining satisfaction. The village chief remained in office, unscathed.

In addition to graft over taxes and fees, a second major bone of contention among rural residents is what amounts to the confiscation of their land with insufficient or no compensation. Until the new land law was passed in 2008, farmland could not be bought or sold. Seeking to develop the land for nonagricultural purposes, local authorities had to reclaim the land from use rights contract holders and rezone it for commercial purposes. While peasants were entitled for compensation for their contract rights—and now for the land itself—if they receive compensation at all, it virtually never approaches the profit the local government authorities realize from the subsequent development of the land. Some seventy million farmers—a number soon expected to reach one hundred million—have lost their land in this fashion over the last decade, and some 5 percent of arable land has been involved in these transfers. Speaking in 2006, Premier Wen Jiabao spoke of these “land grabs” as “a historic error” that could threaten national stability.

Though perhaps not felt by rural residents in their daily lives, the gap between rural and urban incomes may be the most serious source of dissatisfaction over the long term. For a brief time in the early 1980s, economic reforms in the countryside resulted in the incomes of rural households growing much faster than those of urban households: in 1980 rural incomes were only one-third of urban incomes; by 1985, when reform of the urban economy began, they had

at least grown to one-half of the average urban income. But after 1985 the gap began to widen again. At this point the gap stands once again at 1:3.3; in monetary terms, it is forty-six times what it was in 1978. Using the Gini coefficient to measure income inequality, China currently stands at 46.9 (the U.S. score is 40.8; the lowest Gini coefficients, meaning the most equal distribution of income, are found in Denmark at 24.7 and Japan at 24.9).

The average urban per capita income in China’s cities stands at just over $2,000 per year; the average rural per capita income is somewhat less than $605 per year. Twenty-three percent of the Chinese population is living in poverty (defined by the World Bank as a per capita income of less than $456 per year), and the vast majority of these are rural residents. And the situation is getting worse. The overall growth rate in the urban economy is more than 10 percent, and in the rural sector only about 4 percent.

In the past this rural and urban gap didn’t matter a great deal. The state’s control over the flow of information and the almost complete absence of geographical mobility meant that much of China’s rural population was ignorant of city conditions, and even if they were aware of the differences in living standards, there was nothing they could do. Today the situation is very different. Information about conditions in China’s most highly developed cities is trumpeted in the official media, and the vast majority of rural families have one or more members who are migrant workers temporarily living in cities.

Another aspect of the rural and urban gap, of which individual farmers may be less aware but which seriously jeopardizes their long-term interests, is that the rate of capital investment in the industrial sector is substantially higher than that in the agricultural sector. In the early days of the People’s Republic, it was very different: investment in agriculture constituted nearly a quarter of total investment in China in the late 1950s and early 1960s. By the late 1990s, however, that proportion had dropped to 2 percent, the rationale being that the rural collective sector, powered by reforms, was generating enough capital to allow local governments to take over agricultural investment. The fact of the matter is, however, that

this local government investment also declined precipitously during the 1980s, from nearly 40 percent of total local investment to under 10 percent by the end of the decade. Seeking a high return on each investment dollar, local governments are much more inclined to invest in new industries or even real estate development than to settle for agriculture’s low return.

Recognizing the problem of insufficient investment in agriculture at all levels of government, in his “state of the union” address at the 2004 meeting of the National People’s Congress, Premier Wen Jiabao pledged an increased investment in the agricultural sector of $3.6 billion. A comparable pledge was included in Central Committee Document No. 1 in 2008, and the $586 billion stimulus package announced in the fall of that year includes infrastructure projects that will benefit the rural economy.

Several other problems have caused China’s rural residents to lose confidence in their local governments. Environmental pollution is one of them. People in the countryside are the first to suffer when township and village industrial enterprises flout air and water pollution regulations. Until very recently China had no grassroots “green” movement pressuring the government to address these matters, but there are signs that a citizens’ movement with an interest in improving environmental quality is coming together.

Also, crime is on the rise throughout China, and one form of violent crime endemic in the countryside is the abduction of women and of male children, the women to be sold as wives or prostitutes, the boys to be sold to families who have not produced a male heir, and children of both sexes kidnapped to work in urban factories. About fifteen thousand cases of abduction are investigated each year. Although the Public Security Ministry reports an increasing number of arrests and prosecutions in cases of kidnapping and abduction, the crime wave has sapped citizens’ confidence in the local governments’ ability to maintain civil order.

Compounding all this, the decline in health care is also a very real concern. China’s rural communities once benefited from one of

the best rural health care systems in the developing world. Paramedics, known as “barefoot doctors,” were given basic training in clinical care and were the first responders in a well-articulated network of commune and county clinics and hospitals. With the economic reforms, that network frayed, and China’s rural residents today are in what one observer called medical free fall. Barefoot doctors left for the many more lucrative career opportunities open to them, and what was once a system of free medical care was transformed into a pay-as-you-go plan that is well beyond the means of most peasant households. There are wrenching tales of ill or injured peasants who are obliged to suffer because they cannot afford medical attention.

Whereas in the past the Chinese government could count on peasant acquiescence and could focus on the more volatile political behavior of workers, students, and intellectuals, today it can no longer take for granted the passivity of the peasant. As we have seen, rural China was largely inactive when students and workers in China’s cities were demonstrating against the government in 1989; rural residents were generally unsympathetic with their demands for a more open, more effective government. But since 1989, as the sources of discontent described here have taken their toll on rural toleration of incompetent governance, the climate has changed. Today there are, on average, more than 120,000 incidents of public protests involving as many as three million people each year. Most of these protests take place in the countryside; most of them involve issues of graft, land grabs, and environmental pollution. Wen Jiabao may well have been prescient in his statement on the effect of these protests on national stability.

Mao’s comment in 1930 on the volatile character of a discontented peasantry—“a single spark can start a prairie fire”—vastly understates the amount of political mobilization and organizational work that it took for the Chinese Communist Party to launch the revolution that overthrew the old order in the Chinese countryside. A thousand protests (or even 120,000 protests), if they are isolated

from one another, do not a revolution make. On the other hand, 727 million people in rural communities who harbor serious doubts about the capability of their government to address their pressing problems pose a potentially serious challenge indeed to the central authorities in Beijing.