So you’re not only touching the blackness, you’re touching the Left …

—FRANCES BARRETT WHITE, 1951

IN 1940, CHARLES WHITE completed his third large mural,

A History of the Negro Press,

1 a nine-by-twenty-foot oil painting commissioned by the Associated Negro Press, to represent the historical progress of the black press. The mural was exhibited at the huge African American Exhibition of the Art of the American Negro, which was held at the South Side Chicago Coliseum in July 1940 to commemorate the seventy-fifth anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation (Mullen 1999, 75). At the time White was at the Mural Division of the Illinois Federal Art Project, where he worked with two left-wing artists, Edward Millman and Mitchell Siporin. Organized by two Howard University professors—Alonzo Aden, the curator of Howard’s art gallery, and Alain Locke, a professor of philosophy and major African American cultural critic—the 1940 exhibition was a milestone for the twenty-two-year-old White. He won acclaim and a first prize for his mural, which, until it was either lost or destroyed, was on display in the offices of the

Chicago Defender.

The mural features eleven male figures engaged in the production of black newspapers. In the center of the left half of the mural are the three titans of the black press: John Russworm, the founder of the first black newspaper in 1827,

Freedom’s Journal, holds a series of broadsides spread out before him. Above him and to his left is Frederick Douglass, the founder of the 1847 abolitionist paper the

North Star, with a full head of white hair and beard and his arm around a former slave. Centered at the apex of this triumvirate, to Douglass’s right, with his signature professorial black-rimmed glasses, vest, and tie, is T. Thomas Fortune, the editor of the militant

New York Age, founded in the early 1880s. At the bottom left is a man reading the paper and another with the torch that White often used to represent militant struggle. The four figures on the right side of the mural represent the contemporary black press. One man in a reporter’s trench coat, his press pass tucked into the rim of his fedora, takes notes on a tablet. To his right a photographer holds a large flashbulb camera, and to his left is the operator of the printing press standing next to the machine that spins out the news of the day. The mural is balanced with a man setting type on the far left and the modern printing press on the right half. In this early work, the visual chronicle of the hundred-year history of the black press, White’s investment in the modern is clearly on display, in the swirling lines that give a sense of deliberate but accelerating motion of progress, in the large and angular stylized hands, in the geometric lines repeated in the facial features of each of the eleven men, and in the way the history of the press is compressed into this single visual moment. But what is most modern in the drawing is the relationship between the men and the machines: the eleven men—printers, call boy, mechanics, photographer, and reporter—all are totally at ease, calmly poised before, in control of, and helping produce the forces of modernity unleashed by the machines (Clothier n.d.).

2

Source: Photograph by Frank J. Thomas. Courtesy of the Frank J. Morgan Archives.

White’s biographer Peter Clothier was the first to call my attention to what he refers to as the mural’s “stylistic contradictions,” the tension between representational realism and modernist experimentation (68).

3 On the one hand we see White’s modernist tendencies in the enlarged hands and arms and in the mural’s theme of black progress, but the mural is clearly representational, the narrative easily accessible, the figures only slightly stylized. The mural serves as an interpretive context for understanding a decades-long interplay between White’s social realism and his commitment to a modernist art. While White’s critics most often situate him within an African American cultural context because of his desire to historicize and celebrate black culture, few acknowledge his affiliations with the Left and with the Communist Party. I argue that we cannot understand White’s work, especially his commitment to social realism, without considering how these “stylistic contradictions” are rooted in his dual role as artist and political activist in the context of a U.S. and an international Left, specifically during the 1940s and 1950s. If White was leaning toward more experimental forms in his work, he would eventually have to decide if and how these forms could be made compatible with the radical Left’s advocacy of a democratic people’s art predicated on the political potential of beautiful, realistic, accessible images of black people and black culture.

It is important to emphasize that White’s commitment to a black cultural aesthetic predated his affiliation with the Communist Party. As far back as his teenage years in Chicago he describes discovering the beautiful black faces in Alain Locke’s 1925 The New Negro, which confirmed his fascination with blackness. White’s close friend, the writer John O. Killens, insisted that beyond celebrating blackness, White was intent on establishing a new aesthetic: “The people Charlie brings to life are proudly and unabashedly black folk, Africans, with thick lips and broad nostrils. Here are no Caucasian features in blackface, but proud blacks—bigger than life, in epic and heroic proportions” (1968, 451). Another of White’s close friends, the artist Tom Feelings, an even more perceptive critic, adds that White’s aesthetic was attentive to class as well as race:

Though his active interest led him to draw and paint great historical figures from black history, I believe that in most of his artwork Charles White purposely chose to depict the everyday, ordinary, working-class people, the most African-looking, the poorest, and the blackest people in our ranks. The ones who by all accounts were the furthest from the country’s white standards of success and beauty.

(1986, 451)

In effect, White was constructing a black radical subjectivity, a visual analogue of the radical work being done by black leftist writers that would eventually force his personal and aesthetic crisis with the Left.

Publicly and privately, White espoused the ideals of Marxism, and, at least until 1956, he was involved with the institutions that the Communist Party led or influenced—associations that supported both his personal ideals and his art.

4 During his more than forty years as an artist, White created a visual archive of more than five hundred images of black Americans and black American history and culture. His portraits of historical figures including Frederick Douglass, John Brown, Sojourner Truth, Harriet Tubman, Leadbelly, and Paul Robeson have become signatures of his artistic legacy. His great murals, such as

The Contribution of the Negro to Democracy in America (1943),

A History of the Negro Press, and

Five Great American Negroes (1939–1940), are almost immediately recognizable as White’s work. He developed a highly respected reputation in both black and white communities because he worked to make his art more accessible—financially as well as aesthetically—to working-class people. He produced his 1953–1954 folio of six prints in a beautiful but inexpensive edition, published by the Marxist Masses & Mainstream Press. In the 1960s, he contracted with the black-owned Golden State Mutual Insurance Company of Los Angeles to illustrate their calendars in order to insure that his art would be found in black homes, restaurants, barber and beauty shops, and places where working-class blacks would see it, doing more than any other artist of his generation to put art in the hands of the black and white working class (Barnwell 2002, 84; Clothier n.d., vii).

White’s focus on ordinary people, on the black worker, and on black resistance was deeply bound up with his progressive political engagements. He wrote for and illustrated the

Daily Worker and the

Sunday Worker,

New Masses, and

Masses & Mainstream, all of which nurtured his developing political activism as well as his aesthetic formation. Along with his first wife, the renowned sculptor and artist Elizabeth Catlett, he taught classes at the communist-led Abraham Lincoln School in Chicago and at the Left-led George Washington Carver School for working people in Harlem. His international travels and interactions with the Left in Mexico, the Soviet Union, and Germany helped establish his international reputation. He studied art in Mexico with the Mexican communists Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and Jose Clemente Orozco

5 and in interviews, articles, and private conversations described those collaborations as important to his growth both as an experimental artist and as an

artist on the Left.

6 The first major critical study of his work by the communist critic Sidney Finkelstein was published in Germany by a socialist publisher. His major U.S. exhibitions in the 1940s and 1950s were at the left-wing American Contemporary Art Gallery, run by a left-wing director, Herman Baron. He met his second wife, the social worker Frances Barrett, at a camp for the children of the Left, Camp Wo-Chi-Ca (Workers’ Children Camp), where she was a counselor and he taught art, and when they moved to New York in the 1950s, he and Fran were active members of the Left-dominated Committee for the Negro in the Arts.

7 In short, in the 1940s and 1950s, the critics reviewing White’s work, the gallery showing his work, the publishers publishing his work, and the major biographer and critics commenting on his work were all Left-identified and nearly all aligned with the Communist Party.

While the institutional support of the Left was important in supporting an already formed aesthetic, White began, in the mid-1940s, to explore the formal techniques of modernist abstraction. Less than a decade later, as the mainstream art world shifted radically in the direction of abstraction, White embraced the socialist realism favored by Party art critics and turned away—at least during the period of the high Cold War—from his 1940s work, which had so effectively (and affectively) combined a politically charged realism with a degree of modernist experimentation. I believe that this shift precipitated a crisis for White and that, even as he appeared to be in close alignment with the Party’s views on art, that crisis was expressed in his work. In this chapter I look at how crisis is encoded in his art and try to assess the assets and liabilities of White’s long-term affiliation with the communist Left. With the help of the interviews White and others gave to Peter Clothier in the 1970s and 1980s, this chapter investigates, although inconclusively, how this combination of black cultural politics, modernist aesthetics, and leftist radicalism played out in White’s work and life.

The second goal of this chapter is to challenge those studies that omit, obscure, or elide White’s radicalism. I understand the black-Left relationship in White’s life (as in others) as a complicated one of support and conflict, anxiety and influence, love and theft, eventually resolved, at least partly, by White’s move to black cultural nationalism in the 1960s. I carefully examine the tensions that develop between White and the Left during the Cold War, as leftist art critics, contending with the repressions of the Cold War, became more rigid in their ideas of what constituted a progressive and politically acceptable art practice. To some extent, this sounds like an old tale of the decline of the Left and the subsequent turn of the black left-wing radical artist to black nationalist and civil rights movements,

8 a shift precipitated by what Richard Iton (2010, 33) describes as the Left’s “chronic inability to reckon with black autonomy.”

9 But White’s story is definitely not one of leftist manipulation and betrayal but a rarely told story of a highly nuanced, personally and professionally productive, sometimes difficult and vexed, but ultimately life-long relationship with the Left that was still vital when White died in 1979 in Altadena, California.

10AN ARTIST IN CHICAGO’S BLACK RADICAL RENAISSANCE

Born in 1918 in Chicago, the child of a single mother

11—White’s father, to whom his mother was not married, died when he was eight, and his mother divorced his stepfather when he was ten—White came of age in “Red Chicago” during the 1930s, when the Communist Party had developed a broad base and become an accepted organization in the black community (Clothier n.d., 6, 27). The Chicago community activist Bennett Johnson claims that “the two most important and active organizations in Chicago’s black community in the early 1930s were the policy racket and the Communist Party, the former taking care of black entrepreneurs and the latter taking care of the people who were buying the numbers.”

12 It is quite clear why the Party attracted blacks in Chicago, especially during the Depression. In an industrialized city, where blacks were at the bottom of industry’s discriminatory structures and were trying to organize themselves as workers, the militant efforts of the Communists to unionize, stop evictions, integrate unions, and give positions of authority to blacks in the unions were beacons of light to the African American community. Horace Cayton writes in

Black Metropolis, his sociological study of black Chicago, that in the 1930s when a black family feared an eviction, it was not unusual for them to tell their children to run and “find the Reds” (Storch 2009, 113).

13In one oral autobiography, White says that as a child he spent a great deal of time alone in the library, where he discovered the book that changed his life, Alain Locke’s 1925 anthology

The New Negro, which included hundreds of pages of literature by and about blacks, as well as black-and-white drawings and full-color portraits of famous black writers and activists.

14 Already a precocious artistic talent, White was taken with the visual aspects of this text, especially those “wonderful portraits of black people” by the German-born Harlem Renaissance artist Winold Reiss: “I’d never seen blacks quite that handsome. It blew my mind.”

15 Through

The New Negro he says he discovered an affirmation of both the tremendous artistic talent of black people and their inherent beauty and dignity. During his many solitary visits to the library, White also found a world of black poets, writers, and activists, including Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, Denmark Vesey, Nat Turner, and Phillis Wheatley, so when he encountered the total absence of any black historical figures in a history class at Chicago’s then mostly white Englewood High School, he was not only disappointed but confrontational. When he asked his white history teacher why these people were omitted from the history textbook, he was told to sit down and shut up (1955, 36). White experienced other incidents of educational racism; these became catalysts for his developing racial consciousness. His drama teacher told him that he could help with sets but that there were no acting roles for black students. When he was awarded two scholarships—one from the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts and one from the Frederick Mizen Academy—he was rejected by both institutions when he showed up in person to accept. All of White’s biographers remark on his deepening involvement in black cultural life, and these encounters with racism must be counted as a part of that development. Finally, through the help of one of his teachers, he applied for and won a full-tuition art scholarship to Chicago’s School of the Art Institute, where he was exposed for the first time to the formal art world (Clothier n.d., 17).

16If White’s black cultural consciousness is forecast in these school experiences, it was an alternative neighborhood school that directed him to the political and cultural Left. In 1933, when he was about fifteen, he saw an announcement in the

Defender for a meeting of the Art Crafts Guild of the South Side, but he was so shy he first had to walk around the block in order to get up the nerve “to go to these strange people.”

17 He finally knocked on the door and told them he wanted to join the art club—the Art Crafts Guild.

18 There he met what would eventually become Chicago’s black progressive art community. Led by the artists Margaret Burroughs and her future husband Bernard Goss, the Art Crafts Guild was a distinctively community-based group that included visual artists, sculptors, writers, and dancers, among them Charles Sebree, Eldzier Cortor, Joseph Kersey, Charles Davis, Elizabeth Catlett, George Neal, Richard Wright, Gwendolyn Brooks, and Katherine Dunham. With little money, the visual artists worked out a plan for Neal, the senior artist among them, to take classes at the Art Institute of Chicago and then come back and teach the group what he’d learned. When the Works Progress Administration (WPA) of President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal targeted the South Side of Chicago in 1938 for federal assistance to bolster the arts, Burroughs and Goss played a major role in the planning for a federally supported public center for black art that eventually became the South Side Community Art Center (SSCAC), which is still operative on Chicago’s South Side. The improvised studios and converted back-alley garages of the Art Crafts Guild were transformed into a South Michigan Avenue mansion, remodeled by architects and designers of the Illinois Art Project, allowing poor and struggling black artists to be supported, at least for a brief time, with federal dollars.

Though black left-wing visual artists are almost always pegged as social realists, Bernard Goss suggests that the SSCAC artists were self-conscious modernists from the beginning. In a 1936 essay, “Ten Negro Artists on Chicago’s South Side,” written for

Midwest: A Review, Goss writes that, having learned to read and write and to straighten our hair, and having discovered art schools, “We became modern.” In the attempt to represent this new culture, Goss says the group “practically all agree[d] silently on the doom of Conservatism.” A kind of artistic manifesto, the essay describes the SSCAC group as artists in search of “the identity of a new culture,” influenced by Africa, by continental Europe, by the Native American Indian, and, Goss adds, some of these new identities would be racial, some not. What they had in common was that all felt that modernism conferred upon them a sense of creative freedom, which Goss describes in terms that evoke the energy and play of childhood: “that consciousness [of modernism] gives us a greater space for romping than we had at the academic school” (18).

If the SSCAC was a wonderful social community, it was also radicalizing for White both politically and aesthetically. When he began to take part in the Negro People’s Theatre Group at the SSCAC, first by designing and building sets and later as an actor, he was already beginning to speak the language of a leftist radical. He wrote to the communist writer Mike Gold on December 28, 1940, asking Gold to include something about the “Negro in the Theatre” in his column in New Masses and sharing with Gold the difficulties of trying to build an interracial, mass movement theater:

We are trying to be a real people’s theater, but our greatest difficulty is in attracting a mass Negro and white audience…. We found that large numbers of Negroes really wanted to see the stuff that’s in the movies and wished to avoid having their problems as a minority group in this capitalistic world shown to them and solutions pointed out. Of course we were called radical and everything else. But our group of young people have grown to understand that these epithets are thrown at whosoever or whatsoever speaks for the working man.

(Clothier n.d., 38)

White was also beginning to paint in the style that would identify him as a man of the Left.

Fatigue or

Tired Worker, a Depression-era drawing completed in 1935, when White was only seventeen years old, shows a sleeping black laborer bent over a rough-hewn table, his weariness captured in the “shoulders hunched against a sharp concern,”

19 the furrowed brow, and his head resting heavily in the crook of his arm. The enlarged hands, which would become a White signature, the muscular shoulders and head, and the determined set of his mouth convey, even in sleep, both exhaustion and strength. The slight distortion of the natural figure indicates that White is already interested in adopting modernist techniques in his work, and, even more to the point, these expressive techniques enabled him to convey a deep sensitivity to the plight of the worker.

WHITE AND THE ILLINOIS WPA

For about three years, beginning in 1938, White worked on the WPA Illinois Fine Arts Project (WPA/FAP), moving between the Arts Section and the Mural Division of the FAP and studying Marx, Lenin, and Engels with his fellow WPA muralists, Edward Millman and Mitchell Siporin. With Millman and Siporin, he also studied the work of the radical Mexican muralists, another inspiration, particularly after White visited Mexico in 1946 and 1947, that drew him to the Left. Burroughs reports that while White worked with the WPA, he was a member of and attended meetings of both the Artists’ Union and the John Reed Club, an organization of left-wing writers and artists. White remembered that black artists easily qualified for a job with the WPA because they so clearly fulfilled the “pauper’s requirement” of being destitute: “You first went down to the Works Progress Admin. office. You declared yourself bankrupt, or destitute, I mean, and stated that you needed some economic aid…. They in turn, once having investigated and found this was true, then you were placed—they sought to place you on a job suited to your abilities and so forth.”

20 White’s most memorable WPA experience was the sit-down strike at WPA headquarters to protest the art supervisor’s refusal to hire black artists. Although the strike resulted in police intervention and arrests, it also spawned the formation of the Artists’ Union that White said eventually became very strong, and, in 1938, it formally affiliated with the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO).

21 According to the art historian Andrew Hemingway (2002), the leading figures in the Artists’ Union, which began as the Unemployed Artists Group within the John Reed Club in 1933, were Party members or fellow travelers, and, though their constitution claimed the group was nonpolitical, their public pronouncements about the solidarity between artists and workers, their class-inflected rhetoric about hope for a new world, and their history with the communist-aligned John Reed Clubs suggest otherwise. By this time White was seriously studying art and Marxism with Morris Topchevsky (Toppy) on the WPA and at Chicago’s Abraham Lincoln School (Clothier n.d., 47). What Burroughs and other leftists called “the defense of culture”—to preserve art for the people, not for the elite—became White’s mantra for the rest of his life, a commitment to a representation of black people that would counter the stereotypical images of blacks and that questioned their absence in art and to making art that spoke to and was available to the working class.

In 1941 White met and married Catlett, who had come to Chicago to study ceramics at the Art Institute and lithography at the SSCAC, and although Catlett claimed in an interview in 1984 that the communists in the SSCAC tried unsuccessfully to recruit her, she admitted to her most recent biographer that by the mid-1940s both she and White were working closely with the Party (Herzog 2005, 39). Their involvement in Chicago Popular Front organizations like the National Negro Congress (NNC), a communist-initiated organization active in Chicago; the then-progressive black newspaper, the Chicago Defender; the South Side Writers’ Group, founded by Richard Wright; and the Abraham Lincoln School, directed by the communist William Patterson indicates that the seeds of the couple’s commitment to progressive social issues and to an art focused on the black working class were nourished in these Negro People’s Popular Front collaborations, so aptly described by the cultural historian Bill Mullen as characterized by “an improvisatory spirit of local collaboration, ‘democratic radicalism,’ class struggle, and race-based ‘progressivism’” (1999, 10). White came of age in and was wholly at home with this brand of improvisatory, collaborative, community-and-race-based radicalism that allowed him to develop freely as an artist and as a political thinker.

As is true of the literary figures in my study, White’s associations with communism and the Left have been downplayed or ignored by his major biographers and by most literary and art historians, with the exception of Andrew Hemingway, whose comprehensive 2002 critical study identifies White’s communist connections (173). References to the Left or to the Communist Party in White scholarship are often filtered through the language of anticommunism. In White’s most recent biography, for example, the author Andrea Barnwell says of the Civil Rights Congress, a merger of the NNC, the International Labor Defense (ILD), and the Communist Party, that it was a “group

suspected of affiliating with the Communist Party” (2002, 44, emphasis added), that White continued working and collaborating with other left-wing artists “

despite the danger of being affiliated with progressives” (42, emphasis added), and that he “

sympathized with the Communist Party’s aims” (42, emphasis added), all of which suggest that White had only marginal and tenuous relationship to the Party.

In a 2008 interview, White’s close friend Edmund Gordon, professor emeritus of sociology at Columbia University, offered this carefully worded description of White’s leftist politics:

He clearly identified with the Left, though he never mentioned to me that he was a member of the Party. In those days you didn’t go around talking about being in the Party. I never saw a so-called Party card, but it was no secret that his politics were Left, and in his more candid moments, I am sure that he would say he believed in socialism. He certainly was very grateful to the Left for their support. When he went to Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union, I’m sure his support for that trip came from that source.

22

The commentary on White’s political radicalism suggests that, even fifty years later, White’s relationship to the Party can be constructed only as philosophical and ideological affinities but that any institutional or organizational relationship to the Party is still suspect and dangerous. Nonetheless, as with all the figures in The Other Blacklist, those institutional and organizational ties are critical for understanding the development and direction of White’s art.

THE 1940S MURAL:

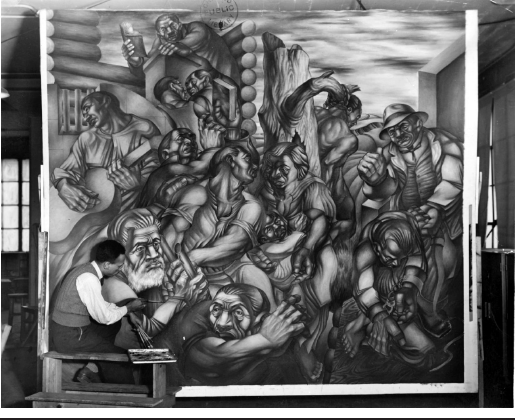

TECHNIQUES USED IN THE SERVICE OF STRUGGLEBetween 1939 and 1940, while working on the WPA, White completed three of his great murals, Five Great American Negroes (1939–1940), A History of the Negro Press (1940), and Techniques Used in the Service of Struggle (1940), all done as part of a progressive Popular Front agenda of expressing social-democratic ideals. But it was White more than any other progressive muralist who was devoted to inscribing black resistance in his representations of a democratic America. Besides embodying the ideals of the Black Popular Front, two of these murals—A History of the Negro Press and Techniques Used in the Service of Struggle—show White following the example of the Mexican muralists and the other left-wing WPA artists in combining formal experimentation with a vision of the black national history of struggle.

In contrast to the sense of relentless and progressive motion in

A History of the Negro Press, White’s other 1940 mural,

Techniques Used in the Service of Struggle, depicts black struggle checked by racist brutality.

Techniques was variously labeled

Chaos of Negro Life (Barnwell 2002),

Chaotic Stage of the Negro, Past and Present, and by White as

Revolt of the Negro During Slavery and Beyond. These conflicting titles reflect the way viewers, used to the more pacific WPA style, which generally represented an America of peace, progress, and prosperity and rarely included people of color or racial strife, may have been unsettled by this raw depiction of racial violence.

23 The thirteen figures on the panel constitute a historical tableau of both black subjugation and black resistance to slavery, peonage, sharecropping, and lynching. On the far right side of the left panel a black man, bent over almost to his knees, is held in shackles and chains by a white overseer, the only figures physically separated from the others.

24 Slightly right of center a lynched body hangs from a tree that surrealistically comes up out of the ground and is blasted off at the top, with its one branch curved around to the hanged man’s neck as if it has gone in search of him. In the center of the mural, as in several of White’s murals, there is a black family, with a woman holding a child and next to them the man of the family, looking back in anguish toward the woman, his arms stretched out in front of him. Next to him the enlarged head of John Brown, as if looming out of history, seems disconnected from Brown’s foreshortened arm, which holds a rifle and is intertwined with the hand of the black father. On the left side of the mural are figures that continue the theme of black resistance culture: a man with a guitar standing next to iron bars of a jail cell, who might suggest another leftist symbol, the folk singer Leadbelly, and another man holding up a book, a signature image White used to represent the power of literacy and education. At the very top of the triangular composition a man, perhaps a preacher, holding an open book at a lectern or pulpit, looks down angrily on two men who are turned toward each other with questioning and skeptical looks, as if dismissing the illusions of religion. The overall narrative depicted in the intertwined and intersecting bodies is that black progress has been blocked by the forces of racism, that in the face of massive racial violence, despite the “techniques of struggle,” there is no exit.

Source: Chicago Public Library, Special Collections and Preservation Division, WPA 132.

What makes White’s mural exceptional is the central place White accords black people and black resistance in the narrative and its unrelenting representation of racist brutality.

25 Even though in 1940 White had not yet traveled to Mexico,

Techniques demonstrates that the Mexican muralists’ focus on social and political justice and on indigenous people, achieved through formal experimentation had already begun to influence White. The artist and former White student John Biggers specifically cites the influence of Millman and Siporin

26—and through them, the Mexicans—on White’s work. Biggers thought that the work took on “a new abstract quality, a new kind of strength as a result of working with these two guys” (quoted in Clothier n.d., 14). Not only were the Mexican artists using their art to fight for the same progressive and radical values as the artists in White’s circles—against poverty, racism, and exploitation—but also, in their visions of a future, they featured indigenous blacks in prominent and powerful positions. While much of the influence of the Mexicans came to White indirectly through Siporin and Millman, we know through Burroughs and White that the political and artistic work of the Mexicans was discussed in African American community centers and that

los tres grandes (Rivera, Orozco, and Siqueiros) were well known in the United States. Let me point out that throughout the 1950s, White never visualized black resistance in such stark, defiant, and bitter terms as he did in

Techniques. As an example of “a marked increase of stylized features” (Clothier n.d., 60) in his work,

Techniques exemplifies the direction that would eventually precipitate a collision course with the Left and a clear shift away from stylization toward greater representational realism. During the 1940s, however, White continued to focus on black historical themes and to pursue the methods of formal experimentation that allowed him not only to craft a distinctive style but also to communicate through visual narratives of racial injustice the power, agency, and dignity of the black subject.

THE SOUTH, THE ARMY, THE HOSPITAL, AND THE MEXICAN EXPERIENCE

The six years of White’s life from 1943 to 1949 were emotionally tumultuous but professionally rewarding. In 1942 he and Catlett moved to New York, where they both worked at the left-wing George Washington Carver School in Harlem and, in the summer, at the leftist Camp Wo-Chi-Ca, founded by the Furriers’ Union for leftist workers and their families to support interracial cooperation. He continued his work as an editor for

Masses & Mainstream and the

Daily Worker. In 1943 he received a two-thousand-dollar Julius Rosenwald Fellowship, which he used to travel with Catlett throughout the South, “studying and painting the lives of black farmers and laborers” and visiting his extended family (Barnwell 2002, 29). He also intended to study in Mexico, but the draft board denied his request. In 1943 he and Catlett also went to Hampton Institute in Hampton, Virginia, where White completed the mural

The Contribution of the Negro to American Democracy, when he was still only twenty-five years old. In line with Popular Front politics, the mural represented a homegrown defense of American democracy made possible by black activism. As Rivera did with his inclusion of a picture of Lenin on his Rockefeller mural in New York,

27 White included a covert sign of his leftist politics. Along with the avenging black angel and revolutionary heroes Crispus Attucks, Nat Turner, Denmark Vesey, Sojourner Truth, Frederick Douglass, and the runaway slave Peter Still (who carries a flag with the words “I will die before I submit to the yoke”), White depicted the black left-wing National Maritime Union (NMU) activist Ferdinand Smith, who was eventually deported for his radical activism, and placed him next to Paul Robeson, whose arm, shaped like a powerful wooden mallet, completes the mural’s (and White’s) revolutionary designs.

White’s art-making came to an abrupt end when he was drafted in 1944. He served a year in the armed forces, where he contracted tuberculosis while he was working to stop the flooding of the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers; he then spent two years in a hospital in upstate New York. When he appeared to be recovered, he went with Catlett to Mexico to study and work with the Mexican artists. If the Mexicans had a powerful influence on White from several thousand miles away in the early 1940s, the year and a half that White actually spent in Mexico (1946–1947) invigorated that influence and accounts for the most politically charged and stylistically innovative art of his career. In Mexico, he says he felt for the first time in his life like a man who could go anyplace: “Nobody could care less what I looked like.”

28 During this time, White began to understand what he considered the major problem in his life as an artist: the dichotomy between his political ideals and his personal artistic goals. He thought that the Mexican artists, with their studios in the streets, had solved that problem:

So I saw for the first time artists dealing with subjects that were related to the history and contemporary life of the people. Their studio was in the streets, their studios were in the homes of the people, their studio was where life was taking place. They invited the Mexican people to come in to evaluate their work, and they sought to learn from the people…. They didn’t let their imagination run rampant. They solved the problem of this contradiction in a collective way. I saw artists working to create an art about and for the people. That had the strongest influence on my whole approach.

(Clothier n.d., 56)

The Mexican influence is especially evident in all of White’s 1949 drawings, which are more overtly political and stylistically more daring than his other 1940s work. The 1949 pieces in the 1950 exhibition at the ACA Gallery include portraits of four historical figures who were staples of leftist representational insurgency (John Brown, Frederick Douglass, Sojourner Truth, and Harriet Tubman) and three historical drawings (

The Ingram Case,

The Trenton Six, and

Frederick Douglass Lives Again or

The Living Douglass), which show that expressionistic techniques were becoming part of White’s stylistic explorations.

29 Let me describe two of the most well known of White’s 1949 expressionistic drawings.

The Ingram Case, which was reproduced in the

Daily Worker along with an article, “The Ingrams Jailed—America’s Shame,” focused on a prominent civil rights cause supported by the left-wing Civil Rights Congress. Rosa Lee Ingram—a widow, tenant farmer, and mother of fourteen children—and two of her sons were sentenced to death in Georgia in 1948 for the murder of their white tenant farm owner, who, she claimed, had sexually assaulted her. In White’s drawing Rosa and her two sons are behind massive bars, with Rosa looking out beyond the jail cell and her sons looking pleadingly toward her, one with his arm reaching over the head of his brother as if to try to touch his mother. Hands are prominent in this drawing. One son clutches the bars with both hands, but Rosa’s right hand reaches beyond the bars and is balled into a fist. Her other hand lightly touches the bar, and both arms are enlarged. The shadings of black and white on their faces emphasize both their blackness and their suffering, and the light from Rosa’s eyes suggests grief and weariness. The bars of the cell seem to be laid on the bodies of these three figures, both holding them in the cell and weighing them down. But the swirling black and white lines of the mother’s dress and her fists on the bars undercut the painting’s sense of desperateness and suggest the tenaciousness of Rosa Ingram’s fight to free herself and her sons. In response to public opinion about the harsh sentences, Mrs. Ingram’s sentence was later changed to life imprisonment. Civil rights groups from the mainstream Urban League to the left-wing Sojourners for Truth and Justice fought to free Ingram, and largely because of the efforts of the CRC, the Ingrams were eventually freed in 1959 (Horne 1988, 212).

In

The Trenton Six, done in black ink and graphite on paperboard, White features the six men who were accused of killing a white man in Trenton, New Jersey, and sentenced to the electric chair, despite a lack of evidence and proof of a frame-up and coerced confessions. Thirteen years after the near lynching of the nine Scottsboro men, the same antiblack mob violence prevailed in the northeastern city of Trenton. After the widow of the murdered man named black men as the killers, the

New Jersey Evening Times carried an editorial entitled “The Idle Death Chair,” as if black suspects automatically required putting the chair to use. Because of the efforts of the CRC and Bessie Mitchell, the sister of one of the framed men, the sentences were reversed by the Supreme Court and, in a second trial, four of the six men were found innocent. In the midst of her fight to free her relatives, when Mitchell was asked why she turned to a group as controversial as the Communist Party, she replied, “God knows we couldn’t be no worse off than we are now.” In the White drawing, Mitchell is the central figure, standing in front of a barbed wire fence that encloses the six men, her enlarged hands and massive arms in a gesture of protectiveness, power, and pleading. One hand points to the men behind the fence, allowing the viewer to move past Bessie to the men who face outward at nothing in particular, as though acknowledging the desperation of their situation. Bessie’s eyes are sad but determined, gazing upward as though she is capable of doing whatever is necessary to free her kinsmen. However conservative these techniques may have seemed to 1950s mainstream art critics smitten by abstraction, they represented a black avant-garde. Deployed in the service of black resistance and on behalf of left-wing causes, these images of white oppression, black anger, and leftist political agency constituted a modernist assault on the national imaginary of Jim Crow America.

A few mainstream art critics praised White’s work precisely because it combined a black aesthetic with stylistic experimentation. In the

New York Times review of his first one-man show in September 1947, White’s work was described with an emphasis on form: “He paints Negroes, modeling their figures in bold blocky masses that might have been cut from granite.” The reviewer also commented on the effect of merging stylized techniques with a black cultural sensibility: “Something of the throbbing emotion of Negro spirituals comes through. A restrained stylization of the big forms keeps them from being too overpowering. This is very moving work” (Horowitz 2000, 19). What White was doing in these 1949 pieces—combining stylistic experimentation with meaningful social content—was entirely consistent with the work and thinking of many socially concerned artists. According to the cultural historian Bram Dijkstra (2003, 11), these artists “link[ed] the technical innovations of modernism to a working-class thematic as part of a passionate commitment to the principles of social justice and community rather than to feed the indulgence of private obsessions.” By the early 1950s, however, critics on the Left began to assess the stylizations of White’s work negatively. Despite the fact that

The Living Douglass had appeared on the front page of the

Sunday Worker, Sidney Finkelstein, the major art critic of

Masses & Mainstream, found the piece problematically experimental, because, he said, the stylization of the human head and body “still lingers” (1953, 43–46), a clue that the winds of change were blowing and that White’s experimentations, no matter how much they throbbed with black emotion, would no longer find favor with certain Party critics. In these 1949 and 1950 drawings, black identity is represented as an aspect of historical narrative and therefore as contingent, open-ended, and mutable. In the portraits of blacks White would formulate after 1950, he made changes in both his style and his representations of black identity that correspond with the commentary of some leftist art critics in the

Daily Worker and

Masses & Mainstream. The result is a representation of blackness that is far less inventive and innovative than these dynamic 1940s combinations of black subject, black resistance, and modernist aesthetics.

THE COMMITTEE FOR THE NEGRO IN THE ARTS AND THE BLACK LEFT RENAISSANCE IN NEW YORK

The changes in White’s personal life in the late 1940s and early 1950s deepened his commitment to the Left. In 1946 he went through an acrimonious divorce from Catlett, who married the Mexican artist Francesco Mora, whom she met while in Mexico. White then returned to the hospital for another year of treatment for a recurrence of tuberculosis, and when Frances Barrett, the young counselor he had gotten to know at the interracial left-wing Camp Wo-Chi-Ca, came to visit him in the hospital, they struck up a friendship that eventually led to their marriage in 1950. In the love letters they wrote to each other before their marriage, there is evidence that their political commitments were part of what drew them together. Charlie wrote to Fran in 1950 that their “deep and tremendous faith in love, people, and Marxism” would be “a solid front” in their interracial marriage (Barrett-White 1994, 22).

Fran and Charlie moved to New York City in 1950 and, despite the looming McCarthy onslaught, became part of a dynamic world of leftist intellectual and political activity. White was an editor at

Masses & Mainstream and had already had two exhibitions at the ACA Gallery, both New York–based left-wing institutions. Major Left-led and Left-influenced unions like United Electrical, United Public Workers Association, the Furriers’ Union, and the National Maritime Union (NMU) were all located in New York. The communists Ben Davis and Peter Cacchione had been elected to the New York City council, and the communist Vito Marcantonio was a New York City representative to Congress. White worked openly on the political campaigns of both Davis and Marcantonio, donated his art to support their work, and was friends with major black left-wing figures like Paul Robeson, W. E. B. Du Bois, the CRC head William Patterson, and the NMU vice president Ferdinand Smith. Also headquartered in New York during this period were important and influential leftist publications like Adam Clayton Powell’s

People’s Voice, the Marxist journal

Masses & Mainstream, Robeson’s newspaper

Freedom, the communist newspapers

The Daily World and

The Sunday World, and black left-wing organizations like the Council on African Affairs, the CRC, and—most importantly for the Whites—the Committee for the Negro in the Arts.

During this period, which Fran White called “this CNA time” and “another Renaissance,”

30 the Whites made the decision to move from Twenty-Fourth Street to 710 Riverside Drive uptown because they wanted to be close to the black community and because “all the CNA activities [were] uptown.”

31 Founded in 1947 by Paul Robeson and others on the Left, with the goal of “full integration of Negro artists into all forms of American culture and combating racial stereotypes,” the CNA was a militantly black, politically Marxist, socially bourgeois, interracial cultural organization that was, perhaps, the most successful black/Left collaboration of New York’s Black Popular Front, though it is almost totally marginalized in leftist literature except for its venomous portrait in Harold Cruse’s 1961 critique of the Left,

The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual. Phillip Bonosky, a white communist who started the Harlem Writers Workshop at the request of black writers in CNA, remembers it as “our organization,” but CNA’s interracialism was certainly problematic for some. Some blacks felt that whites had no place in a black organization, and black women were often disturbed by the number of black men on the Left who were with white women (Barrett-White 1994). Nonetheless, the organization attracted a wide swath of black New York artists. The artist Ernie Crichlow was CNA chairman in 1950, and Elaine Jones, the first black timpanist for the New York Philharmonic Symphony, and Sidney Poitier were vice chairs (Barrett-White 1994, 57). Lorraine Hansberry reviewed CNA activities in

Freedom (May 1952), and

The Daily Worker provided extensive coverage of the CNA’s activities, including its founding conference and its annual Negro History Costume Ball, a public fundraising dance where attendees dressed as figures from black history. The Whites sold tickets to and attended CNA’s first theatrical production held at the Club Baron at 132nd and Lenox Avenue, featuring Alice Childress’s production of Langston Hughes’s

Just a Little Simple and two one-acts, Childress’s play

Florence and William Branch’s

A Medal for Willie. One photograph of a 1950s CNA event at the Manhattan Towers Hotel honoring black cultural activists shows an integrated crowd that demonstrates that during its short history (1947–1954), the CNA was a vital part of the New York Popular Front. Seated on the dais are the honorees Robeson and Du Bois; James Edwards, star of

Home of the Brave; Hughes, poet, playwright, and librettist; the actors Frank Silvera and Fredi Washington; Mary Lou Williams, composer and arranger; Theodore Ward, playwright; Janet Collins, dancer; Shirley Graham, writer; Lawrence Brown, composer; and Charles White, whose solo show at the ACA Gallery had closed in February of that year.

32 The CNA was not officially tied to the Party, but by 1948, when the attorney general targeted the CNA as a subversive organization, membership in the organization insured the blacklisting of several of its most famous members, including Poitier, Ruby Dee, and Ossie Davis and Harry Belafonte.

33

Source: C. Ian White and the Charles White Archives. © Charles White Archives.

Source: C. Ian White and the Charles White Archives. © Charles White Archives.

One of the reasons the CNA began to excite such interest in the 1950s was that the intimate and visual medium of television appeared almost simultaneously with the high Cold War and further exposed the extent of U.S. cultural apartheid and its profound exclusion of black artists. Fran remembered that when she and Charlie got the first television set and their friends gathered at their apartment to watch variety shows, their first reaction was a stunned awareness of the deliberately discriminatory policies of this new medium (Barrett-White 1994, 55–57). In a September 1949

Masses & Mainstream article, “Advertising Jim Crow,” which critiqued the advertising industry’s racist practices, the CNA writer Walter Christmas reported that in his informal two-week survey of magazines from the

New Yorker to the

Saturday Evening Post, he found “a strange world” being perpetrated in U.S. magazines, one in which the words “labor” and “poverty” were absent and where blacks appeared only as smiling servants or fearful African “natives.” Christmas also reported on a more systematic survey of the advertising industry done by the CNA in 1947, which estimated that of twenty thousand people in the industry, “exactly thirty-six were Negroes, for the most part used in minor capacities, mainly menial,” but never represented as part of American society. Negroes were “simply not shown as a part of American life,” never as “typical Americans” at town meetings, in crowd scenes, or even on Army recruiting posters (Christmas 1949, 55).

34LOVE AND RECOGNITION IN EAST BERLIN

In 1951, the CNA chose White to represent the organization at the World Youth and Student Festival for Peace in East Berlin as part of the Young People’s Assembly for Peace, which organized the “Friendship Tour” to Europe, where U.S. peace groups would meet with other labor and peace groups.

35 White was given a gala sendoff with a cocktail party hosted by the CNA on June 27, 1951, at the ACA Gallery on East Fifty-Seventh Street, and the CNA surprised him by raising the money to send Fran, who joined him in Paris. In the twenty-eight-page interview with Clothier in 1980, Fran White describes the tour in great detail, elaborating on the political as well as personal significance of the weeks they spent in Europe and the Soviet Union. The Friendship Tour was slated to begin in Paris and culminate in the Third World Youth and Student Festival in East Berlin, but at the Russian Embassy in France, the Whites were given visas and told mysteriously one night to get ready to board a train, which took them to Le Havre, where they were met by people who took them to a Polish steamship. On board were delegations from every country, including those of the Eastern Bloc. They were picked up in East Berlin, where the entire city was given over to this two-week festival. They met the “socialist leadership” from around the world, including the famous Turkish communist poet Nazim Hikmet. They were taken to see the camps at Auschwitz. Then, as mysteriously as the appearance of the night train, fifteen out of the forty members of the U.S. delegation, including the Whites, were chosen to go to Poland and Moscow. In Moscow, they were treated like dignitaries and given exceptional hotel suites filled with fruit and wine and chocolates. They toured farms, factories, the Bolshoi Ballet, music conservatories, art galleries, and art schools. Fran White says that they were treated “royally” in the socialist countries, where even schoolchildren talked about White’s work. They returned to the United States, she says in the Clothier interview, with a deepening understanding that to “bring socialism to the U.S.” would require “a social movement of the country and not just a few people with the ideas,” that it had to be understood as “shaped by the geography, history, and ethnic group of each specific country.” But they also faced criticism from those who “would battle him on socialist realism, because he did not find it ridiculous” (Clothier 1980–1981, 24). Fran emphasized they were both impressed with what they had seen in the Soviet Union. Charlie was especially taken with how ethnic groups were allowed to develop their own culture, and Fran was impressed by the Soviet treatment of children: “I don’t care what anybody tells me about socialism,” she reported. “The children were the happiest children that I’ve ever seen” (24). In the informal and free-wheeling atmosphere of the 1980 interview, Fran seems eager to express their elation over the enthusiastic embrace of White’s art in socialist countries, but in her autobiography, published fourteen years later in 1994, that respect and admiration for socialist politics is muted or absent.

The Whites’ European trip, which followed in the footsteps of Du Bois, Hughes, and Robeson, is essential in understanding the changes in White’s life, his art, and his political views after 1951. Gordon says he is quite sure that the trip was sponsored by the Left,

36 which accounts for the increased attention White received from the communist press when he returned to the United States. The trip also immediately triggered White’s FOIA file. In her autobiography, Fran says they were greeted at the airport upon their return by a summons to appear before the House Un-American Activities Committee and by a request from the State Department to surrender their passports. Within a few months the summons was unexpectedly withdrawn and their passports returned, but neither of the Whites was called to testify before an investigatory committee. Even so, an FBI informant kept close track of White’s activities on the trip, referring to him in one file as “Charles WHITE, colored, allegedly an American citizen” (U.S. FBI, Charles White, 100-38467-5) and carefully recording the public statements White made about his experiences at the World Festival, including his amazement at the friendliness of the youth of Korea and other socialist countries. White’s FOIA file also details his associations with Left-leaning or Left-led organizations, including

Masses & Mainstream; the New York Council of the Arts, Sciences, and Professions; the Jefferson School of Social Sciences; the George Washington Carver School in New York; the

Daily Worker; his support for clemency for Ethel and Julius Rosenberg; his attendance at a Cultural Freedom rally to protest the banning of the prounion film

Salt of the Earth; and his relationship with the ACA Gallery, adding that the ACA was “devoted to the work of socially conscious artists” (U.S. FBI, Charles White, NY 100-139770). According to the FOIA file, the Whites were followed closely in Moscow and were “seen at the Bolshoi Theater fraternizing with persons believed to be North Korean or Chinese Communists” (6. NY 100-102344). One section of his file, labeled “

AFFILIATION WITH THE COMMUNIST MOVEMENT,” summarizes all the reasons the FBI used to justify calling White a communist, including having “numerous books relating to Communism” and a sculptured bust of Stalin in his apartment, his “praise of Russia,” and “the predominant use of red in subject’s paintings” (NY 100-102344, 5). Unlike the files of Lloyd Brown and Alice Childress, a great deal has been redacted in White’s file, and the constant repetition of information and the FBI’s dependence on the

Daily Worker and

Masses & Mainstream for its reports suggest that there was little on White that could not be found in obvious and published sources. Whether or not the Whites were aware of this intense surveillance, the trip had a profound effect on White: in a speech at the Berlin Youth Festival, which was reprinted in the December 23, 1951,

Worker, White said, “I am 33 years old and I only felt the feeling of being a real man when I was in the Soviet Union.”

When Fran White tries to explain in her Clothier interview how this trip affected them both personally and politically, her statements are often contradictory, possibly an indication that even in the 1980s, their affiliation with the Left was still an area of anxiety. Clothier asked Fran about their relationship with the Party: “Party affiliation on return?” Reflecting her hesitancies, she answered both negatively and affirmatively:

No, we had been so close before the trip, yes, we wanted to bring socialism to the US. We realized in reality that it had to be a social movement of the country and not just true of a few people with the ideas…. All of the preaching and the literature was not going to make the change…. I think that when he came back was probably when he began to have differences with the communists that he knew (TOO SIMPLISTIC) [

sic] … you could sense that socialism was shaped by the countries, by the circumstances and the geography, the history, the art…. And then when he got home they [other abstract artists] would battle him on the socialist realism, because he didn’t find it ridiculous…. I think that was one of [Charles’s] main battles with the left movement, was that you don’t let the artist and you don’t let the black use their resources to determine the past.

(24–25)

Source: U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation.

FIGURE 2.5 (b). Page from Charles White’s FOIA file (c. 1951).

Source: U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation.

In this somewhat rambling but affecting narrative, Fran tries to describe an issue that plagued many black left-wing activists: How does one craft an independent black leftist politics within the larger, mostly white-controlled Left movement?

37 She says that they had been close to Party “affiliation” before the trip but that differences surfaced when they returned, with White battling the communists on one side—who, in Fran’s terms, were not allowing black artists like White to use their resources “to determine the past”—and his artist friends on the other side, because they found socialist realism “ridiculous” and wondered why Charlie didn’t. Fran’s response provides more evidence that White’s conflicts with the Party go back as far as 1951, even though his public statements at the time seemed totally in line with CP doctrine. Ultimately, Fran White’s interview reveals how unsettled White was both by the radical course he was taking by being openly identified with the Left and also by the Left’s refusal to let “the artist” and “the black” determine their own course.

38 When she says in the interview, “

so you’re not only touching blackness, you’re touching the Left” (27), Fran was describing poetically what she saw as the integration between White’s political ideals and his artistic goals. But she also put her finger on another aspect of conflict for a politically conscious black artist. During the McCarthy era, blackness—or black militant activism—could be considered synonymous with the Left and therefore discredited as “communistic.”

In contrast to Fran’s hesitancies, White’s description of the trip in his

Daily Worker and

Masses & Mainstream articles

39 was rhetorically and politically self-assured. He said that he began to feel a sense of agreement with other world artists that “the great forward-moving tide of art was realism,” despite what others were claiming as the “new.” As a result of this trip, he began to “see international questions as the primary concern of all people.” The American people needed to be able to identify with the African, Chinese, and Asian peoples, which, he said, was not only a theoretical issue for him but one that should be a part “of my actual painting and graphic work.” The “character and world view of the working class, its internationalism, and optimism” would now play a major role in his work. He said that hope must be revealed even in scenes “exposing the harshness of life of the common people.” Most importantly, White announced that he had now chosen “realism” as his guiding aesthetic. In a December 1951 interview in the

Daily Worker, he praised Soviet art as “the greatest in the world.” In one

Daily Worker installment, White continued to speak against “formalism,” Freudianism, and subjective art:

“There is no longer any problem of formalism in the Soviet Union,” said White. The Soviet artist stopped concerning himself with his inner emotions, with Freudianism, a long time ago. Today his work reflects what the masses of the people are struggling for. His primary aim as an artist is to “bring out in his work the whole feeling, aspiration and goal of the masses of working people.”

White continued with statements supporting socialist realism and the Party’s position against formalism:

“You can’t even conceive,” said White, “of an art that portrays a man like Stalin who is beloved by all the Soviet people, or an heroic woman like Zoya, in terms of planes, angles, and stylization, it would be atrocious and dishonest. Besides it would be impossible to bring out the heroism of Zoya and Stalin except through Socialist Realism.”

(Platt 1951b)

What ultimately encouraged the Soviet artist to reject formalism, White declared, was the close contact between the artist and the people: “All his assignments come from the people. When a piece of sculpture is commissioned for a factory and the factory workers don’t like it, they let the artist know about it real quick and he has to give it another reworking.” Later, as we will see from White’s statements in the 1970s, he would seriously question the idea of an artist being tethered to the will of the people.

White made these statements, which aligned him with communist aesthetics—specifically with the more rigid cultural policies adopted under the hard-line Zhdanov

40 phase—at a time when he had achieved something of a name for himself in the U.S. art world. By 1952 his ACA opening had been favorably reviewed in the

New York Times, he was the first black artist to exhibit on Fifty-Seventh Street, he was awarded a grant from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and his painting of

Preacher had been bought by the Whitney Museum for its permanent collection. He had produced stunning WPA murals for black colleges and universities, mounted exhibitions at galleries and universities all over the country, and had several solo exhibitions at the ACA gallery in New York. What is clear from all his narratives about his trip is that partly because of his relationship to international communism, White felt, quite accurately, that for the first time in his artistic career he had been given the kind of recognition that black artists rarely received in the United States in the 1950s.

41 He returned to the United States with “a bound volume of some of his works in hand and told a friend, ‘they sure know how to put things together.’” It was, his friend and writer Douglas Glasgow commented, a “marvelous experience for him in the sense of that kind of recognition,” a recognition clearly enabled by his affiliations with the Communist Left.

42IDEOLOGICAL REPRIMANDS AND AESTHETIC CORRECTIONS

White’s growing stature in the art world was accompanied by close attention from critics on the Left. That attention was positive through the 1940s, but by the late 1940s and early 1950s, the Party began to change its position on visual aesthetics. By 1945, under the leadership of William Z. Foster and under the pressures of Cold War, a besieged Party, no longer willing to pursue the flexible strategies of the Popular Front, returned to the hard-line position that “Progressive art today, inside and outside the Soviet Union, is that of social realism.” The term “realism” became ubiquitous in Party criticism in the 1950s, taking on the power of a revolutionary rallying slogan even as it remained a vague and elastic aesthetic concept. A “realistic” art pitted the Left against what was considered the “antihuman” formalism of the avant-garde, which included any kind of stylized art, abstraction, or expressionism. For the Left, the geometrical figures, vague curving shapes, and smears of paint from the abstractionists were a form of militant self-aggrandizement, a set of formal gimmicks devoid of social thought or purpose and designed to appeal to the elite, a form of pessimism that would make the individual feel helpless. Progressive artists, on the other hand, were encouraged to build up “strong hopes for the working class and present the everyday life struggles of working people. The human figure should be represented in a recognizable form as a means of conveying inspiration and hope, not for expressing personal idiosyncrasies.” The term that would encapsulate these principles was “socialist realism.”

43As White began to change his style, leftist art critics questioned his former tendency toward abstraction and applauded his move toward social realism. In his review of a 1951 show at the ACA Gallery, the African American art critic John Pittman singled out White for avoiding “empty abstractions” and showing pride and confidence and honest directness of the worker” and specifically named White’s art “socialist realism” (1951). The view that White’s work before 1950 had become unacceptable surfaces in a “Symposium on Charles White,” a 1954 meeting of the Voks Art Section in Moscow, March 18, 1954, reported on in

Masses & Mainstream. One commentator, D. Dubinsky, an engraver, praises the 1954 portfolio but issues a stern warning about White’s “shortcomings,” which are, in his view, White’s failure to represent a figure realistically. In 1955, the communist art and music critic Sidney Finkelstein, perhaps the single most important promoter of White’s early career, published (in German) the first full-length critical study of White’s art,

Charles White: Ein Kunstler Amerika, with forty-three illustrations covering the 1940s and 1950s up to 1954. While Finkelstein celebrated White as an exceptional artist, he used the text to document the communist requirements for a “realistic” art. In his articles in the left-wing press of the 1950s and in his book, Finkelstein critiqued the mural

Techniques Used in the Service of Struggle as too experimental, demonstrating the antimodernist position the Party would adopt in the 1950s.

44 Finkelstein admitted that he objected to this mural because of what he called the contradiction inherent in a style that conveys “high tension and excitement,” which makes it “more difficult to disclose the inner sensitivity and psychological depth of the human beings who are the subject” (1955, 23–24). What precisely constituted “inner sensitivity and psychological depth” remained subjective and oblique.

Similarly, White was praised by Charles Corwin, the

Daily Worker’s in-house art critic, as a progressive social artist. Then, in the middle of his February 20, 1950, review of White’s show in the

Daily Worker, Corwin inserted a paragraph that began ominously: “We have several suggestions we would like to offer White, even as we applaud the correctness of his basic orientation.” What follows is a list of corrections to White’s departures from approved models of social realism. The flat, angular lines of White’s figures, says Corwin, are “cold,” and there is danger that his style may become “static” and meaningless. Corwin continues: “In many the characteristic mood is a tortured repose with upturned eyes and furrowed brows,” and there is a danger of the picture being animated with “superficial devices.” It is difficult to ferret out the covert meanings of Corwin’s critique because its political and ideological undercurrents obscure what is ostensibly an aesthetic evaluation. What Corwin admits only obliquely is that this “corrective” is an attempt to influence artists who have strayed from the righteous path of socialist realism into the temptations of formalism.

In their campaign against abstract art, Party art critics—Corwin, Finkelstein, and, occasionally, the African American critic John Pittman—maintained an especially vigilant eye on White. In their comments about his work, these critics deliberately tried to direct White away from experimentalism toward realism. That pressure is particularly evident in their assessment of the drawings of Harriet Tubman and Sojourner Truth that White created between 1949 and 1951and illustrates what was being encouraged by the art critics in the

Daily Worker in the Cold War climate of the 1950s.

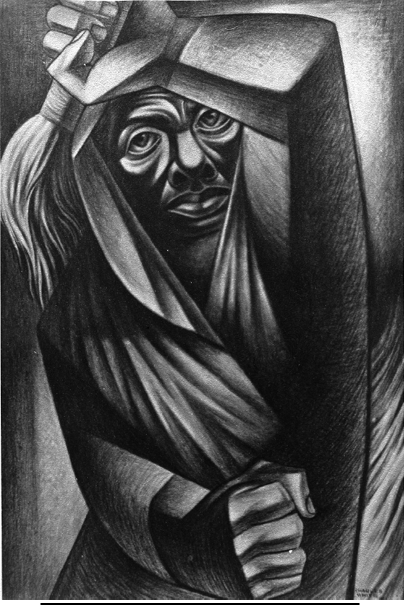

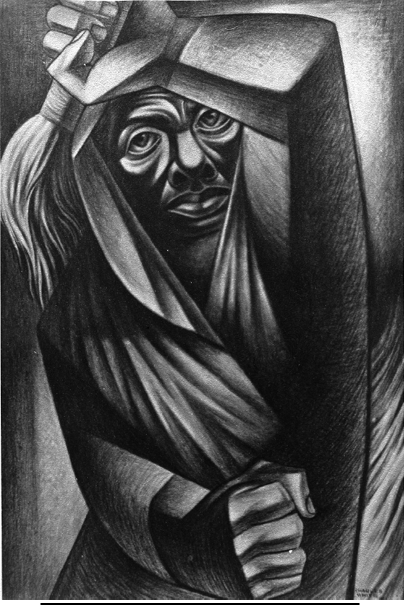

45In White’s

Sojourner Truth, there are still traces of cubist influence in the enlarged hands that seem sculpted into blocks of wood. The figure’s right hand is curved in the direction of the viewer as if in warning or self-protection; the eyes are illumined. Her left hand is raised, carrying White’s signature torch (or whip), and both arms and hands are shaped like wooden mallets. Here Truth is an enigmatic figure, who might be male or female. Her face seems to emerge from her draped robe, making her seem mythical and mysterious, an avenging Old Testament prophet. The look on her face is elegiac, and her eyes are large, stern, and sad. Writing in the 1951

Daily Worker, Corwin found an image like this unacceptable, because of what he claimed was its

unreadability: he called the 1949 cubist-style figure of Harriet Tubman, which is similar to the Truth drawing, “unapproachable,” “almost mystical,” and “God-like,” revealing, perhaps, his discomfort with her power.

Source: Photograph by Frank J. Thomas, Courtesy of the Frank J. Morgan Archives.

Source: Photograph by Frank J. Thomas, Courtesy of the Frank J. Morgan Archives.

In contrast, in

Exodus 1 Black Moses, the 1951 Tubman is clearly female, with shortened though still stylized hair, her hand raised and pointing the way to freedom for the group of black people following her. Comparing this to White’s 1949 Tubman, Corwin says, “The austere, the enigmatic, the depressed are replaced by a courageous optimism and confidence.” This “approved” Tubman seemed to alleviate Corwin’s anxieties and tensions created by the earlier one. The face is softer, there is the hint of a smile, and her place at the forefront of the group and her enlarged head suggest the movement toward victory, as does a man in the background with his arms upraised. Because the face of this Tubman is more “realistically” drawn, the mysteriousness and ambiguity of images like the first Tubman and the Sojourner Truth are replaced by a triumphant image of the

Moses of her people, a figure of comfort rather than of confrontation. For Corwin (1951), the elimination of any signs of abstraction was proof of the efficacy of the Left’s corrections and of White’s artistic maturity:

White has grown much during these past twelve months, and it is in just those elements which were most criticized a year ago that White has made the most evident advance. White’s subjects are again from Negro life and history, but they are more than just descriptive, for the monumentality of White’s forms, allied with the style of the Mexican social painters, transforms his subjects into large symbols of oppression, the struggle and the yearning for freedom of the Negro people. There was earlier a tendency for these monumental symbols to become formalized and static. During the past year, however, White, by humanizing his forms and clarifying his content is succeeding in giving human substance to his symbols.

(Corwin 1951, 11)

By the time he exhibited the third Harriet Tubman in the 1954 ACA Gallery show, White had created an image shorn of most of his experimental techniques, now taking what he called the

path to realism, which meant representing the human figure as anatomically “correct,” without expressionistic distortions. This 1954 Tubman image attempts to portray the socialist ideals of optimism and “hope for the future” rather than the bleak realities of segregation and racism evident in earlier drawings like

The Trenton Six and

The Ingram Case or in the earlier Tubmans. The hands are no longer the enlarged, geometric forms that resemble weapons. The eyes have a penetrating look but are not distorted. Standing next to Tubman is Sojourner Truth, who is shown in profile. Both figures wear the determined look of freedom fighters. Their beautiful and serene faces are familiar and recognizable. The suggestion of judgment, of warning, of blame in the 1949 Tubman and Truth is gone, as is what Finkelstein (1953, 20) called the “high tension and excitement” that he thought made it “more difficult to disclose the inner sensitivity and psychological depth of the human beings.” While the “approved” Tubman is accessible and inviting, the “tension and excitement” of the experimental Tubman and Truth, contrary to Corwin and Finkelstein, is both revolutionary

and modern.

In the veiled statement he issued to other progressive artists who were dallying with experimentalism, Corwin used White as both a model and a warning: “The steps which Charles White has taken this year towards the often stated ideal of social realism makes this exhibition a valuable object lesson to progressive artists and public alike as well as a very pleasant experience” (1951, 11). White seems to have been deliberately singled out to be an example. In the Corwin articles from February 1950 to March 1953, White was presented as an artist tempted by the sirens of abstraction, who, after accepting this critical advice, reaffirmed his commitment to politically approved artistic practices.

White’s former student, the artist John Biggers, like many of White’s artist friends, was both dismayed and perplexed with this turn toward realism: “It was almost as if he was working backward into the future … the early work with its marvelous abstract qualities … was so magnificent, he left that and went back into realism. I don’t know what caused this.”

46 As White himself knew only too well, the black cultural and social world was neither immune from nor unprepared to deal with the anxieties of the modern world, but he chose, at least for the brief period of the high Cold War, to work in the socialist realist art tradition, which favored those representations of black subjects that were recognizable and optimistic, rather than the dynamic, multifaceted, and psychically complex

modern people and communities White encountered in both Chicago and Harlem. As we will see later, this period produced a profound crisis for White, but it also produced portraits of black life more complex and interesting than they seem at first glance. What I want to tease out in the next section of this chapter is the way in which the 1953–1954 portfolio reveals White’s unease with the Party’s attempts to control the direction of his art and the covert resistance he employed in his art to forestall that control.

47THE 1953–1954 PORTFOLIO: BLACK ARTIST IN UNIFORM?

By the time

Masses & Mainstream published the 1953–1954 portfolio,

The Art of Charles White: A Folio of Six Drawings, White’s radical departure from his earlier experimental art seemed complete. There are at least two explanations for the changes. One is that these changes were aligned with the views of art critics in White’s left-wing circles, and the other is that these changes reflected White’s own desires for an art that would reach ordinary people and that he could best reach that audience through realism. White’s friend Bill Pajud, the art director at the Golden State Mutual Insurance Company, explained that the reason White’s art was chosen for the Golden State calendar was that “Charles was the one black artist I knew who was literal enough in his drawing to be accepted by people who had not any aesthetic appreciation” (Clothier 1980–1981, 62). The portfolio of six black-and-white lithographs was sold through subscription for three dollars and through bookstores and art shops in large (13" x 18"), ready-to-frame prints, with the goal of making art available to working-class audiences, “who are usually unable to afford such art.”

48 The six drawings—

The Mother,

Ye Shall Inherit the Earth,

Lincoln,

The Harvest,

Let’s Walk Together, and

Dawn of Life—were introduced by leftist art critics, who framed the folio in almost exclusively political and nonaesthetic terms.

49 In the preface to the portfolio Rockwell Kent says that the lithographs actually transcend art and embody “peace, love, hope, faith, beauty, and dignity.” In the first of two

Masses & Mainstream articles on the portfolio, “Charles White’s Humanist Art,” Finkelstein equates White’s shift to realism with “love for the working people.”

50 In “Charles White: Beauty and Strength,” the artist Philip Evergood is the only Left critic to comment on the technical aspects of the portfolio drawings, but he too sees their major achievement as the production of “happy, hopeful faces” that can “counteract the fears, the uncertainty which are to be seen in so many faces everywhere around the world today” (1953, 39). Except for the portrait of Lincoln, the drawings in the portfolio represent workers and the working class, stoic in their dignity: a mother in farm clothes carrying an infant in

Ye Shall Inherit the Earth; two muscular farm workers, both intently focused on the job ahead of them, in

Harvest Talk; a young girl in

Dawn of Life, her hands held up prayerfully as she releases a white dove into the sky.

The Mother shows only the face and hands of a middle-aged woman, her enlarged hands covering nearly a third of her face and folded around a cloth as if in prayer. The weary lines around her eyes and her half smile portray the endurance of a woman who has known and survived hard times.