Franklin, accustomed only to small, provincial, transatlantic towns, lived for a year and a half in the capital of his world in one of its brilliant ages. At peace with France, England had

PHILADELPHIA Journeyman : j /

grown rich and was growing richer. The Hanoverian succession was established, though the Old Pretender plotted futilely in Rome. Men of trade and money challenged the power of the landowning aristocracy. Walpole, canny and corrupt, held the reins of many offices. It was an age of luxury, fashion, and wit. The elegant Stanhope became Lord Chesterfield while Franklin was in London, and Voltaire took refuge there from his enemies in Paris. It was an age of intellect. Newton towered over British science. Bentley, England's greatest classical scholar, wrangled at Cambridge. Hogarth had set up on his own account and had published his first engraving. Fielding, fresh from Eton, was having his fling in London, where Samuel Richardson was a rising printer. Jonathan Wild was hanged in 1725, and Defoe, Grub Street's genius, wrote the rascal's life. Swift in 1726 came back for the first time from his Irish exile. He and Pope and Gay put their heads together in the war against dullness which they carried out in Gulliver''s Travels, The Dmicictd, and Fables.

It was a brilliant age—and Franklin was little closer to it at first hand than if he had been in Boston or Philadelphia. He read and heard of great men, barely saw or talked with them. But the unknown journeyman made friends any way he could. Setting type, at Palmer's, for William WoUaston's earnest treatise The Religion of Nature Delineated, the printer disagreed with the writer and composed A Dissertation on Liberty and Necessity, Pleasure and Pai?i which he printed himself in 1725, apparently during his first half-year in London. WoUaston, in answer to the deists, had attempted to prove with geometrical rigour that even if there had never been a divine revelation there would still be support and reason in nature itself for all the essential beliefs of orthodox religion. Some acts of men, he claimed to prove, are naturally good, some naturally bad, some naturallv indifferent. Franklin, who at fifteen in Boston had been turned to a logical deism by reading the arguments against it, now was turned to an indulgent pantheism.

Since God was all-wise, all-good, all-powerful, and yet permitted the world to be what it was, therefore there could be no such things as natural virtues and vices. Men had no free-will, did what they must, and could not be blamed or praised for their behaviour. What moved them to action was the desire to avoid

^2 : BENJAMIN FRANKLIN

pain and experience pleasure. "I might here observe, how necessary a thing in the order and design of the universe this pain or uneasiness is, and how beautiful in its place! Let us but suppose it just now banished the world entirely, and consider the consequence of it: all the animal creation would immediately stand stock-still, exactly in the posture they were in the moment uneasiness departed: not a limb, not a finger would henceforth move; we should all be reduced to the condition of statues, dull and unactive; here I should continue to sit motionless with the pen in my hand thus—and neither leave my seat nor write one letter more." But pleasure and pain were exactly equal to one another. "The monarch is not more happy than the slave, nor the beggar more miserable than Croesus. Suppose A, B, and C three distinct beings: A and B animate, capable of pleasure and pain, C an inanimate piece of matter, insensible of either. A receives ten degrees of pain, which are necessarily succeeded by ten degrees of pleasure; B receives fifteen of pain, and the consequent equal number of pleasure; C all the while lies unconcerned, and as he has not suffered the former, has no right to the latter. What can be more equal and more just than this?" Since there is no inequality of pain and pleasure in this life, there is no need to imagine another, better life to come. Even though the immaterial soul should somehow persist, it "must then necessarily cease to think or act, having nothing left to think or act upon. . . . And to cease to think is but little different from ceasing to be."^'*

"The order and course of things will not be affected by reasoning of this kind,""^ Franklin broke off to say in the middle of his demonstration. He did not value metaphysics. He was a young Bostonian trying to find reasons for doing as he liked in London. If there were no such things as right and wrong, and no eternal rewards or punishments, what he might do would not matter. He could make himself as free as Ralph already was. The pamphlet was dedicated to Ralph. But the order and course of Franklin's own life cannot have been much affected. He worked hard for long hours every day. He read books from the bookseller's next door to the house in Little Britain. He was too temperate to drink, too economical to gamble. Since the more splendid vices were out of his reach, "foolish intrigues with low

PHILADELPHIA Journeyman : J5

women"-'*' must have been his only dissipations. And it is not certain, though it is likely, that they began in London.

His employer thought Franklin's principles abominable, but he could not help noticing a journeyman who could and would write a book. Franklin printed a hundred copies, gave a few of them to friends, and later burned the rest, "conceiving it might have an ill tendency."-^ One copy reached a surgeon named William Lyons, who often called on Franklin to talk with him, and who introduced him to men of similar opinions. At the Horns, an alehouse in Cheapside, he met Bernard Mandeville, author of The Fable of the Bees, "who had a club there, of which he was the soul, being a most facetious, entertaining companion. Lyons, too, introduced me to Dr. [Henry] Pemberton, at Batson's coffee house, who promised to give me an opportunity, some time or other, of seeing Sir Isaac Newton, of which I was extremely desirous; but this never happened."-^

By his own initiative Franklin met Sir Hans Sloane, who had been secretary of the Royal Society and after Newton's death was to become president. To him Franklin wrote the earliest of his surviving letters, on 2 June 1725. "Sir: Having lately been in the no[r]thern parts of America, I have brought from thence a purse made of the stone asbestos, a piece of the stone, and a piece of wood, the pithy part of which is of the same nature, and called by the inhabitants salamander cotton. As you are noted to be a lover of curiosities, I have informed you of these; and if you have any inclination to purchase them, or see 'em, let me know your pleasure by a line directed for me at the Golden Fan in Little Britain, and I will wait upon you with them." He added what was perhaps a strategic postscript: "I expect to be out of town in two or three days, and therefore beg an immediate an-swer."^^ Sloane called on Franklin, invited him to Bloomsbury Square to see his treasures, and bought the North American curiosities.

Late in 1725 Franklin, now rid of Ralph, left Palmer's for James Watts's larger printing-house in Wild's Court near Lincoln's Inn Fields. Here, though there were nearly fifty printers, he was soon distinguished by his strength and speed. The others carried one large form of types up and down the stairs; he car-

54 : BENJAMIN FRANKLIN

ried two, "They wondered to see, from this and several instances, that the 'Water American' as they called me, was stronger than themselves, who drank strong beer. We had an alehouse boy who attended always in the house to supply the workmen. My companion at the press drank every day a pint before breakfast, a pint at breakfast with his bread and cheese, a pint between breakfast and dinner, a pint at dinner, a pint in the afternoon about six o'clock, and another when he had done his day's work. I thought it a detestable custom."^*^ There was no more strength in a quart of beer, Franklin argued, than in a pennyworth of bread. Let his companion eat that and save his money.

The pressmen, among whom Franklin first worked at Watts's because he wanted exercise, kept on drinking, and he was transferred to the composing room. There the compositors demanded that he pay a kind of initiation fee of five shillings for liquor for all of them. He had already paid for his welcome by the pressmen, and refused to pay again. Though he held out two or three weeks, he suffered from so many "little pieces of private mischief" that he yielded, "convinced of the folly of being on ill terms with those one is to live with continually."^^ At once he became popular and influential. "From my example a great part of them left their muddling breakfast of beer and bread and cheese, finding they could with me be supplied from a neighbouring' house with a large porringer of hot-water gruel, sprinkled with pepper, crumbed with bread, and a bit of butter in it, for the price of a pint of beer, viz., three halfpence. This was a more comfortable as well as cheaper breakfast, and kept their heads clearer."^^ Some of them continued to drink beer, exhausted their credit at the alehouse before the end of the week, and had to depend on Franklin. He claimed what was due him every Saturday night, sometimes as high as thirty shillings, his week's wages. This impressed them, and they enjoyed his satirical tongue. His master, because Franklin was always at work, never late on Monday, and very fast, gave him special jobs and often special pay.

He left his lodgings in Little Britain for a house in Duke Street. His landlady "was a widow, an elderly woman; had been bred a Protestant, being a clergyman's daughter, but was converted to the Catholic religion by her husband, whose memory she much revered; had lived much among people of distinction.

and knew a thousand anecdotes of them as far back as the times of Charles the Second. Shg was lame in her knees with the gout, and therefore seldom stirred out of her room, so she sometimes wanted company; and she was so highly amusing that I was sure to spend an evening with her whenever she desired it. Our supper was only half an anchovy each, on a very little strip of bread and butter, and half a pint of ale between us; but the entertainment was in her conversation."'^'^ When he heard of lodgings nearer his work for two shillings a week, instead of the three and six he paid her, she let him stay for one and six, and he did not scruple to accept her offer. He was saving money to take him back to Philadelphia.

He made friends at the printing-house with a young man named Wygate, who was better educated than most printers. Franklin taught him and a friend of his to swim "at twice going into the river." They introduced him to some gentlemen from the country, and all of them went one day by water to Chelsea, in the late spring or early summer of 1726. "In our return, at the request of the company, whose curiosity Wygate had excited, I stripped and leaped into the river, and swam from near Chelsea to Blackfriars, performing on the way many feats of activity, both upon and under water, that surprised and pleased those to whom they were novelties. I had from a child been ever delighted with this exercise, had studied and practised all Theve-not's motions and positions, added some of my own, aiming at the graceful and easy as well as the useful. All these I took occasion of exhibiting to the company, and was much flattered by their admiration."^^ Sir William Wyndham, friend of Swift and Bolingbroke, heard of the feat, sent for Franklin, and asked him to teach Wyndham's two young sons to swim. Wygate, drawn to Franklin by his skill in the water as well as by his intellectual interests, proposed that they travel throughout Europe as journeymen printers. Both schemes tempted Franklin, but he had grown tired of London and remembered Pennsylvania. And now Denham, the merchant with whom he had crossed the Atlantic, suggested how he might return.

Denham, who had already made one fortune in America, intended to make another, by starting a store in Philadelphia. Franklin could be his clerk at fifty pounds a year, and, as soon

^6 : BENJAMIN FRANKLIN

as he learned the business, could go with a shipload of goods to the West Indies and earn handsome commissions. Though this meant that Franklin would have to give up, as he then thought, the trade in which he was expert, and to work at first for lower wages than a London compositor's, it also meant better prospects. He immediately agreed, and Denham advanced him ten pounds for his passage home. They sailed from Gravesend on the Berkshire 23 July 1726.

IV

(So far in this history, Franklin, speaking of himself in his own words, has almost always spoken in the words of the Autobiography which he wrote forty-five years after the departure from Gravesend, when he was sage and famous, and writing for his son, the governor of New Jersey. Perhaps then he tempered the account of his youth, saw his course as straighter than it was, left out or had forgotten his ranker appetites, remembered too clearly the mind and will which had outlasted the lost years. But now he speaks as he wrote at twenty in the journal he kept of his summer voyage.^^)

''''Friday, July 22, /72<^.—Yesterday in the afternoon we left London and came to anchor off Gravesend about eleven at night. I lay ashore all night, and this morning took a walk up to the Windmill Hill, from which I had an agreeable prospect of the country for above twenty miles round, and two or three reaches of the river, with ships and boats sailing both up and down, and Tilbury Fort on the other side, which commands the river and passage to London, This Gravesend is a cursed biting place; the chief dependence of the people being the advantage they make of imposing upon strangers. If you buy anything of them, and give half what they ask, you pay twice as much as the thing is worth. Thank God, we shall leave it tomorrow.

''''Saturday, July 25.—This day we weighed anchor and fell down with the tide, there being little or no wind. In the afternoon we had a fresh, gale that brought us down to Margate, where we shall lie at anchor this night. Most of the passengers are very sick. Saw several porpoises, etc.

'^Sunday, July 2^.—This morning we weighed anchor, and coming to the Downs, we set our pilot ashore at Deal, and passed through. And now, whilst I write this, sitting upon the quarterdeck, I have methinks one of the pleasantest scenes in the world before me. 'Tis a fine, clear day, and we are going away before the wind with an easy, pleasant gale. We have near fifteen sail of ships in sight, and I may say in company. On the left hand appears the coast of France at a distance, and on the right is the town and castle of Dover, with the green hills and chalky cliffs of England, to which we must now bid farewell. Albion, farewell!"

Fitful winds brought them on Wednesday to Spithead, where Denham and Franklin went ashore. Franklin, describing Portsmouth, commented on stories he had heard of a former Heuten-ant-governor. "It is a common maxim that without severe discipline 'tis impossible to govern the licentious rabble of soldiery. I own, indeed, that if a commander finds he has not those qualities in him that will make him beloved by his people, he ought by all means to make use of such methods as will make them fear him, since one or the other (or both) is absolutely necessary; but Alexander and Caesar, those renowned generals, received more faithful service, and performed greater actions, by means of the love their soldiers bore them, than they could possibly have done if, instead of being beloved and respected, they had been hated and feared by those they commanded."

From Cowes the ship was to sail early Friday morning, but the wind was adverse, and Franklin with other restless or curious passengers went ashore to see Newport, the "metropolis" of the Isle of Wight, and Carisbrooke Castle, "which King Charles the First was confined in." About Charles and his fate Franklin said nothing. His eyes were for living sights, "I think Newport is chiefly remarkable for oysters, which they send to London and other places, where they are very much esteemed, being thought the best in England. The oyster merchants fetch them, as I am informed, from other places, and lay them upon certain beds in the river (the water of which is it seems excellently adapted for that purpose) a-fattening; and when they have lain a suitable time they are taken up again, and made fit for sale."

Franklin noticed that the monuments on the island were all

^8 : BENJAMIN FRANKLIN

cut from soft stone and that the inscriptions are none of them legible. At the castle: "The floors are several of them of plaster of Paris, the art of making which, the woman told us, was now lost. . . . There are several breaches in the ruinous walls, which are never repaired (I suppose they are purposely neglected). . . . There is a well in the middle of the Coop which they called the bottomless well, because of its great depth; but it is now half filled up with stones and rubbish, and is covered with two or three loose planks; yet a stone, as we tried, is near a quarter of a minute in falling before you hear it strike. But the well that supplies the inhabitants at present with water is in the lower castle, and is thirty fathoms deep. They draw their water with a great wheel, and with a bucket that holds near a barrel. It makes a great sound if you speak in it, and echoed the flute which we played over it very sweetly."

The young realist was a moralist. When he was told of a former governor of the island who had seemed a saint and yet turned out to be a villain: "What surprised me was that the silly old fellow, the keeper of the castle, who remembered him governor, should have so true a notion of his character as I perceived he had. In short, I believe it is impossible for a man, though he has all the cunning of a devil, to live and die a villain, and yet conceal it so well as to carry the name of an honest fellow to his grave with him, but some one, by some accident or other, shall discover him. Truth and sincerity have a certain distinguishing native lustre about them which cannot be perfectly counterfeited; they are like fire and flame, that cannot be painted."

The young moralist reflected about everything, even about the game of draughts (checkers) which he played all that Friday afternoon after they had come back to the ship. "It is a game I much delight in; but it requires a clear head, and undisturbed; and the persons playing, if they would play well, ought not much to regard the consequence of the game, for that diverts and withdraws the attention of the mind from the game itself, and makes the player liable to make many false moves; and I will venture to lay it down for an infaUible rule, that if two persons equal in judgment play for a considerable sum, he that loves money most shall lose; his anxiety for the success of the game confounds him. Courage is almost as requisite for the good conduct of this game

PHILADELPHIA Joumeyman : ^p

as in a real battle; for if the player imagines himself opposed by one that is much his superior in skill, his mind is so intent on the defensive part that an advantage passes unobserved."

Saturday the ship got as far as Yarmouth, still on the Isle of Wight, and several passengers went ashore to dine. All but three of them sat drinking after dinner. The three, including Franklin, went further inland, headed a creek and came down on the other side, and at dark found themselves cut off from Yarmouth by the stream. "We were told that it was our best way to go straight down to the mouth of the creek, and that there was a ferry boy that would carry us over to the town. But when we came to the house the lazy whelp was in bed and refused to rise and put us over; upon which we went down to the water-side, with a design to take his boat and go over by ourselves. Wg found it very difficult to get the boat, it being fastened to a stake, and the tide risen near fifty yards beyond it; I stripped all to my shirt to wade up to it; but missing the causeway, which was under water, I got up to my middle in mud. At last I came to the stake; but, to my great disappointment, found she was locked and chained. I endeavoured to draw the staple with one of the thole-pins, but in vain; I tried to pull up the stake, but to no purpose; so that, after an hour's fatigue and trouble in the wet and mud, I was forced to return without the boat.

"We had no money in our pockets, and therefore began to conclude to pass the night in some haystack, though the wind blew very cold and very hard. In the midst of these troubles one of us recollected that he had a horse-shoe in his pocket, which he found in his walk, and asked me if I could not wrench the staple out with that. I took it, went, tried, and succeeded, and brought the boat ashore to them. Now we rejoiced and all got in, and, when I had dressed myself, we put off. But the worst of our troubles was to come yet; for, it being high water and the tide over all the banks, though it was moonlight we could not discern the channel of the creek; but, rowing heedlessly straight forward, when we were got about half-way over, we found ourselves aground on a mud bank; and, striving to row her off by putting our oars in the mud, we broke one and there stuck fast, not having four inches of water. We were now in the utmost perplexity, not knowing what in the world to do; we could not

60 : BENJAMIN FRANKLIN

tell whether the tide was rising or falling; but at length we plainly perceived it was ebb, and we could feel no deeper water within the reach of our oar.

"It was hard to lie in an open boat all night exposed to the wind and weather; but it was worse to think how foolish we should look in the morning, when the owner of the boat should catch us in that condition, where we must be exposed to the view of all the town. After we had strove and struggled for half an hour and more, we gave all over, and sat down with our hands before us, despairing to get off; for, if the tide had left us, we had been never the nearer; we must have sat in the boat, as the mud was too deep for us to walk ashore through it, being up to our necks. At last we bethought ourselves of some means of escaping, and two of us stripped and got out, and, thereby lightening the boat, we drew her upon our knees near fifty yards into deeper water; and then with much ado, having but one oar, we got safe ashore under the fort; and, having dressed ourselves and tied the man's boat, we went with great joy to the Queen's Head, where we left our companions, whom we found waiting for us, though it was very late. Our boat being gone on board, we were obliged to lie ashore all night; and thus ended our walk."

For six days the ship waited for favourable wind at Yarmouth or Cowes, and not until 5 August did they get away into the Channel. The next day: "In the afternoon I leaped overboard and swam round the ship to wash myself." On the 8th they saw the Lizard, and on the 9th took their leave of the land. Then for nine days there was nothing more remarkable than that "four dolphins followed the ship for some hours; we struck at them with the fizgig, but took none. . . .

'"''Friday, August I^.— . . . Yesterday, complaints being made

that Mr. G n, one of the passengers, had with a fraudulent

design marked the cards, a court of justice was called immediately, and he was brought to his trial in form. A Dutchman, who could speak no English, deposed by his interpreter that, when our mess was on shore at Cowes, the prisoner at the bar marked all the court cards on the back with a pen.

"I have sometimes observed that we are apt to fancy the person that cannot speak intelligibly to us, proportionably stupid in

PHILADELPHIA Joumeywan : 6i

understanding, and when we speak two or three words of English to a foreigner, it is louder than ordinary, as if we thought him deaf and that he had lost the use of his ears as well as his tongue. Something like this I imagine might be the case of Mr.

G n; he fancied the Dutchman could not see what he was

about, because he could not understand English, and therefore boldly did it before his face.

"The evidence was plain and positive; the prisoner could not deny the fact, but replied in his defence that the cards he marked were not those we commonly played with, but an imperfect pack, which he afterwards gave to the cabin boy. The attorney-general observed to the court that it was not likely he should take pains to mark the cards without some ill design, or some further intention than just to give them to the boy when he had done, who understood nothing at all of cards. But another evidence, being called, deposed that he saw the prisoner in the main-top one day, when he thought himself unobserved, marking a pack of cards on the backs, some with the print of a dirty thumb, others with the top of his finger, etc. Now, there being but two packs on board, and the prisoner having just confessed the marking of one, the court perceived the case was plain. In fine the jury brought him in guilty, and he was condemned to be carried up to the round-top, and made fast there in view of the ship's company during the space of three hours, that being the place where the act was committed, and to pay a fine of two bottles of brandy. But the prisoner resisting authority and refusing to submit to punishment, one of the sailors stepped aloft and let down a rope to us, which we with much struggling made fast about his middle, and hoisted him up into the air, sprawling, by main force. AVe let him hang, cursing and swearing, for near a quarter of an hour; but at length, he crying out 'Murder!' and looking black in the face, the rope being overtort about his middle, we thought proper to let him down again; and our mess have excommunicated him till he pays his fine, refusing either to play, eat, drink, or converse with him. . . .

"'Thursday, August 2j.—Our excommunicated shipmate thinking proper to comply with the sentence the court passed upon him, and expressing himself willing to pay the fine, we have this

62 : BENJAMIN FRANKLIN

morning received him into unity again. A4an is a sociable being, and it is, for aught I know, one of the worst punishments to be excluded from society. I have read abundance of fine things on the subject of solitude, and I know 'tis a common boast in the mouths of those that affect to be thought wise, that they are never less alone than when alone. I acknowledge solitude an agreeable refreshment to a busy mind; but were these thinking people obliged to be always alone, I am apt to think they would quickly find their very being insupportable to them. . . . One of the philosophers, I think it was Plato, used to say that he had rather be the veriest stupid block in nature than the possessor of all knowledge without some intelligent being to communicate it to.

"What I have said may in a measure account for some particulars in my present way of living here on board. Our company is in general very unsuitably mixed, to keep up the pleasure and spirit of conversation; and, if there are one or two pair of us that can sometimes entertain one another for half an hour agreeably, yet perhaps we are seldom in the humour for it together. I rise in the morning and read for an hour or two perhaps, and then reading grows tiresome. Want of exercise occasions want of appetite, so that eating and drinking afford but little pleasure. I tire myself with playing at draughts, then I go to cards; nay, there is no play so trifling or childish but we fly to it for entertainment. A contrary wind, I know not how, puts us all out of good humour; we grow sullen, silent, and reserved, and fret at each other upon every little occasion. 'Tis a common opinion among the ladies that if a man is illnatured he infallibly discovers it when he is in liquor. But I, who have known many instances to the contrary, will teach them a more effectual method to discover the natural temper and disposition of their humble servants. Let the ladies make one long sea voyage with them, and if they have the least spark of ill-nature in them and conceal it to the end of the voyage, I will forfeit all my pretensions to their favour."

For the rest of the voyage, as if he had learned whatever there was to know about his human companions. Franklin gave more attention in his journal to nature than to man.

''Tuesday, August 50.—Contrary wind still. This evening, the

PHILADELPHIA journeyman : 6^

moon being near full as she rose after eight o'clock, there appeared a rainbow in a western cloud, to windward of us. The first time I ever saw a rainbow in the night, caused by the moon. . . .

''Friday, Sept[eniber] 2.—This morning the wind changed; a little fair. We caught a couple of dolphins and fried them for dinner. They eat indifferent well. These fish make a glorious appearance in the water; their bodies are of a bright green, mixed with a silver colour, and their tails of a shining golden yellow; but all this vanishes presently after they are taken out of their element, and they change all over to a light grey. I observed that, cutting off pieces of a just-caught, living dolphin for baits, those pieces did not lose their lustre and fine colours when the dolphin died, but retained them perfectly. Everyone takes notice of that vulgar error of the painters, who always represent this fish monstrously crooked and deformed, when it is in reality as beautiful as any fish that swims. . . .

"'Wedyiesday, Sept[ei}iher] z^.—This afternoon, about two o'clock, it being fair weather and almost calm, as we sat playing draughts upon deck we were surprised with a sudden and unusual darkness of the sun, which, as we could perceive, was only covered with a small, thin cloud; when that was passed by we discovered that that glorious luminary laboured under a very great eclipse. At lease ten parts out of twelve of him were hid from our eyes, and we were apprehensive he would have been totally darkened. . . .

''Wednesday, Sept[ember] 2/.— This morning our steward was brought to the gears and whipped, for making an extravagant use of flour in the puddings, and for several other misdemeanours. It has been perfectly calm all this day, and very hot. I was determined to wash myself in the sea today, and should have done so had not the appearance of a shark, that mortal enemy to swimmers, deterred me; he seemed to be about five foot long, moves around the ship at some distance, in a slow, majestic manner, attended by near a dozen of those they call pilot fish, of different sizes; the largest of them is not so big as a small mackerel, and the smallest not bigger than my little finger. Two of these diminutive pilots keep just before his nose, and he

6^ : BENJAMIN FRANKLIN

seems to govern himself in his motions by their direction; while the rest surround him on every side indifferently. A shark is never seen without a retinue of these, who are his purveyors, discovering and distinguishing his prey for him; while he in turn gratefully protects them from the ravenous, hungry dolphin.

''Friday, September 25.—This morning we spied a sail to windward on us about two leagues. We showed our jack upon the ensign-staff and shortened sail for them till about noon, when she came up to us. She was a snow [brig] from Dublin, bound for New York, having upwards of fifty servants on board of both sexes; they all appeared upon deck, and seemed very much pleased at the sight of us. There is something strangely cheering to the spirits in the meeting of a ship at sea, containing a society of creatures of the same species and in the same circumstances with ourselves, after we had been long separated and excommunicated as it were from the rest of mankind. My heart fluttered in my breast with joy, when I saw so many human countenances, and I could scarce refrain from that kind of laughter which proceeds from some degree of inward pleasure. When we have been for a considerable time tossing on the vast waters, far from the sight of any land or ships, or any mortal creature but ourselves (except a few fish and sea birds), the whole world, for aught we know, may be under a second deluge, and we, like Noah and his company in the ark, the only surviving remnant of the human race. . . .

"I find our messmates in a better humour and more pleased with their present condition than they have been since they came out; which I take to proceed from the contemplation of the miserable circumstances of the passengers on board our neighbour, and making the comparison. We reckon ourselves in a kind of paradise, when we consider how they live, confined and stifled up with such a lousy, stinking rabble, in this hot sultry latitude."

The Berkshire, with only twenty-one on board, and the crowded snow "ran on very lovingly together" for a week, except when the wind separated them at night, and twice the snow's captain came on board the ship. On 25 September: "All our discourse now is of Philadelphia, and we begin to fancy our-

PHILADELPHIA Joumeymafi : 6$

selves ashore already." On the 27th: "I have laid a bowl of punch that we are in Philadelphia next Saturday se'ennight; for we reckon ourselves not above one hundred and fifty leagues from land." (Franklin was too hopeful by three days.)

''''Wednesday, Sept[eviber] zS.—VJt had very variable winds and weather last night, accompanied with abundance of rain; and now the wind is come about westerly again, but we must bear it with patience. This afternoon we took up several branches of gulf-weed (with which the sea is spread all over, from the Western Isles to the coast of America); but one of these branches had something peculiar in it. In common with the rest, it had a leaf about three-quarters of an inch long, indented like a saw, and a small yellow berry, filled with nothing but wind; besides which it bore a fruit of the animal kind, very surprising to see. It was a small shell-fish like a heart, the stalk by which it proceeded from the branch being partly of a gristly kind. Upon this one branch of the weed there were near forty of these vegetable animals; the smallest of them, near the end, containing a substance somewhat like an oyster, but the larger were visibly animated, opening their shells every moment, and thrusting out a set of uniformed claws, not unlike those of a crab; but the inner part was still a kind of soft jelly. Observing the weed more narrowly, I spied a very small crab crawling among it, about as big as the head of a ten-penny nail, and of a yellowish colour, like the weed itself. This gave me some reason to think that he was a native of the branch; that he had not long since been in the same condition with the rest of those little embryos that appeared in the shells, this being the method of their generation; and that, consequently, all the rest of this odd kind of fruit might be crabs in due time. To strengthen my conjecture I have resolved to keep the weed in salt water, renewing it every day till we come on shore, by this experiment to see whether any more crabs will be produced or not in this manner. . . . The various changes that silkworms, butterflies, and several other insects go through, make such alterations and metamorphoses not improbable.

""Thursday, Sept[emher] 25).—Upon shifting the water in which I had put the weed yesterday, I found another crab, much smaller than the former, who seemed to have newly left his habi-

66 : BENJAMIN FRANKLIN

tation. But the weed begins to wither, and the rest of the embryos are dead. This new-comer fully convinces me that at least this sort of crabs are generated in this manner.

''Friday, Sept[ember] 50.—I sat up last night to observe an eclipse of the moon, which the calendar, calculated for London, informed us would happen at five o'clock in the morning. . . , It began with us about eleven last night, and continued till near two this morning, darkening her body about six digits, or one half; the middle of it being about half an hour after twelve, by which we may discover that we are in a meridian of about four hours and a half from London, or 67 V2 degrees of longitude, and consequently have not much above one hundred leagues to run. This is the second eclipse we have had within these fifteen days."

The bored shipmates had again something to talk about: their distance from Philadelphia. On 2 October: "I cannot help fancying the water is changed a little, as is usual when a ship comes within soundings, but 'tis probable I am mistaken; for there is but one besides myself of my opinion, and we are very apt to believe what we wish to be true." The next day: "The water is now very visibly changed to the eyes of all except the captain and mate, and they will by no means allow it; I suppose because they did not see it first. . . .

''Tuesday, October ^.—Last night we struck a dolphin, and this morning we found a flying-fish dead under the windlass. He is about the bigness of a small mackerel, a sharp head, a small mouth, and a tail forked somewhat like a dolphin, but the lowest branch much larger and longer than the other, and tinged with yellow. His back and sides of a darkish blue, his belly white, and his skin very thick. His wings are of a finny substance, about a span long, reaching when close to his body from an inch below his gills to an inch above his tail. When they fly it is straight forward (for they cannot readily turn) a yard or two above the water; and perhaps fifty yards is the furthest before they dip into the water again, for they cannot support themselves in the air any longer than while their wings continue wet. These flying-fish are the common prey of the dolphin, who is their mortal enemy. When he pur-sues them, they rise and fly; and he keeps close under them till they drop, and then snaps them up immediately. They generally fly in flocks, four or five, or perhaps a

dozen together, and a dolphin is seldom caught without one or more in his belly."

Now Franklin's curiosity was all for signs that the ship was nearing home. On 4 October: "This afternoon we have seen abundance of grampuses, which are seldom far from land; but towards evening we had a more evident token, to wit, a little tired bird, something like a lark, came on board us, who certainly is an American, and 'tis likely was ashore this day." On 5 October: "This morning we saw a heron, who had lodged aboard last night. 'Tis a long-legged, long-necked bird, having, as they say, but one gut. They live upon fish, and will swallow a Hving eel thrice, sometimes, before it will remain in their body." On 7 October (gloomily): "For my part I know not what to think of it; we have run all this day at a great rate, and now night is come on we have no soundings. Sure the American continent is not all sunk under water since we left it." But on 9 October: "After dinner one of our mess went aloft to look out, and presently pronounced the long wished-for sound: LAND! LAND! In less than an hour we could descry it from the deck, appearing like tufts of trees. I could not discern it so soon as the rest; my eyes were dimmed with the suffusion of two small drops of joy.

""Monday, October /o.—This morning we stood in again for land; and we that had been here before all agreed that it was Cape Henlopen; about noon we were come very near, and to our great joy saw the pilot-boat come off to us, which was exceeding welcome. He brought on board about a peck of apples with him; they seemed the most delicious I ever tasted in my life; the salt provisions we had been used to gave them a relish. We had extraordinary fair wind all the afternoon, and ran above a hundred miles up the Delaware before ten at night. The country appears very pleasant to the eye, being covered with woods, except here and there a house and plantation. We cast anchor when the tide turned, about two miles below New Castle, and there lay till the morning tide.

''^Tuesday, October //.—This morning we weighed anchor with a gentle breeze and passed by New Castle, whence they hailed us and bade us welcome. It is extreme fine weather. The sun enlivens our stiff limbs with his glorious rays of warmth and brightness. The sky looks gay, with here and there a silver cloud.

68 : BENJAMIN FRANKLIN

The fresh breezes from the woods refresh us; the immediate prospect of hberty, after so long and irksome confinement, ravishes us. In short, all things conspire to make this the most joyful day I ever knew. As we passed by Chester, some of the company went on shore, impatient once more to tread on terra firina, and designing for Philadelphia by land. Four of us remained on board, not caring for the fatigue of travel when we knew the voyage had much weakened us. About eight at night, the wind failing us, we cast anchor at Redbank, six miles from Philadelphia, and thought we must be obliged to lie on board that night; but some young Philadelphians happening to be out upon their pleasure in a boat, they came on board, and offered to take us up with them; we accepted of their kind proposal, and about ten o'clock landed at Philadelphia, heartily congratulating each other upon our having happily completed so tedious and dangerous a voyage. Thank God!"

Master

DURING the voyage home Frankhn drew up a plan by which he was to regulate his future conduct, and which he says he followed, on the whole, "quite through to old age." The original plan is missing from his journal. What resolutions he had made must now be guessed at, though they were possibly the ones printed long afterwards from a manuscript now apparently lost. "Those who write of the art of poetry teach us that if we would write what may be worth reading we ought always, before we begin, to form a regular plan and design of our piece; otherwise we shall be in danger of incongruity. I am apt to think it is the same as to life. I have never fixed a regular design as to life, by which means it has been a confused variety of different scenes. I am now entering upon a new one; let me therefore make some resolutions, and form some scheme of action, that henceforth I may live in all respects like a rational creature, i. It is necessary for me to be extremely frugal for some time, till I have paid what I owe. 2. To endeavour to speak truth in every instance, to give nobody expectations that are not likely to be answered, but aim at sincerity in every word and action: the most amiable excellence in a rational being. 3. To apply myself industriously to whatever business I take in hand, and not divert my mind from my business by any foolish project of growing suddenly rich; for industry and patience are the surest means of plenty. 4. I resolve

69

70 : BENJAMIN FRANKLIN

to speak ill of no man whatever, not even in a matter of truth; but rather by some means excuse the faults I hear charged upon others, and upon proper occasions speak all the good I know of everybody."^

Franklin's life for this first year in Philadelphia was not as he had planned. For four or five months he was busy in his new employment. Denham set up a general store in Water Street with the stock which he had brought from England, taught Franklin to keep accounts and to sell goods, and gave him affectionate counsel. They lived together like father and son. Franklin, who missed his own father, celebrated his twenty-first birthday by a high-sounding letter to his youngest and favourite sister Jane, then not yet fifteen but to be married the following July. He had heard, he said, that she had become a beauty and wanted to send her a present. "I had almost determined on a tea table; but when I considered that the character of a good housewife was far preferable to that of being only a pretty gentlewoman, I concluded to send you a spinning-wheel." He sent a moral reflection too. "Sister, farewell, and remember that modesty, as it makes the most homely virgin amiable and charming, so the want of it in-falhbly renders the most perfect beauty disagreeable and odious. But when that brightest of female virtues shines among other perfections of body and mind in the same person, it makes the woman more lovely than an angel. Excuse this freedom, and use the same with me."

Within a month after this letter both Denham and Franklin were taken seriously ill. "My distemper was a pleurisy, which very nearly carried me off. I suffered a great deal, gave up the point in my own mind, and was rather disappointed when I found myself recovering, regretting, in some degree, that I must now some time or other have all that disagreeable work to do over again."- Denham's ledger^ shows that Franklin must have come home nearly penniless, for during his twenty weeks' work he had to be advanced cash and goods to the amount of three shillings and five-pence more than the six pounds which his wages came to. Denham, dying after a long sickness, forgave Franklin the unpaid balance and the ten pounds' passage money —or as Franklin says: "he left me a small legacy in a noncupa-

PHILADELPHIA MaStCT : JI

tive will." The journeyman who had left his trade went back to it.

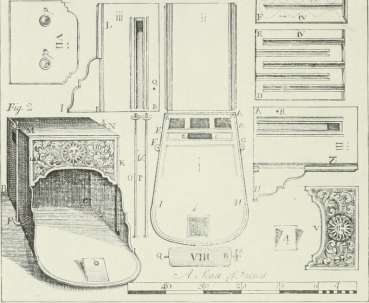

Once more a printer, working for Keimer again, Franklin now lived only partly as he had before in Philadelphia. He had no secret patron. Keith had been removed from his post as governor and was shortly to leave the province. "I met him walking the streets as a common citizen. He seemed a little ashamed at seeing me, but passed without saying anything." Deborah Read, with her one letter from London, had lost hope of Franklin and had married a potter named Rogers, a good workman but a worthless man, with whom she had never been happy and from whom she was soon parted, after she heard he already had a wife. Franklin renewed his friendship with his former companions in poetry, but Watson died and Osborne went to the West Indies, At the printing-house Franklin was more than foreman. It did not take him long to understand that Keimer had hired him at high wages to be, in effect, teacher to the "raw, cheap hands" at work there, and to be dismissed when they had learned their trade. Franklin was as cheerful as he was skilful with his random crew. Three of them were young Pennsylvania farmers who had ambitiously come to Philadelphia: David Harry who later became Franklin's competitor, Hugh Meredith who became his partner, and Stephen Potts, his lifelong friend. Two of them were indentured servants: John, a wild Irishman who ran away, and George Webb, who had deserted Oxford after a year, gone to London to become an actor, spent all his money, and bound himself for his passage to be a servant in America, where Keimer had bought his time for four years from the captain of the ship. Franklin, besides instructing and disciplining them, took other responsibilities. "There was no letter-founder in America; I had seen types cast at James's in London, but without much attention to the manner; however, I now contrived a mould, made use of the letters we had as puncheons, struck the matrices in lead, and thus supplied in a pretty tolerable way all deficiencies. I also engraved several things on occasion; I made the ink; I was warehouseman, and everything."^

Serviceable as Franklin was, Keimer, short-tempered, shortsighted, after six months began looking for an excuse to let his

7-2 : BENJAMIN FRANKLIN

foreman go, now that the shop had been put in order. "A trifle snapped our connexions; for, a great noise happening near the courthouse, I put my head out of the window to see what was the matter. Keimer, being in the street, looked up and saw me, called out to me in a loud voice and angry tone to mind my business, adding some reproachful words that nettled me the more for their publicity, all the neighbours who were looking out on the same occasion being witnesses how I was treated."^ Keimer came indoors, the quarrel grew furious, and Franklin, waiving the quarter's notice that was due him, caught up his hat and left without the rest of his belongings.

Hugh Meredith brought them to Franklin that evening, and they talked over what was to be done. Franklin had begun to think of going back to Boston. Meredith, anxious not to lose so good and able a friend, urged him to stay in Philadelphia, wait for Keimer's certain failure, and succeed him. Though Franklin had no capital, iMeredith's father had a high opinion of the young foreman, and might set the two up in business as equal partners, Franklin's skill counting for as much as Meredith's money. The father was just then in town and approved of the scheme, partly because his son had stopped drinking under his friend's influence Frankhn furnished the elder Meredith an inventory of what would be needed, and the order was sent off to London. It would of course be several months before the types and press could arrive. For a few days Franklin was idle. Then Keimer, "on a prospect of being employed to print some paper money in New Jersey, which would require cuts and various types that I only could supply, and apprehending Bradford might engage me and get the job from him,"*^ civilly, if interestedly, asked Franklin to forget the quarrel and return to work. jMeredith strongly urged this, for his time with Keimer would not be up till the following spring, and he felt the need of more instruction. Franklin yielded in his friendly manner, which was both natural and astute. He contrived the first copperplate press in the country, and cut ornaments for the bills. With Keimer he went to Burlington, where he did the printing to the full satisfaction of the Assembly.

Keimer made money enough in Burlington to keep him going for a year or so more. Franklin made friends for a lifetime. The

PHILADELPHIA MaStCT : J ^

members of the committee who watched the printing to see that no unauthorized bills were struck off liked Franklin and felt his irresistible young charm. The\' asked him, not Keimer, to their houses and introduced him to others. At the end of three months he was on the best of terms with the secretary and the surveyor-general of the province and several members of the legislature. One shrewd old man, who knew nothing of Franklin's plans, prophesied that he would sooner or later take Keimer's business away from him and make a fortune. Not long after the printers were back in Philadelphia, early in 1728, the new equipment came. Meredith and Franklin, without telling Keimer they were to be his rivals, settled with him and left with his consent. They took a house in lower Market Street for twenty-four pounds a year, let a part of it to Thomas Godfrey, a mathematical glazier with whose family they ^vere to board, and opened the new shop. Their first customer was a farmer M^ho had been wandering through the streets looking for a printer and had been brought in by one of their friends. "This countryman's five shillings, being our first fruits, and coming so seasonably, gave me more pleasure than any crown I have since earned."'

II

No single thread of narrative can give a true account of Franklin's life during the years 1726-32, for he was leading three lives and—most of the time—something of a stealthy fourth, each distinct enough to call for a separate record and yet all of them closely involved in his total nature. There was his public life, beginning with his friendships in the club he organized in 1727, and continuing with larger and larger affairs as long as he lived. There was his inner life, which was at first much taken up with reflections on his own behaviour, and, after he had more or less settled that in his mind and habit, grew to an embracing curiosity about the whole moral and physical world. There was his life as workman—already told—and business man, which greatly occupied him and was to occupy him until, after twenty vears in Philadelphia, he was able to retire from an activity he had never

74 : BENJAMIN FRANKLIN

valued for itself. In time all three were to be fused in the spacious character of a sage in action, but in 1726-32 they were still distinct if not discrepant.

In business Franklin was extremely alert to the main chance, adaptable, resolute, crafty though not petty, and ruthless on occasion. But he had too ranging a mind to be taken up with his private concerns alone, and he genuinely desired the pubhc welfare. Having neither wealth nor influence, he began where he could, using the tools he had. In the fall of 1727, about the time of his trouble with Keimer, he brought together the group called the Junto. Three besides Franklin—Hugh Meredith, Stephen Potts, and George Webb—were from Keimer's shop. Meredith was "a Welsh Pennsylvanian, thirty years of age, bred to country work; honest, sensible, had a great deal of solid observation, was something of a reader but given to drink. . . . Potts, a young countryman of full age, bred to the same, of uncommon natural parts, and great wit and humour, but a little idle. . . . Webb, an Oxford scholar . . . lively, witty, good-natured, and a pleasant companion, but idle, thoughtless, and imprudent to the last degree."^

With these were joined: "Joseph Breintnal, a copier of deeds for the scriveners, a good-natured, friendly, middle-aged man, a great lover of poetry, reading all he could meet with and writing some that was tolerable; very ingenious in many little knick-knackeries and of sensible conversation. Thomas Godfrey, a self-taught mathematician, great in his way, and afterward inventor of what is now called Hadley's quadrant. But he knew little out of his way, and was not a pleasing companion; as, like most great mathematicians I have met with, he expected universal precision in everything said, and was for ever denying or distinguishing upon trifles, to the disturbance of all conversation. He soon left us. Nicholas Scull, a surveyor, afterwards surveyor-general, who loved books and sometimes made a few verses. William Parsons, bred a shoemaker, but, loving reading, had acquired a considerable share of mathematics, which he first studied with a view to astrology, but he afterwards laughed at it. He also became a surveyor-general. William Maugridge, a joiner, a most exquisite mechanic, and a solid, sensible man. . . . Robert Grace, a young gentleman of some fortune, generous, lively, and witty; a lover of

punning and of his friends. And AVilliam Coleman, then a merchant's clerk, about my age, who had the coolest, clearest head, the best heart, and the exactest morals of almost any man I ever met with. He became afterwards a merchant of great note, and one of our provincial judges."'*

These solid, sensible, good-natured, ingenious—and inconspicuous—men were friends with whom Frankhn already liked to talk, and it was a kind of economy to meet with them all at once at a tavern every Friday evening. There can be no doubt whose club it was. Franklin gave it form and direction. Many of the topics discussed were raised by him. The Junto was his benevolent lobby for the benefit of Philadelphia, and now and then for the advantage of Benjamin Franklin.

Somewhat unexpectedly, he seems to have borrowed the scheme of the Junto in part from Cotton Mather, who in Boston had originated neighbourhood benefit societies, one for every church, and had belonged to twenty of them. Mather had drawn up a set of ten questions to be read at each meeting, "with due pauses," as a guide to discussion.^"^ Franklin, in his Rules for the Junto adopted in 1728, followed Mather. Some of the questions were much the same. Mather had asked: "Is there any matter to be humbly moved unto the legislative power, to be enacted into a law for public benefit?" Franklin asked: "Have you lately observed any defect in the law s of your country of which it would be proper to move the legislature for an amendment? Or do you know of any beneficial law that is wanting?" Mather: "Is there any particular person whose disorderly behaviour may be so scandalous and so notorious that we may do well to send unto the said person our charitable admonitions?" Franklin: "Do you know of a fellow-citizen who has lately done a worthy action, deserving praise or imitation; or who has lately committed an error proper for us to be warned against and avoid?" Mather: "Does there appear any instance of oppression or fraudulence in the dealings of any sort of people that may call for our essays to get it rectified?" Franklin: "Have you lately observed any encroachment on the just liberties of the people?" But Franklin has nothing like Mather's: "Can any further methods be devised that ignorance and wickedness may be chased from our people in general, and that household piety in particular may flourish

'j6 : BENJAMIN FRANKLIN

among them?" And Mather has nothing hke most of FrankUn's twenty-four humane, secular, practical inquiries:

"i. Have you met with anything in the author you last read, remarkable or suitable to be communicated to the Junto, particularly in history, morality, poetry, physic, travels, mechanic arts, or other parts of knowledge? 2. What new story have you lately heard agreeable for telling in conversation? 3. Hath any citizen in your knowledge failed in his business lately, and what have you heard of the cause? 4. Have you lately heard of any citizen's thriving well, and by what means? ... 7. What unhappy effects of intemperance have you lately observed or heard; of imprudence, of passion, or of any other vice or folly? 8. What happy effects of temperance, of prudence, of moderation, or of any other virtue? 9. Have you or any of your acquaintance been lately sick or wounded? If so, what remedies were used, and what were their effects? 10. Whom do you know that are shortly going voyages or journeys, if one should have occasion to send by them? ... 12. Hath any deserving stranger arrived in town since last meeting that you have heard of? And what have you heard or observed of his character or merits? And whether, think you, it lies in the power of the Junto to oblige him, or encourage him as he deserves? 13. Do you know of any deserving young beginner lately set up, whom it lies in the power of the Junto any way to encourage? ... 16. Hath anybody attacked your reputation lately? And what can the Junto do towards securing it? 17. Is there any man whose friendship you want, and which the Junto, or any of them, can procure for you 18. Have you lately heard any member's character attacked, and how have you defended it? 19. Hath any man injured you, from whom it is in the power of the Junto to procure redress? 20. In what manner can the Junto, or any of them, assist you in any of your honourable designs? . . .""

These questions were the Junto's weekly ritual. The members met first in a tavern, later in a room hired in a house belonging to Grace. Between questions there were, as in Boston, due pauses— in Philadelphia long enough to drink a glass of wine. The rules further required that "every member, in his turn, should produce one or more queries on any point of morals, politics, or natural philosophy, to be discussed by the company; and once in three

PHILADELPHIA Master : 77

months produce and read an essay of his own writing, on any subject he pleased. Our debates were to be under the direction of a president, and to be conducted in the sincere spirit of inquiry after truth, without fondness for dispute or desire of victory; and, to prevent warmth, all expressions of positiveness in opinions, or direct contradiction, were after some time made contraband, and prohibited under small pecuniary penalties."^"

Franklin in his own queries asked the Junto things he was asking himself. "How shall we judge of the goodness of a writing? Or what qualities should a writing have to be good and perfect in its kind?" (He wrote out his own answer, and summed up: "It should be smooth, clear, and short.") "Can a man arrive at perfection in this life, as some believe, or is it impossible, as others believe?" "Wherein consists the happiness of a rational creature?" "What is wisdom?" ("The knowledge of what will be best for us on all occasions, and the best ways of attaining it.") "Is any man wise at all times and in all things?" ("No, but some are more frequently wise than others.") "Whether those meats and drinks are not the best that contain nothing in their natural taste, nor have anything added by art, so pleasing as to induce us to eat or drink when we are not thirsty or hungry, or after thirst and hunger are satisfied; water, for instance, for drink, and bread or the like for meat?" "Is there any difference between knowledge and prudence? If there is any, which of the two is most eligible?" "Is it justifiable to put private men to death, for the sake of public safety or tranquillity, who have committed no crime? As, in the case of the plague, to stop infection; or as in the case of the Welshmen here executed?" "If the sovereign power attempts to deprive a subject of his right (or, which is the same thing, of what he thinks his right), is it justifiable in him to resist, if he is able?" "Which is best: to make a friend of a wise and good man that is poor or of a rich man that is neither wise nor good?" "Does it not, in a general way, require great study and intense application for a poor man to become rich and powerful, if he would do it without the forfeiture of honesty?" "Does it not require as much pains, study, and application to become truly wise and strictly virtuous as to become rich?" "Whence comes the dew that stands on the outside of a tankard that has cold water in it in the summer time? "^^

'j8 : BENJAMIN FRANKLIN

Many young men have organized clubs for talk and friendship, but only Franklin ever kept one alive for thirty years. He did not lose interest as most young men do, or tire of leadership. The Junto was his life enlarged and extended. It was convivial as well as philosophical. Once a month in the pleasant seasons the debaters met across the river for outdoor exercise. Once a year they had an anniversary dinner, with songs and healths. The Junto was practical as well as convivial. Perhaps, in the long run, the help the members gave each other had as much to do as anything with making it last. It was a secret brotherhood. New members had to stand up with their hands on their breasts and say they loved mankind in general and truth for truth's sake. But in the ritual questions many of the issues were more immediate. Strangers in Philadelphia were to be welcomed if they deserved it, young beginners in trade or business encouraged, reputations defended, friendships furthered, grievances redressed, useful information exchanged. Franklin himself was benefited. Breintnal brought the new printing-house its first large order. Grace and Coleman lent Franklin money to buy Meredith out. The Junto, commonly known at first as the Leather Apron, became the club of young, poor, enterprising men, as distinguished from the Merchants' Every Night, which was for the respectable and established, and the Bachelors, who were gay and suspected of being wicked. (Grace was a member of the Bachelors, and Webb, who wrote a poem called Batchelors-Hall which Franklin published.)

In time the Junto had so many applications for membership that it was at a loss to know how to limit itself to the twelve originally planned. Franklin, who preferred the convenient apostolic number, suggested that the Junto be kept as it was and that each member organize a subordinate club, "with the same rules respecting queries, etc., and without informing them of the connexion with the Junto. The advantages proposed were the improvement of so many more young citizens by the use of our institutions; our better acquaintance with the general sentiments of the inhabitants on any occasion, as the Junto member might propose what queries we should desire, and was to report to the Junto what passed in his separate club; the promotion of our particular interests in business by more extensive recommendation, and the increase of our influence in public affairs, and our power

PHILADELPHIA Master : jp

of doing good by spreading through the several clubs the sentiments of the Junto."^^ Only five or six of these subordinate clubs were founded.

The benevolent imperialism of the Junto did not go beyond these little clubs of artisans and tradesmen in Philadelphia, but Franklin for a few enthusiastic months had world-wide schemes. On 19 May 173 i, about the time he became a Mason, he set down, in the library of the Junto which was also the room where the club held its meetings, his observations on his reading of history. The affairs of the world, he had observed, are carried on by parties. These parties act in their own interest or what they think their interest. Their different interests cause natural confusion. Within each party each man has his own private interest. As soon as a party has gained its general point, each man puts forth his special claim, and the party comes to confusion within itself. Few men act for the good of their country except when they can believe that their country's good is also theirs. Fewer men still act for the good of mankind. Consequently: "There seems to me at present to be great occasion for raising a United Party for Virtue, by forming the virtuous and good men of all nations into a regular body, to be governed by suitable good and wise rules, which good and wise men may probably be more unanimous in their obedience to, than common people are to common laws."^^

The new sect was, much like the Junto, to be begun and spread by young single men joined in a secret society, each of whom should find other worthy members. "The members should engage to afford their advice, support, and assistance to each other in promoting one another's interests, business, and advancement in life. . . . For distinction, we should be called the Society of the Free and Easy: free, as being, by the general habit and practice of the virtues, free from the dominion of vice; and particularly, by the practice of industrv and frugality, free from debt, which exposes a man to confinement and a species of slavery to his creditors."^'' Franklin was himself to write a kind of gospel for these free and easy saints, a book to be called The Art of Virtue which would not merely exhort to goodness but would show the precise means of achieving it. Almost thirty years later he was still hoping to write the book, which he told Lord Kames

80 : BENJAMIN FRANKLIN

would be "adapted for universal use."^^ About his sect he did nothing but propose it to two young men who felt his enthusiasm. Then pressing matters intervened, and the Party for Virtue had to wait. Yet at eighty-two Franklin could say: "I am still of opinion that it was a practicable scheme, and might have been very useful, by forming a great number of good citizens; and I was not discouraged by the seeming magnitude of the undertaking, as I have always thought that one man of tolerable abilities may work great changes and accomplish great affairs among mankind, if he first forms a good plan and . . . makes the execution of that same plan his sole study and business."^^

III

Remembering FrankUn when he was old and canny, men forget that he was once young and passionate, romantic about the schemes which he realistically carried out, troubled by the conflict of many ideas in his fruitful mind, and ardently cherishing those he thought true and good. In London he had justified his looser impulses by arguing, against Wollaston, that men are machines driven by necessity and that there are no virtues and no vices in nature. But on his voyage home and during his first year or two in Philadelphia he decided that this argument was at fault. The freethinkers he had known best—Collins, Keith, Ralph—had all injured him, and he while a freethinker had behaved badly to his brother James, to Deborah Read, to Ralph's milliner, and to Vernon. There were in practice, perhaps in nature itself, such things as right and wrong. "Revelation had indeed no weight with me, as such; but I entertained an opinion that, though certain actions might not be bad because they were forbidden by it, or good because it commanded them, yet probably these actions might be forbidden because they were bad for us, or commanded because they were beneficial to us, in their own natures, all the circumstances of things considered."^^ His mind was too free to let him retreat to any contemporary sect, and he remained a deist. But neither was he able to be satisfied with a dry and niggling rationalism. Like Wollaston, he seems to have felt the need of some kind of ritual of worship. On 20 No-

PHILADELPHIA Master : 81

vember 1728, the year Franklin formulated the Junto's rules, he settled upon his Articles of Belief and Acts of Religion^^ which served as his creed—though he later simplified that—and his private religious ceremony.

Believing that there is one Supreme Being, "Author and Father of the Gods themselves," he still held in 1728, again with Wol-laston, that there are many lesser Gods, each in his system like a sun. To the God of his own system Franklin raised his "praise and adoration. ... I conceive for many reasons that He is a good Being, and as I should be happy to have so wise, good, and powerful a Being my friend, let me consider in what manner I shall make myself most acceptable to Him. Next to the praise resulting from and due to His wisdom, I believe He is pleased and delights in the happiness of those He has created; and since without virtue man can have no happiness in this world, I firmly believe He delights to see me virtuous, because He is pleased when He sees me happy. And since He has created many things which seem purely designed for the delight of man, I believe He is not offended when He sees his children solace themselves in any manner of pleasant exercises and innocent delights; and I think no pleasure innocent that is to man hurtful. I love Him therefore for His Goodness, and I adore Him for His Wisdom."

After this statement of First Principles, the form of Adoration. "Being mindful that before I address the Deity my soul ought to be calm and serene, free from passion and perturbation, or otherwise elevated with rational joy and pleasure, I ought to use a countenance that expresses a filial respect, mixed with a kind of smiling that signifies inward joy and satisfaction and admiration. . . . O Creator, O Father! I believe that Thou art good and that Thou art pleased with the pleasure of Thy children.—Praised be Thy name for ever. By Thy power hast Thou made the glorious sun, with his attending worlds; from the energy of Thy mighty will they first received their prodigious motion, and by Thy wisdom hast Thou prescribed the wondrous laws by which they move.—Praised be Thy name for ever. . . . Thou abhorrest in Thy creatures treachery, deceit, malice, revenge, intemperance, and every other hurtful vice; but Thou art a lover of justice and sincerity, of friendship and benevolence, and every virtue. Thou art my friend, my father, and my benefactor.—Praised

82 : BENJAMIN FRANKLIN

be Thy name, O God, for ever! Amen!" The Adoration concluded with "Milton's Hymn to the Creator" from Paradise Lost-^ and "the reading of some book, or part of a book, discoursing on and exciting to moral virtue."

Then the Petition and Thanks which completely reveal what the inner Franklin valued and desired.

"That I may be preserved from atheism and infidelity, impiety and profaneness, and in my addresses to Thee carefully avoid irreverence and ostentation, formality and odious hypocrisy,— Help me, O Father!

"That I may be loyal to my prince and faithful to my country, careful for its good, valiant in its defence, and obedient to its laws, abhorring treason as much as tyranny,—Help me, O Father!

"That I may to those above me be dutiful, humble, and submissive; avoiding pride, disrespect, and contumacy,—Help me, O Father!

"That I may to those below me be gracious, condescending, and forgiving, using clemency, protecting innocent distress, avoiding cruelty, harshness, and oppression, insolence, and unreasonable severity,—Help me, O Father!

"That I may refrain from censure, calumny, and detraction; that I may avoid and abhor deceit and envy, fraud, flattery, and hatred, malice, lying, and ingratitude,—Help me, O Father!

"That I may be sincere in friendship, faithful in trust, and impartial in judgment, watchful against pride and against anger (that momentary madness),—Help me, O Father!

"That I may be just in all my dealings, temperate in my pleasures, full of candour and ingenuity, humanity, and benevolence, —Help me, O Father!

"That I may be grateful to my benefactors, and generous to my friends, exercising charity and liberality to the poor and pity to the miserable,—Help me, O Father!

"That I may avoid avarice and ambition, jealousy and intemperance, falsehood, luxury, and lasciviousness,—Help me, O Father!

"That I may possess integrity and evenness of mind, resolution in difficulties, and fortitude under affliction; that I may be punctual in performing my promises, peaceable and prudent in my behaviour,—Help me, O Father!

"That I may have tenderness for the weak and reverent respect for the ancient; that I ma\' be kind to my neighbours, good-natured to my companions, and hospitable to strangers,—Help me, O Father!

"That I may be averse to talebearing, backbiting, detraction, slander and craft and overreaching, abhor extortion, perjury, and every kind of wickedness,—Help me, O Father!

"That I may be honest and open-hearted, gentle, merciful, and good, cheerful in spirit, rejoicing in the good of others,—Help me, O Father!

"That I may have a constant regard to honour and probity, that I may possess a perfect innocence and a good conscience, and at length become truly virtuous and magnanimous,—Help me, good God; help me, O Father!

"And forasmuch as ingratitude is one of the most odious of vices, let me be not unmindful gratefully to ackno\\'ledge the favours I receive from Heaven. . . .

"For peace and liberty, for food and raiment, for corn and wine and milk, and every kind of healthful nourishment,—Good God, I thank Thee!

"For the common benefits of air and light; for useful fire and delicious water,—Good God, I thank Thee!

"For knowledge and literature and every useful art, for my friends and their prosperity, and for the fewness of my enemies, —Good God, I thank Thee!

"For all Thy innumerable benefits; for life and reason and the use of speech; for health and joy and every pleasant hour,—My good God, I thank Thee!"

Though Franklin before he was twenty-three had so wide and serene a view of human behaviour, he had not yet resolved in himself the conflict between his instinct toward pleasure and his faith in reasonable virtue. He argued the matter out, some time in 1730, in two Socratic dialogues—suggested by The Moralists in Shaftesbury's Characteristics—\\\\\c\\ he read before the Junto and published in his newspaper.'- The speakers were Philocles and Horatio, really two dramatic halves of Franklin. Misfortune had sent Horatio, the man of pleasure, to philosophy for relief, and Philocles, the man of reason, told his friend that he had given more for pleasure than it was worth.

84' '■ BENJAMIN FRANKLIN

''Hor[atio]. That depends all upon opinion. Who shall judge what the pleasure is worth? Supposing a pleasing form of the fair kind strikes me so much that I can enjoy nothing without the enjoyment of that one object. Or, that pleasure in general is so favourite a mistress that I will take her as men do their wives, for better or worse; mind no consequences, nor regarding what's to come. Why should I not do it?

'Thil[ocles]. Suppose, Horatio, that a friend of yours entered into the world about two-and-twenty, with a healthful vigorous body, and a fair plentiful estate of about five hundred pounds a year; and yet, before he had reached thirty, should, by following his pleasures and not, as you say, duly regarding consequences, have run out of his estate and disabled his body to that degree that he had neither the means nor capacity of enjoyment left, nor anything else to do but wisely shoot himself through the head to be at rest; what would you say to this unfortunate man's conduct? . . . Does that miserable son of pleasure appear as reasonable and lovely a being in your eyes as the man who, by prudently and rightly gratifying his natural passions, had preserved his body in full health, and his estate entire, and enjoyed both to a good old age, and then died with a thankful heart for the good things he had received . . . ? Say, Horatio, are these men equally wise and happy? And is everything to be measured by mere fancy and opinion, without considering whether that fancy or opinion be right?

"Her. Hardly so neither, I think; yet sure the wise and good Author of Nature could never make us to plague us. He could never give us passions, on purpose to subdue and conquer 'em; nor produce this self of mine, or any other self, only that it may be denied; for that is denying the works of the great Creator Himself. Self-denial, then, which is what I suppose you mean by prudence, seems to me not only absurd but very dishonourable to that supreme Wisdom and Goodness. . . . Are we created sick, only to be commanded to be sound? Are we born under one law, our passions, and yet bound to another, that of reason? Answer me, Philocles, for I am warmly concerned for the honour of Nature, the mother of us all. . . .

"Phil. This, my dear Horatio, I have to say: that what you find fault with and clamour against, as the most terrible evil in the

PHILADELPHIA Master : 8$

world, self-denial, is really the greatest good and the highest self-gratification. If, indeed, you use the word in the sense of some weak sour moralists, and much weaker divines, you'll have just reason to laugh at it. But if you take it as understood by philosophers and men of sense, you will presently see her charms, and fly to her embraces, notwithstanding her demure looks, as absolutely necessary to produce even your own darling sole good, pleasure; for self-denial is never a duty, or a reasonable action, but as 'tis a natural means of procuring more pleasure than you can taste without it. . . .

""Hor. . . . I'm impatient, and all on fire. Explain, therefore, in your beautiful, natural, easy way of reasoning, what I'm to understand by this grave lady of yours, with so forbidding, downcast looks, and yet so absolutely necessary to my pleasures. I stand ready to embrace her; for, you kno^\', pleasure I court under all shapes and forms.