Chapter 15

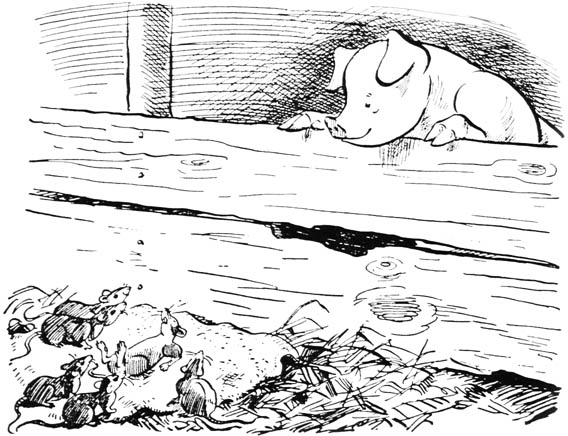

Freddy was up early next morning. It was a dull drizzly day, and he shivered as he hurried down to the stable to take a look at the prisoners. They were locked up in the box stall next to Hank’s, and guarded by Jacob, the wasp, and two of his cousins. Simon was asleep on an old grain bag and breathing heavily, but the others were awake, and they stared at the pig anxiously with their beady black eyes, but didn’t say anything.

Jacob flew down and lit on Freddy’s nose. “Everything’s under control,” he said. “Caught one of ’em starting to gnaw through the wall a while back, but I guess he won’t do any more gnawing for a while. Had to give him a little touch of the old needle. My, my; such language as he used!

“Tough, he was, too,” Jacob went on. “Afraid I blunted my sting on his thick skull.” He slid it out and placed the point on the tip of Freddy’s snout. “Mind if I just try it a mite here? I won’t hurt you.”

Freddy thought Jacob was joking, but it was hard to tell, for wasps only have one expression on their faces, and even that one doesn’t express anything. “No!” he said. “Lay off, Jacob!” He stared apprehensively at the wasp, and some of the rats began to giggle.

Jacob leaped into the air and droned in a circle above their heads. “None of that!” he buzzed. “You show a proper respect for your betters if you know what’s good for you.”

“Oh, please, Mr. Jacob,” said one of them; “we didn’t—we weren’t laughing at you. It was Mr. Freddy—he looked cross-eyed at you.”

“Why, I did nothing of the kind,” said Freddy.

“Oh, excuse me, sir,” squealed the rat. “I guess you had to look cross-eyed to see him, because he was on the end of your nose.”

“Oh,” Freddy said. “Well, maybe I did.” He frowned at the rat. “Aren’t you the one that bit me last night?”

“Well, sir—I …”

“Answer yes or no, please,” said Freddy, putting on his Great Detective expression.

“Well, I—yes, I did. But you sat on me, afterwards.”

“I see. You mean we’re even. Maybe you’re right. Although—Oh, good morning, Jinx,” he said, as the cat pushed open the stall door.

“Just dropped in to see if the condemned man was eating the usual hearty breakfast,” said Jinx. He went over and sat down by Simon. “How’s old poisonous this morning?”

Simon opened one eye, then closed it again.

“Let him alone, Jinx,” said Freddy. “He’s got trouble enough coming to him when he gets well. Come on out; I want to talk to you.”

They went out into the barnyard. Charles was just coming across from the henhouse, and Jinx hailed him. “Hi, Charlie, old fighting cock! You certainly put up a great scrap last night. I saw you in there, stomping and gouging and ripping off arms and legs, and I said: Boy, there’s a rooster that could lick his weight in lollipops, and …”

“Oh, shut up!” said Charles crossly. “You know very well I wasn’t there last night. I—well, with this farm invaded by hordes of ferocious rats, would you have expected me to leave my home, my dear wife, and twenty-seven children, totally unprotected? Much as I would like to have been with you, to have stood shoulder to shoulder with my comrades in the fray, my duty confined me to the henhouse. Yes, my friend, the heart that beats beneath this feathered bosom is no craven’s; it …”

“Boloney!” said Jinx. “It was your dear wife Henrietta that confined you to the henhouse, chum, so you wouldn’t get those handsome tailfeathers chewed off. Don’t give us that shoulder to shoulder stuff, and you can cut out the feathered bosom, too.”

Charles hung his head, and Freddy felt sorry for him. The rooster was a braggart, and badly henpecked by his wife, but he wasn’t really a coward. He had once licked a rat in fair fight, and a year or so ago he had gone into Herb Garble’s office in Centerboro and cleaned it out singlehanded. “Charles,” said Freddy, “how’d you like to go up to Mr. Camphor’s with me tomorrow? We’ve got to do something about those aunts of his, and maybe you could help.”

Charles perked up at once. “Command me,” he said magnificently. “It is a pleasure and a privilege to serve Mr. Camphor.”

So the next morning they started out. It was still raining, but though animals don’t mind rain as much as people do, Freddy carried Mrs. Bean’s old plum-colored umbrella. “It won’t do to go into Mr. Camphor’s spick and span parlor all dripping wet,” he said. “And Miss Minerva would have a fit.”

Freddy carried Mrs. Bean’s old plum-colored umbrella.

“She’ll have a fit anyway,” said Charles.

“That’s up to you,” Freddy said. “That’s why I wanted you to come. You think up your floweriest compliments for her.”

They were pretty wet though when they got there. Bannister brought them bath towels to dry off with before they went into the parlor, and they were scrubbing themselves when Miss Minerva appeared.

“My land!” she exclaimed. “You’re dripping all over the rug! Why do you have to come up here on a day like this?”

“Madam,” said Charles, “only the anticipation of seeing you again so soon could have induced us to brave the inclemency of the elements.”

“Well …” said Miss Minerva doubtfully.

“Your gracious presence, ma’am,” the rooster went on, “transforms the gloomiest hours to a day of sparkling sunshine and balmy breezes. In the light of your charming smile the clouds disperse, the sun breaks through, the world is all brightness and glitter.” He bowed deeply.

And a smile did indeed appear on Miss Minerva’s face. It wouldn’t have dispersed any clouds, nor could you have recognized it from Charles’ description, but it was a smile. “Come into the parlor,” she said.

Mr. Camphor had news. The sheriff had phoned to say that Mr. Anderson was sick in bed, but was expected out in a day or two. “Guess he has a hard time getting comfortable, though,” the sheriff had said. “Porky quills in front and bird shot in the rear—has to sleep on his side.”

“Well, that’s nice,” said Freddy. “But it isn’t really any good. For though we’ve broken up his scheme for getting your house and the Beans’, he has got the hotel.”

“Come out on the porch,” said Mr. Camphor, and when they had followed him out there: “Listen,” he said.

The rain had let up, and from across the lake they could hear a faint sound of hammering.

“Carpenters,” said Mr. Camphor. “Plumbers. He’s got them repairing the hotel already. According to the sheriff, he is going to move up there himself as soon as he’s well enough. It’s a shame. But what can we do?”

“I think …” Freddy began. But a voice from the end of the porch interrupted him. “Come here,” it said. He looked, and there was Miss Elmira in her chair, wrapped in shawls and gazing out gloomily at the grey lake.

He went over to her and Charles strutted after him, but Mr. Camphor disappeared in the house.

“Poem,” said Miss Elmira.

“I haven’t written any other gloomy ones yet,” he said.

“Swamp,” said Miss Elmira.

“Oh, you want that one again? All right.” And he recited it, with appropriate sobs and sniffs.

Miss Elmira laughed even more heartily than before, but Charles, who had listened with one claw covering his eyes, broke down and wept bitterly. “Oh! Oh, dear! Oh, dear me!” he said brokenly. “Oh, the sadness! Oh, my desolate heart! How mournfully beautiful! What a masterpiece of despair!”

Freddy thought the rooster was overdoing it, and shook his head at him, for Miss Elmira had stopped laughing. She looked almost disapprovingly at Charles. “Always like that?” she demanded.

“Always,” said Freddy. “Always wallowing in woe, soaked in sorrow, fricasseed in affliction. Worst case I’ve ever known.”

Charles went on sobbing.

Miss Elmira’s shoulders twitched impatiently. Then she said: “Go away.”

“Of course,” said Freddy. “Come, my poor fellow,” and he supported the weeping Charles into the house.

The rooster straightened when they were inside the door. “That was a terrible poem, Freddy,” he said. “If I couldn’t write a better one with one claw tied behind my back …”

“Oh, you’re a wonder,” said Freddy sarcastically. “You fixed things fine with all that bawling! She knew you were making it up.”

“On the contrary,” said Charles. “She was mad, all right, but it was because she had met someone who is gloomier than she is. You’ve got her all wrong. She doesn’t want other people to be gloomy. She wants to be the gloomiest person in the house, herself. What do you suppose she stays here for, if everybody is always trying to cheer her up? She likes it. She wouldn’t stay a minute if everybody sobbed and howled all day long.”

“Oh, pooh,” said Freddy; “that doesn’t make sense.”

“Yeah, just because you didn’t think of it!” said Charles angrily. “All right, have it your way. But if Camphor wants to get rid of her, he’d better let me handle it, that’s all.”

Freddy really thought that maybe Charles was right, but he knew that if he took up the idea himself the rooster would just sit back and not do anything. So he continued to pooh-pooh the theory until Charles got really mad and said that by George, he’d show them, and stamped out of the house.