Chapter 11

Freddy didn’t know just what he might get into in Centerboro, and he thought it would be better if nobody recognized him. So he borrowed a derby hat and a dark suit from Mr. Camphor, who was really just about his size. With these on, and carrying the medicine case marked Henry Hopper M.D., he could easily have been taken for an undersized medical man, just going out on a call.

He gave Georgie his instructions and posted him at the door of Dixon’s Diner, and then he went in and sat at the counter and ordered a cup of cocoa. It wasn’t dinner time yet, so there were no other customers.

Mr. Dixon was a little round worried looking man. He put the cocoa in front of Freddy and said: “Stranger in town?”

“What do you think?” said Freddy, and took off the derby.

“Why, you’re Freddy!” said Mr. Dixon. “Good gracious me—you investigating another crime?”

“Ssssssh!” said Freddy, putting the derby back on. “Not a word! Yes, a very serious crime, and I think maybe you can help me. Ever hear of a Mr. Eha?”

“Eha?” said Mr. Dixon. “That ain’t a name. It’s a laugh, ain’t it, like Ha-ha! or O-ho-ho!?”

“It may not be his real name,” Freddy said. “But I can tell you something else about him: he’s been coming in here and eating, and then sneaking out without paying his check. I found these unpaid checks in his pocket.” Freddy spread them out on the counter.

“I’ve got some customers that do that,” said Mr. Dixon. “I guess I don’t watch them as carefully as I should.” He examined the checks. “Let’s see—corned beef and cabbage on the eighteenth—that was Friday. Now who had corned beef Friday? Judge Willey did, but he wouldn’t skip without paying. So did Mr. Beller. H’m. Let’s try another—there’s too many of ’em like corned beef. Here, now—pigs’ knuckles and sauer …” He broke off suddenly and slipped the check under the others. “Let’s—er, let’s see this one,” he said hastily. “The twenty-first, Monday; a double order of fresh caviare. Ah ha! I know who had that! It was—” He stopped short again. “No,” he said. “No, I can’t tell you who that was.”

“You mean you won’t.”

“Look, Freddy,” said Mr. Dixon, lowering his voice, although there was no one else in the diner, “there’s some folks I can’t afford to have mad at me. I know who this is. He does it a lot. But I dassen’t say anything to him. I let him get away with it rather than have a fuss. And if you’ll take my advice, you’ll lay off him too. He’s a tough baby; he’d shoot you as soon as look at you.”

Freddy knew he wasn’t going to get anything more out of Mr. Dixon—the man was too scared of Mr. Eha. “Maybe you’re right,” he said. “Let’s skip it. I think I …” He swung round on his stool. Outside, Georgie was barking—three barks, then two; bow-wow-wow, bow-wow, bow-wow-wow, bow-wow. “Whoops!” said Freddy, and grabbed his medicine case and dashed out of the door.

Main Street was full of people, but there was Georgie, following a tall man in a dark suit. And as Freddy caught up, he realized that a strong smell of mothballs was also following the tall man.

The dog dropped back when he saw Freddy. “You know who he is?” he asked.

“Never saw him before. We’ll follow along and see; he certainly smells right.”

“I think he might have come in on the eleven o’clock bus,” said the dog. “He came from that way.”

They followed him to a house on Elm Street before which a lot of cars were standing. Other people were coming up the street and turning in there, and Freddy motioned Georgie to wait by the gate and followed the man up the steps and to the door, which was opened by a maid in a little cap and apron. They went into the hall, side by side. The maid took the man’s hat from him, and then held out her hand for Freddy’s derby. And Freddy realized that he couldn’t take it off. If he did, he would be recognized, and even if he wasn’t thrown out, everybody would know that an uninvited detective had got in.

Looking through the doorway into the parlor, Freddy saw a lot of people all standing around laughing and talking at the top of their lungs, and at the far end flowers and potted palms were banked up. The man went in and began shaking hands with people. And the maid said sharply: “Your hat, sir?”

“I’m a—a Quaker,” said Freddy quickly. “You ought to know, my girl, that Quakers never take their hats off in the house. Look at Benjamin Franklin.”

“Where?” said the girl, peering into the other room.

“Skip it,” said Freddy. “Look here, wasn’t that Mr. Alfred Beagle that came in with me?”

“No sir, that was Mr. Platt, the bride’s uncle.”

“Lives on upper Dugan Street?”

“No, sir; he came from Tushville for the wedding.”

The maid turned away to open the door for some other guests, and Freddy watched Mr. Platt. “Wish I could get my hand in that coat pocket,” he thought. “I wonder if he really is Mr. Eha? He smells pretty strong for just three mothballs. I’ve got to get into that room, but I can’t with this hat on.” Then he had an idea, and when the maid’s back was turned he darted quickly up the stairs.

In the upstairs hall he listened. There were voices in one room; he slid by the door and popped into the one next to it. It was empty. He shut the door and listened, and as he did so, he heard someone start to play the wedding march on a piano, and then the people in the other room came out and started downstairs. “I wonder,” he said to himself, “what’s in that closet?”

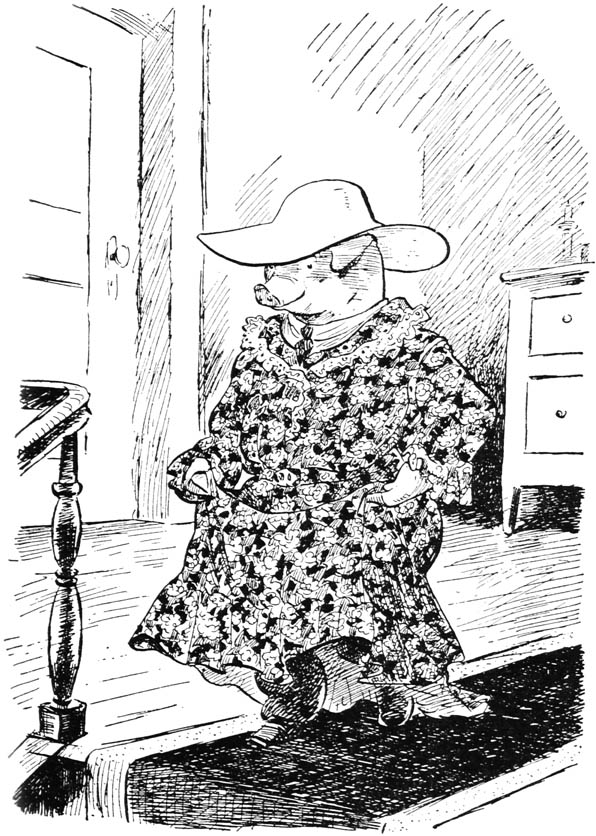

Five minutes later Freddy came downstairs. He wore a dress with big roses all over it which he had pulled right on over Mr. Camphor’s suit. Instead of the derby, which, with the medicine case, he had dropped out of the open window, he wore a large floppy garden hat. The wedding ceremony had started; nobody paid any attention to him as he teetered into the parlor in his high-heeled shoes and worked his way slowly over towards where Mr. Platt was standing.

Five minutes later, Freddy came downstairs.

The ceremony went on. A tall woman, standing beside him, bent down and whispered: “Doesn’t Janey make a lovely bride?”

“Never saw her look lovelier,” Freddy whispered back truthfully.

The tall woman sniffed and touched her eyes with her handkerchief. “So sad, I think, weddings,” she said.

Freddy thought he’d better sniff too, as most of the women in the room seemed to be doing it. Unfortunately, his handkerchief was in his pants pocket, and he couldn’t get at it without causing a lot of notice. But two or three of the guests were now crying pretty hard, so he gave a couple of good loud sobs in order not to be conspicuous.

And then the ceremony was over, and the people began milling around, and everybody was gay again. Freddy couldn’t figure it out. But he didn’t have any time to try. He followed Mr. Platt, who pushed through the crowd and kissed the bride.

“Oh, Uncle Joe,” she said, “I was so afraid you wouldn’t come! When you wrote that you didn’t have a decent suit to wear—goodness, you could have come in your overalls—you know it wouldn’t make any difference to me.”

“Didn’t have to,” said Mr. Platt. “Fred Bullock lent me this suit—it’s the one he was married in, and hasn’t been out of the trunk since. Kind of a wedding suit, I guess you’d call it. We just slid the mothballs out of it and slid me into it, and here I am.”

“Oh, that’s what I smell!” she said. “I thought it was some new kind of soap.”

“We didn’t have time to air it much,” said Mr. Platt. “I kind of like the smell myself.”

“Well,” she said, “I don’t. But no matter how you smell, you’ll always be my favorite uncle.”

“Darn it,” Freddy thought, “this can’t be Eha either. I’d better get out of here.” But before he could slip away, the bride had flung her arms around his neck and kissed him on the cheek. “Oh, mother,” she said, “wasn’t it lovely? But why this dress?—I thought you were going to wear the other …” She broke off and pushed him away. “Why, you’re not my mother!” she exclaimed.

Freddy realized what had happened. The dress he had got into upstairs must be one belonging to the girl’s mother. He’d better do something quick! “Sssssh!” he whispered. “Not a word here! Meet me upstairs in five minutes and I’ll explain.”

He got away while she was still thinking over what he had said. But he didn’t go upstairs. He went down cellar. In the little laundry he stripped off the hat and dress. There was a window over the tubs; he climbed up on the tub rim and unlatched it. And there, right outside and within reach, were his derby and the medicine case.

In another minute or so he would have been outside with them. But someone was coming down the cellar stairs. And while pigs are swift and agile on level ground, climbing is not their stuff. Freddy reached out and grabbed the derby, put a dent in it, crammed it on the back of his head, and when a large woman in an apron who might have been the cook came into the laundry, he was kneeling with his back to her, examining the waste pipe under the tub.

“Well!” she said. “How’d you get in here?”

“Same way you did—down them stairs,” said Freddy in a hoarse voice. “Look, missis; there ain’t anything the matter with that there drain. Why don’t you make sure it’s plugged before you go callin’ me up? I’m a busy man.”

“What are you talking about?” said the woman. “Nobody called you to fix any drain.”

“Certainly did. Said hurry up over to 83 Elm Street and …”

“This is 22 Elm Street,” she interrupted.

“What?” said Freddy, starting up. “Lordy, lordy, how’d I get in here? I got to get over to 83—they’ll skin me alive for taking so long.” And he pushed past the woman and up the stairs.

Outside, he picked up his medicine case and met Georgie at the gate. “Wrong man,” he said. “We’ve got to get back to the diner.”

“OK,” said the dog. “Wipe that lipstick off your face first.”

“Lipstick?” said Freddy. “Oh, I must have got that when the bride thought I was her mother.”

“She thought you were her mother? With a derby hat on?” said Georgie. Of course he hadn’t seen Freddy in the woman’s dress and hat. And he began to giggle. “Don’t give me that stuff! And don’t give me any bride, either. I saw you through the cellar window. Boy, if Jinx ever gets hold of that you’ll never hear the last of it. Kissed by the cook! I bet she thought you were cute!”

“Well, it wasn’t the cook,” said Freddy. “And if you go making up any stories, I’ll tell ’em about the time that little girl that visited the Beans tied a pink ribbon around your stomach and talked baby talk to you. ‘Oh, oo twe-e-et ickle itsy-bitsy pupsy wups! I kiss’m and hug’m and kiss’m and hug’m.’ Wasn’t that it?”

“OK,” said Georgie. “You win. I didn’t see a thing.”

It was about noon now, and people were beginning to go into the diner to get their dinner. Freddy stood across the street and watched Georgie, who took up his post beside the door. As each new arrival turned in, the dog would run up to him, wagging his tail. Nearly everyone would say a word to him, or stoop to pat his head, and he had a chance to get a good sniff at their pockets. He smelt a lot of different things—tobacco, peppermint, peanuts, hair tonic; Mr. Beller smelt of fried onions, Judge Willey—rather surprisingly—of bubble gum. But no mothballs—until Mr. Anderson, the real estate man, went in. Georgie took one sniff and ran across the street to Freddy. “Got him,” he said. “What do we do now?”

Freddy said: “That’s funny. He’s about the right height for Mr. Eha, but he’s an important citizen. Doesn’t seem like the kind that would be playing silly ghost tricks.”

“That’s your problem,” said the dog. “He smells of mothballs, that’s all I know.”

“We have to investigate him, then,” said Freddy. “If he’s our man, there are three mothballs in the upper outside pocket of that coat.”

“When he comes out,” said Georgie, “suppose I run between his legs and trip him up, and then old Dr. Hopper comes along and feels him over for broken bones, eh?”

“Sure. I could feel of his heart to see if it’s still beating. That pocket is right over his heart. That’s an idea, Georgie.”

They had to wait about half an hour. Then as Mr. Anderson came out and started up the street, Georgie darted after him. Freddy followed more slowly. The dog trotted along beside Mr. Anderson, waiting for a chance to trip him. But Mr. Anderson did not like dogs. He turned and aimed a kick at Georgie which would certainly have broken a rib or two if it had landed square. But Georgie ducked, and the toe of the shoe caught him a glancing blow on the shoulder that shot him out into the street. Mr. Anderson just walked on.

Georgie picked himself up and came back to Freddy. “No use feeling of that guy’s heart,” he said. “He hasn’t got any. The big bully, he might have killed me.”

“I guess we’ll have to be more careful,” Freddy said. “He plays kind of rough. We’ll wait a while and then go up to his place. I’ve got an idea.”