Chapter 8

When they left the Macy pond, Freddy and Jinx separated. The cat went back to the farm to tell the animals about Mr. Eha, and Freddy went on down to Centerboro, and called on Mrs. Lafayette Bingle, with whom Mrs. Filmore had gone to stay. Mrs. Bingle welcomed him warmly; he had once done a small detective job for her and she had been very grateful.

“Come in,” she said. “This is an unexpected pleasure. What can I do for you?” He asked for Mrs. Filmore. “My cousin is out,” she said, “but she’ll be back in a few minutes.”

“Well,” said Freddy, “Mr. Camphor and I have discovered some things that she ought to know.” And he told his story.

“Dear me,” said Mrs. Bingle, “this is indeed terrible! Mr. Eha, you say? An odd name—is it Turkish? Not that it matters; we’ll find out who he is when he buys the hotel.”

“Yes,” said Freddy, “but then it will be too late.”

Mrs. Bingle looked doubtful. “Mrs. Filmore has used up her last cent, and she owes a good deal of money. She has got to sell. And in fact she has gone downtown this morning to see about it.”

“Oh, dear,” said Freddy; “we must get her to hold off. She …”

At that moment the door opened and Mrs. Filmore came in. She seemed surprised to find a pig in the parlor, but when the whole thing had been explained to her she smiled rather sadly and said: “So you really did attend Mrs. Bingle professionally, though as a detective and not as a doctor. I told her about Dr. Hopper, but she said she’d never heard of him, and we’ve been wondering who on earth he was.”

“It’s odd we didn’t think of Freddy,” said Mrs. Bingle. “He has so many disguises that when Centerboro people see some stranger in town, they always wonder first if it isn’t our detective, working on a case. Anyhow, we know he isn’t this Mr. Eha.”

“I’ve never heard the name,” said Mrs. Filmore. “Not that it matters; I’ve got to sell soon, and even if you found out who he is, what could we do? Have him arrested? We couldn’t prove anything.”

“No, but there are other things we could do.”

Mrs. Filmore shook her head. “If I get any kind of an offer I shall have to take it. As a matter of fact, when I stopped in to see Mr. Anderson, the real estate agent, he said that he had an inquiry only yesterday for a hotel property like mine. He’s going to talk to this person, and then let me know.”

“Who is the inquiry from?” Freddy asked.

“He wouldn’t say. He said he was not at liberty to disclose the man’s name.”

“That sounds queer.”

“Oh, I don’t think so,” said Mrs. Filmore. “Mr. Anderson said the person didn’t want to appear in it at all. He wants Anderson to buy it and make all the arrangements. Then he’ll hire a manager to open the hotel and run it. People often buy property that way.”

Freddy didn’t say any more, but when he left he went into the drugstore and looked in the telephone book. He looked for Anderson.

Anderson, A.G., 109 Elm |

1335 |

Anderson, Mrs. Dimple, 17 Cranberry |

2488 |

Anderson, Dougal, lawyer, 76 Main |

3003 |

Anderson, Edw. Henry, rl. est., 45 Clinton |

2949 |

“That’s him,” said Freddy, and rang the number.

“Mr. Anderson,” he said when he had the man on the phone, “this is Horace Green, formerly proprietor of the Ocean House at Wophasset, Mass. I’m looking for a small summer hotel in this locality—want to buy it and open up this coming season. Do you know anything of the kind within, say, fifty miles?”

Mr. Anderson’s hearty voice hurt Freddy’s ear. “Hotel, eh? Sorry, Mr. Green. I’d like your business. But I don’t know of a thing—not a blessed thing, and that’s a fact.”

Freddy asked a few more questions, but got nowhere, and then hung up. “Funny,” he thought. “If Mrs. Filmore wants him to sell Lakeside, why wouldn’t he tell me about it? I don’t get it.”

Freddy made a few more short calls in Centerboro and then got a bite to eat at Dixon’s Diner, so that it was almost dark when he finally got back to Mr. Camphor’s. The breeze had gone down with the sun and the lake was like glass as Bannister started to paddle him across the lake.

“I don’t see how you keep the canoe going straight when you just paddle on one side,” Freddy said.

“One can do several things to keep it straight, sir,” said the butler. “The twist at the end of the stroke swings it back to the side you’re paddling on. Scooping your stroke under the canoe will turn it to that side, and so will taking the stroke with the inside edge of the paddle twisted a little towards you.”

“But you paddle so silently. I thought to do that you had to bring back the blade for the next stroke under water.”

“You can do that,” Bannister said. “But if you put the paddle in and take it out quietly, and then when you bring it back for the next stroke, hold the blade a little up, so the water runs up the shaft instead of dripping off—see? On a still night like tonight, those drops make a lot of noise.” He shook a few from the paddle and they tinkled.

Freddy didn’t say any more. We’re gliding, he thought—gliding like a ghost. Through space, with empty sky above and below us. You can’t even tell which is up and which down, for you can’t see the water. There are only stars, above and below the boat.

From somewhere across the lake came a faint hollow thump or knock, and at once Bannister stopped paddling. “Did you hear that?” he said in a low voice. “Someone hit a paddle against the gunwale of a boat.”

They listened, but it didn’t come again, and Bannister went on, but more slowly. “Why only once?” he said. “If it’s someone rowing or paddling carelessly, you’d hear it again.”

“Well, what of it?” said Freddy. “Lots of people must use this lake.”

“Summer people,” Bannister said. “But it’s too early for them. There’s nobody at the Boy Scout camp down at the outlet. If it was an hour or two earlier, it might be somebody trying to get a look at a deer. I don’t say it’s any of our business, but under the circumstances, let’s get in under the shore where they won’t have us against the starlit water.” He paddled on, swiftly and noiselessly.

Halfway between Jones’s Bay and Lakeside they slid in under the loom of the trees that overhung the water and sat silently waiting. A very faint red glow came from somewhere near Stony Point.

“Mr. Camphor hasn’t got a very big fire,” Freddy whispered.

“Better not whisper, sir,” said Bannister. “A whisper carries farther on a still night than if you just speak low.—Ha! Look out there—down the lake a little!”

At first Freddy couldn’t see anything but the reflection of the starlit sky in the water. Then at one spot the stars quivered and shook. Something had disturbed the smooth lake surface. And then a patch of darkness, blotting out the starshine, moved across the water. It glided in towards the Lakeside dock.

They saw a flashlight flicker; someone was walking up the dock towards the hotel. “We’d better get Mr. Camphor,” Freddy murmured, and Bannister’s paddle slid into the water. The canoe swung round and moved back towards Stony Point.

Mr. Camphor walked down to meet them as they beached the canoe. “My goodness, you’re late,” he said. “But Bannister, why did you come over? How are you going to get back?”

“Not so loud!” said Freddy. “Our friend is up at the hotel. Look, I want to do a little sleuthing.” He took off the coonskin cap and handed it to the butler. “You be Dr. Hopper for a while. Sit by the fire with Mr. Camphor, but not so close that anybody can see you very well. I’ll be back.” And he sneaked off up the path to Lakeside.

He crept around to the back of the hotel and crouched under the office window. There was no light inside. The shade was still pulled down, but through the broken pane he could hear a voice speaking in a sharp whisper. “I don’t intend to tell you where Ezra is, my friend. He’s locked up in a safe place. Nothing will happen to him if you obey my orders.”

“Oh now, Mr. Eha, sir,” said an oily voice which Freddy recognized as that of his old enemy Simon; “it isn’t that we don’t trust you; it’s that you don’t trust us. We rats are for you a hundred per cent. We’ve done everything you’ve asked us to …”

“I don’t trust anybody,” the whisperer interrupted. “As long as you obey my orders, I’ll supply you with food—better food, I may point out, than you’ve ever had before in your lives. And Ezra will be well treated. But if you fail to carry out orders—well, you know what will happen to him.”

“But why are you suspicious of us?” Simon whined. “We have been loyal …”

“I don’t expect loyalty; I expect obedience. This is a business arrangement. Each of us has agreed to do certain things. And I intend that you shall carry out your side of the bargain.

“But that’s enough about that,” he said. “Our job here is about done. Mrs. Filmore has been driven away. A day or two more and the hotel will belong to me. Tonight I will take you back to your cottage. Tomorrow night we go to Camphor’s. We’ll start on that place at once. There’s nobody there but old Camphor, his butler, and the two old maid aunts. We’ll proceed in the same way—do enough damage to make the house unlivable, and scare ’em out with the usual ghost stuff. It should take about six weeks. Then we’ll move on to the Bean farm.”

“Ha! The Bean farm!” Simon snarled. “Ever since that fat-faced Freddy and his friends drove us off the place I’ve been waiting to get even. I swore I’d come back some day and live in that barn.”

“You do what you’re told and you’ll get the barn,” said Mr. Eha. “I’ve promised you that. But we’re wasting time. I’ve got to get rid of this camping party. They’re too much interested in what’s been going on at the hotel.”

“If you take my advice you’ll shoot ’em,” said Simon. “They’d be easy to pick off, sitting around their fire.”

“Your advice is stupid,” the other whispered. “A shooting would bring the state troopers up here. They’d talk to Mrs. Filmore, and policemen don’t believe in ghosts, particularly ghosts that shoot off guns. Now you get the rest of your gang and go on down to the dock and wait for me.”

“You going to leave those things here?” said Simon. “Suppose Camphor comes in here and finds them?”

“After the scare I gave him last night?” said Mr. Eha. “He wouldn’t come into this room again after dark for a thousand dollars. Get along.”

Freddy left the window and crept around the far side of the hotel until he reached a corner from which he could see both the front door and the shore end of the dock. Pretty soon there was a scrabbling and scampering on the porch, and he could just make out the dark forms of the rats as they came out of the door and hurried down to Mr. Eha’s canoe. He thought there were about twenty of them. A minute later a figure appeared in the doorway. Even though Freddy knew what it was, it was pretty terrifying. It was draped in something white that fluttered in a very ghostly manner. But the head was the worst. It was the head of some kind of demon, with great round eyes and long tusks, and it glowed with a sort of smoky luminosity.

Freddy shuddered in spite of himself. “Luminous paint, I suppose,” he thought. “Golly, wait till Mr. Camphor and Bannister see that goggling at them! They’ll just give one squawk and fall right over on their faces.” He giggled nervously. “Boy, I’d like to see ’em!”

But when the figure moved on down the path toward the camp, he went up the steps and into the house. For if Mr. Eha had left something in the office, now was his chance to see what it was.

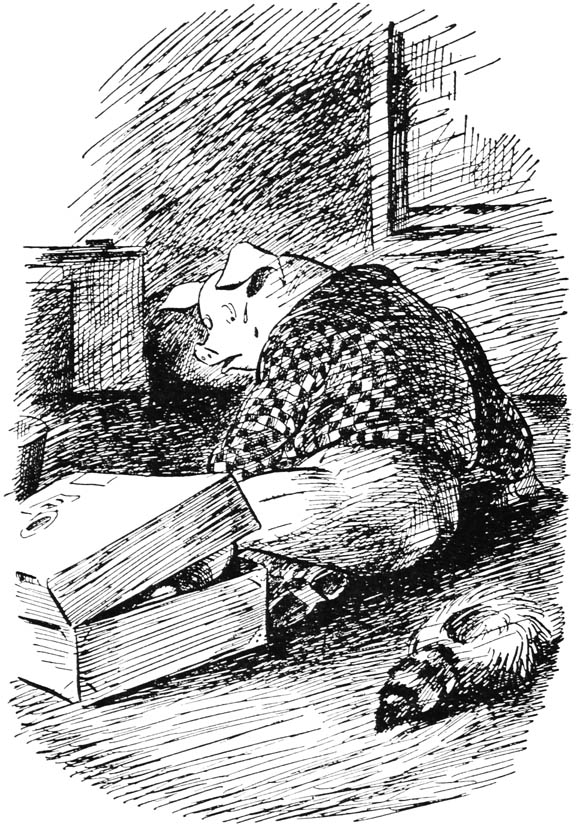

Of course he couldn’t see a thing. The office was pitch black, and it wasn’t much fun feeling around in the darkness from which that horrifying figure had come. As a banker, Freddy didn’t take much stock in ghosts, but as a poet, he had a lively imagination, and he began to think of all the things that he might find: of fingers that might tap him confidentially on the shoulder, of cold hands that might clasp his wrist, of thick, oily groans that might come from that far corner. Then he fell over something and gave a groan himself, for there was a thump, and jaws snapped shut on his leg.

Freddy was good and scared. He thought of steel traps. He thought of alligators. He lay there for a moment and cold perspiration ran down his back under the heavy wool shirt. But the jaws didn’t do anything, and they weren’t very tight. He drew his leg out cautiously, and then felt around on the floor. A suitcase! It had been open when he fell over it, and the lid had come down and caught him.

Freddy was good and scared.

Freddy felt foolish, and you can’t feel foolish and afraid at the same time. He got up and went through the suitcase, feeling of every article. There were some pieces of cloth, and a small bottle, and several things that he couldn’t identify. There were two false faces, and remembering the advice he had once given some one—or someone had once given him—to walk right up to a ghost and say Boo! he took one of them out and put it on. On the back of a chair was a coat—it was certainly Mr. Eha’s, but the pockets were empty except for a few slips of paper, which Freddy took. He didn’t have any matches, so he couldn’t see what they were. He felt of the coat, but the cloth was—well, just cloth. There was nothing he could recognize it by if he saw it again. And yet, wasn’t there something he could do, he wondered, so that if he ever did see it again, he would know that the wearer was Mr. Eha?

“Oh, dear,” he thought, “if I only had a knife I could make a little cut somewhere, maybe on the back where he wouldn’t notice it. Then if we just watched for that coat …” He felt in all his pockets. Some string. Half a candy bar. And what was this in the upper shirt pocket? “Good gracious,” he said, “three mothballs! No wonder this shirt never gets the smell aired out of it.” And he was just about to throw them away when he had an idea, and he slipped the mothballs into the outside breast pocket of Mr. Eha’s coat.