Chapter 16

Freddy went in and had a long talk with Mr. Camphor, and at his pressing invitation, stayed for lunch. “I really want you to see, Freddy,” Mr. Camphor said, “what a change a few compliments have made in Aunt Minerva. Nothing burned, no bawlings out; and she made a batch of peanut brittle last night that—m’m!” He blew a kiss in the air. “It would melt in your mouth!”

So Freddy stayed. A place was set for Charles, but when Bannister announced lunch the rooster couldn’t be found, so they sat down without him. When Miss Minerva came in, Freddy pulled out her chair for her, and she rewarded him with a smile. At least it was intended for a smile. She really just showed her teeth at him. But it wasn’t fair to be too critical of it, Freddy thought, because probably she hadn’t really smiled in a good many years, and she needed practice.

The soufflé was good, the chocolate pie was delicious. “The nectar of the gods!” Mr. Camphor exclaimed with his mouth full, and was not reproved for it. Freddy smacked his lips and said: “M’m! M’mmm!” all through the meal. Miss Minerva became quite sprightly.

“She doesn’t pick on me any more either,” Mr. Camphor said later. “I used the wrong fork at dinner last night, and she didn’t say a word.”

“Then do you still want her to go?” Freddy asked.

Mr. Camphor thought a moment. “Really, you know,” he said, “I don’t believe I do. I haven’t eaten so well in years. But of course there’s Aunt Elmira. Look at her there through the window. What’s the good of having Aunt Minerva cooking for me if Aunt Elmira takes away my appetite?”

“I’ve got to give some thought to that,” said Freddy. “Also to Mr. Eha. We’ve broken up the rat gang all right, and I guess he realizes that the ghost act won’t get him anywhere. But he did get the hotel away from poor Mrs. Filmore. I think we ought to get it back for her.”

Mr. Camphor shook his head. “Nothing can be done about that now. We’ve got her a job, though. I used my influence with Mr. Weezer, in the bank, and they’ve taken her on at a small salary.”

“That’s fine,” said Freddy. “But Eha’s got the hotel, and I don’t see why we can’t use the same tactics against him that he did against Mrs. Filmore. Not rats and ghosts, of course—I’ve got a better idea.” He looked thoughtfully at Mr. Camphor. “How’d you like to go camping again?”

“Oh, I’d like that!” said Mr. Camphor enthusiastically. “We didn’t have much of a go at it before. Ha, the wide open spaces! The mysterious silence of the great forest! The wind shushing through the pines …”

“And the mosquitoes whining through the brush,” said Freddy. “Yeah, it’s pretty nice. But this will be something more than a camping trip. It’ll be an anti-Eha expedition. A war party.”

“Ha, Camphor takes the warpath, eh? Let’s practice our warwhoop.” And he gave a loud yell, batting his open palm against his mouth—“Wa-wa-wa-wa!”

“I don’t think the Indian warwhoop went like that,” Freddy said. “It was more like this.” And then he yelled: “Yi-yi-yi-yi!”

“What on earth are you doing?” said Miss Minerva, coming to the door. She looked at them rather severely, but didn’t fly out at them. And when Mr. Camphor had rather shamefacedly explained, she astonished them by saying: “You’re both wrong. Grandfather showed me. This is the way it went,” and she threw back her head and gave a terrific screech: “Eeeee-yow!”

“Golly,” said Mr. Camphor; “you win, Aunt. Say, how’d you like to go along on this expedition? You used to camp out with grandfather, years ago.”

“Oh, I don’t know,” she said. “I—well, I suppose Bannister could look after Elmira … H’m … Very well,” she said quickly. “I’ll come.”

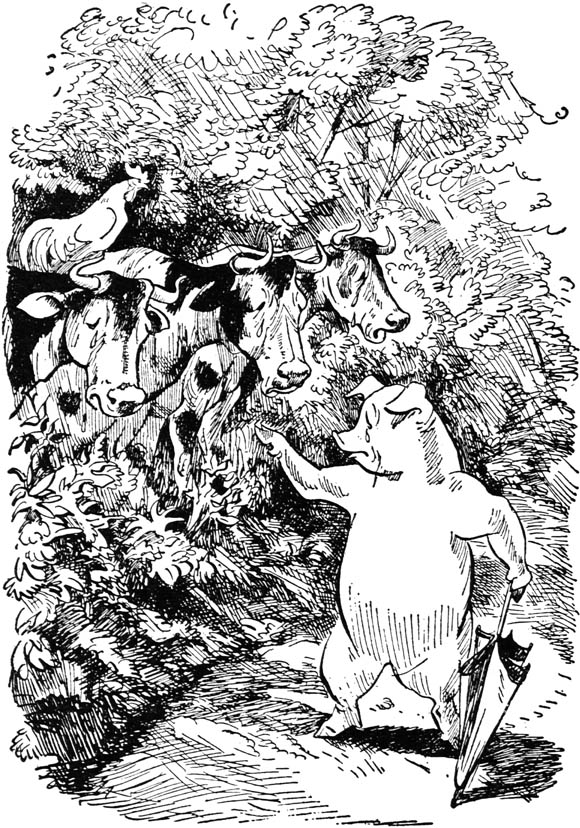

Freddy wasn’t too well pleased with this but there was nothing he could do. After lunch he started back to the farm. The rain had stopped. Going down through the Big Woods he heard voices, and then Mrs. Wiggins’ broad white nose pushed through the underbrush, and she came towards him, followed by her two sisters. Charles was riding on Mrs. Wurzburger’s back.

“Where you going?” Freddy asked. “And where’d you go to, Charles? They expected you for lunch.”

Mrs. Wiggins laughed. “We’re going up to call on Miss Elmira. It’s Charles’ idea. He thinks if everybody she sees is gloomier than she is, she’ll either snap out of it, or leave. And we’re good at grief, eh, girls?”

Mrs. Wogus and Mrs. Wurzburger nodded. Then all three cows looked sadly at Freddy, and pulled their mouths down, and fat tears welled out of their big brown mournful eyes and splashed on the ground.

Freddy looked at them a minute, and then he felt the corners of his own mouth droop, and a tightness behind his eyes and a stinging in them, and he said: “Hey, quit it, will you? Darn it, you’re m-making me do it, too! I can’t … Well, goodbye,” he said and pushed quickly past them.

“Hey, quit it, will you … you’re m-making me do it, too!”

He went into the cowbarn and yelled for Mr. Webb, and pretty soon a little black spider came spinning down on a strand of gossamer and landed on his ear. “Hello, Freddy,” he said in his tiny voice. “You know, Mother and I are kind of put out that you haven’t called on us for any help in all this excitement. After all, the Bean farm is our home just as much as it is yours.”

“Well,” said Freddy, “we can use you now all right. Look, can you and Mrs. Webb round up about fifty crickets, and as many fireflies, and some grasshoppers and a centipede or two? Just get those that are willing to volunteer for foreign service; I want their help up at Camphor’s, but only if they want to go.”

“Round up a bushel of ’em if you say so, Freddy. My! Won’t Mother be tickled! She says she’s sick and tired of sitting up there in the roof spinning, spinning, all day long, while all these exciting things are going on. And catching a few flies. Even the flies, she says, aren’t what they were in her young days—horrid skinny things, and half of ’em full of DDT.” Mr. Webb laughed. “You know and I know, Freddy, that flies aren’t any different. Never was much nourishment in ’em anyway. But you know how women are.”

“Sure,” said Freddy. “Well, have your gang in here at four o’clock, eh? I’ll tell you what we’re going to do later.”

Actually, Freddy had only the vaguest idea of what he was going to do. Harass Mr. Anderson, and try to drive him out of the hotel as he had driven Mrs. Filmore. But just how? Oh well, he could always think up seven different ways of doing something.

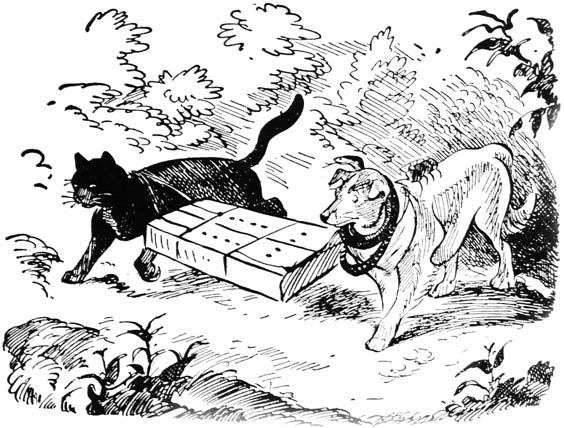

It was certainly an odd expedition that started from the farm at four o’clock. Freddy and Jinx and Georgie, a snake friend of Freddy’s named Homer, the four mice, and a large flat carton lined with moss, containing the insect volunteers. Among these were Randolph, the beetle and his friend the thousand-legger, Jeffrey. Several wasps who were not needed to guard the rats, and Mr. and Mrs. Pomeroy, would join them next day.

Freddy and Jinx carried the carton between them. It was light, but it made hard going where the ground was rough. The Webbs rode in the carton to keep the volunteers in order. The mice rode on Georgie’s back, and Homer was looped about his neck. Homer had been present on the occasion when the little girl visitor had made Georgie look silly by talking baby talk to him; and like a good many snakes, he thought that a good joke never wore out. He would coil himself affectionately around Georgie’s neck, and then twist himself around in front until his nose was almost against Georgie’s. “Who’s urn’s ickle dolling pupsywups?” he would say in a little sickly-sweet voice, and kiss Georgie on the nose.

Every time he did this, the mice would get to giggling, and that would make Georgie even madder. He would snap at Homer, but the snake was too quick, and would dodge and then whip his coils so tight around the dog’s neck that his eyes bulged. “I hug’m and kiss’m and hug’m and kiss’m,” said Homer. Cousin Augustus giggled so hard he got the hiccups.

At Mr. Camphor’s, while the canoe was being loaded, Freddy and Jinx went around to the porch. Miss Elmira was still there, and around her sat the three cows. They weren’t saying anything. They just sat there, looking as mournful as possible. They stared at Miss Elmira with their great sad eyes, and every now and then one of them would give a low moo of despair. Charles was with them, his tailfeathers drooping, a small pocket handkerchief held to his eyes with one claw.

Miss Elmira too, of course, was draped and enveloped in gloom, but Freddy thought she was looking a little impatient. He said to Bannister, who had come out and was looking over their shoulders: “Looks to me as if she was beginning to get enough.”

The butler gave a faint sniffle. “Ah, sir,” he said, “a great tragic actress was lost to the world when Mrs. Wiggins became a cow.”

“Pooh,” said Jinx; “she’s good all right-I’ll hand you that. But there’s more to acting than just sitting still and mugging. An actor acts. You got to give ’em action. Watch me.”

He walked over and stood between Mrs. Wiggins and Mrs. Wurzburger. “Ma’am,” he said, “you may think you got trouble. You may think you got afflictions that make a monkey out of Job. But listen to me. A: my father was killed by a flatiron last week when he was conducting a backyard concert. B: my mother died of grief. C: my wife and seven children were tied up in a sack and drowned by a wicked butler.” He began to pace up and down. “D: I’ve got rheumatism, hives and hay fever. E:—” Evidently he couldn’t think of anything for E, for he sat down, lifted up his head, and began to wail.

There is no use trying to describe those wails. Multiply any cat you’ve ever heard by ten, and add a few assorted owls, and you might get somewhere near it. They quavered and soared and broke into despairing gobblings, and then rose to a screech again. Mr. Camphor and Miss Minerva came rushing out. “What on earth!” Miss Minerva exclaimed. She looked at the circle of weeping animals about her sister. “Is it—is it something they had for lunch?”

“My goodness, I don’t know where you could get anything for lunch, except maybe live scorpions, that would make them act that way,” said Mr. Camphor.

Freddy explained to Miss Minerva what they were trying to do. But she shook her head. “You may be on the right track. We’ve always been very cheerful with her, and maybe being gloomy might change her. But even as a little girl she was like this. Used to give each of her dolls a handkerchief when she put them to bed, so they could cry in the night. She just wants to be miserable. She can walk around as well as I can, you know. She stays in the wheel chair because it makes her feel like an invalid. I guess having her around like that is what makes me so impatient with Jimson sometimes. I’ve felt I had to be so extra nice to her.” She looked speculatively at her sister. “Well, you animals are so anxious to help, the least I can do is join in.”

She took out her handkerchief and went over to her sister, wiping her eyes. “My poor Elmira,” she said, “how fortunate that you are no longer alone in your sadness. What a blessing that there are others—many others—who are even more sorrowful and despondent than you are!”

“They are not!” snapped Miss Elmira. She had been getting more and more restless, and with the words she sat up in her chair.

“EE-e-eeyowl-er-owl!” wailed Jinx.

“When in Rome, do as the Romans do,” said Bannister, and fell sobbing on Mr. Camphor’s shoulder.

Miss Elmira stared around defiantly at the grief-stricken group. She seemed very much disturbed, and Freddy began to feel that Charles had been right. She had always held the center of the stage, as the hopelessly sad person who had to be deferred to and coddled. But now she was just one of the chorus, one among many, all of whom seemed more startlingly dismal than she was.

“She’s not the queen bee any more,” he thought. “She’s like sick people, who feel important because everybody else in the house waits on them, and then they go to a hospital where everybody is sick, and they don’t like it.” Then he was aware that she was beckoning to him.

“That swamp,” she said when he went over to her. “Where is it?”

“You mean the swamp I wrote the poem about? Why, I guess I was thinking of the Great Dismal Swamp. It’s in Virginia, isn’t it?”

“Bannister,” she said, “place reservation to nearest point.”

“Yes, madam,” said Bannister, taking out his notebook. “Bus from Centerboro to Rome, plane from Rome to nearest point touching the swamp. I’ll look that up, madam.”

Miss Elmira said: “I’ll pack my bag,” and got up and followed him as lightly and easily as if she’d been exercising regularly, instead of sitting for days on end in a wheel chair.

“Well, I’ll be darned!” said Mr. Camphor.

“Good gracious,” said Freddy, “do you think she can take a trip like that? You think she’ll be all right?”

“Look at her,” said Mr. Camphor. “In those shawls and with that expression, can’t you see people falling over themselves to give her the best seat in the bus? Everybody will want to help the poor old lady. My goodness, next time I travel, I’m going to put on a long white beard and carry a cane, and then maybe I won’t have to stand up half the way.”

“You do really think she’ll be all right, Jimson?” said Miss Minerva. “I’ve looked after her for so long …”

“Certainly I do. She’ll get herself a little place on the edge of the swamp, and she’ll be as happy as a toad in a mud puddle. Or as gloomy. Matter of fact, maybe she plans to go down there and work up an extra case of gloom and then come back and show us all up.”

Miss Minerva looked out across the lake, and then up at the sky. “Dear me,” she said, “I do believe the sun is going to come out.”

“It does seem brighter,” said Mr. Camphor, “but the clouds are just as heavy.”

“What’s brighter is that Miss Elmira’s gone,” Freddy said.