Chapter 5

Freddy and Mr. Camphor stumbled along the trail by the light of their candle lantern, and pretty soon through the trees they saw a faint yellow glow. Then they came out in a clearing, and beyond them was the dark bulk of the hotel, with a light in one of the downstairs windows. Something moved on the porch, and a woman’s voice said: “Stop right where you are!”

“It’s me, Mrs. Filmore,” said Mr. Camphor. “We’re camping down by the point, and we thought we heard a shot.”

“You did. Come in and I’ll tell you about it.”

They went up on the porch and followed her through the darkened lounge into a small office, lit by a kerosene lamp. She was a tall nice-looking woman with a worried expression on her face and a pistol in her hand. She put the pistol in a desk drawer, but she kept the worried expression on, and said: “I’m glad to see somebody human, though—” she smiled—“you do smell dreadfully of mothballs. There are things going on here … well, I’ve never been much of a believer in ghosts, but it’s got so now, with the rapping and groaning and footsteps in empty rooms and wild Indians peering in through windows that nobody can get a wink of sleep all night.”

“Let me present my friend, Dr. Hopper,” said Mr. Camphor. “He’s rather an authority on ghosts; perhaps he can help you.”

“Too late for that,” said Mrs. Filmore. “I’ve given up. I’m leaving tonight.” She pointed to several suitcases which stood by the door.

“I’m sorry to hear that,” Mr. Camphor said.

“I’m going to drive to Centerboro, going to stay with my cousin, Mrs. Lafayette Bingle for a while. Until I can find a job.”

“I know Mrs. Bingle,” said Freddy, forgetting for a moment that he was Dr. Hopper. “Please remember me to her. I—I attended her professionally.”

This was quite true, but it had been as a detective in a matter of lost spectacles, not as a doctor.

“If your going is a question of money,” Mr. Camphor began.

She shook her head. “You’re very kind. It’s true of course, I have no more money to pay workmen. But even if I felt that I could accept a loan, I doubt if all the money in the world could get this place in shape to open. As soon as one thing is fixed another breaks down. And my help has all left. No, I shall have to sell for what I can get. There!” she said, as there came a series of loud knocks from somewhere upstairs. “How long do you think a waitress or a handy man would stay with that kind of thing going on? And if the help stayed, how would my guests like it? No,” she said as Mr. Camphor reached for his lantern, “there’s no use going to look; there won’t be anybody there.”

“Well, ma’am,” said Freddy, “don’t you think somebody real is behind all this? I mean, some enemy? Who could come up every night and put on a ghost show?”

“How would they come?” she asked. “How could they get here—in a car, a motor boat-without my hearing them?” She looked at him curiously, her eyes disapproving of the coon-skin cap, which of course he had had to keep on to avoid being recognized as a pig.

“I hope you’ll excuse my wearing my cap,” he said. “You see, I …” Then he stopped. He couldn’t think of any reason why Dr. Hopper couldn’t take the cap off.

But Mrs. Filmore was too upset to care. “I’ve given up guessing what it’s all about,” she said. She pointed to the window, in which there was a small round hole. “That was the shot you heard. There was a face, and I fired at it. I couldn’t have missed. But when I went outside there was nothing there.” She got up. “You’ll excuse me, but it’s getting late and I must go.”

They helped her carry the bags out to the car. As they watched the red tail-light bobbing and jigging over the rough narrow track that followed the shore three miles out to the state road, Mr. Camphor sighed. “I don’t know what the poor woman’s going to live on. Every cent she had was in this hotel. A haunted hotel! My goodness, what could you do with that?”

“I bet she could get a lot of people to come and stay,” said Freddy. “People who want to show off how brave they are.”

“Not if she couldn’t get cooks and waitresses to stay. I guess I’m brave enough to meet a ghost, but I’m not brave enough to stay at a hotel where they don’t serve meals.”

“No, I guess I’m not either. You know what Napoleon said: an army travels on its stomach.”

“On its stomach!” Mr. Camphor exclaimed. “Ha, I’d like to see an army do that. It couldn’t make a mile a day.”

“I think he meant that an army can’t be brave unless it has plenty to eat,” Freddy said.

“Well, why didn’t he say so then? That’s a pretty roundabout way of saying something that everybody knows anyway.” He turned quickly to Freddy. “Look,” he said, “we’ve had plenty to eat. We’re so full of flapjacks that our arms and legs stick right out straight like those little rubber balloon men that you blow up. We ought to be brave enough to tackle a haunted house. What do you say we spend the night here? Maybe we could find out something about this ghost, eh?”

“Why, sure, sure,” Freddy said. “Only—well, had we ought to leave all our stuff unprotected?”

“Who’s going to run off with it—the squirrels and the chipmunks?”

“No, but we’re supposed to be camping—roughing it, sort of. Isn’t it kind of sissy to spend the very first night you’re out camping in a hotel?”

“H’m,” said Mr. Camphor, “well now you mention it I guess you’re right. Anyway, we can see better to explore the place by daylight.” He turned to lead the way back along the trail, and then swung round suddenly. “No!” he said determinedly. “We’re just kidding ourselves. We’re afraid—we’re scared of all those empty rooms, and the darkness and the noises. Well anyway, I am.”

Freddy glanced at the black bulk of the hotel and thought of those heavy knocks, and of faces looking in the windows—ferocious Indian faces—and shivered. “Oh, dear,” he said; “I remember saying to somebody, or was it somebody said it to me?—anyway it was when that Ignormus had us all so scared, and I said, or somebody said, if you were scared of something you ought to walk right up to it and say Boo! And then you’d find there wasn’t anything to be scared of at all.” He shivered again. “It—it seemed a good idea at the time.”

“I don’t think saying Boo is such a good idea,” Mr. Camphor said. “I mean, what would it get you? I mean, a ghost—wouldn’t he think you were kind of silly if you just stood there and said Boo?—Oh, come on, Fred—I mean, Doctor. We’re going to feel pretty cheap tomorrow morning if we just go back to the camp now.”

So Freddy said unhappily: “All right,” and they went back into the hotel. In the office they relit the oil lamp, then brought two long cushioned wicker settees in from the lounge, and, turning the light down a little, had just settled comfortably on them when …

Tap, tap, tap, tap. Somebody was rapping on the window.

Freddy shut his eyes tight and pretended not to hear anything.

Tap, tap, tap! Slower and louder. Freddy felt a procession of ants with very cold feet walking up his backbone.

“D—did you hear something?” Mr. Camphor whispered.

Freddy gave a gentle snore.

“Oh, come on,” said Mr. Camphor. “You can’t be asleep yet. Look, you’re facing that window—I can’t see it without turning around, and I—I might scare ’em. Just take a peek, will you?”

But Freddy wasn’t taking any peeks. He didn’t see how he could be any more scared than he was, but he knew if he saw what was at the window he would be. He squeezed his eyelids so tight together that he saw stars and pinwheels.

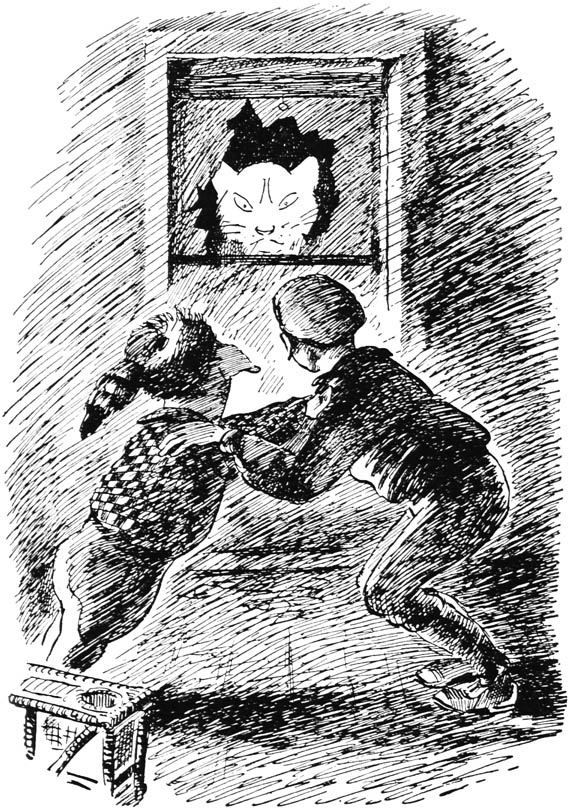

Rap, rap, crash! Something had smashed the window, and as the bits of glass tinkled on the floor, Freddy and Mr. Camphor jumped up and grabbed each other. Looking through the jagged hole in the glass was the head of a huge cat. It was as big as a man’s head and it had fierce whiskers. It stared ferociously at them and then dropped out of sight.

It was as big as a man’s head and it had fierce whiskers.

They hung on to each other for a minute, then Mr. Camphor let go and ran over and pulled down the windowshade while Freddy turned up the lamp.

Mr. Camphor’s teeth still chattered a little as he said reproachfully: “You hadn’t ought to have tried to get behind me, Freddy.”

“Get behind you!” Freddy exclaimed. “It was you that was trying to get behind me!”

“Oh, well,” said Mr. Camphor, “I guess we were both trying to get behind each other. And that would be kind of hard, wouldn’t it? We might try it again sometime when we aren’t busy. I guess …” He stopped short and grabbed Freddy’s shoulder. “Look!” For the door into the darkened lounge, which they had pulled shut, was opening very, very slowly.

And as it opened they backed, just as slowly, away from it. They backed, without thinking of it, right up against the window. And when their shoulders touched the drawn shade, from outside, almost in their ears, came a long wailing screech.

That finished them. They both jumped a foot in the air, and when they came down they were running. They jammed together for a moment in the doorway, and the next thing they knew, they were half way down the trail to Stony Point. They only stopped then because Mr. Camphor tripped over a root and fell, and Freddy stumbled over him.

They lay panting where they had fallen. “Lucky—didn’t break our necks,” Mr. Camphor wheezed. For they had of course left their lantern in the hotel, and though the night was clear, there was no moon, and the starshine was too faint to be of any use to eyes that had just left a lighted room.

Gradually their eyes became accustomed to the darkness and they got up and went on. Their campfire had burned down, but the embers still glowed, and when they threw on fresh wood the flames leaped up and the light flickered on the green leaves and brown tree trunks that surrounded them, on the bottom of the overturned canoe and on the …“Where on earth is the tent?” Freddy said suddenly.

They ran over to it. It was there, but it was a complete wreck. The loops by which it was pegged to the ground were cut so that the center pole had fallen over, there were long slits in the canvas, and all their supplies were scattered about outside. Everything that could be torn was torn, and everything that could be spilt was spilt.

“The canoe, Freddy!” Mr. Camphor exclaimed, and they hurried down to the beach. But the canoe hadn’t been touched.

“You know, that’s funny,” he said. “They smashed everything else; why leave the canoe?”

“Maybe it’s kind of a hint that they want us to get in it and go,” said Freddy.

“Maybe so. But smashing our stuff would be hint enough, wouldn’t it? My goodness, I’m glad they just hinted and didn’t say right out what they meant.” He went back and began poking around in the wreckage. “Well, here’s the frying pan and the pail. The canned stuff is all right. And we’ve got a hatchet. Why Freddy, with these and our sleeping bags we’ve still got a camping outfit. You know, maybe I’m the kind of person that can’t take a hint, because I don’t think I’m going back home—I’m going right on with this camping trip. We’ll paddle across tomorrow and get some guns, so if these people give us any more hints, we can hint right back at them. How about it?”

Freddy said: “It wasn’t any ghost that wrecked the camp, and I want to look it over by daylight. Maybe there’ll be some clues. Sure, I’ll stick. But where will we sleep?”

“In the sleeping bags. They’re not entirely ruined. And I guess it will be a pretty tough mosquito that’ll try to get through this smell of mothballs to bite us.

“But it might rain. We’d better build a lean-to shelter. Let’s see, we want about three ten-foot poles and some shorter ones. We can roof it with what’s left of the tent. Let’s have the hatchet.”