Chapter 10

At the first pale glimmer of dawn Freddy crawled out of his sleeping bag. Mr. Camphor, in the other bag, and Bannister, rolled up in a blanket, seemed to be having a snoring competition. Freddy listened a minute and awarded the prize to Bannister—his snores weren’t as loud, but they had more variety. Then he went down and washed in the lake.

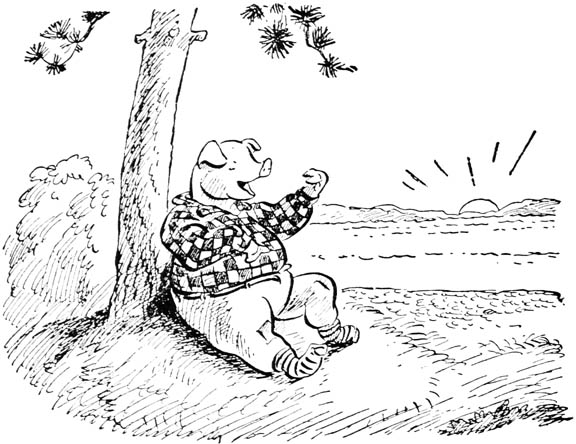

The light was growing, and the eastern sky began to glow red, as if some giant had opened a furnace door behind the hills. Freddy sat down and watched it and sniffed the fresh morning smells of water and pine and spruce and damp earth, and he thought: “My goodness, I didn’t know camping was so nice. But am I hungry! Don’t suppose I ought to start the fire till they get up though. Maybe I won’t be so hungry if I make up a poem.”

So he started one. It went to the tune of Mandalay. He sang it:

By the old hotel at Lakeside, looking southward ’cross the sea,

There’s a bright campfire a’burning, and I know it burns for me.

For the wind is in the pine trees, and the murmuring needles say:

Come you back, you pig detective—come you back to Jones’s Bay;

Come you baaaack to Jones’s Ba-a-a-ay!

Then he went on with the chorus, a little louder. And gradually—as sometimes happens to poets—his hunger for breakfast got mixed up in the poem, so that the chorus went like this:

Oh, the road to Jones’s Bay! Where the flying flapjacks play!

You can hear the bacon sizzling from your bed at break of day.

On the road to Jones’s Ba-hay, we will sing and shout hooray;

A-and when your breakfast’s ready, they will bring it o-on a tray!

“Well, well,” he said, “I guess I’d better do something to take my mind off my stomach.” There was a cold flapjack left over from last night lying on a plate beside the fireplace. He picked it up and took a bite out of it, but even the sharpest appetite will blunt itself on a cold flapjack. He started to throw it in the lake, then put it in the frying pan and practiced flipping it. He thought he would practice until he could make it turn three complete somersaults without missing the pan when it came down, and would then astonish Mr. Camphor with his skill.

But after ten minutes he had dropped the flapjack so many times that it was about worn out. And the snoring competition in the lean-to was still going on. He thought: “My gracious, I’m neglecting my detective duties. They won’t wake up for another hour. I’d better go up and snoop around the hotel.” So he did.

It wasn’t very good snooping. The office and the lounge offered no clues. It wasn’t until he started down the dock that he found the handkerchief. An ordinary white handkerchief with EHA marked on one corner in indelible ink. “So Eha is really his name,” he thought. “But what does that get me? I still don’t know where he lives.” And he was thinking this over when a little squeaky voice said somewhere: “Help!”

Freddy looked all around but couldn’t see anybody. “Where are you?” he called.

“In the boathouse.”

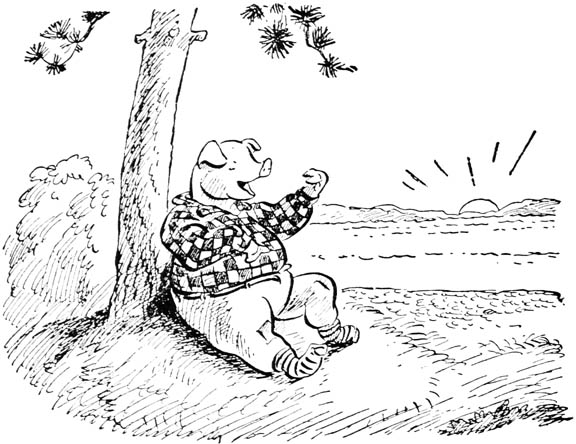

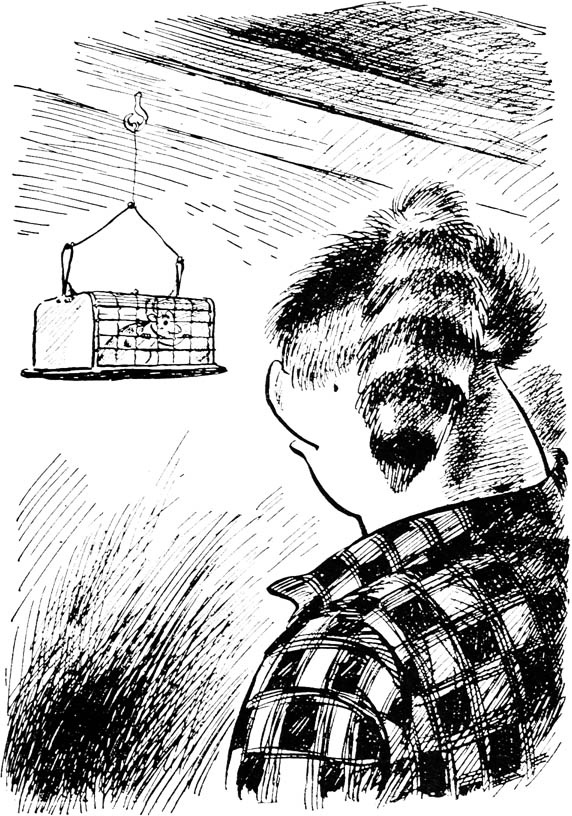

There were a number of canoes and row-boats on racks in the boathouse. Back of them, and hung from a hook in the ceiling was a big rat trap—a square wire cage with a spring door. In it was a rat.

Rats look a good deal alike,—and so for that matter do squirrels and pigs and elephants. But when you get to know them, you find that they differ in looks as much as people do. Freddy had known Simon and his family pretty well, and he recognized this rat at once as Simon’s son, Ezra, the one that Mr. Eha was holding as hostage for his family’s good behavior.

As soon as he saw Freddy, Ezra sat up and put his forepaws against the wire and began begging to be let out.

Ezra put his forepaws against the wire and began begging to be let out.

“Now wait a minute,” said Freddy, realizing that the rat hadn’t recognized him, “if Mrs. Filmore caught you in this trap, I can’t let you out without her permission.”

“Mrs. Filmore didn’t have anything to do with it,” Ezra squeaked. “Who are you, anyway? I never saw you before.”

“Well, I know who you are,” said Freddy. “If I’m not mistaken, you’re closely related to a rat that lived in my barn all one winter. Old Simon. Fine, sturdy old fellow, Simon; we got to be great pals. You look enough like him to be his son.”

“I am his son. And if you let me out—I tell you he’s offered a big reward for me and you’ll get it all,” he said eagerly. “Look, you tell me where you live and he’ll bring it to you. Tomorrow.”

“H’m,” said Freddy, “you’re a better liar than I am, Ezra.” He took off his cap. “Know me now?”

“Oh, gosh!” said Ezra. “Freddy! Oh, gee, I’m sunk now all right.” And he lay down on the floor of the cage.

“Maybe so,” said the pig, and he picked up the trap and started down the trail to camp. “If you tell me what we want to know, maybe we’ll let you go.”

The two men were up and getting breakfast. They didn’t think much of Freddy’s capture. “He’s just one of the gang,” said Mr. Camphor. “Now if you’d captured them all.… Sit down and have some coffee.”

“He’s Simon’s son,” said Freddy. “My guess is that in the hurry of getting away last night they forgot all about him down in the boat-house. But Mr. Eha doesn’t want to lose him, because Ezra is the only hold he has over Simon, and he needs Simon’s help for his scheme. I bet you anything he comes back for Ezra tonight.”

“And then what do we do?” said Mr. Camphor. “Chase him around in the woods and make faces at each other again?”

“The trouble is,” Freddy said, “that we don’t know who Eha is. Maybe Simon knows, but I don’t believe that the other rats do. I don’t think Ezra knows anything. Eh, Ez?” he said, glancing at the cage.

The rat made a face at him.

“But I’m pretty sure he lives in Centerboro,” Freddy went on, “because—look at these.” And he drew out the slips of paper he had found in Eha’s coat. They were checks for meals that someone had eaten at Dixon’s Diner. “He must eat at the diner often,” Freddy said, “because he wouldn’t be able to sneak every check he got into his pocket and walk out without paying, which is what he must have done. For how else could he have got them? You know what?—I’m going down to Centerboro and try to find him this afternoon.”

“Well, even if you did find out who he was,” said Mr. Camphor, “the police wouldn’t believe any such story. Rats and ghosts! They’d just give you the old heave-ho.”

“Sure. We won’t bother the police. We’ll just bother Mr. Eha. You leave it to the old reliable firm—they know how to handle crooks.—Hey!” he said suddenly. “What goes on?” And he pointed across the lake.

Far across where the lawns of the Camphor estate made a pale green line on the distant shore, something white fluttered.

“Someone waving a tablecloth,” said Bannister.

“Must be something wrong,” said Mr. Camphor, getting up. “Better go see.”

Freddy sat in the middle of the canoe with the rat trap on his knees, and under the strong strokes of Mr. Camphor and the butler the canoe cut sharply through the blue and silver ripples. As they came closer the lawns widened out, the house and the dock and the trees grew larger, and a group at the edge of the water grew more distinct. “Ha!” Freddy exclaimed. “Reinforcements!” And there indeed were nearly all the animals from the Bean farm—Mrs. Wiggins and one of her sisters, Mrs. Wogus, Charles and Henrietta, Robert and Georgie, the dogs, Jinx, and even the four mice: Eek and Quik and Eeeny and Cousin Augustus. “And my gracious!” said Freddy. “There’s Mr. Bean too!”

It was indeed Mr. Bean who stepped forward and held the canoe for them as they climbed out.

“Very pleased to see you, sir,” said Mr. Camphor, shaking hands with him. “I take it you’ve heard about the plans this villain Eha has for getting hold of our property, and have brought these animals up to defeat him.”

“’Tain’t my doing,” said Mr. Bean. “Mrs. Bean, she heard about it somewheres.” He frowned slightly. He was kind of old-fashioned about having animals talk; it made him uneasy, and he always said animals should be seen and not heard. So Freddy and his friends seldom said anything to him; if there was anything important they told Mrs. Bean. He never asked her where such information came from. But of course he knew, and was pretty proud, secretly, of having such clever animals.

Mr. Bean went on: “Mrs. Bean says: ‘Mr. B.,’ says she, ‘don’t you let those animals go up to Camphor’s alone.’ ‘Well, Mrs. B.,’ says I, ‘I figure our Freddy is running this show, and I don’t ever interfere with him. If he wants my help he knows he can ask for it and get it.’ ‘But ’cordin’ to what I hear,’ she says, ‘this rapscallion Eha is going to try to get our place next.’ ‘And I’ll be ready for him,’ I says; ‘but,’ says I, ‘if Mr. Camphor and this hotel woman’s in trouble, maybe it’s only neighborly for me to traipse along. If they don’t want me, they can tell me so.’”

“And we’re very grateful,” said Mr. Camphor, seizing Mr. Bean’s hand and shaking it again. “Come up on the terrace and we’ll talk it over. Bannister, the twenty-five cent cigars.”

The animals had stood quietly listening. They were bursting with questions for Freddy, but they knew their talk would disturb Mr. Bean and they respected his wishes for they were very fond of him. As the men turned away, they gathered around the pig, but before they could say anything a shrill voice called: “Jimson! Jimson Camphor! What are all those animals doing here?” And they saw Miss Minerva’s gaunt figure striding angrily down towards them.

“Oh, just some friends of mine,” said Mr. Camphor. “Aunt Minerva, may I present Mr. William Bean?”

“How do,” she said shortly. “Are you the—the manager of this menagerie? These are private grounds; you can’t bring these animals in here.”

“Come, come, Aunt,” said Mr. Camphor, “after all, they’re my grounds, and—”

Mr. Bean laid a hand on his arm and winked one eye. Then he turned to Miss Minerva and said with a courtly bow: “My dear lady, I assure you that we are here only to serve you. To protect you from the villain who is plotting to defraud your nephew of his fine property.”

“What villain?” said Miss Minerva. “I know nothing about any plot.”

“Well, there is one,” put in Mr. Camphor, and he told her about Mr. Eha and his schemes.

“Folderol!” she exclaimed. “I never heard such nonsense. You men are all the same: scared of your own shadows and seeing bogies behind every bush. Where is this Eha? Let me talk to him.”

“That’s just the trouble, ma’am,” said Mr. Bean. “We don’t know who he is, or where or when he may strike. However, you have requested me to leave. And a Bean, ma’am, could never refuse the request of so charming a lady. Come, animals!”

The animals of course couldn’t move. They stared at Mr. Bean and their eyes almost fell out of their sockets. For this was a Mr. Bean they didn’t know. These polished manners, these lavish compliments—they could hardly believe their ears.

Miss Minerva’s face relaxed into what might have been the beginning of a smile, and she looked sidelong at Mr. Bean. “Well,” she said slowly, “if you put it that way …”

“I do put it that way, ma’am,” he replied firmly. “That is exactly how I put it. A charming and cultured lady like yourself—who am I to refuse your lightest request?”

Miss Minerva really smiled now. “Flatterer!” she said, and squeaked faintly with pleasure, and she continued to look curiously at him.

But nobody ever found out anything about Mr. Bean by looking at him. Behind those whiskers he might have been handsome or plain, he might be smiling or scornful—nobody ever knew, not even Mrs. Bean.

“Come, animals,” he said again.

“Wait!” said Miss Minerva. “Perhaps—perhaps I have been too hasty. Come,” she said, putting her hand through his arm, “let us go up on the terrace and you can tell me more of this plot.”

“Well, great day in the morning!” said Mr. Camphor, staring after them.

Mrs. Wiggins laughed her comfortable laugh. “I told you you’d get along better with her if you’d pay her a compliment once in a while,” she said.

Mr. Camphor closed his eyes a moment in intense thought. Then he opened them and said to the butler: “Music hath charms to soothe the savage breast. I think that proverb about covers it, eh, Bannister?”

“No doubt, sir, if you can classify that voice as music. And on the other hand, there’s this one: Fine words butter no parsnips.”

“Ha,” said Mr. Camphor; “Aunt Minerva’s no parsnip, but I’d say he buttered her up all right.”

The animals had surrounded Freddy and were talking and laughing and congratulating him on his capture of Ezra. “Hurrah for Freddy!” they shouted. “He brings ’em back alive! Freddy always gets his animal.” Jinx pushed through the crowd. He put a paw on the trap and peered in at the rat, who squeezed back into a corner. “What you got in this birdcage, Freddy? Pretty little thing, ain’t he? Can he sing?”

“Like a thrush, Jinx; like a thrush,” said Freddy. “Want to hear him? Give us a song, Ez.”

“Aw, you think you’re awful funny,” Ezra snarled. “You just wait till Mr. Eha gets here, you big stuck-up—Ouch!” he squeaked. “You quit that!” For Jinx had reached through the wires and cuffed his ear.

“You hadn’t ought to do that, Jinx,” said Mrs. Wiggins.

“Well then let him quit calling names, the grimy sneak,” said Jinx.

The rat sneered at him. “Who’s calling names now? If I wasn’t in a cage, you wouldn’t talk so big.”

“Oh, shut up, both of you!” said Freddy. “Now look, animals. Mr. Eha is going to make plenty of trouble for all of us if we don’t stop him. Once we know who he is, we can pepper his hash all right. So I’m going down to Centerboro and find out. Georgie, I need your help; will you go with me?”

“Gee, you bet I will!” said the little brown dog.

“All right. We’ll see if Bannister will drive us down, to save time. And the rest of you—my goodness, I’m glad you came up today; you’re going to be needed. Until I get back, the main thing is to see that Ezra doesn’t get away. And keep an eye out for Simon and the rest of the gang. I have a hunch they’re around here somewhere, and they might try a rescue.”