Chapter 2

Mrs. Wiggins, the cow, was Freddy’s partner in the detective business. Some people thought it was pretty funny for a cow to be a detective, but as a matter of fact they made a splendid team. Pigs are full of ideas, but cows are full of common sense, and when you get that combination to work on a problem it’s pretty near unbeatable.

They plodded along next morning up past the duck pond and through the woods, and then across a shallow valley and up a hill, from whose top they looked down on the wide lawns of Mr. Camphor’s fine estate, spread out, smooth and green, along the blue waters of the lake. They went down through the tall iron gates and up the drive to the front door.

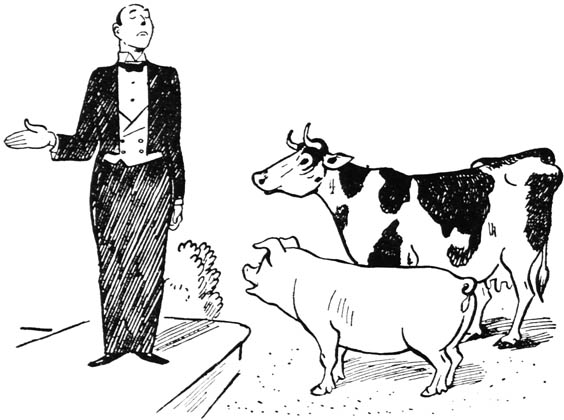

Bannister, Mr. Camphor’s butler, answered their ring. He was a tall man in a black tail coat, and he held his head so high and stiff that he couldn’t see anything in front of him except his nose, which pointed right over their heads at the tops of the trees outside.

“Hello, Bannister,” Freddy said. “Is Mr. Camphor expecting us?”

“Who shall I say wishes to see him?” inquired the butler.

“Mrs. Wiggins and Mr. Frederick Bean.”

“Kindly step in, sir and madam,” said Bannister, standing aside. “In the drawing room, please. I will announce you.” And he wheeled stiffly and marched out.

“My land!” said Mrs. Wiggins crossly. “I should think we’d known Bannister long enough so he could at least say How de do.”

“He isn’t being snooty,” said Freddy. “He’s just being a good butler. He explained it to me once. A good butler has to be dignified and formal for everybody in the house. That’s what he’s hired for—to keep everything very high class and ceremonious. That’s the advantage of having a lot of money like Mr. Camphor: if you don’t want to bother about being dignified, you can hire somebody to be dignified for you.”

Just then Mr. Camphor came hurriedly into the room. “Freddy!” he exclaimed. “My dear fellow! And Mrs. Wiggins! I’m so glad you’ve come. And not just because I need your help either. I’ve missed you animals; began to think all my old friends had deserted me.”

“There’s no friend like an old friend,” put in Bannister.

Freddy grinned, remembering how Mr. Camphor and Bannister were always arguing about proverbs, and testing them out to see whether they were really true or not.

But Mr. Camphor frowned. “I think you’ve got that one wrong, Bannister. The one you’re thinking of is ‘There’s no fool like an old fool,’ and I fail to see where that applies to anyone in this company.”

“Certainly not, sir,” said Bannister, turning pink. “Forgive me, sir; I fancy I became a bit confused in the pleasure of seeing old friends.”

“That’s real nice of you, Bannister,” said Mrs. Wiggins, “and I know you mean it. But I don’t see how you can say you’ve seen us when you’re looking over our heads all the time.”

“The lady is right,” Mr. Camphor said. “Relax, Bannister. As you say, we’re among friends. Sit down, will you?”

“Thank you, sir,” said Bannister, and sat down stiffly on the edge of a small gilt chair.

“Well, Mr. Cam—that is, Jimson,” Freddy began, “we feel rather ashamed that we seem to have come only because you sent for us.”

“If you hadn’t come when I sent for you, you’d feel ashamed, wouldn’t you? And now you say you’re ashamed because you did come. I don’t see how you can have it both ways, you’d just be ashamed whatever you did. Well, well; business before pleasure. Come meet Aunt Elmira.”

“‘Go to the ant, thou sluggard,’” Bannister quoted.

“Eh?” said Mr. Camphor sharply. “Really, Bannister, I’d prefer you to keep your opinion of my character to yourself. Just because you’re up before I am every morning …”

“I beg pardon, sir,” said the butler. “I was not referring to you as a sluggard. That is a proverb.”

“Oh, yes. Quite so. But when I mentioned my aunt, I was referring to a female relative, not an insect. So that makes us even on referring.”

“Freddy had a pet ant once,” said Mrs. Wiggins. “His name was Jerry. He could read and write.”

“Very interesting,” said Mr. Camphor. “But unless we want to get hopelessly mixed up, let’s stick to the female relatives. I want you to meet them anyway, so you’ll understand why I need your help with them.”

Miss Elmira Camphor was an enormously fat old lady who sat wrapped in shawls in a large wheel chair out on the lawn. On her head she wore a little old-fashioned bonnet like those you see in the pictures of Queen Victoria, and as they came up she peered at them through steel-bowed spectacles with an expression of deep gloom on her broad face.

“Aunt Elmira,” said Mr. Camphor, “may I present my friends, Mrs. Wiggins and Mr. Frederick Bean, the celebrated poet?”

The animals bowed, and Miss Elmira didn’t say anything.

“Aunt Elmira and Aunt Minerva are spending the summer with me,” Mr. Camphor explained. “They’ve been coming up here for the summer for—let’s see, forty years, isn’t it, Aunt? Only they’ve always stayed over at Lakeside. You see over there on the far shore—that big building among the trees? That’s Lakeside. A summer hotel. But this year, Mrs. Filmore, who runs the place, couldn’t take them. Just when she was getting ready for the summer season everything went wrong: pipes burst, porches collapsed, the help left—you never heard such a hard luck story. From what I hear, Mrs. Filmore won’t even try to open the place this year. But that, you see, was my good fortune; my aunts have come to stay with me.” He didn’t look as if he felt very fortunate.

“It’s an ill wind that blows nobody good,” put in Bannister.

“Eh?” said Mr. Camphor. He looked hard at Bannister. “Well, if you call …” he began, and then caught himself up. “Ha, to be sure, to be sure!” he said hastily. “A delightful summer for us all,” he added gloomily. “Eh, Aunt Elmira?”

Miss Elmira paid no attention to the question. She was looking at Freddy, and now her mouth opened very slowly—it was like a slow motion movie of someone speaking—and she said in a hoarse voice: “Recite!”

Freddy was puzzled. “I beg your pardon,” he said; “I don’t believe I …”

“Poem!” said Miss Elmira.

“She’d like you to recite one of your poems,” Mr. Camphor explained. “Aunt Elmira is very fond of poetry.”

“She’d like you to recite one of your poems.”

Mrs. Wiggins always said that one of the nicest things about Freddy was that when he was asked to perform—to recite one of his poems or do card tricks—he didn’t wriggle and have to be coaxed. Jinx didn’t agree with her. He said: “Coaxed! You can’t mention anything to that pig that doesn’t remind him of some poem he’s just written, and then he holds you down and reads it to you. Just a big show-off.” But of course Jinx didn’t like poetry much.

“There’s a little thing on spring I wrote the other day,” Freddy said.

“Spring is in the air;

Birds are flying north;

And though trees are bare,

Now they’re putting forth

Leaves. The fields are green.

Sun is getting higher.

Monday Mr. Bean

Put out the furnace fire.

Birds are building nests;

In the swamp are peepers;

Men discard their vests;

Eggs are getting cheaper.

All the girls and boys—”

“Stop!” said Miss Elmira.

“I—I beg your pardon?” Freddy stammered.

“Gloomy poem,” she said.

“Gloomy!” he exclaimed. “Why it’s all about spring and birds singing and …”

“Aunt Elmira doesn’t mean that your poem is gloomy,” Mr. Camphor interrupted. “She wants you to recite a gloomy one. It’s the only kind she likes.”

“Oh,” said Freddy. “Well, I don’t believe I’ve ever written a gloomy one. I’m sorry, ma’am. Maybe if I get time this afternoon I could write you one.”

“My aunt will be very pleased,” said Mr. Camphor. “Well, if you’ll excuse us, Aunt …” He led his guests up to the terrace on the west side of the house. “I suppose you’re wondering,” he said, “why I’m so anxious for your help in getting my aunts to leave.”

“Well, yes,” said Freddy. “Of course we’ve only met Miss Elmira, but I shouldn’t think she’d be much bother.”

“She isn’t. But how’d you like to have her around all summer?”

“I guess she’d make me feel kind of depressed.”

“Depressed! Ha!—just plain squashed. All day long she sits in that chair. You think of something nice to do, and then you look out the window and see her. It’s as if a black cloud came over the sun. It’s as if you had a stomach ache that you’d forgotten about, and then it starts up again. Nothing seems like fun, and the more you look at her, the more you wonder why you don’t just go up and lock yourself in your room and set fire to the house.”

“It does take the joy out of life, having her around,” Freddy said. “Maybe you could get her to do something. What’s she interested in?”

“Sorrow,” said Mr. Camphor. “Misery. Grief, woe and tribulation.”

“Well, I feel sorry for her,” said Mrs. Wiggins. “She must have had a pretty hard life, to be so gloomy all the time.”

“On the contrary,” said Mr. Camphor, “she’s had an easy one. Plenty of money, no troubles. Yet the more you try to cheer her up the gloomier she gets. Bannister and I have worn ourselves out trying to be pleasant, and telling jokes and so on.”

“And your other aunt,” said Freddy. “You said you wanted them both to leave. Is she gloomy too?”

“I’d rather you formed your own opinion,” Mr. Camphor said. “I don’t want you to think I’m just an old crab who can’t get along with his relatives. You tell me what you think after you’ve met her. In the meantime, have you—have you any ideas?” He looked hopefully from one to the other.

“Oh, yes,” said Freddy; “yes, lots of ’em. Dozens. It’s only just being sure to select the right one.” He spoke confidently, but although it was perfectly true that he had plenty of ideas, there wasn’t a single one that was any good. It wasn’t very practical, for instance, to get rid of Miss Elmira by having a giant bird, like the Roc in the Arabian Nights, fly away with her, or to tie her to a big rocket and shoot her off into space. So many of the schemes people think up for doing quite reasonable things are like that.

“Well,” said Mrs. Wiggins, “I should think the sensible thing to do would be to help that Mrs. Filmore get Lakeside open for business. Your aunts would go over there then, wouldn’t they?”

“My goodness,” said Freddy admiringly; “why couldn’t I have thought of that?”

Mrs. Wiggins laughed comfortably. “I guess you could, all right. But you’re awful smart, Freddy, and you always try to think of new ways to do things. You invent new things that I couldn’t think up in a month of Sundays. But if you want to get something done in a hurry, the quickest way is to work with what you’ve got, seems to me.”

“You’re right,” Mr. Camphor said; “only I don’t know what we can do. I’ve offered to help Mrs. Filmore with money. But she’s proud; she won’t take it, even though she’s just about broke. And anyway, she says, there’s more to it than that. The hotel is haunted. That’s why all her help left. They were scared out.”

“Haunted?” said Freddy. “Golly, I’ve always wanted to spend the night in a haunted house. Do you suppose there really are ghosts there?”

“Well, I don’t suppose so for one minute,” said the cow. “I don’t believe in ghosts. Just the same, you won’t catch me spending any nights there. I should be scairt to death.”

“I don’t see how you could be scared of something you don’t believe in,” said Mr. Camphor.

“I don’t believe in driving a car seventy miles an hour,” said Bannister, “but I’d be scared to do it.”

“Oh, shut up, Bannister,” said Mr. Camphor, “you’re trying to mix us up. Anyway, we’re not going out in the car. Unless,” he added, as a thought struck him, “we drive around and talk to Mrs. Filmore. Or wait a minute. It’s thirty miles around the lake, and only a mile across.” He looked doubtfully at Mrs. Wiggins. “I don’t suppose we could all go in the canoe?”

“We’ll all go in the lake if we try,” said the cow. “But anyway, I’m not going. That shore over there is the southern edge of the Adirondacks—nothing but woods for miles—and woods are no place for a cow. You can’t half see and you stumble over things and get twigs in your eye—and I’m not as young as I used to be. But if you two go, you ought to stay and investigate—not just talk to Mrs. Filmore. Because if you ask me, there’s something funny about this ghost business. You know, Mr. Camphor, we had some trouble with a ghost once before—that old Ignormus. But he wasn’t much of a ghost when you got to know him, and we nailed his hide to the barn door, didn’t we, Freddy?”

“Yes, I guess we ought to look into it,” said Freddy. “But my goodness, we’re detectives, not ghost busters. If we suspect somebody of something, our business is to shadow him and find out what he’s up to, and if he’s doing wrong, get the sheriff to put him in jail. But you can’t put a ghost in a jail. And how can you shadow him?”

“Set a thief to catch a thief,” said Bannister.

“Ha, you mean if you want to catch a ghost, you’d have to hire another ghost to follow him, Bannister?” said Mr. Camphor. “Not bad, not bad at all. Where can we find an unemployed ghost, Freddy? How about that Ig—Ig—”

“Ignormus,” said Freddy. “He isn’t around any more. Anyway, he wasn’t a real ghost, and I don’t believe Mrs. Filmore’s is either. But I’ll have to wear a disguise if I expect to find out anything. If there’s somebody back of this ghost, he’ll go into hiding if he sees a detective snooping around.”

“Hey, I’ve got an idea,” said Mr. Camphor. “He wouldn’t suspect campers. I’ve got a complete camping outfit—tent, sleeping bags, everything. What do you say we go camping?”

Freddy thought it wasn’t a bad idea. “But are you sure you want to go yourself? It may be dangerous.”

“Danger is the spice of life,” said Mr. Camphor, and Bannister said: “Faint heart ne’er won fair lady.”

“Don’t be silly, Bannister,” Mr. Camphor said. “I don’t want any fair lady; I want to have some fun. Anyway, we’ve got two aunts here—isn’t that enough fair ladies for one summer? Well, let’s look at the camping stuff.”