Chapter 3

The camping outfit was certainly complete. Mr. Camphor spread everything out on the living-room floor, and they selected the things they would need. There was a light-weight eight-sided tent with a center pole, rather like a tepee, just big enough for two people, which Mr. Camphor said could be set up in three minutes. There were two comfortable sleeping bags that zipped up the sides. There was a folding table and two folding chairs, and a folding water pail and a folding candle lantern, and even a frying pan with a handle that folded down so that it could be packed in a bag with the cooking pails and the cups and plates and knives and spoons.

“We’ll be camping in one place,” Mr. Camphor said, “so we can take more stuff than we could if we had to carry it on our backs. Bannister, take one of these duffel bags and fill it up with canned goods from the storeroom. And there’s a list somewhere—here it is: sugar, salt, flour; yes, fill these containers in the pantry. And we’ll take this telescope, and the …” He stopped suddenly, and Freddy looked up and saw a tall, severe looking woman with a very long sharp nose standing in the doorway.

“Jimson Camphor!” she exclaimed in a shrill voice. “Look what you’ve done to this nice clean living room! All this dirty old junk strewn all over everything; why it looks like a pigpen.”

“I’m sorry, Aunt Minerva,” said Mr. Camphor mildly, “but you see we …”

“Sorry?—sorry?” she caught him up. “What good does that do? That’s what you always say. Why don’t you think a little beforehand? Now you clean up this mess—at once, do you hear me? And see that you wash your face and hands before lunch. I never in my life …” She broke off abruptly, having caught sight of Mrs. Wiggins and Freddy, and gave a sort of screech. “Oh! Animals! Animals in the living room! Jimson, have you gone stark, staring crazy?”

“Why, these are friends of mine, Aunt Minerva,” he said, and tried to introduce them. But she wouldn’t listen. “Get them out of here!” she demanded. “Shoo!” she said to Mrs. Wiggins, making shooing motions with her hands. “Outside! Scat!”

Freddy and Mrs. Wiggins looked at each other, and the cow’s left eyelid drooped over a large brown eye. Then they started for the door.

“Animals!” Miss Minerva exclaimed disgustedly. “Animals in the house!”

“Well, what’s the matter with that?” said Mr. Camphor. He was very red in the face, but he spoke calmly. “After all, you and I are animals too, Aunt Minerva.”

“Oh, are we!” said his aunt sarcastically. “Are we indeed! And I suppose that is why you wish to turn this house into a stable. How dare you call me an animal!”

“All right, all right,” said Mr. Camphor wearily. “We’ll go out.” He picked up the sleeping bags. “Freddy, take the tent. Bannister’ll bring the rest.”

Out on the lawn they could still hear Miss Minerva scolding and complaining. Mr. Camphor looked shamefacedly at his friends. “I’m sorry,” he said. “I know I ought to have stood up for you better. After all, it is my house.”

Freddy grinned. “Not any more, it isn’t.”

“I guess you’re right, at that.” Mr. Camphor sighed. “It’s been like this ever since she got here. She drove my cook away the third day. Does the cooking herself now. But she’s not much good. Burns everything. I don’t suppose she burns everything, really. But you know how it is; after a while everything tastes burned.”

“I’m kind of burned up myself,” said Freddy.

“I know. I’m sorry about that remark she made about the pigpen …”

“Oh, forget it,” Freddy said. “I didn’t mean that. It’s for you I’m burned up. A gloomy aunt outside and a cranky aunt inside; there isn’t much peace and quiet for you anywhere. Unless you just move right out.”

“And if I did,” Mr. Camphor said, “she’d go right along with me. She says I don’t know the first thing about running a house, and it’s a blessing she came to stay when she did, because the place is going to rack and ruin the way I run it. She says it’s her duty to look after me. You see, I was an orphan, and she brought me up. I went to live with my aunts when I was five, and the trouble was, as I got older, Aunt Minerva always treated me as if I was still the same age. Now that I’m forty she still does.”

“And maybe you’ll excuse my saying so,” put in Mrs. Wiggins, “but with her, you still act as if you were five years old yourself.”

“What do you mean?” Mr. Camphor asked, and then answered his own question. “Oh, I know; she orders me around, and I obey her and don’t answer back. But after all, she’s my aunt. And then, she’s my guest, too. You have to be polite to guests.”

“Land sakes, up to a certain point you do,” said Mrs. Wiggins. “But when the guest has such bad manners that she yells at you and orders you out of your own home, she isn’t a guest any more. And doing what she tells you is all right too, when you’re five, or even when you’re twenty. But good grief, when you’re a grown-up man …” She stopped. “I’m talking too much,” she said.

“On the contrary,” said Mr. Camphor. “You’re perfectly right. I shouldn’t give in to her. But I do hate unpleasantness.”

“You get it anyway,” said the cow.

Mr. Camphor frowned. “Everything’s very difficult. Here I’ve asked you to come up and stay a few days and now I’ve got to take my invitation back. You see how she acts. I can’t even have you stay to lunch. Not that it would be any treat, everything tasting burned.”

“I still don’t see why you let her get away with it,” said Mrs. Wiggins.

“Why, because I didn’t want to get her mad.”

“But she couldn’t get mad; she was mad anyway.”

“H’m,” said Mr. Camphor, “that’s an idea. She’s mad anyway; I get the unpleasantness anyway; so why shouldn’t I do what I want to, eh?”

“She can get madder,” said Bannister.

“I doubt it. If she did, she’d just burst.”

“And what a break that would be!” said the butler.

“Come, Bannister—no slang,” said Mr. Camphor. “Well, we’ll try it. Two extra places for lunch, Bannister. Though I don’t know,” he said doubtfully; “it won’t be very pleasant for you two.”

“We won’t mind, if it’ll help you out,” Freddy said. “I suppose she doesn’t—she won’t throw things at us?”

“Frankly, I don’t know. Except for bad temper and a good deal of yelling, she’s always been a lady. I don’t think she’ll throw anything—not anything very big, anyway. But you’d better be ready to duck.”

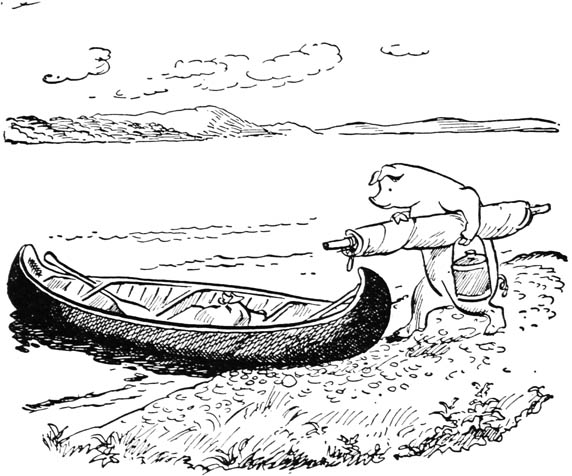

They took the camping things down and stowed them in the canoe, and then went back to the house. When Bannister announced lunch, they went into the dining room. Miss Minerva was still in the kitchen. Mrs. Wiggins was seated at Mr. Camphor’s right, and Freddy opposite her. Freddy, of course, could handle his knife, fork and spoon with ease, and even with elegance, but cows seldom acquire such skills, and indeed would find but little use for them, and so when Bannister brought in the soup plates, he put before Mrs. Wiggins a large platter of freshly cut alfalfa. Which was certainly very thoughtful of him.

He put before Mrs. Wiggins a large platter of freshly cut alfalfa.

It was then that Miss Minerva came in. She had been standing over the stove, and her glasses were a little fogged with the steam from the cooking, so that when Freddy rose politely and pulled out her chair she merely said “Thank you” rather ungraciously, and sat down and began to eat. Then as her glasses cleared she raised her eyes—and with a loud angry cry she jumped up, so violently that her chair crashed over backward on the floor. “Jimson!” she exclaimed furiously. “What are these—these creatures doing here? Now, clear them out! I spoke to you once about them and I shan’t speak to you again.”

Mr. Camphor squinched his eyes up and seemed to be trying to lift his shoulders to cover his ears, but Freddy gave him a poke under the table and whispered: “Come on; we’re right with you.” So he straightened his shoulders and looked up and said quietly: “Oh, I think you will, Aunt.”

“What’s that?” she snapped. “Such impertinence! How dare you speak to me like that? Bringing these disgusting animals to the lunch table, and then saying you think I will!”

“Will what, Aunt Minerva?” he asked.

“Will—will …” She got mixed up and sputtered for a minute like a pinwheel, going round and round and throwing off sparks, but not getting anywhere in particular. Then as Freddy and Mr. Camphor continued to eat their soup, and Mrs. Wiggins to munch her alfalfa, she drew a deep breath and said: “Very well! Very well! If you choose to bring the farmyard into your dining room, I wash my hands of you. I’ve never eaten with pigs, and I’m not going to begin at my age.”

“Better late than never, eh, Bannister?” said Mr. Camphor, and giggled faintly into his soup spoon.

“As you say, sir,” the butler replied. “There’s no time like the present.”

Miss Minerva turned and stamped out of the room. But before Freddy could congratulate his host on his success, she came back and sat down determinedly in her chair. “I’m not going to be driven out of my own home by a parcel of animals, even if you haven’t the decency to drive them out,” she said. Then she turned to Mrs. Wiggins. “I should think you’d be ashamed to force yourself in here where you’re not wanted,” she said.

“Well, ma’am,” said the cow, “if that’s what you think, that’s what you think,” and went on eating.

Miss Minerva started on her soup. She didn’t say anything more for a while, but kept glancing with distaste at Freddy, and then putting her handkerchief to her nose and turning away. And at last this made Mr. Camphor angry. He could stand her picking on him, but he wasn’t going to have her picking on his friends. He said: “Does the soup smell burned to you, Aunt?”

“The soup is excellent,” she snapped, “and much too good for the company.” And she glanced at Freddy and put her handkerchief up again.

Mr. Camphor drew himself up. Although he hired Bannister to be dignified for him, he could be pretty dignified himself when he had to. “Then if you can’t be polite to my guests,” he said, “you had better leave the table.”

She dropped her spoon and looked at him as if she couldn’t believe her ears. “You are telling me to leave the table!” she exclaimed. “How dare you, Jimson Camphor!” She glared at him, but he returned the look sternly, and in a minute she dropped her eyes. She picked up her soup spoon and said in a quieter voice: “That I should live to see the day when you would insult me like this! This I can never forgive.” Then, as he didn’t say any more, she went on eating. But she didn’t put her handkerchief to her nose again.

After a time Freddy said: “Very good soup, Jimson. Delicious.”

It was really terrible soup, and badly burned into the bargain. Mr. Camphor said shortly: “H’mp, glad you like it.” But Miss Minerva turned and looked for the first time full at Freddy. “The first word of praise for my cooking that I’ve ever heard in this house,” she said; “and it had to come from a pig!” But nobody answered her, and for the rest of the meal she was silent.

Bannister took out the soup plates and brought in an omelet—which was scorched—and, for Mrs. Wiggins, a big bowl of hay, with a side dish of oats. The dessert, an Indian pudding, was also burned, but the sauce was good, and they ate that. Mrs. Wiggins, however, ate her pudding and all of Freddy’s. She smacked her lips rather too loud over it, but Miss Minerva didn’t seem to be offended, and even gave her a vinegary smile.

After lunch, when Miss Minerva had gone back to the kitchen, they sat for a while on the terrace.

“You know, Freddy,” Mr. Camphor said, “this is the first meal I’ve sat through with Aunt Minerva that she hasn’t scolded me from the time she unfolded her napkin to the time she pushed back her chair. I believe maybe you and Mrs. Wiggins have shown me how to get along with her.”

“You mean praising the food?” Freddy asked.

“No, I mean going ahead and doing what I want to in my own house.”

“Well, good land, it wouldn’t hurt you to pay her a little compliment now and then,” said the cow. “If you praised her cooking she might improve it.”

“Maybe. But even if she did, she’d still object to everything I do. Anyway, I couldn’t. If I’d tried to compliment her on that awful soup, the words would have stuck halfway out. How you ever ate that pudding, Mrs. Wiggins …”

“I liked it.”

“Well, there’s no accounting for tastes,” said Mr. Camphor, and Bannister, who was taking a luncheon tray down to Miss Elmira, said: “The proof of the pudding is in the eating.”

“Who wants to eat the terrible stuff?” said Mr. Camphor. “No, you see,” he went on, “I’ve always done what she wanted me to, even the silliest things, just to save trouble. But it didn’t save anything—I got yelled at just the same. Yes, after this I’m going to …”

“Jimson!” came Miss Minerva’s voice from the kitchen window. “Don’t sit out on that damp terrace without your rubbers. Go get them on at once!”

Mr. Camphor got up. “Yes, Aunt Minerva …” He stopped short. Freddy and Mrs. Wiggins were frowning ferociously at him. He sat down again.

“Hurry up, Jimson,” Miss Minerva shouted. “I’m not going to nurse you through another of your colds.”

Mr. Camphor waved a hand airily at her, then turned away and began talking to the animals. Miss Minerva glared for a minute, then slammed the window down hard.