Genesis Rabbah 98, 17 - “And Why Is It Called Gennosar?” Recent Discoveries at Magdala and Jewish Life on the Plain of Gennosar in the Early Roman Period

It has been more than ten years since the death of my teacher, David Flusser  . He continued to work even while ailing, and one of the last studies he wrote from his hospital bed was a short two-page article on Genesis Rabbah 98:17.398 While the study is brief, it is Flusser’s typical approach to such questions, a combination of his mastery of historical philology and an intimate knowledge of the contours of the Jewish and classical sources. This essay follows upon Flusser’s line of inquiry, considering the plain of Gennesar from a historical-geographical perspective and concludes with consideration of recent archaeology activity at Magdala (Figs. 1–3). I suggest that together the literary, topographical and archaeological evidence points us to a priestly presence in the region from the days of the Hasmoneans until the aftermath of the Bar Kokhba Revolt.

. He continued to work even while ailing, and one of the last studies he wrote from his hospital bed was a short two-page article on Genesis Rabbah 98:17.398 While the study is brief, it is Flusser’s typical approach to such questions, a combination of his mastery of historical philology and an intimate knowledge of the contours of the Jewish and classical sources. This essay follows upon Flusser’s line of inquiry, considering the plain of Gennesar from a historical-geographical perspective and concludes with consideration of recent archaeology activity at Magdala (Figs. 1–3). I suggest that together the literary, topographical and archaeological evidence points us to a priestly presence in the region from the days of the Hasmoneans until the aftermath of the Bar Kokhba Revolt.

1 Who is the Ruler of Gennesar?

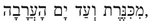

In Genesis Rabbah we hear a toponymic discussion pertaining to the geographical boundaries mentioned in Deuteronomy 3:17:  “from Kinnereth to the Sea of the Arabah.” The midrashic discussion is focused primarily on the toponym

“from Kinnereth to the Sea of the Arabah.” The midrashic discussion is focused primarily on the toponym  :

:

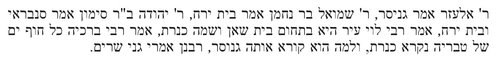

R. Eleazar said: This is the Gennesar.

R. Samuel b. Nahman said: It is Beth Yerah.

R. Judah b. R. Simon said: It is Sennabris and Beth Yerah.

R. Levi said: There is a town within the environs of Beth Shean called Kinneret. R. Berekiah said: The whole shore of the Lake of Tiberias is called Kinneret. Now why is it called Gennosar? The Rabbis said: [Gennesar] means the gardens of the rulers.

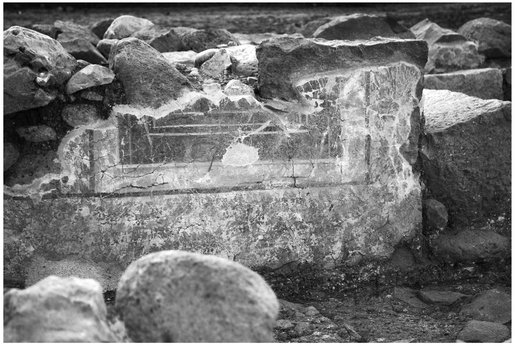

Fig. 1: Stone table in bas relief, Magdala (end view). Courtesy of R. Steven Notley.

Albeck’s critical edition of Genesis Rabbah prefers the reading of the London manuscript’s spelling of the toponym as  , which is the form adopted by modern Hebrew, while manuscript variants provided in the apparatus offer

, which is the form adopted by modern Hebrew, while manuscript variants provided in the apparatus offer  and

and  .399 The etymology pursued by the Rabbis at the conclusion of our tradition in the context assumes the variant reading of

.399 The etymology pursued by the Rabbis at the conclusion of our tradition in the context assumes the variant reading of  – gardens of (the) ruler.400 This is likewise the spelling provided a few lines earlier in the statement by R. Eleazar. The reading of

– gardens of (the) ruler.400 This is likewise the spelling provided a few lines earlier in the statement by R. Eleazar. The reading of  rather than

rather than  is also supported by the pronunciation of the earliest literary reference to Gennesar, which is found in the Greek text of 1 Maccabees (

is also supported by the pronunciation of the earliest literary reference to Gennesar, which is found in the Greek text of 1 Maccabees ( =

=

), as well as, the best readings for the toponym found in MS Codex Bezae of Matthew 14:34 and Mark 6:53 (

), as well as, the best readings for the toponym found in MS Codex Bezae of Matthew 14:34 and Mark 6:53 ( ).401 Finally, it accords with the Latin equivalent reported by the Roman historian Pliny the Elder (d. 79

CE) in his single use of our toponym to designate the lake: in lacum se fundit quem plures Genesaram vocant, “[the Jordan River] widens into a lake that is usually called Gennesar” (Natural History 5.71).

).401 Finally, it accords with the Latin equivalent reported by the Roman historian Pliny the Elder (d. 79

CE) in his single use of our toponym to designate the lake: in lacum se fundit quem plures Genesaram vocant, “[the Jordan River] widens into a lake that is usually called Gennesar” (Natural History 5.71).

The author of 1 Maccabees uses Gennesar to describe the campaign of Jonathan son of Mattathias on his march to Hazor: “Jonathan and his army encamped by the waters of Gennesar. Early in the morning they marched to the plain of Hazor” (1 Maccabees 11:67).402 However, there is little question that use of the toponym in connection with Jonathan’s campaign is anachronistic. We have no evidence for such an early use of Gennesar. Instead, it represents the toponymic usage at the time of the work’s composition rather than the events described.403 “The waters of Gennesar” in 1 Maccabees refers to the Kinneret Lake.404 Josephus likewise reports that the lake was identified by the local inhabitants with the plain of Gennesar: “... the lake, which the native inhabitants call Gennesar” (War 3:463; see also 2:573; 3:506; Antiquities 18:28, 36). In a previous study, I have shown that the name for the lake found in the New Testament - the Sea of Galilee (θἀλασσα τῆϚ Γαλιλαίας) - is a Christian invention.405 Not only do Matthew, Mark and John incorrectly describe the body of water as a θἀλασσα (i.e., sea) rather than a λίμνη (i.e., lake),406 outside of these works the toponym, Sea of Galilee, never appears in Hebrew, Aramaic, Greek or Latin literature before the Byzantine period. Luke alone of the Evan gelists correctly describes the lake with λίμνη and knows it by the name Gennesar. 407 As such, he accords with the testimony of Josephus that the most common designation by local inhabitants identified the lake with the alluvial plain on its northwest shore. Of course, the use of Gennesar to identify the lake is also the premise for R. Eleazar’s identification of  and

and  in Genesis Rabbah.

in Genesis Rabbah.

Based upon the reading of  , Flusser pursued the question, “Who are the

, Flusser pursued the question, “Who are the  mentioned by the Sages?” His answer was deduced from the development of political terminology in the Hasmonean period. The first two generations of Hasmonean priestly leaders did not take on the title “king.” However, these hesitations evaporated during the reign of Judah Aristobulus, son of John Hyrcanus, who according to Josephus, “transformed the government into a monarchy, and was the first [of the Hasmoneans] to assume the diadem” (War 1:70). His report differs from that of the Greek geographer, Strabo, who credits the change with Aristobulus’ brother, Alexander Jannaeus (Geography 16.2.40). Perhaps because of the brevity of Aristobulus’ one year reign, there remains some question regarding the changes that occurred during this transitional year. In any event, the epigraphical evidence from the coinage of Jannaeus indicates that at least by his reign the supreme ruler in the nation was called high priest and king.408

mentioned by the Sages?” His answer was deduced from the development of political terminology in the Hasmonean period. The first two generations of Hasmonean priestly leaders did not take on the title “king.” However, these hesitations evaporated during the reign of Judah Aristobulus, son of John Hyrcanus, who according to Josephus, “transformed the government into a monarchy, and was the first [of the Hasmoneans] to assume the diadem” (War 1:70). His report differs from that of the Greek geographer, Strabo, who credits the change with Aristobulus’ brother, Alexander Jannaeus (Geography 16.2.40). Perhaps because of the brevity of Aristobulus’ one year reign, there remains some question regarding the changes that occurred during this transitional year. In any event, the epigraphical evidence from the coinage of Jannaeus indicates that at least by his reign the supreme ruler in the nation was called high priest and king.408

At the beginning of the Hasmonean Revolt, the rededication of the Temple in December, 166 BCE marked a measure of autonomy under Judah and subsequently his brother Jonathan. Yet, historians identify full Jewish independence with the rule of Simon and the permission granted him to mint coins (1 Maccabees 15:6).409 His ascent to supreme leader also marked a new era: “In the one hundred seventieth year the yoke of the Gentiles was removed from Israel, and the people began to write in their documents and contracts, ‘In the first year of Simon the great high priest and commander and leader of the Jews’” (1 Maccabees 13:41-42).410 The authority vested in him was proclaimed by a great assembly convened in Jerusalem, as we hear at his installation.411

The people saw Simon’s faithfulness and the glory that he had resolved to win for his nation, and they made him their ruler and high priest ( ), because he had done all these things and because of the justice and loyalty that he had maintained toward his nation. He sought in every way to exalt his people (cf. 1 Maccabees 14:35; cf. Antiquities 13:201).

), because he had done all these things and because of the justice and loyalty that he had maintained toward his nation. He sought in every way to exalt his people (cf. 1 Maccabees 14:35; cf. Antiquities 13:201).

“The Jews and their priests have resolved that Simon should be their ruler and high priest forever ( ), until a trustworthy prophet should arise” (1 Maccabees 14:41).

), until a trustworthy prophet should arise” (1 Maccabees 14:41).

In both these passages, the Greek term used for the political office of Simon is  , the Greek equivalent for

, the Greek equivalent for  (cf. LXX 1 Kings 22:2; 2 Kings 3:38; 4:2; etc.).412 Previous use of the Greek term in 1 Maccabees conveyed the idea of military leadership (1 Maccabees 3:55; 5:6, 11; 5:18; 7:5; 9:30 et passim). What marks the change in the term’s use is its collocation with “priest” to form a dual title: ruler and high priest. It seems that this title was adopted at the appointment of Simon and repeated by his son, John Hyrcanus. Its dual form likewise anticipated another titular change when Simon’s grandsons assumed the throne. For the first time, the Hasmonean high priests adopted the title: high priest and king.

(cf. LXX 1 Kings 22:2; 2 Kings 3:38; 4:2; etc.).412 Previous use of the Greek term in 1 Maccabees conveyed the idea of military leadership (1 Maccabees 3:55; 5:6, 11; 5:18; 7:5; 9:30 et passim). What marks the change in the term’s use is its collocation with “priest” to form a dual title: ruler and high priest. It seems that this title was adopted at the appointment of Simon and repeated by his son, John Hyrcanus. Its dual form likewise anticipated another titular change when Simon’s grandsons assumed the throne. For the first time, the Hasmonean high priests adopted the title: high priest and king.

Because of its narrow window of titular usage, Flusser suggested that the  in Genesis Rabbah should be identified with the Hasmoneans who took upon themselves the epithet

in Genesis Rabbah should be identified with the Hasmoneans who took upon themselves the epithet  ; namely, Simon and his son John Hyrcanus. Flusser’s suggestion is strengthened by the appearance of

; namely, Simon and his son John Hyrcanus. Flusser’s suggestion is strengthened by the appearance of  in 1 Maccabees. This work was composed during the rule of John Hyrcanus and so serves as a terminus ad quem for the individual identified in the toponym.

in 1 Maccabees. This work was composed during the rule of John Hyrcanus and so serves as a terminus ad quem for the individual identified in the toponym.

The church historian, Eusebius of Caesarea (d. 339), corroborates this interpretation. Concluding his citation from Origen regarding the list of the Hebrew canon he adds, “And outside these are the (Book of) Maccabees, which are entitled Sar beth sabanai el ( )” (Ecclesiastical History 6:25). There is little doubt that the title of the work has been corrupted, but it is equally clear that it attests to the historian’s familiarity with the existence of a Hebrew version of 1 Maccabees at the beginning of the 4th century CE Various conjectures have been advanced for the Hebrew title, but the most

likely seems to read

)” (Ecclesiastical History 6:25). There is little doubt that the title of the work has been corrupted, but it is equally clear that it attests to the historian’s familiarity with the existence of a Hebrew version of 1 Maccabees at the beginning of the 4th century CE Various conjectures have been advanced for the Hebrew title, but the most

likely seems to read  : The Book of the Dynasty of the Ruler of the People of God413 The fact that the work follows the history of the Hasmoneans to include the advent of John Hyrcanus - but not his sons - concurs with Flusser’s contention that the

: The Book of the Dynasty of the Ruler of the People of God413 The fact that the work follows the history of the Hasmoneans to include the advent of John Hyrcanus - but not his sons - concurs with Flusser’s contention that the  in the title

in the title  can not be identified with the Hasmoneans who rose subsequent to John Hyrcanus.

can not be identified with the Hasmoneans who rose subsequent to John Hyrcanus.

If Simon and his son bore the title  , then the tradition from Genesis Rabbah may in fact remember agricultural lands adjoining the lake that came into the possession of this priestly clan. We have no record of Simon residing in the Galilee. Instead, he settled in Gazara (1 Maccabees 13:43-48).414 However, recent archaeological surveys indicate a significant increase in Jewish settlement in Galilee following John Hyrcanus’ conquest of Scythopolis (cf. War 1:66).415 During this same time Josephus reports that Alexander Jannaeus, son of John Hyrcanus, was “brought up in Galilee from his birth” (Antiquities 13:322). While there remain scholarly questions about both the specifics and the motivation for Hyrcanus sending his son to Galilee, the report does provide historical testimony that coincides with the archaeological evidence for a Hasmonean presence in Galilee in the days of John Hyrcanus. Unfortunately, Josephus does not give us details about where Alexander Jannaeus lived.416 While his residence must remain an open question, it is worth noting that the foundations for the settlement of Magdala date to this period and adjoin agricultural lands that Flusser argues were in possession of the Hasmonean, as indicated by the etymology of Gennesar.

, then the tradition from Genesis Rabbah may in fact remember agricultural lands adjoining the lake that came into the possession of this priestly clan. We have no record of Simon residing in the Galilee. Instead, he settled in Gazara (1 Maccabees 13:43-48).414 However, recent archaeological surveys indicate a significant increase in Jewish settlement in Galilee following John Hyrcanus’ conquest of Scythopolis (cf. War 1:66).415 During this same time Josephus reports that Alexander Jannaeus, son of John Hyrcanus, was “brought up in Galilee from his birth” (Antiquities 13:322). While there remain scholarly questions about both the specifics and the motivation for Hyrcanus sending his son to Galilee, the report does provide historical testimony that coincides with the archaeological evidence for a Hasmonean presence in Galilee in the days of John Hyrcanus. Unfortunately, Josephus does not give us details about where Alexander Jannaeus lived.416 While his residence must remain an open question, it is worth noting that the foundations for the settlement of Magdala date to this period and adjoin agricultural lands that Flusser argues were in possession of the Hasmonean, as indicated by the etymology of Gennesar.

Returning to our passage from Genesis Rabbah once again: “R. Berekhiah said: All the shore of the lake of Tiberias is called Kinneret. Now why is it called Gennesar?” What can be easily overlooked in the rabbinic deliberation is that the later third century amora R. Berekiah’s question assumes the most frequent use for the toponym Gennesar.417 In spite of continued attempts to locate a settlement of Gennesar,418 the occurence of the toponym in the ancient sources never describes a settlement, village or town. It occurs most frequently to designate the lake (e.g. b. Megillah 6a). Otherwise, it is used to describe the lush agricultural area northwest of the lake. Indeed, later midrashic texts, such

as Ruth Rabbah 6:4, we hear the expression  (i.e., the valley of Gennesar), while in b. Baba Batra 122a we find the designation

(i.e., the valley of Gennesar), while in b. Baba Batra 122a we find the designation  (i.e., the region of Gennesar).

(i.e., the region of Gennesar).

The plain of Gennesar (or el-Ghuweir as it is known in Arabic419) measures approximately 3.5 miles by 1.5 miles, and its position 660 feet below sea level provides a temperate climate that combined with its fertile soil gives it ideal growing conditions.420 B. Pesahim 8b speaks of the,  , “the fruits of Gennosar”, and Josephus paints an idyllic picture of the region:

, “the fruits of Gennosar”, and Josephus paints an idyllic picture of the region:

Skirting the lake of Gennesar, and also bearing that name, lies a region whose natural properties and beauty are very remarkable. There is not a plant which its fertile soil refuses to produce, and its cultivators in fact grow every species; the air is so well-tempered that it suits the most opposite varieties. The walnut, a tree which delights in the most wintry climate, here grows luxuriantly, beside palm-trees, which thrive on heat, and figs and olives, which require a milder atmosphere. One might say that nature had taken pride in thus assembling, by a tour de force, the most discordant species in a single spot, and that, by a happy rivalry, each of the seasons wished to claim this region for her own. For not only has the country this surprising merit of producing such diverse fruits, but it also preserves them: for ten months without intermission it supplies those kings of fruits, the grape and the fig; the rest mature on the trees the whole year round. Besides being favored by its genial air, the country is watered by a highly fertilizing spring, called by the inhabitants Capernaum ... This region extends along the border of the lake which bears its name for a length of thirty furlongs and inland to a depth of twenty. Such is the nature of this district (War 3:516-521, Thackeray).

Our purpose in citing Josephus’ description in full is to underscore that when mention is made of the plain of Gennesar, it is usually to its agricultural characteristics, precisely the essence of the rabbinical etymology for  , Gennesar.

, Gennesar.

During the last decade Leibner conducted a survey of the el-Ghuweir plain in hopes of identifying the ancient settlement of Gennesar.421 His survey identified six sites that warranted archaeological analysis: Tell el-‘Oreimeh (Kinne-rot), Khirbet el-Minye, Tell el-Hunud, Nun,422 Majdal/Magdala and Ghuweir Abu Shushe. On the basis of his survey, surface finds and previous archaeological investigations most sites were eliminated from consideration because of their lack of occupation during the periods when Gennesar is attested in the historical sources (i.e. Hellenistic and Roman). These were occupied only in earlier or later periods with no material evidence for the time in question.

Two sites evidenced activity during the late Hellenistic (Hasmonean) and Roman periods: Majdal/Magdala and Ghuweir Abu Shushe. Regarding the former, Leibner summarily dismissed it, noting that the evidence “pointed to the establishment of this settlement only during the Hasmonean period, towards the end of the 2nd/start of the 1st c. BC”423 His decision to discount Magdala from consideration seems based solely upon the reference to “the waters of Gennesar” in the campaign of Jonathan in 145 BCE He reasoned that at the time of the campaign, “Gennesar was an established place which had already given the lake its name. Thus Gennesar cannot be identified with Majdal.” 424 While we are not suggesting that Magdala be identified with Gennesar, Leibner has misunderstood the chronological significance of Gennesar in 1 Maccabees. As we have stated, the toponym in the episode is anachronistic and reflects usage at the time the work was composed, not necessarily at the time of the events described. On the other hand, Leibner states that the material evidence confirms Magdala was settled towards the end of the 2nd century BCE precisely when the references to Gennesar begin to appear.425 There is nothing to prevent Gennesar from designating the arable lands that surrounded Magdala, which in all probability belonged to those who resided in the new settlement.426 Of course, we have nothing in the ancient sources to tell us who owned these lands, but it is not unreasonable to assume a connection between Magdala and its surroundings.

2 Magdala-Tarichaea

Already in the first century BCE Magdala-Tarichaea was the largest settlement on the western shore of lake (War 1:180). The city is well attested. Josephus alone mentions it forty-seven times by its Greek name Tarichea.427 Both its Hebrew and Greek names, Migdal-Nunia (“fish tower”)428 and Tarichea (“salted fish”)429 reflect the dominant local industry.430 According to Strabo, “At the place called Tarichaea the lake supplies excellent fish for pickling; and on its banks grow fruit-bearing trees resembling apple trees” (Geography. 16.2.45).

In the New Testament there is only indirect reference to Magdala - as the home of Mary Magdalene ( ).431 A one-room building within the ruins was the subject of an earlier debate. Corbo, who excavated the site, suggested that it was a small synagogue, while Netzer pointed to adjacent canals to contend that the structure was a springhouse.432 Nevertheless, the recent finds at Magdala, which we will consider below, have made this issue a moot point.

).431 A one-room building within the ruins was the subject of an earlier debate. Corbo, who excavated the site, suggested that it was a small synagogue, while Netzer pointed to adjacent canals to contend that the structure was a springhouse.432 Nevertheless, the recent finds at Magdala, which we will consider below, have made this issue a moot point.

Travel between Tiberias and Magdala is described in rabbinic literature433 and earlier Josephus, who speaks of “a road to Tarichea, which is thirty furlongs [ca. 3.5 mi] distant from Tiberias” (Life 157). His description is to be preferred to Pliny’s placement of Tarichea south of the Kinneret Lake, “Tarichea on the south (a name which is by many persons given to the lake itself), and of Tiberias on the west” (Natural History 5:15). Pliny’s misplacement notwithstanding, we may witness the influence of the close association between Magdala-Tarichaea and Gennesar in Pliny’s confused testimony that Tarichaea gave its name to the lake (see also War 3:463). No ancient witness adopts the toponym Magdala or Tarichaea to name the lake. Instead, it is the arable lands that surround Magdala-Tarichea that served as the germ for the lake’s popular toponym.

Josephus presents Tarichea at the center of its own toparchy in 54 CE when the city was awarded by Nero to Agrippas II (War 2:252; Antiquities 20:159).434 Together with the toparchy of Tiberias, Tarichea comprised eastern Galilee (War 2:252). Its continued prominence almost forty years after the founding of Tiberias underscores the importance of Magdala-Tarichea in the life and commerce of the population in the region. A decade later Josephus was given the responsibility for the defense of the Galilee, and he included Tarichea in a list of cities of Lower Galilee that he fortified in preparation for war with Rome (Life 188; 156). At this time no walls, nor the hippodrome which he also describes, have yet been discovered. Suetonius mentions the conquest of Tarichea and Gamala by Titus (Titus 4:3), while Josephus describes the sea-battle at Tarichea (War 3:522-531) that resulted in a devastating Jewish loss. Residents fled to Tiberias thinking they would not be able to return.435

The Talmudic name for Magdala (

) was attested in an archaeological discovery in 1956 from the remains of a late Roman (3rd–4th c. CE) synagogue at Caesarea.436 Three fragments survived from a marble slab, which “together enable us to restore the whole of the inscription...Each line includes the number of the [priestly] course, its name and appellation (if it had one) and the village or town it inhabited after the destruction of the Temple.”437 A similar inscription of the priestly courses was found at Ashkelon.438 Based in part on piyyutim found in the Cairo Genizah, Avi-Yonah suggested the line in which Magdala occurs should read:

) was attested in an archaeological discovery in 1956 from the remains of a late Roman (3rd–4th c. CE) synagogue at Caesarea.436 Three fragments survived from a marble slab, which “together enable us to restore the whole of the inscription...Each line includes the number of the [priestly] course, its name and appellation (if it had one) and the village or town it inhabited after the destruction of the Temple.”437 A similar inscription of the priestly courses was found at Ashkelon.438 Based in part on piyyutim found in the Cairo Genizah, Avi-Yonah suggested the line in which Magdala occurs should read:

— “The 20th course Ezekiel MI]GDAL [Nunaiya.”439 Archaeological evidence for the use of the Mishmarot (1 Chronicles 25:7—18) during the days the Second Temple

was already demonstrated with its discovery in the library at Qumran.440 Avi-Yonah ventured that the geographical territories of the twenty-four priestly courses may have been identical to the administrative units into which the Jewish land was divided, “15 such toparchies in Judea (including Idumea), one in Samaria, three in Perea, and five in Galilee, twenty-four in all. ”441 He concluded that the Caesarea inscription establishes a priestly presence in Galilee in the aftermath of the destruction of the Temple in 70 CE and the reorganization that ensued after the fall of Betar in 135 CE. Of course, already in the days of the Temple, we hear of priests who lived in Galilee (m. Yoma 6:3; t. Sotah 13:8; y. Yoma 6:3c).442

— “The 20th course Ezekiel MI]GDAL [Nunaiya.”439 Archaeological evidence for the use of the Mishmarot (1 Chronicles 25:7—18) during the days the Second Temple

was already demonstrated with its discovery in the library at Qumran.440 Avi-Yonah ventured that the geographical territories of the twenty-four priestly courses may have been identical to the administrative units into which the Jewish land was divided, “15 such toparchies in Judea (including Idumea), one in Samaria, three in Perea, and five in Galilee, twenty-four in all. ”441 He concluded that the Caesarea inscription establishes a priestly presence in Galilee in the aftermath of the destruction of the Temple in 70 CE and the reorganization that ensued after the fall of Betar in 135 CE. Of course, already in the days of the Temple, we hear of priests who lived in Galilee (m. Yoma 6:3; t. Sotah 13:8; y. Yoma 6:3c).442

3 A Menorah at Magdala

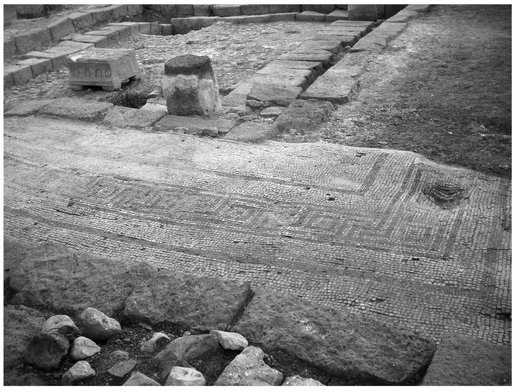

In July 2009 excavations began at Magdala in advance of the construction of a Christian pilgrimage center under the auspices of the Roman Catholic order, the Legionaires of Christ.443 The excavations have been carried out by the IAA under the direction of Dina Avshalom-Gorni and Arfan Najar.444 Within the first month of excavations they discovered an 1080 square foot (c. 120 sq. m.) building that the excavators suggest was destroyed in the Jewish Revolt.445 The archaeologists claim that the building was the synagogue of Magdala. If so, the building at Magdala joins six other synagogues that have been identified from the period of Jerusalem’s Second Temple.446

For the purposes of our study, it is not decisive whether or not the structure was used as a synagogue. The debate over identifying ancient synagogues is well known. However, there is little question that this structure is unique when compared to the other six synagogues. None is so lavishly decorated. The building was decorated with Pompeian First Style frescoes.447 These are characterized by their imitation of marble and use of vivid color, both being a sign of wealth. They were a replica of those found in the Ptolemaic palaces of the Near East, where the walls were inset with real stones and marbles, and they also reflect the spread of Hellenistic culture when Rome conquered and interacted with other Greek and Hellenistic states in this period.

We often find such frescoes in the homes of the wealthy, aristocratic stratum of society who could afford such amenities. A contemporary example is the frescoes from the palatial priestly homes of Jerusalem in which we were found the graffiti of the menorah and shewbread table.448 Another example is the royal box of the small theater at Herodium, built by Herod the Great in anticipation of the visit to Judea by Marcus Agrippa in 15 BCE (Antiquities 16:12-15; Legation 294-297).449 The frescoes of Herodium belong to the Pompeian Late Second Style reflecting Herod’s attempt to remain contemporary.450 In addition, the Magdala synagogue had ornate mosaic floors with a meander pattern, also a feature seen in both the palatial Jerusalem homes and Herodian palaces. To repeat, no other synagogue of the Second Temple period has yet been discovered that was so richly adorned.

On January 9, 2010 the author led a group of students from Nyack College to view the excavations at the invitation of Fr. Juan Maria Solana from the Notre Dame Center, Jerusalem. Although the mosaics and frescoes were remarkable, the most striking feature was an ornately decorated stone table that stood within the structure. After the visit, we discovered we were the last to see the engraved table in situ. The next day it was removed to the Rockefeller Museum in Jerusalem for testing and further examination. The table is engraved on its four sides and top. On one narrow side are two six-petalled rosettes set within pillared arched openings. Each of the two wide sides of the table present three sheaves of grain and an oil lamp. The style of the lamp on these sides resembles those of the late Hellenistic and early Herodian period,451 which may suggest that the age of the table predates the structure in which it stood. Engraved on the tabletop are two palm trees and another six-petalled rosette. Other geometric shapes decorate the top, but there is uncertainty concerning their significance. At each of the four corners of the tabletop there is a slightly recessed, unworked area. These recessed corners may give some hint concerning the table’s use (e.g., pedestal for a Torah stand, ornate lampstand, etc.).

The remaining narrow side of the table has attracted the most attention. It has two engraved columns between which are two amphorae and a menorah at the center. According to the excavators, this is the first time that a menorah “decoration” has been discovered in situ from the days when the Second Temple was still standing. While perhaps a bit overstated, the claim of the excavators rings true: “We can assume that the engraving that appears on the stone was done by an artist who saw the seven-branched menorah with his own eyes in the temple in Jerusalem.”452

The excitement surrounding the discovery is because of the rarity of finding depictions of the menorah during the days of the Second Temple. According to Rahmani, “Representations of menorot from before 70 CE, as well as the depiction of an altar, must be associated with the Temple priesthood, for whom the seven-branched menorah seems to have been an emblem.”453 His observation may be born out in many cases when the context for the menorahs is known. The oldest representation of the menorah from the Second Temple period is the coin of Mattathias Antigonus, the last of the Hasmonean Kings (40-37 BCE, Fig. 4).454 On the coin’s obverse is the shewbread table. “Around the table appears a Hebrew inscription ... it is possible to reconstruct it from several coins:  , (Mattiyah high priest’).” 455 On the reverse is the seven-branched menorah with a flared base.456 “The Greek inscription reads:

, (Mattiyah high priest’).” 455 On the reverse is the seven-branched menorah with a flared base.456 “The Greek inscription reads:  (‘of King Anti[gonus]’).”457 This is the only Jewish coin in antiquity that depicts the menorah. Even the Bar Kokhba coins that are noted for their Temple motifs do not include the menorah.458

(‘of King Anti[gonus]’).”457 This is the only Jewish coin in antiquity that depicts the menorah. Even the Bar Kokhba coins that are noted for their Temple motifs do not include the menorah.458

Fig. 4: Coin of Mattathias Antigonus with the menorah and table of showbread, 39 BCE (Courtesy of David Hendin).

A menorah appears among graffiti found in a palatial home from Jerusalem dating to the early Herodian period that archaeologists identify as a priestly residence.459 Similar to the coin of Mattathias Antigonus, the graffiti depict the menorah with a flared base beside the shewbread table.460 In addition, the graffiti include the incense altar. The co-appearance of the menorah and the shewbread table on both the Hasmonean coin and the Jerusalem graffiti - their earliest depictions in the Roman period - may present a solution to a question that has stymied archaeologists and historians alike; namely the subsequent portrayal of the menorah with a square base, rather than the flared triangular base seen with the coin and the graffiti.461

Beginning with two incised graffiti of menorahs from Jason’s tomb - which may or may not have belonged to a priestly family,462 a sundial with an engraved menorah found near the Temple Mount,463 the menorah from Magdala and what may be a five-branched menorah from the City of David excavations, 464 there has been debate about the significance of the menorah’s appearance with a square base.465 The coin and the graffiti from the palatial Jerusalem residence suggest the alleged variation might be an optical illusion. Is it possible that rather than a square base, the artists have juxtaposed the menorah to stand behind the shewbread table, giving the two-dimensional illusion of a single piece of furniture with the lower portion of the lampstand eclipsed by the table? Our suggestion is strengthened by the fact that the continuation of the vertical post of the lampstand is clearly visible within - and distinct from - the square “base” in the cases of Jason’s Tomb, the sundial and the five-branched menorah from the City of David. The flared base of the earlier examples is stylistically repeated in the Magdala menorah above the table, and a three-pronged base is visible within the etched square below the five-branched menorah from the City of David.

Another object appearing with the Magdala menorah has a parallel. According to Rahmani, two ossuaries belonging to priests are decorated with menorahs.466 In one a five-branched menorah replaces the ‘triglyph’ in a metope scheme and appears between two amphorae, the same arrangement we see on the engraved table from Magdala.467 One can not be certain whether the amphorae were intended to contain water, wine or oil.468 If they are for wine libations, the side panels of the table with the wine amphorae, sheaves and oil lamps might represent the agricultural produce of the region that were contributed to the Temple: wine, grain and oil.469

Our interest in comparing the menorah from Magdala to other known examples has not been primarily to resolve the ongoing debate regarding the base of the menorah that stood in Jerusalem’s Temple. Still, as sometimes happens, a tangential study can bring an unexpected discovery. We have found that the square figure that repeatedly appears with pre-70 CE menorahs was intended to represent the shewbread table. It can hardly be a coincidence that the menorah with the square base never appears separately with the shewbread table, and when the shewbread table appears together with - but distinct from - the menorah, the lampstand never has a square base. More important for the purposes of our study is the realization that the menorah from Magdala evinces the same reality that scholars have associated with the others. Following the estimation of Rahmani, the menorah may signal a priestly presence at Magdala during the final decades of the Second Temple. Thus, the archeological discovery at Magdala corresponds with Flusser’s historical reading of the etymology of Gennesar - which marks the initiation of a priestly presence on the plain of Gennesar from the days of John Hyrcanus - and it serves as a bridge to the later witness of the Caesarea inscription of a priestly presence at Magdala on the plain of Gennesar in the aftermath of the Bar Kokhba Revolt. So, in Genesis Rabbah 98:17 when the Rabbis derive  from

from  , this is not mere fanciful wordplay, but an historical memory concerning the Hasmonean beginnings of priestly residence on the fertile shores of the waters of Gennesar.

, this is not mere fanciful wordplay, but an historical memory concerning the Hasmonean beginnings of priestly residence on the fertile shores of the waters of Gennesar.