America in 1956, baby…. Communist? Black? You only needed to whisper it once.

—SARA PARETSKY, BLACKLIST

We are all going to suffer much more until we wake up and defend the rights of Communists.

—ALICE CHILDRESS, CONVERSATIONS FROM LIFE, 1952

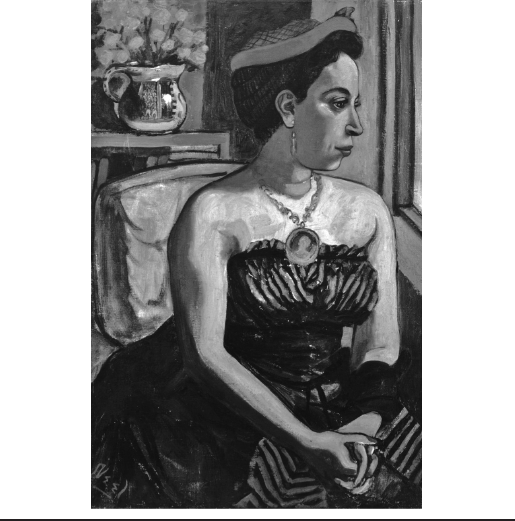

IN 1950, WHEN Alice Neel, a well-known visual artist and a publicly involved communist, added the writer Alice Childress to her portraits of communists, nearly all of them white and male, she was acknowledging Childress as one of the most important left-wing women of the 1950s (Allara 2000, 112). Neel’s portrait of Childress is almost completely unknown, but it is one of the clues that I have followed to uncover Childress’s leftist identity, and I return at the end of this chapter to speculate on what it reveals about Childress. Despite her fairly open traffic with the Left, including the Communist Party, Childress has almost never been considered in the context of the organized Left.

1 Unlike her literary Left counterparts Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, and Langston Hughes, all highly visible in black literary and Left studies, Childress, who remained openly connected to the Left throughout the Cold War and for six decades produced an aesthetics that reflect her radical politics, has only recently been included, though still only marginally, in postwar African American literary canons, and never as a radical leftist.

2

Yet from 1951 to 1955, the period of the high Cold War, she contributed a regular—and, in some instances, procommunist—column to Paul Robeson’s international-socialist newspaper

Freedom, maintaining close ties with Robeson even when many others were running fast to distance themselves from him. Her radical musical

Gold Through the Trees, performed at the left-wing Club Baron in 1952, was infused with the Harlem Left’s international consciousness, which asserted a relationship between U.S. racism and colonialism.

3 Her 1955 Obie-award-winning play

Trouble in Mind, though it was produced in the mainstream theater, is permeated with images of the blacklist. Blacklisted herself by 1956, Childress appealed to her friend, the top communist Herbert Aptheker, who helped her publish her novel

Like One of the Family with the pro-communist International Publishers. Even the plays and novels she published between 1966 and 1989 continue that radical perspective, though in more nuanced and subtle forms. Her 1966 play

Wedding Band, produced off-Broadway in 1972 and then as a primetime special on ABC in 1974 (starring the acclaimed Ruby Dee), critiques conservative notions of race and integration that had infiltrated black culture during the Cold War 1950s, as we saw in the 1950

Phylon symposium. In

A Hero Ain’t Nothin’ but a Sandwich, a 1973 novel about a thirteen-year-old heroin addict, which became a feature film in 1978 starring Cicely Tyson and Paul Winfield, the historical figures cited as models for the young main character are Marcus Garvey, Paul Robeson, Harriet Tubman, Malcolm X, W. E. B. Du Bois, Martin Luther King—and Karl Marx. Childress’s final two novels, one in which the Left figures prominently as part of the main character’s political education and the other structured by Cold War imagery, show the continued importance of the Left in her work. Highly reticent about her affiliations with the Left, Childress’s fiction, drama, and essays—and her extensive FBI file—constitute the only record we have of an extended relationship between a black woman writer and the organized Left.

Source: U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation.

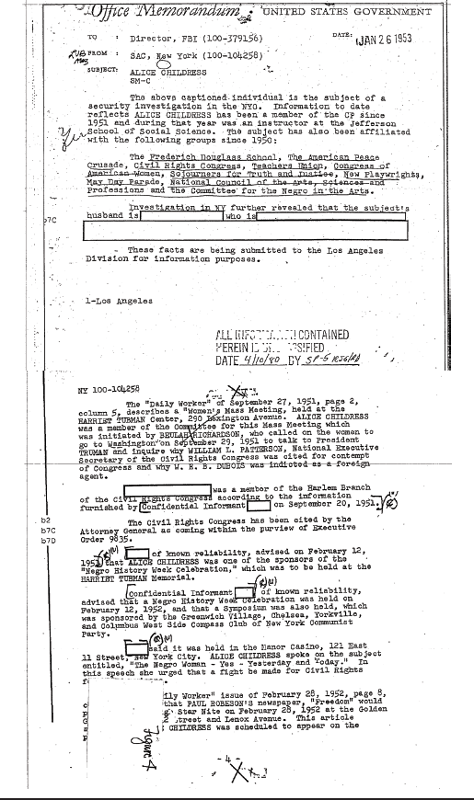

CHILDRESS’S FOIA FILE AS LITERARY HISTORY

While Childress was evasive about her left past, her FOIA file is unambiguous. Far more enterprising and thorough than most literary historians, the “confidential informant of known reliability” reported carefully on Childress’s political activity from 1951 to 1957, even offering some analyses of Childress’s literary productions.

4 We learn from her FOIA file that Childress taught dramatic arts at the communist-influenced Jefferson School of Social Science; spoke at a rally for the blacklisted Hollywood Ten in 1950; walked in the annual communist May Day Parade; sponsored a theater party to benefit the progressive United Electrical Workers Union; joined the campaign to repeal the Smith Act; entertained at an affair given by the Committee to Restore Paul Robeson’s Passport; sponsored a call for a conference on equal rights for Negroes in the Arts, Sciences, and Professions; raised money “for the benefit of the South African Resistance Movement”; and was one of the founders of the Sojourners for Truth and Justice, a movement for Negro women against lynch terror and the oppression of Negro people—all of which were designated “subversive” activities by the FBI (Goldstein 2008). The agent/informer reported on Childress’s publications in

Masses & Mainstream, the

Daily Worker, and

Freedom, and on her work with the left-wing Committee for the Negro in the Arts, an organization Childress helped initiate. The institutions that Childress was closely associated with during the fifties—

Masses & Mainstream, Club Baron, the Jefferson School of Social Science,

Freedom, Sojourners for Truth and Justice, the American Negro Theatre, the Committee for the Negro in the Arts—constituted a major part of the Harlem Left, a cultural front that shaped Childress’s personal and public life and continued in Harlem throughout the 1950s, long after the “official” Popular Front was considered dead.

5There are conflicting accounts about Childress’s relationship to the Communist Party (CPUSA), and her official membership in the Party cannot be verified with any certainty. In 1950, the FBI identified her as a member of the Harlem Regional Committee of the Communist Party. But, according to her friend Lloyd Brown, an open communist in the 1950s, Childress tried to keep her left-wing affiliations hidden so as not to handicap herself as a writer and as an actor, and he believed that Childress deliberately refused to join the Communist Party, “making it a point to be a nonmember who could do as she pleased” (phone interview with the author, October 2002). Another source (Sterling 2003) says that Childress actually was a Party member and that she attended Party meetings in a unit in New York with his wife, an actress. The cultural historian James Smethurst (2012) offers this explanation for the ambiguousness of Childress’s CP connections: “Another reason Childress might have remained a non-member in the 1950s is that the infrastructure of the CP in Harlem was in great disarray due to the effects of McCarthyism, factional infighting, and a number of leaders going underground. Some members of the Harlem section of the CP said it was hard even to find a representative to whom you could pay your Party dues.” Childress’s writings leave a number of clues that she was familiar with and may have been a part of the Party in Harlem, and Lloyd Brown maintained that there were only “technical differences” between Childress and Party members: “She was with us on all important issues” (2002). Whatever her official status with the Communist Party, Childress did not acquire her FOIA file and her leftist credentials by shadowing Robeson, as some critics have suggested, but because of her own extensive, well-earned political résumé (Harris 1986, xxvii).

RECONSTRUCTING CHILDRESS’S LEFTIST PAST

When critics rediscovered Childress in the 1980s, she seemed to be retrievable only within the boundaries of race and gender, neatly confined to the categories of “liberal,” “feminist,” “race militant,” “didactic black activist,” even “sentimental realist” (Harris 1986; Jennings 1995; Schroeder 1995, 334). One writer, improbably, accounts for Childress’s devotion to working-class characters as the result of her modest beginnings as a self-supporting high school dropout—all of which are accurate, if limiting, descriptions. In groundbreaking biography of Childress, La Vinia Delois Jennings does not mention Childress’s left-wing politics, but even in the 1990s, very little had been documented about Childress’s political leftist past.

6 Thus it is understandable that in her analysis of Childress’s 1952 play

Gold Through the Trees, which is virtually a textbook of 1950s Harlem leftist politics, Jennings (1995, 5) attributes the play’s political viewpoints to Childress’s “personal encounters with racism in America and her heightened sensitivity to apartheid in South Africa.” What we know now is that the play was produced in leftist venues (Club Baron), that it was reviewed in left-wing papers (

Daily Worker), and that its anticolonialist and antiracist themes were hallmarks of the black Left. The signs of the Left in Childress’s play

Trouble in Mind, which was produced in the midst of the high Cold War, are more difficult to detect, a sign that Childress’s leftist politics were a growing liability and that she was savvy enough to employ camouflage. The play’s racial issues—the 1955 Emmett Till murder and “the turbulent civil rights movement” (27) took center stage for most critics, but images of the HUAC and McCarthy investigations are woven throughout and structure the entire play. In her 2006 introduction to Childress’s novel

A Short Walk, which she wrote after Childress’s relationship to the Left had been fairly well documented, Jennings describes Childress’s early writing career as “concurrent with the early years of the United States’ civil rights movement, the black liberation movement, and the women’s liberation movement” (6), thus omitting the entire leftist context for the work Childress produced from 1949 to the 1960s.

If Childress’s left-wing politics are hard to pin down, some of the blame can be laid on Childress herself. She began revising her personal history with several autobiographical essays written in the 1980s, specifically a 1984 essay “A Candle in a Gale Wind.” In this essay she constructs herself as a loner, inspired to write about the masses because of her own personal experiences and determination, citing slavery, racial discrimination, her family and personal history, and her self-determination to explain her proletarian concerns—with no reference to the Harlem Left or Karl Marx.

7 She says she moved beyond “politically imposed limitations,” teaching herself to “break rules and follow my own thought,” which may be an indirect reference to her ability to resist both Party ideology and the conservative mainstream. Although there is an oblique reference to McCarthyism in her admission that she was subjected to “a double blacklisting system,” she maintains throughout the essay the pose of embattled loner, declaring that “a feeling of being somewhat alone in my ideas caused me to know I could more freely express myself as a writer.” She explains her affinity for “the masses” as a totally apolitical attraction to “losers”: “I turned against the tide and to this day I continue to write about those who come in second or not at all—the four hundred and ninety-nine and the intricate and magnificent patterns of a loser’s life.”

8“A Candle in a Gale Wind” is a far cry from Childress’s earlier essay “For a Negro Theatre,” first published in the Marxist journal

Masses & Mainstream in February 1951, then reprinted with an enhanced Marxist title in the communist

Daily Worker as “For a Strong Negro People’s Theatre.” Written and published during her years working at the American Negro Theatre, this essay represents the closest Childress ever came to a public declaration of her leftist identity. Not only does Childress’s title mimic the ways that the term “the people” was used by radicals in the 1930s and 1940s to signify the working classes,

9 but the

Daily Worker reprint is accompanied by a professionally done head shot of the glamorous thirty-something Childress that suggests she must have been comfortable being published in a communist-identified venue. The essay also reveals the always evident hesitancies and fissures in Childress’s relationship with the Left, which she believed helped her maintain the political and artistic independence. She says in the essay that she came to accept the notion of a “people’s theatre” after a “heated discussion” with the black radical left-wing playwright Theodore Ward, with Ward arguing that there was a “definite need for such a theatre” and Childress, despite her own long relationship with the American Negro Theatre, expressing the fear that a separate theater for Negroes might become “a Jim Crow institution.” That she was never entirely comfortable with the discourses of the Left becomes clear as the essay sets forth her own distinctive brand of black-centered left radicalism. Without committing to Ward’s vision—she agrees only that she “understands” his position—Childress proposes a “Negro people’s theatre” that will first of all combat the racist practices of mainstream theater: black students limited to “Negro” roles, white students never asked to perform black roles, black culture and history ignored, American blacks denied access to their African heritage, only those techniques developed by white artists recognized—a catalog that leads her to hope that a people’s theater will devote serious study to “the understanding and projection of Negro culture.” Her vision of this new theater is multicultural, black-centered, and internationalist: it will, she says, be concerned with the world and possessed of the desire “for the liberation of all oppressed peoples.” The “Negro people’s” theater will take advantage of “the rich culture of the Chinese, Japanese, Russian and all theatres,” and it will study “oppressed groups which have no formal theatre as we know it,” because, she says, “

We must never be guilty of understanding only ourselves” (63).

What makes the essay so important is that it shows Childress in the process of adapting and revising the cultural and political imperatives of the Left, something she would do for the rest of her creative life. Childress envisioned her audience as a politically sophisticated black working class: “domestic workers, porters, laborers, white-collar workers, people in churches and lodges … those who eat pig’s tails, and feet and ears … and who are politically savvy enough to watch to see if some foreign power is worrying the rulers of the United States into giving a few of our people a ‘break’ in order to offset the propaganda.” For Childress, “

the people” was a racialized “

my people,” a phrase that, in the more doctrinaire period of the 1930s, might have earned her a reprimand for putting race before class solidarity. Departing even further from the Left’s working-class emphasis, Childress also claims as “her people” those who drink champagne, eat caviar, and wear furs and diamonds with a special enjoyment “because they know there are those who do not wish us to have them.” Childress’s brand of radicalism did not separate her from the fur-wearing or fur-aspiring black middle class because her experience of U.S. racism was more deeply felt than interracial class solidarity. At one of the CNA’s writers’ workshops, when Paul Robeson suggested that Childress might improve a story about black workers by bringing in a union, she told him she couldn’t make that story believable because she didn’t know of any unions fighting for the rights of her people (Bonosky 2009, 34). In a letter she wrote to Langston Hughes in 1957, Childress took Hughes to task for his stereotyping of the black middle class as “snobbish strivers” and told him that she could very well “do without” his radical Left poems like “Move Over Comrade Lenin” and his “strained reference[s] to the ‘workin’ class,” because they did not ring true to her as a “real reflection of Negro life” (Childress 1957).

10Yet Childress’s racialized radicalism did not separate her from leftist radicals or from interracial work. The models she cites for this new theater at the end of her essay were three of the most radical cultural groups of the 1950s, all of which she was involved in—Harlem’s Unity Theatre, the CNA, and the interracial New Playwrights theater group (where Childress was a board member), formed by the communist Mike Gold, the blacklisted screenwriter John Howard Lawson, and the left-wing writer John Dos Passos, the latter two organizations listed prominently on the FBI’s Security Index.

Given the evidence of Childress’s close ties to the Left and to the Communist Party, I use this chapter to reread her literary, cultural, and political work to show how her idiosyncratic radicalism allowed her to incorporate black cultural traditions and a critique of race, gender, and sexuality with the radical international-socialist views of the Harlem Left. If Ralph Ellison used his writings in the Cold War 1950s to “wrestle down his former political radicalism,” as Barbara Foley (2010, 2) argues, Childress was wrestling in the opposite direction, moving from the more overt social protest of her early radical work to the subtle and complex leftist sensibility most evident in her 1966 play

Wedding Band. As I show in

chapter 1, the 1950

Phylon symposium’s dismissal of protest writing and its efforts to exclude blackness and race issues as not sufficiently universal gained traction in the 1950s under Cold War conservatism. Childress’s black internationalism and black radicalism was deployed to repudiate those restrictions, allowing her to explore more expansive and complex ways to represent black subjectivity, an example of what Alain Locke meant when he claimed during his short-lived radical period that “a Leftist turn of thought” can produce “a real enlargement of social [and I would add

aesthetic] consciousness” (quoted in Wald 2001, 277). I trace the development of Childress’s social and aesthetic consciousness, first through her own biography and then through her two Cold War productions, the 1952 play

Gold Through the Trees and her columns in

Freedom, which were the basis for her 1956 novel

Like One of the Family, and, finally, through three post–Cold War productions, her 1966 play

Wedding Band and two novels,

A Short Walk (1979) and

Those Other People (1989).

CHILDRESS’S HOMEGROWN MARXISM

As her friends’ testimonies and her own writings attest, Childress was an idiosyncratic leftist, and that was surely encouraged by her unconventional grandmother. Born in Charleston, South Carolina, in 1916, Childress moved briefly to Baltimore after her mother and father separated when she was five, and then to New York (they lived on 118th Street between Lenox and Fifth avenues in Harlem), where she was raised by her maternal grandmother Eliza Campbell, a relationship she considered one of the most “fortunate” things in her life, according to Elizabeth Brown-Guillory (quoted in Maguire 1995, 249). Formally uneducated and the daughter of an enslaved woman, Childress’s grandmother introduced her to New York culture, from art galleries to Harlem churches; cultivated her imaginative life; and nurtured her desire to write, telling Alice, even as a young child, to imagine stories about the people and places they encountered and to write down her important thoughts so that they could be preserved (Maguire 1995, 49). She attended elementary school in Baltimore and junior and senior high school in New York City and credits many of her teachers for encouraging her writing. The New York City high school she attended, Wadleigh High School, was founded by Lydia F. Wadleigh, an early crusader for education for girls; as the first high school in New York for girls, it may have been another place that encouraged her independence. Her grandmother’s interest in her cultural education may have pushed Childress to do some amateur acting, and her FOIA file reveals that she was active in theater as far back as junior high school with the Urban League and with the Negro Theatre Youth League of the Federal Theatre Project (U.S. FBI, Alice Childress, 100-379156, March 20, 1953). If Childress was working or acting in the Negro Youth League, then she was almost certainly exposed to radical politics, an affiliation that suggests she was formed politically at an early age by her associations with the Left as well as by grandmotherly influence.

After both her mother and grandmother died in the mid-1930s, Childress was left on her own and forced to leave high school after two years. Because Childress was notoriously reticent about revealing her private life, we know very little about her between 1935 and 1941 (Maguire 1995, 31). However, we do know from several biographical sketches that she supported herself working at odd jobs as a machinist, domestic worker, saleswoman, and insurance agent (J. Smith 2004, 295). Childress (then Alice Herndon) married Alvin Childress, also an actor, most famous for his role in the 1950s

Amos ’n’ Andy television show, with whom she had one child, Jean, in 1935. She also continued acting in leftist community theater. One chapter in her novel

Like One of the Family indicates that she was quite familiar with the FTP and the project actors. In one conversation with her friend Marge, the character Mildred discusses the “Negro problem” films of the late 1940s and reminds Marge that the Federal Theatre years (1935–1939) were a kind of golden age for black actors: they played in productions including

Turpentine,

Noah,

Sweet Land, and

Macbeth. Mildred’s familiarity with the productions and actors of the 1930s and 1940s indicates that her author may have been a part of the project, but Mildred stops Marge from talking about the Federal Theatre because Mildred fears people will find out their correct ages, a relevant comment for Childress because, like Mildred, she was hiding her real age, claiming 1920 rather than her actual birth date of 1916 (Maguire 1995, 31; Jennings 1995, 1).

11 The Federal Theatre closed in 1939 under accusations of “un-American propaganda activities” most probably earned because of its prolabor stands, its progressive politics on social issues, and its interracial casts.

In 1941, two years after the close of the Federal Theatre, Childress joined the American Negro Theatre, founded in 1939 by the actor and blacklisted revolutionary trade unionist Frederick O’Neal and the writer Abram Hill, to identify and encourage blacks in theater.

12 In the vision of O’Neal and Hill, the ANT, following in the progressive path of the FTP, was organized as a cooperative where actors, playwrights, directors, and stage crew would work cooperatively and, in contrast to the professional theater, “[share] expenses and profits” and develop artists and plays for the black community. The ANT operated for the first five years of its existence in the basement of the 135th Street branch of the New York Public Library, which seated 125 people, eventually adding the Studio Theater to train young artists, two of whom—Sidney Poitier and Harry Belafonte—became internationally known.

Childress spent the next eleven years at the ANT, working usually four nights a week, as demanded by ANT policy. Because the ANT operated like an arts academy, Childress had the opportunity to perform all the roles in the theater, including playwright, director, manager, actor, stagehand, and even, at one point, union negotiator. Her life in the 1940s was almost entirely consumed by the theater. She learned how to erect sets, coach new actors, do makeup, design costumes, and direct shows, and, whenever she could get a role, she acted in off-Broadway theater (Jennings 1995, 3). Along with fellow actors who started at the ANT—Ruby Dee, Ossie Davis, Poitier, and Belafonte—she starred in several of ANT’s most popular productions, eventually landing a part in the all-black cast of

Anna Lucasta, ANT’s first big-time commercial success. Written by the Polish-American playwright Philip Yordan,

Lucasta was originally about a Polish family, but, with Yordan’s permission, the play was revised by Abram Hill for a black cast, and it was the all-black ANT production that caught the attention of producers, who took it to Broadway in 1944 for 957 performances, earning Childress a Tony nomination for her role as the prostitute Blanche (Branch 2010). Poitier, Childress, Dee, Davis, and other ANT members joined the traveling company of

Lucasta, which toured the Midwest and East Coast. The young, self-identified “left of center” Poitier suggests in his autobiography that it was on this long road tour that Childress became his political mentor: “She opened me up to positive new ways of looking at myself and others, and she encouraged me to explore the history of black people (as opposed to ‘colored’ people). She was instrumental in my meeting and getting to know the remarkable Paul Robeson, and for that alone I shall always be grateful” (2007, 121–122). By 1955, the traveling four—Poitier, Dee, Davis, and Childress—would all be blacklisted for their close associations with Robeson, the Committee for the Negro in the Arts, and the ANT. When

Lucasta was made into a Hollywood film in 1958, starring Eartha Kitt, Sammy Davis Jr., Rex Ingram, and Frederick O’Neal, the part of Blanche was given to the unknown Claire Leyba, and Childress was passed over for the role for which she had garnered a Tony nomination, most likely because of her left-wing associations.

In 1951, the same year that Childress became a regular columnist for

Freedom, her husband Alvin, now an instructor at the ANT, was offered the role of Amos Brown, the philosophical cab driver in the controversial

Amos ’n’ Andy television series. Both Alice and Alvin were making very little money, so a television role meant the possibility of hitting it big, but it also meant both a physical and, eventually, an ideological separation. Alvin was working on the West Coast in the glamour world of Hollywood, and Childress was working in New York with the ANT and with the people at

Freedom, all of whom were highly critical of

Amos ’n’ Andy for its demeaning portrayal of black culture. Childress has said very little about their divorce, saying only that the marriage “was just something that shouldn’t have been” (Branch 2010). She was, however, so adamantly opposed to Alvin’s decision to stay in the series that she announced publicly at a forum on black playwrights held at the University of Massachusetts–Amherst in the late 1980s that she had divorced him for taking the

Amos ’n’ Andy role. As we will see in the “Spycraft” chapter, Childress was as firm in her rejection of the CIA as she was about her husband playing in

Amos ’n’ Andy.

13GOLD THROUGH THE TREES

In 1952, Childress produced her most clearly identifiably leftist play, the radical musical

Gold Through the Trees, and staged it in a cultural context so radicalized that it immediately caught the attention of the FBI. Almost without exception the commentary on

Gold has ignored its radical implications, but, if literary historians missed the significance of the play, the FBI certainly did not. The FBI report was extensive, observing that on May 20, 1952,

Gold would be produced by the left-wing Committee for the Negro in the Arts to benefit the left-dominated Civil Rights Congress (the CRC bought out the house for one performance), that the play would be performed at the progressive-interracial Club Baron at 437 Lenox Avenue at 132nd Street, and that it was reviewed favorably by Lorraine Hansberry in the left-wing newspaper

Freedom and by Lloyd Brown in the Marxist journal

Masses & Mainstream. As the leftist affiliation of each of these institutions and individuals shows, by the early 1950s Childress was fully embedded in the Harlem Left community, which supported the play as it ran for two months until, according to Childress, the leads were hired away to do the European tour of

Porgy and Bess.

Childress’s experiment with radical musical theater came the closest to providing what Michael Denning says in The Cultural Front was missing in other Popular Front musicals: a marriage of dramatic narrative, left-wing politics, and African American music. Countering Denning, Smethurst insists that a worthy precursor to Gold certainly must be Langston Hughes’s Don’t You Want to Be Free, which combined dramatic historical narrative, leftist politics, and African American music, and Childress was certainly familiar with Hughes’s theatrical work. Experimenting formally, Childress composed the lyrics and orchestrated the music and dance for the show, incorporating Ashanti dance, a Bantu love song, West Indian shouts and songs, drumming, and African American blues and gospel singing to accompany the play’s historically based, politically left-wing dramatic sketches that trace the history of African peoples from ancient worlds to the 1950s. If its sweeping coverage of thousands of years of history compromised dramatic unity, there were nevertheless three scenes of real dramatic power in Gold.

Act 1 features the fugitive Harriet Tubman working with two other women in a Cape May, New Jersey, laundry in 1852 to earn money for her underground trips. One scene in Act 2 is set in a prison, where a young man is on trial for the rape of a white woman in Martinsville, Virginia, in 1949. Based on the actual trial of the Martinsville Seven, the scene is narrated through the voice of the man’s mother and ends with the singing of the plaintive and politically charged “Martinsville Blues,” written by Childress. A woman narrator introduces the last act with a powerful monologue on the brutalities of colonialism, which sets up the final scene: South Africa in the 1950s, as three young activists meet to plan their part in the South African Defiance Campaign.

Two of the sketches in Gold—the Harriet Tubman scene and the scene in South Africa—are stories of reluctant activists discovering in collective resistance the courage to be involved in an underground movement, and these mirror Childress’s own political life in the 1950s. The Tubman scene is particularly notable in that respect: it features two women, Celia and Lennie, working with Tubman in the laundry at a luxurious seaside Cape May resort helping her earn money for her trips to the South to rescue enslaved people. According to the historical record, Tubman followed a pattern of seasonal migration, earning money doing domestic work in the North during the spring and summer and then heading south in the fall and winter, “when the nights are long and dark,” to execute her raids on slavery. Celia has become despondent over the heavy laundry work and fearful of their mission: she says the idea of working for the underground “sound so good in the meetin’ where it was all warm and friendly,” but she has begun to realize the dangers of being involved with a wanted fugitive. In a powerfully affective speech to encourage Celia to remain committed, Harriet uses the body as a tropological site, telling Celia to imagine that the broken skin on her knuckles is warm socks and boots for an escaping man or woman and that the cuts made by the lye soap is a baby that will be born on free soil. Trying to explain to Celia the transcendent feelings of crossing into both physical and psychological freedom, Harriet tells her that when she crossed that line, “There was a glory over everything. The sun come like gold through the trees” (7). The civil disobedience of these three women may certainly have been a disguised reference to Childress’s own underground work, since by 1952, according to her friend and leading communist Herbert Aptheker, who had gone into hiding, Childress too had crossed the line into subversive and illegal activity. Aptheker told me in an interview that during the worst days of the McCarthy period Childress let him use her uptown apartment for meetings with underground communists. This could have meant a jail term for Childress. Since this is not mentioned in her files, I conclude that the FBI never discovered the full extent of Childress’s radical politics.

The Martinsville section opens with a monologue by the mother of one of seven young black men accused of raping a white woman in Martinsville, a case that became a major cause for the Left when the Left-led Civil Rights Congress began mass public protests for the repeal of the death sentences and linked the CRC’s fight for the lives of the seven men to the constitutional rights of the CPUSA. Unlike the Scottsboro case, there was no question that Ruby Floyd had been brutally raped, that all seven men had been present, and that at least four had apparently participated in the rape. Desperately trying to avoid another Scottsboro, Virginia authorities produced “procedurally fair trials,” but there was, nonetheless, the lingering smell of Scottsboro: All blacks were dismissed. There was an all-white and all-male jury in all seven trials. Confessions were obtained without benefit of counsel, and some of the men may have been intoxicated at the time of their confessions. The jury in one case took only half an hour to sentence the defendant to the electric chair. In the largest mass execution for a single crime in U.S. history, all seven men were executed on two days, February 3 and 5, 1951, despite the mass protest of the CRC.

14The mother in

Gold narrates her son’s life through memories that show she had already anticipated the inevitability of trauma in his life. When he toddled out into the road as an infant, or caught his finger in his wagon, his screams prefigured the harm she knew she would be unable to prevent. Once he is older, those fears are realized as the young boy inadvertently tries to pay at the white counter in the grocery store and has to be whipped into submission to segregation. At the end of her monologue, the mother cradles an imaginary baby in her arms, and a single spotlight is turned on the face of a man, now behind bars singing “The Martinsville Blues”: “Early one morning / The sun was hardly high / The jailer said, Come on black boy / You gonna lay down your life and die. / Lord, Lordy, Lay down your life and die.” A second verse is sung by the condemned man to his mother, and another is directed to “Miss Floyd,” the white woman whose rape is the cause of his death sentence. At the end of the “Martinsville Blues,” the singer counts slowly to seven, inserting dramatically after each count the names of the seven executed men, a chant much like the one in Langston Hughes’s

Scottsboro Limited, where the count is to eight for eight of the nine Scottsboro men sentenced to death. The Martinsville section was not only an elegy for the dead but a song of protest made possible because of the Left’s activism that first fought to preserve the lives of the Martinsville men and then provided the space to lament the injustice of their fate.

Gold’s final scene, set in apartheid-era South Africa, is introduced by the narrator in a monologue that calls attention to the way the body of the colonized becomes the raw material for the productions of empire, showing again the Harlem Left’s deep consciousness of colonialism’s ties to European and American interests:

And the ships that had sailed away with gold and ivory returned to Africa laden down with German muskets, British and Portuguese guns … French weapons … and American blasting powder…. These weapons were for the purpose of hunting elephant…. Oh … yes…. They did hunt elephant…. Seventy-five thousand a year … and every pound of ivory cost the life of one African…. And I heard the delicate strains of the Moonlight Sonata played on that same ivory.

At the end of the monologue, three young South African revolutionaries are shown meeting in a shanty in Johannesburg where they make plans to join the rebellion against the apartheid laws. John, his friend Burney, and Ola, the woman he loves, speak to one another of their personal experiences with apartheid history, citing the pass laws, the mine accidents, the compulsory labor policies, and the prison farms they have endured, but they also report on the encouraging news of a new alliance among African, Indian, and Coloured, all demanding repeal of the “special laws.” In a scene taken directly from the African issue of

Freedom, Burney recalls the time that African women lay on the ground, forming a human carpet in the road to prevent police trucks from taking their men to jail. John announces that the campaign of passive resistance will begin on April 6, the anniversary of the arrival of the first Dutch settlers, with mass demonstrations and protests against the pass laws. The three say goodbye to one another, fully expecting to be imprisoned or killed, but with the knowledge that “through the resistance the world will have to move” (act 2, 7).

15According to the historian Penny von Eschen, activists like W. E. B. Du Bois, Alphaeus Hunton, Robeson, and, we must add, Childress deepened their insistence on the place of Africa in the consciousness of the Harlem Left with their support of the Defiance Campaign, knowing full well that this was a dangerous match-up (1997, 116). In the midst of the production of

Gold, the Harlem Left experienced the full brunt of repression: The Council on African Affairs’s director Dr. Hunton received a one-year jail sentence for contempt for refusing to divulge the names of contributors, Robeson’s passport was withdrawn, Du Bois was arrested and indicted for trying to get signatures on a peace petition, and Childress was unable get her work published in the mainstream press (Plummer 1996, 191). Very shortly after the 1952 production of

Gold, members of the theater committee, under the pressures of McCarthyism, “‘panicked’ and padlocked the door of the Club Baron themselves” (Duberman 1988, 703n29). Nonetheless, they all retained their commitment to linking African and African American struggles and foregrounding leftist political causes that Childress makes explicit in

Gold. If the underground in Ellison’s

Invisible Man—a far more celebrated 1950s black literary production—was a site for self-induced psychological paralysis, Childress’s black undergrounds were scenes inspired by a militant black international diasporic consciousness that imagined strategies for action, not retreat. In her focus on the outlaw Harriet Tubman, the Martinsville protest, and South African revolutionaries, Childress was not only drawing from the well of Left symbols, she was continuing her quest to represent blacks outside of the narrow, limited images of blacks in the American imaginary of the 1950s (Schaub 1991, 104; Schrecker 1998, 375–376).

16CHILDRESS, FREEDOM, AND CLAUDIA JONES

In contrast to the autonomous self she constructs in her 1984 autobiographical sketch, all of Childress’s work is permeated with images of community. In the essay she wrote for

Freedomways in 1971 about her life as a writer on Paul Robeson’s newspaper

Freedom, she situated herself at the center of a culturally cohesive black left-wing community, with Robeson working in the offices at 53 West 125th Street, alongside the dynamic, young communist editor Louis Burnham. The building also housed the Council on African Affairs, with offices occupied by Alphaeus Hunton and W. E. B. Du Bois. As she narrates, Childress imagines herself as a kind of roving camera, watching “Paul taking visitors to the offices of Du Bois and Hunton,” hearing their “deep and earnest conversation about Africa” (1971, 272). She remembers actors and musicians and neighborhood “Harlemites” dropping in to talk to Robeson, Eslanda Robeson introducing young artists to Burnham, Du Bois sitting in his office making a plan to complete his dream of

The Encyclopedia Africana, and a twentysomething “Lorraine Hansberry typing a paper for Robeson.” Childress shared an office with Robeson, Hunton, Burnham, and Hansberry, where she wrote her monthly “Conversations from Life” columns for

Freedom, one of the most popular features in the paper (Childress 1971, 272–273).

In this idyllic memoir, Childress omits the very Cold War history she was a part of. Once Robeson was blacklisted, the paper was unable to raise the funds to carry on and published its final issue in 1955, but Childress stayed with

Freedom until the very end. She wrote more than thirty columns called “Conversations” that featured Mildred Johnson—an outspoken domestic worker, Harlemite, and spiritual cousin to Langston Hughes’s Jesse B. Simple. Speaking in the first person, often to her friend Marge, usually a silent listener, other times to her white employers, and sometimes directly to the reader, Mildred speaks on a range of subjects, from the importance of Negro History Month to South African independence struggles.

17 Mildred is more of a consciousness-raising device than Hughes’s Simple, but like Hughes, Childress gave Mildred strong ties to the black community, an ease with vernacular speech, and a militant racial perspective, all intended to create an identification between Mildred and her working-class black readers. In 1956, Childress revised and expanded her “Conversations” and turned them into the novel

Like One of the Family, and because critical attention has always focused on the novel, these antecedent texts—the

Freedom columns—have been ignored, excising in the process another connection between Childress and the Left. Failing to trace the Mildred stories back to these Popular Front columns, critics could not situate the author or her protagonist in the context of Cold War politics and were easily led into limiting Mildred Johnson to race woman or “sassy black domestic” (Harris 1986). It is important, however, to read the Mildred monologues as they first appeared, not isolated in the autonomous and static text of the novel but as texts produced in the midst of Cold War tensions, in a left-wing newspaper, dramatically transformed by their dialogic relationship to the other stories and writers in the paper.

In the January 1954 issue, for example, Childress joined Robeson and the other Freedom contributors to launch an attack on the antiblack subtext of the HUAC and McCarthy witch-hunts. Mildred calls McCarthyism a form of legalized terror in which everyone from the Army, to the post office, to ordinary housewives was being investigated, and she predicts, “we are all going to suffer much more until we wake up and defend the rights of Communists.” Throughout the column, Childress/Mildred puts the major ideas of the paper in the language of an ordinary person in the community, trying to get them to understand the McCarthy purge as an effort to suppress thought and dissent that will affect them: they will have to “raid the libraries and remove all books that the ruling body in the land deems unfit … suppress all movies that they think unfit … close off every avenue they think unfit and put away or do away with all people who have such ideas, close all churches and social groups that hold such ideas these ideas and purge every home in the land to root out such ideas.” In another “Conversation,” again deploying Mildred as her political spokesperson, Childress affirms her support for Robeson, who by 1954 was under attack. When cautioned by a white employer that her involvement with Robeson will only cause her trouble, Mildred relates a folk tale about Old Master and his slave/servant Jim, with the subtext that “trouble” for the enslaved is rooted in the racism of Old Master. Revising the meaning of “trouble,” Mildred ends the tale by saying, “Somebody has made trouble for me, but it ain’t Paul Robeson. And the more he speaks the less trouble I’ll have.”

There is another reason to read Childress’s Mildred stories in a Left context. It brings to light an important collaboration between Childress and Claudia Jones, the secretary of the Communist Party’s National Women’s Commission and, at age thirty-five, the highest-ranking black woman in the CPUSA. Not only was Jones a substantial presence in the black leftist Harlem community, but in 1949 she published, in the leftist journal

Political Affairs, an important essay about black working-class women, “An End to the Neglect of the Problems of the Negro Woman,” which I believe helped inspire Childress’s Mildred character (Davies 2008, 79). No one has documented the relationship between Childress and Jones, but they almost certainly knew each other. They traveled in the same leftist-progressive circles in Harlem and knew many of the same people.

18 According to the

Freedomways editor Esther Jackson, Jones lived with Lorraine Hansberry when she first came to New York, and Childress became active with the Harlem Committee to Repeal the Smith Act at the same time that Jones was being threatened with deportation under the Smith Act. Born in Trinidad and raised in Harlem, Jones was a part of the group called the Sugar Hill Set, a group of artists and intellectuals in Harlem that included Hansberry, the Robesons, Langston Hughes, and Childress (Dorfman 2001). After being deported under the Smith Act, Jones died in London in 1964 at age forty-nine and, in honor of her political work, was buried in Highgate Cemetery literally to the left of the grave of Karl Marx.

19 The focus on Robeson in Childress’s life and work has obscured this radical left feminist influence on the construction of the Mildred character.

Jones argued that black women, as the most oppressed group in America and the least organized, were the most deserving of attention from the Left and should be at the center of leftist theorizing and strategizing about labor issues. Instead, she wrote, progressive leftists were guilty of “gross neglect of the special problems of Negro women.” With facts gathered from the U.S. Department of Labor, Jones set out to catalogue the evidence. Black women, she wrote, represented the largest percentage of women heads of households, having a maternity rate triple that of white women, and they were paid less than white women or men and were excluded from virtually all fields of work except the most menial and underpaid, namely domestic service. As domestic workers, black women were not protected by social and labor legislation nor covered by minimum wage legislation. Working in private households, they could be forced to perform any work their employers designated, sometimes standing on corners in virtual slave-market style with employers driving by and bidding for the lowest price. Despite these real-life roles black women were playing as workers, mothers, heads of households, and protectors of their families, Jones showed that the media continued to portray them as “a traditional mammy who puts the care of children and families of others above her own.” The conditions in Negro communities that resulted from those disparities in income and employment were, Jones wrote, with a sure sense of irony, an “iron curtain.”

In “An End to the Neglect of the Problems of the Negro Woman,” Jones also took her critique to those private spaces where discrimination against black women by progressives went unremarked. She cited instances where white women progressives called adult black women “girls,” or complained that their maids were not “friendly” enough, or drew the line at social equality, or, on meeting Negro professionals, asked if they knew of “someone in the family” who could take a job as a domestic (60). While leftist critics often cite Mike Gold’s story of a black woman who “could dance like a dream” (quoted in Maxwell 1996, 91) as evidence of the Party’s integrationist stance, Jones tells the story of black progressive women at social affairs being rejected for not meeting “white ruling-class standards of ‘desirability’” like light skin, discovering that discrimination existed even on the dance floor, where neither white nor black men were filling up their dance cards (60).

Freedom began monthly publication in November 1950 and ran until August 1955, when it folded from lack of funds and under Cold War pressures.

20 Its editor was Louis Burnham, an open communist, and appearing regularly were columns by Paul Robeson, Eslanda Robeson, Du Bois, Victoria Garvin, Yvonne Gregory, Hansberry, and Childress. It sold for ten cents an issue, one dollar for a year’s subscription, and followed a consistent format, with the motto of the paper under the masthead pointing to the internationalist-socialist focus of the paper: “

Where one is enslaved, all are in chains.” Each issue had front-page news followed by information about union and civil rights activities. Paul Robeson’s column, “My Story,” started off each issue on page 1 and often linked the various stories to Robeson’s personal activities.

21 The third page usually focused on international news and emphasized solidarity with people of color around the world. There were regular contributions both by and about Robeson and Du Bois. While gender was not as consistently raised as race, class, peace, and international solidarity, there was an understanding that gender was a separate and important issue. Both Childress and Hansberry, who became an associate editor after one year, and other contributors, including Beulah Richardson (later Bea Richards), Charles White, Shirley Graham Du Bois, Thelma Dale, Lloyd Brown, and the labor leader Vicki Garvin and at least fifteen other women labor activists helped shape the paper’s black-leftist-feminist viewpoint.

22

Childress made an enlightened, politically conscious Mildred the center of her narrative, as if to show, as Jones had pointed out, the possibilities of leadership in the very women white and male progressives were excluding. In one extended narrative on the importance of hands, Mildred pays tribute to working people by focusing on the physical labor required to bring the objects of everyday use into existence—from the tablecloth that Mildred says began in “some cotton field tended in the burning sun,” to the nail polish her friend Marge is using. When Mildred encounters a woman who is angry at “them step-ladder speakers,” a reference to Communist Party’s tradition of street-corner speeches, she gives a sermon on the value of “discontent” that introduces her readers to the Left’s contributions to their social welfare: “Discontented brothers and sisters made little children go to school instead of working in the factory,” and “a gang of dissatisfied folk” brought us the eight-hour workday, women’s right to vote, the minimum wage, unemployment insurance, unions, Social Security, public schools,

and washing machines. In her excellent introduction to the 1986 reissue of

Like One of the Family, the literary historian Trudier Harris correctly identifies the signs of Mildred’s radicalism. Harris says that Mildred confronts racial injustice, eradicates symbols of inequality, fights for labor rights, advocates collective resistance, and “radically violates every sort of spatial boundary.” Harris concludes that Childress’s militancy can be traced to Nat Turner, Frederick Douglass, Sojourner Truth, and Harriet Tubman. Since Childress was alive in 1986 and not eager to be identified as a leftist, it may have been prudent to attribute her politics to nineteenth-century radicals, but that again elides Childress’s left-wing politics and misses Mildred’s twentieth-century Marxism. With the Mildred character articulating the issues in Jones’s essay, Childress and Jones and Mildred were the three most important voices on the Left theorizing and representing black women workers in the 1950s. Contrary to the critics who reduced Mildred to a “sassy black domestic” or ignored Childress’s radical leftist profile, Childress meant for Mildred (like Jones and herself) to be a voice that provided black women with a theory of labor rights, authorization for dissent, and a language to speak against injustice; in other words, a bona fide woman of the Left.

BEYOND THE BLACK POPULAR FRONT: A WEDDING BANNED

With the CNA and the

Freedom family disbanded, she and her friends under surveillance, blacklisted, jailed, Red-baited, and/or deported,

23 Childress began writing her 1966 play

Wedding Band: A Love/Hate Story in Black and White in a period of crisis.

24 When the journal

Freedomways was founded in 1960, as the successor to

Freedom, Childress, along with her compatriots on the Left—Louis Burnham, W. E. B. and Shirley Graham Du Bois, Charles White, John O. Killens, Lorraine Hansberry, Elizabeth Catlett, and Margaret Burroughs—joined the editorial staff, a clear signal that they were still willing to be identified with the Left. While the journal was dedicated to continuing the internationalist-socialist aims of

Freedom, it also reflected a spirit of black radicalism that allowed them to remain engaged with the Left and give priority to black struggle.

Freedomways’s founders were so intent on maintaining “both the reality and appearance of black control” that they refused to ask the leading white communist Herbert Aptheker to join the editorial board, “adamantly” insisting that the journal be organized and run entirely by African Americans.

25 For black leftists who were increasingly distrustful of white-dominated institutions, the highly inspirational influence of the Southern civil rights movement led by Martin Luther King Jr. and the emergence of the charismatic black nationalism of Malcolm X made the transition from “the Robeson era” to the civil rights era (Iton 2010, 61) almost a necessity.

Even as black activists made this transition, very few left any documentation of the internal conflict created by this move. Two of Childress’s generation who did produce such documentation are the actor and activist Ossie Davis and the excommunist activist and writer Hunter (Jack) O’Dell. In a private letter written in 1964 to his long-time friend, the black communist William (Pat) Patterson, published in 2007 by Davis’s wife actor Ruby Dee, Davis describes his anguished decision to move away from the Left, a departure triggered by a conflict over plans for the memorial for Du Bois, which Davis viewed as an example of the white Left trying to contain black authority. He begins by reminding Patterson of his sincere and long-term allegiance to the Left even when it was dangerous: “I was on the outside with Robeson and Du Bois.” Including his dear friend Pat in his list of heroes, he writes, “My heroes were Hunton, Davis, Patterson, Robeson and Du Bois.” Nonetheless, Davis says he now understands that it is necessary to break away from “Great White Papa,” and, in the full-dress rhetoric of black nationalism, he concludes that at this moment of the ascendancy of the “Negro struggle,” the Negro people are now the “vanguard” and must break away from the Left in order to discover “our own separate manhood and dignity” (205). In his 2000 essay “Origins of

Freedomways,” O’Dell describes a similar epiphany. By the mid1950s, O’Dell writes, “the mechanisms of the Cold War State were now in place”—loyalty oaths, the Attorney General’s Subversive List, investigative committees, Red Squads in police departments, blacklists—and then, he writes, “along came Montgomery—one of those moments of awesome significance” that demonstrated the power of community action and the “joyful spirit of unselfish commitment” mobilized around a proposition with universal appeal: “Better to walk in dignity than to ride in humiliation” (5). O’Dell realized that joining Reverend King in black movement politics was a kind of redemption from the increasing isolation of the Left. Reading Davis’s letter for the first time in 2009, O’Dell said that his own feelings about the decision to leave the Communist Party and join King’s movement echoed Davis’s. That was such a necessary and organic shift, he admitted, “I wasn’t even torn about it.”

26Childress made no such dramatic pronouncements about leaving the Left, and, though she was deeply affected by the fervor and challenge of the new civil rights movement, she did not become closely identified with either King or Malcolm X, as Davis and O’Dell did. In an unpublished nonfiction piece called “Harlem on My Mind,” Childress left no doubt that her continuing interest in radical political change would take a blacker and more internationalist direction. In her notes for this piece, she mapped out a black historical trajectory for her future work that included the formation of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, Fidel Castro’s postrevolutionary stay at Harlem’s Hotel Theresa, Rosa Parks’s defiance of segregation laws, and “the birth of a baby in the West Indies” named Frantz Fanon, who, she writes, was “destined to call for a black revolution that would be studiously read by Harlemites, Africans, West Indians, and South Americans.” As these unpublished notes indicate, Childress was intellectually engaged in the fierce political currents of the early 1960s, but her typically iconoclastic response to this new era of black political struggle was Wedding Band in which she imagines “the indigenous current of black militancy” in the figure of a Southern working-class black woman and situates that woman in an intimate relationship with a working-class white man (Singh 2005, 184).

Not unexpectedly, black nationalists openly reviled Wedding Band. Childress’s close friend, the writer and fellow leftist John O. Killens, writing twenty years later, came close to calling her a race traitor for portraying a black woman loving a white man:

Childress’s other writings seemed to have a total and timely relevance to the Black experience in the U.S. of A.;

Wedding Band was a deviation. Perhaps the critic’s own mood or bias was at fault. For one who was involved artistically, creatively, intellectually, and actively in the human rights struggle unfolding at the time, it is difficult, even in retrospect, to empathize or identify with the heroine’s struggle for her relationship with the white man, symbolically the enemy incarnate of Black hopes and aspirations. Nevertheless, again, at the heart of

Wedding Band was the element of Black struggle, albeit a struggle difficult to relate to. As usual, the art and craftsmanship were fine; the message, however, appeared out of sync with the times.

(1984, 131)

Source: Copyright © 1973 by Alice Childress. Used by special permission of Flora Roberts, Inc., and Samuel French, Inc.

Wedding Band so unnerved Killens that he conflated Childress (the writer involved in artistic struggle) and her main character Julia (the heroine struggling in an intimate interracial relationship), reflecting the anxiety among black nationalist men over interracial desire between a black woman and a white man (Childress 1973, 8).

27

I want to challenge the view that

Wedding Band was a “deviation” from Childress’s earlier commitments and that her message was out of sync with the times” and show that her earlier investments in radical black leftist politics also animate this play.

28 Childress clearly had the contemporary moment in mind as she constructed a play that turned 1950s integrationism on its head. In what the historian Penny von Eschen calls a new “rewriting of race and racism” and the cultural historian Nikhil Pal Singh calls the race project of the “U.S. race relations complex,” Cold War liberalism, in reaction to the leftist radicalism of the 1940s, reinterpreted race as a psychological disorder rather than a system of economic, political, and social structures and practices connected to the subjugation of minority peoples all over the world. In opposition to the Left’s analysis of racism as located in systems of domination—slavery, colonialism, and imperialism—racism could now be understood in the metaphor of a “disease,” or an aberration, or the personal “prejudice” of unenlightened individuals, which could be overcome by talented, motivated, educated blacks with a “fighting spirit” (Von Eschen 1997, 153–159). Postwar civil rights militancy, with its emphasis on the black worker, its focus on the relationship between racism at home and colonialism abroad, and its advocacy of black equality, was being conveniently and systematically replaced by the integrationism of the 1950s or what the communist Ben Davis called derisively “a new race discourse of individual success stories,” which were designed to undermine the militancy of the fight for jobs and freedom for the masses of blacks.

29 At the same time that racial integration was being hailed as a sign of Negro progress, integrated unions, with their strong record of antiracial work, were being decimated by anticommunist hit squads, and interracial relationships and support for Negro equality were being designated un-American by government investigative committees. With the black radical Left weakened by investigative committees, blacklists, subpoenas, arrests, and jail terms, racism became domesticated, diverted into Cold War narratives of racial progress and individual achievement.

Wedding Band’s focus on the collective and on community solidarity and black protest, its critique of white race privilege and American nationalism, and its skepticism about the possibilities of interracial alliances contested these State Department–authorized versions of integration and questioned the entire project of Cold War-styled integration.

30

Source: Art by Leslie Evans with permission from Leslie Evans.

Wedding Band opens on Julia Augustine’s first day in an unnamed small black South Carolina community, where the back porches and backyards of several houses are contiguous, bringing Julia together with three other black women and their families: Mattie and her lover October, who is away in the merchant marines, and their daughter Teeta; Lula and her adopted son Nelson, a soldier home on leave from the army; and Fanny, the owner of all these little backyard houses. Julia, a thirty-five-year-old, working-class seamstress, living in domestic service away from family and friends, has moved here, hoping that this community will accept—or at least tolerate—her relationship with a white man, Herman, a forty-year-old German American baker, whom she meets when she buys bread in his small bakery. In South Carolina they cannot be legally married, but Childress depicts their union as binding and stable and as ordinary as any ten-year-old marriage. At their private anniversary celebration, Herman gives Julia a wedding ring on a chain since she cannot wear it publicly. By focusing on a ten-year-old union, Childress dispensed with the major premises of the conventional interracial love story—passing, sexual seduction, titillating courtship, erotic sex, the exotic other, effectively deeroticizing the romance plot so as to focus on the politics of an interracial love affair. Childress seems to have anticipated the 1967 Supreme Court decision

Loving v. Virginia, which denounced laws banning interracial marriage not as private infringements but as public acts of violence that confined, excluded, and violated entire black communities (Childress 1967, 17–21).

31

At the end of the first act, Herman falls ill with influenza in Julia’s house, triggering the public implications of their interracial relationship: it is against the law in South Carolina for a white man to be found living—or dying—in a black woman’s house. Though the love story between Julia and Herman is foregrounded in the film version of the play, the stage version (and my reading) centers on Julia’s interactions with the people in this backyard community (Maguire 1995, 53–54). When Julia wants to call the doctor for Herman, Fanny warns her that the entire community will be punished if Herman is found in her house. Mattie and Lula will lose their jobs, Nelson will not be able to march in the parade, and the doctor will file legal papers. As Fanny warns her: “That’s police. That’s the work-house…. Walk into the jaws of the law—they’ll chew you up” (act 2, scene 1, 35).

Julia and Herman are thus forced to encounter the public racial history they were able to evade when Julia lived in isolated places, but, more importantly, in this new black community, Julia experiences the collective troubles and racial anger that make their former evasions impossible. Their relation-ship—now mediated by the material conditions of this impoverished black community and incidents of racial consciousness raising that form the central action of the play—is a set up that allows Childress to present her very carefully constructed intellectual arguments about race, class, gender, and collective responsibility.

Significantly, Julia’s first public act in this new community is to read Mattie’s letter from October. When Mattie, who cannot read, asks Julia to read the letter from October, Julia’s voice merges with October’s as he relates his encounters with racism in the military: “Sometimes people say hurtful things ’bout what I am, like color and race” (19). And it is Julia, not October, who thus hears and participates in the call-and-response with Mattie’s defiant vernacular: “Tell ’em you my brown-skin Carolina daddy that’s who the hell you are” (19). Later, Lula tells Julia about the time she got down on her knees and played the darky act in a segregated courtroom in order to keep her son Nelson off the chain gang. Unschooled in the ways of racial resistance, Julia responds in a voice of class-based gentility: “Oh, Miss Lula, a lady’s not supposed to crawl and cry,” and Lula, disdaining Julia’s airs, retorts: “I was savin’ his life” (57). In a clear repudiation of Killens’s accusation of race disloyalty, Childress (1967, 20) says she was also intent on representing a strong black male voice to counteract the usual paradigms of interracial stories: “The colonel’s sweetheart never seemed to know any men of her own race, and those presented were usually slack-kneed objects of pity. This caused me to see an admirable black man in the center of the drama, one who could supply a counterpoint story with its own importance, a man whose everyday existence is threatened with the possibility of a life and death struggle.” In the most charged encounter between Julia and this community, Nelson comes home smoldering in anger over being attacked by Southern whites for wearing his uniform in public, remembers Julia’s white lover, and narrates a bitter parallel tale of interracial sex: “They set us on fire ’bout their women. String us up, pour on kerosene and light a match. Wouldn’t I make a bright flame in my new uniform? … I’m thinkin’ ’bout black boys hangin’ from trees in Little Mountain, Elloree, Winnsboro” (41).

32Julia’s encounters with Mattie, Lula, and Nelson enable her to find a “racial” voice, which she uses to end the silences Herman has imposed on her.

33 It is also important to note that in these encounters between Julia and Herman, whiteness becomes a racial category, and the racial gaze is rerouted and focused on white race privilege. In the past, when Julia would begin a sentence with “When white-folks decide,” Herman would insist that “white” be deleted: “people, Julia, people” (28). When she reminds him that his mother once accused him of loving a “nigger,” he chastises her for remembering something that was said seven or eight years ago (25). Herman says he only wants “to leave the ignorance outside,” not to allow difference to threaten their love, even as his own racialized descriptions of Julia as “the brown girl” who is like “the warm, Carolina night-time” reaffirm his privileged status as the unmarked, universal subject (41). He insists that his folks, struggling German Americans, plain working-class people, looked down upon and exploited by elite whites, cannot be blamed for slavery or segregation. His father laid cobblestone walks until he could buy the bakery where Herman makes a meager living: “What’s my privilege … I’m white … did it give me favors and friends? … nobody did it for me … you know how hard I worked. We were poor…. No big name, no quality” (61). With only a tenuous hold on their white American identity, Herman’s mother Frieda and sister Annabelle, in an attempt to ward off wartime anti-German attacks by other Americans, have flags flying in the front yard, red, white, and blue flowers planted in the back, and a “WE ARE AMERICAN CITIZENS” sign in their front window (24). Although Herman is disgusted by their jingoism, he admits that his father joined a Klan-like organization, and he can still recite the racist speeches of John C. Calhoun he learned as a child (he does so while he is delirious with fever). Despite this history, Herman insists that their lives are essentially personal stories disconnected from race. Julia tells him she does not blame him for the past but for the silences he has imposed on her: “For the one thing we never talk about … white folks killin’ me and mine. You wouldn’t let me speak…. Whenever somebody was lynched … you’n me would eat a very silent supper. It hurt me not to talk … what you don’t say you swallow down” (62). When Herman defends his father as a hardworking man who “never hurt anybody,” Julia answers him in the present tense—“He hurts me”—undercutting Herman’s evasion of responsibility for a system that continues to privilege him and his family and to hurt Julia. In a newly freed voice, she rejects Herman’s description of her as “not like the rest” and claims a collective identity: “I’m just like all the rest of the colored women” (61).

Childress had already begun to critique postwar interracial stories in her

Freedom column “About Those Colored Movies,” where she exposed the interracial films

Pinky and

Lost Boundaries as duplicitous attempts to evade the larger issues of economic and political inequalities by foregrounding black anxiety and helplessness.

34 We might consider that the near-universal acclaim for Hansberry’s

Raisin in the Sun in 1959 was at least partly attributable to its optimistic portrayal of black progress toward integration and that

Wedding Band’s insistence on confronting the violence and repressed traumas of our “decidedly interracial history,” rather than romance or Negro progress, was not likely to go down as easily with a public being prepped for a decidedly rosier racial story (Singh 1999; 2005). Childress, however, set her interracial romance on the terrain of power, represented in large part by the oppositional interactions between Herman and Julia. Herman says it’s “the ignorance,” and he wants to leave the ignorance outside, as if there were an “outside” where white supremacy and black inequality did not exist. Julia insists on erasing that imaginary line, and “disturbing the peace” with her narratives of black struggle and a history grounded in racial discrimination and domination.

35 Herman’s ownership of the bakery, his insistence that white remain an unmarked category, and his geographic mobility literally and symbolically represent racial privilege; Julia’s enslaved ancestors, her sexualized brown skin, and her vulnerable homelessness are a sign of her status as the racialized other; thus,

Wedding Band becomes an analogue to, and a powerful critique of, the racist construction of U.S. racial subjects.

36 But my larger point here is that

Wedding Band’s portrayal of white racial violence and privilege, its focus on the working class and on communal responsibility, and its rejection of the Negro progress story are evidence of the oppositional leftist politics that informed Childress’s political thought and creative production.

Wedding Band marks Childress as a writer of both Popular Front and Cold War cultures. We can read the play as an allegory of Childress as an artist and leftist activist at the end of the 1950s. Her character Julia is a fancy seamstress and thus, like Childress, a working-class black woman artist. As the playwright’s notes indicate, Julia moves into the center house in this small black community, where “one room of each house is visible,” placing her under continual surveillance by all the neighbors (Childress 1966, production notes 5). Fanny, the landlady, does, in fact, spy on her when she is alone with Herman, and she informs on Julia to Herman’s family. Considering that during the McCarthy investigations, any kind of interracial connection was tantamount to declaring one a communist, there is another overlap between Childress and Julia. For being involved interracially, Julia is blacklisted by both whites and blacks, and, under South Carolina law, her interracial relationship, like Childress’s communist affiliations, was criminalized. Herman’s death at the end of the play, as well as his inability to relate to anyone in this black community, signals that their interracial alliance has proved neither safe nor enduring, and Julia hands her wedding band to Mattie, saying, “You and Teeta are my family now” (64). It is not too much of a stretch to see this scene as Childress questioning the interracial alliances of the Left and attempting to establish, as she did in her work after 1966, a deeper sense of connectedness with black community and black culture. Keep in mind, however, that at the end of the play, Julia remains both insider and outsider, and Childress refuses any claim that Julia can become “authentically” one with the “folk.” Even as Julia asserts a spiritual unity with the people in this Southern community, the wedding band on a chain, her ten years with Herman, her status as a skilled seamstress, and her ability to speak for the community preclude any easy identification with that community. Once again we see how much Childress’s work is influenced by her involvement with the Left. As she did with her Mildred character in the pages of

Freedom, she recast the militant-intellectual-worker as a woman; she represented the reconnection of that figure with the folk community as partial, difficult, and provisional; and, most effectively, she drew from the Left’s uncompromising critique of 1950s race liberalism as a powerful source of literary and cultural self-determination.

37

CHILDRESS’S LEFT LEGACIES: A SHORT WALK AND THOSE OTHER PEOPLE

Even in her final two novels published in the 1970s and 1980s, a leftist sensibility is evident in Childress’s representation of black subjectivity. Her 1979 novel

A Short Walk continues the oppositional politics and aesthetics of her earlier work.

38 Whatever her ambivalence about the Left’s interracial focus, her final literary productions suggest that that she believed that interracial struggle, so central to leftist politics, was crucial to political empowerment. An episodic and impressionistic bildungsroman,

A Short Walk traces the life of Cora James from 1900 to the end of World War II. That time frame allowed Childress to insert a positive representation of the Communist party, replaying the Left of the Depression 1930s, when the communists organized interracial Unemployment Councils, challenged segregation, and fought evictions, making historic gains for the Party in black communities. In contrast to the eviction scene that appears in several black texts—most famously Ellison’s

Invisible Man, which depicts communists as strange and duplicitous outsiders—Childress uses the eviction scene in

A Short Walk to normalize communists. Cora describes the encounters between the evicted blacks and the communist activists as part of an interactive and personal relationship:

Folks from the Communist Party come around after the marshall leaves, knock the lock off the apartment door and move the people back into their place. Makes the landlord mad cause he has to pay the marshall each time for putting things out. The neighbors chip in and buy containers of beer for the Communist Party and also bring odds and ends of food to make up a “welcome home” party for the evicted.

(281)

Using the affective and intimate terms of an insider familiar with communist culture and practice, Cora describes the Communist Party as an organization with naturally occurring disagreements and misunderstandings as well as with affective bonds between blacks and whites.

After the eviction, Cora’s friend Estelle invites her to a communist cell meeting, which she attends at first with trepidation, only to discover that a so-called cell is merely someone’s flat where there are readings and discussions of politics and an exploration of real antagonisms between blacks and whites. At one meeting when a Negro comrade is angered because a white comrade acts high-handed and uses many unnecessarily big words, Party leaders initiate a discussion about the problems of white chauvinism, a phrase used by the Communist Party. When they show Cora two booklets on

The Woman Question and

The Negro Question, Cora challenges the way gender and race are subordinated to issues of labor: “I asked why the word

question was in it at all,” because, she says, when they deal with the issue of unemployment, they don’t refer to it as “

The Unemployment Question” (290). Though Cora is frustrated by the Party’s hesitancies on these issues, she defends communists to a friend who charges that they are just trying to use black people: “‘What the hell you think the Republicans and the Democrats doin with us?’ She [Cora’s friend] fell out laughin. ‘Yeah,’ I said. ‘They can show Communists what usin is all about!’” (290). At a Christmas party given by Cora’s friend Marion, both black and white communists join in the celebration, bringing their guitars, singing work songs, and attempting “to put social meaning to the blues” (299).

In a departure from most mainstream African American literature prior to the twenty-first century, A Short Walk openly represents queer sexuality. Childress ends the novel with a homosexual cross-dressing performance by Cora’s friend Marion, who wins the first prize at the cross-dressing Hamilton Ball, an expressive and colorful spectacle where no one can tell the difference between women and men and where whites and blacks of all classes mingle in open defiance of official norms. As a novel that violates hegemonic prescriptions about sexuality, class, race—and the Communist Party—A Short Walk might arguably be considered Childress’s most oppositional and radical text (Washington 2007, Higashida 2009).

In her final literary production,

Those Other People, a young-adult novel about a young, white, gay male computer instructor that Childress published in 1989, she returned again to issues of interracialism and leftist politics, which for her always seemed to be paired. In this novel Childress extended and revised the lessons of the Harlem Left Front, which was relatively inattentive to issues of sexuality, by putting queer sexuality at its center. The novel is constructed in a