So dear friend, I must perhaps go to jail. Please at the next red-baiting session you hear … remember this “Communist.”

—LORRAINE HANSBERRY, “LETTER TO EDYTHE,” 1951

You scratch a black man in the Communist party and you’re going to find a black man.

—JULIAN MAYFIELD, INTERVIEW WITH MALAIKA LUMUMBA, 1972

WITH THE EXCEPTION of Chicagoan Gwendolyn Brooks, all the writers of

The Other Blacklist were gathered at the Henry Hudson Hotel in New York City in 1959 to participate in what was billed as “The First Conference of Negro Writers.” Held from Friday, February 28, to Sunday, March 1, 1959, the lavishly funded three-day conference was modeled after the Presence Africaine conferences of the Paris-based Society of African Culture and sponsored by an offshoot of SAC, the American Society of African Culture (AMSAC), whose stated goal was to facilitate “links between culture and politics in Africa and America” (“The American Society of African Culture and Its Purpose”). The following year, selected papers from that conference were published in a slim volume, using the conference theme as its title,

The American Negro Writer and His Roots, and edited by AMSAC President John A. Davis, a professor of government at the City College of New York.

1 As Davis stated in his preface, the broad purpose of the conference was “to assess [the progress of Negro writers] and their relationship to their roots,” with “roots” suggesting only a slight nod toward the “Africa” in AMSAC’s self-description, since all the participants were American.

2 Just as a questionnaire had shaped the 1950

Phylon symposium a decade earlier and steered its participants into a narrow self-reflection, the AMSAC “roots” theme was designed to circumscribe and limit the speakers, obscuring a contentious debate that emerged at the conference between the conservative integrationists (also known as anticommunist race liberals) and the leftist radicals. The resulting book, which omits, edits, and marginalizes the comments and speeches of some of the most radical speakers at the conference, both subdues those debates and becomes, I will argue, another example of the imaginative and ideological battles over representing race in the Cold War 1950s.

I began

The Other Blacklist to challenge the ways African American literary and cultural histories have downplayed, ignored, minimized, or omitted the influence of the Communist Party and the Left in African American cultural practice of the “high” Cold War 1950s. In doing so, I have tried to correct the tendency in African American studies to treat communism and the Left as pejorative or irrelevant or to confine the Left’s influence on black writing to the 1930s and 1940s. It is especially important to avoid the amnesia that McCarthyism, the FBI, and the CIA have promoted. At a time when being on the Left or in the Communist Party guaranteed literary extinction, the writers and visual artist of my study—and, in this chapter, the outspoken Left speakers at the AMSAC conference—continued to articulate a leftist aesthetic and politics. They challenged State Department–authored versions of integration. They furthered the resistant traditions of the Black Popular Front and the 1940s civil rights movement. They spoke up loudly, clearly, and often in support of a literature and politics of social protest and, in the process, supplied a political and aesthetic vocabulary for the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s and 1970s.

3Since few scholars have taken up the task of a revisionary history of this conference, the task I have set for myself is to piece together as much as possible of the original AMSAC conference, looking behind the scenes and between the margins at the original speeches, the photographs, and the political and cultural contexts of the conference, which, I argue, show how the published volume was reconstructed to align smoothly with AMSAC’s political agenda. When the entire conference is studied, including the missing speeches and comparing the published volume with the conference presentations, we can see that it was clearly a site of ideological contest. This comparative interpretive strategy allows us to reread the conference and the published volume (and ultimately 1950s black literary history) as a three-way dialectic between an embattled internationalist Left (represented by John O. Killens, Julian Mayfield, Sarah E. Wright, Lofton Mitchell, Frank London Brown, Alice Childress, and Lorraine Hansberry) determined to advance black cultural and political self-determination; a conservative flank (Saunders Redding and Arthur P. Davis), promoting narrow national definitions of integration and race; and U.S.-government sponsored spy operations (John Davis, the CIA, the FBI, and Harold Cruse, working undercover), authorized to monitor and contain black radicalism.

4The signs of that struggle—between conservatives, liberals, radicals, and government spies—are embedded in the AMSAC conference, but the task of interpreting these signs is challenging. Nearly the entire original cast of players in the AMSAC conference, with the exception of William Branch and Samuel Allen, died before I completed my study. Some of the conference speeches were rewritten for the

Roots volume, and, at least in one case, an entirely different paper was submitted to the published volume. With the exception of Hansberry, original drafts and revisions of conference presentations are, as far as I know, not available.

5 Documentation of the conference planning and organization is spotty and sparse. Some of the most prominent black writers, including James Baldwin, Robert Hayden, and Paule Marshall, whose first novel,

Brown Girl, Brownstones, was published later that year, did not attend the conference. Harold Cruse says that Ralph Ellison refused to attend because he wanted to avoid Killens, who had written a negative review of

Invisible Man.

Langston Hughes spoke on “Writers: Black and White” with a double-voiced irony and barely concealed bitterness that distanced him from his former militancy, perhaps the result of his earlier shakedown by McCarthy. He tried to caution writers that the publishing industry is a crass, commercial, white-controlled enterprise that sees blackness through the eyes of commerce and partly through its own racism, a perilous and unpredictable course for black writers to navigate. A black writer, Hughes insisted, must work harder and write better but still will not be able to count on the success white writers expect. Replicating the crazy contradictions of race, he ends with this final paradox: “Of course, to be highly successful in a white world—commercially successful—in writing or anything else, you really should be white. But until you get white—write.” There would be no appearance by the highly sought-after writer Richard Wright, who was invited to come from Paris to give the keynote but eventually declined, so Hansberry, just three months away from her spectacular Broadway success, agreed to fill in for him.

It is important to take into consideration the silences and self-censorship of the left-wing participants, who did not openly identify as Left or communist. Moreover, as Langston Hughes reminded the audience, there were no black literary journals of the 1950s where these debates could have been expanded and explored in greater depth; thus we are, to some extent, confined to and dependent on these limited articulations provided by the published volume of the AMSAC proceedings. But one of the great values of the volume is that it allows us to tease out and foreground the leftist ideas and positions presented at the conference, and since, as I argue throughout this book, it is those ideals and ideas that encouraged political and aesthetic freedom for black writers, we are lucky to have the AMSAC archives, however tarnished by editorial emendations and CIA snooping.

FRAMING THE 1959 CONFERENCE IN THE ROOTS VOLUME: EDITING OUT THE LEFT

The epigraphs by Mayfield and Hansberry that open this chapter suggest that 1959—the year of the AMSAC conference—represented a crossroads moment for black leftist writers. In contrast to 1959, Hansberry in 1951 was so far to the left that she was fully prepared for and expected to go to jail. But by 1953, with the Red Scare intensifying, Hansberry left her position at Robeson’s newspaper

Freedom and applied for jobs at various publications, including the

New York Times, cautiously referring to

Freedom in her application as “a small cultural monthly” and listing her position there as associate editor at a “New York Publishing company” (Hansberry n.d.). When Hansberry’s 1959 hit play

Raisin in the Sun opened on Broadway, even her FBI informant could find no evidence of communist thought and concluded in the report, “The play contains no comments of any nature about Communism as such but deals essentially with negro [

sic] aspirations” (U.S. FBI, Lorraine Hansberry, February 5, 1959). In the next few years before her death in 1964, Hansberry, like many black leftists, was drawn to the civil rights movement and in 1964 wrote the text for the civil rights pictorial volume

The Movement: Documentary of a Struggle for Equality. Mayfield became a communist in 1956, even as its top leaders were going underground, because he considered the Communist Party the most radical organization he could join. But he also felt strongly that black nationalism, which was at the core of his radicalism, existed in uneasy tension with his leftist affiliations. For Mayfield neither the U.S. Left nor the U.S. civil rights movement was revolutionary enough: the communists of the 1950s were a problem because, in contrast to the 1930s, they “had no real effect on the black community,” and civil rights organizations were because they had turned away from the militant strategies of the black freedom struggles of the 1940s (Mayfield 1970). Tensions between blacks and the Left were exacerbated in the late 1950s as the Left suffered major setbacks under the Red Scare and McCarthyism and as many black intellectuals and activists were increasingly drawn to the black freedom movement. Complicating these issues for the leftist radicals at the AMSAC conference is that AMSAC and the conference were funded by the CIA, and many of the participants suspected as much. The conference thus became a forum where these tensions were played out and where, contrary to conventional notions of a quiescent 1950s, the black Left squared off against the conservative integrationists, prefiguring—and helping produce—the black cultural militancy of the 1960s.

Despite assimilationist visions and CIA collusions, the conference organizing committee that President Davis assembled was strikingly left wing, a strategic choice that the cultural historian Lawrence Jackson maintains was a brilliant tactical move on the part of Davis to camouflage AMSAC’s covert politics (2007, 721). Davis chose the left-wing novelist and Harlem Writers Guild director John O. Killens to chair the organizing committee, and Killens stacked the committee with his friends, including Mayfield, the leftist historian John Henrik Clarke, the progressive playwrights William Branch and Loften Mitchell, and the leftist writer and activist Sarah E. Wright. The conference also included a number of left-wing writers as speakers or panelists, including the playwright Alice Childress, the Chicago novelist and union organizer Frank London Brown, the recent McCarthy target Langston Hughes, and the playwright and activist Lorraine Hansberry. Though they may have been in the minority, the conservatives were well represented by the Howard professor Arthur P. Davis and the writer-scholar Saunders Redding, who were prepared to scrap any vestiges of social protest, which for them was rife with overtones of Marxist social consciousness and racial militancy.

6 The leftist lineup became a major concern for at least one ex-communist, Harold Cruse, the author of the Left-bashing

The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual, who drafted several pages of neatly typed notes, apparently for Killens, entitled “AMSAC Writers Conference Notes” (n.d.), in an effort to displace what he called the “Marxist oriented sphere of cultural activities” of the conference. Though there is no evidence of Cruse having any final say over the program, he warned Davis that the “lineup reflects too heavily the point of view which is known to be favorable to those white leftwing” and that it would give the impression “that AMSAC also agrees officially with this point of view in literature and racial politics.” Cruse then proposed that Childress, Mayfield, Mitchell, and Branch should be shifted about, dropped, and replaced so that a panel on social protest and its discussion of the topic “more democratically reflects a broader cross-section of views” (Cruse n.d.).

In light of Cruse’s warnings to Killens, it is not surprising that, when John Davis created the

Roots volume, he edited out the lively and controversial panel on social protest, specifically the papers in support of social protest given by Alice Childress and Frank London Brown. The only evidence we have of that panel is in the paper given by Loften Mitchell, which refers specifically to “the panel on social protest” and the controversy it produced. Because the final

Roots volume does not correspond to the conference organization, I have not been able to determine the exact format of the conference, but the table of contents in the

Roots volume indicates that the speeches covered the following topics: “The Negro Writer and His Relationship to His Roots,” “Integration and Race Literature,” “Marketing the Products of American Negro Writers,” “Roadblocks and Opportunities for Negro Writers,” and “Social Responsibility and the Role of Protest.” In a further neutralizing of the Left, Davis opened the volume with a preface promoting one of the hallmarks of Cold War ideology—that racial troubles are disappearing: “It is a tribute to both the Negro writer and America that this problem [black writers writing for a non-Negro audience] is being resolved, although much remains to be achieved” (iii). Davis added that the goals of black writers were “being true to their roots, accomplished and universal in their art, socially useful, and appreciated by a significant public.” Of course, the leftist writers at the conference argued that black writers, if they followed Davis’s list, risked becoming socially acceptable and politically irrelevant or, as Mayfield put it in his talk, on their way “into the mainstream and oblivion.” Davis did not refer to that debate. In another example of the manipulations and omissions behind the scenes of the published volume, Lorraine Hansberry’s closing address, arguably the most radical speech of the conference, was excluded from the final

Roots volume and not published until 1971 in

The Black Scholar. Davis also omitted John Killens’s “Opening Remarks,” which Killens’s biographer Keith Gilyard (2010, 141) says “echoed [the radical leftists] W. E. B. Du Bois, Paul Robeson, and Alphaeus Hunton,” with Killens proclaiming that “the American Negro’s battle for human rights mirrored the broader struggle of colored peoples throughout the world against colonialism.”

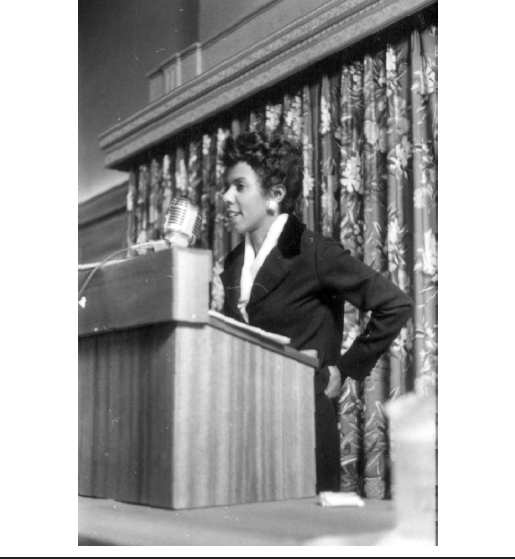

Source: Courtesy of the Moorland-Springarn Research Center, Howard University.

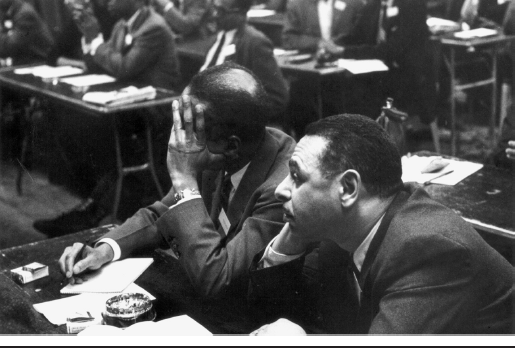

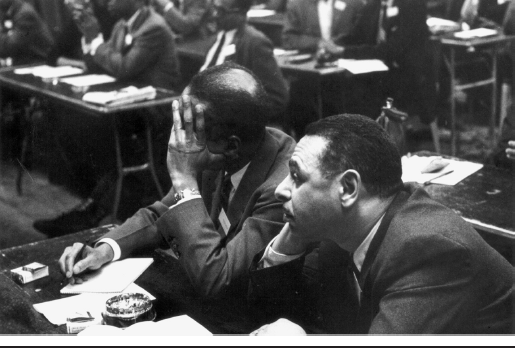

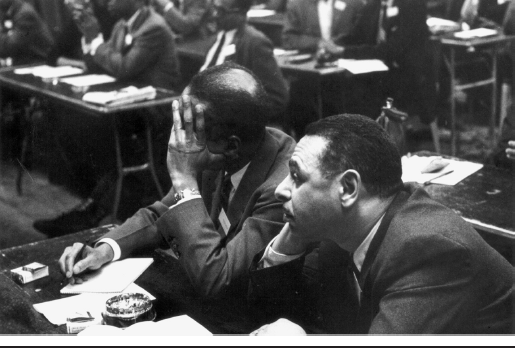

Surprisingly, Davis included a series of photographs, including some taken at the conference, that testify visually to the presence of the Left. On the opening pages opposite the title page, under the caption “The Many Postures of the American Negro Writer,” there are six candid snapshots of William Branch, Frank London Brown, Sarah E. Wright, Langston Hughes, and a group picture with several participants and John Davis at the conference. At the bottom right-hand side are pictures of the two open communists, the writers Lloyd Brown and Louis Burnham, neither of whom was invited to speak, listening intently to the proceedings (Burnham with one hand shielding his face from the camera). They were apparently sought out deliberately by the roving camera, since there are several different shots of them in the AMSAC files, though neither was featured on the program. The six members of the “Conference Planning Committee” are shown in headshots on the following page, looking dignified and serious. There are two pages of photographs at the end of the volume: Richard Gibson, a black expatriate writer, shown with the civil rights leader Arthur Spingarn; Alice Childress giving the paper that was omitted from the published volume; a group picture with Saunders Redding, Arna Bontemps, his son Paul, Irita Van Doren (the influential book editor of the

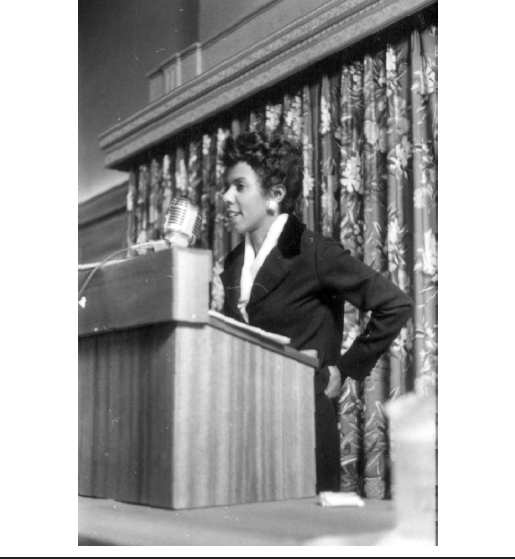

New York Herald Tribune), and Spingarn. Filling one-eighth of the page at the bottom is a picture of the missing “Panel on ‘Protest Writing,’” with the American flag conspicuously displayed in the center. Finally, on the last page, under the highly ambiguous and self-congratulatory caption “The Conference Closes with a Note of Success,” there are three photographs that point to the importance of Lorraine Hansberry’s presence: one shows her standing before a lighted podium, giving the closing address; one is a group shot with four men—Hughes, Redding, John Davis, and Bontemps; and, finally, the last is a photograph of the audience at the “closing session,” where Hansberry received a standing ovation for the speech that was omitted from the publication.

Source: Courtesy of the Moorland-Springarn Research Center, Howard University.

Source: Courtesy of the Moorland-Springarn Research Center, Howard University.

These photographs certainly document the existence of the AMSAC conference and its participants, but they also subtly manipulate our view of the conference. As Shawn Michelle Smith (2004, 7) observes, a photographic archive is never neutral:

Even as it purports to simply supply evidence, or to document historical occurrences, the [photographic] archive maps the cultural terrain it claims to describe. In other words, the archive constructs the knowledge it would seem only to register or make evident. Thus archives are ideological; they are conceived with political intent, to make specific claims on cultural meaning.

In this case, many of the photographs—particularly the formal portraits—are so staid that the book looks like a Chamber of Commerce brochure. In all of the images, the men are in suits and ties, dressed formally for what is clearly a downtown affair. Unless we know the subjects’ affiliations with the Left, the photographs obscure the conference’s radical tone. The AMSAC photographs, then, can be read as both a historical record of the event and as evidentiary traces that hint at what is hidden, manipulated, or distorted in the written text.

BLACK WRITERS AND THE CIA

With these political-literary debates in mind, I want to turn briefly to the relationship between the CIA and AMSAC.

7 By 1959, the Central Intelligence Agency’s infiltration of American cultural institutions had been operating for more than nine years. Through its major propaganda vehicle, a front called the Congress for Cultural Freedom established in 1950, their mission on one front was to counter the Soviet Union’s programs of cultural propaganda; a second aim was to conduct “cultural warfare” in order to discipline American art and artists for the work of Cold War culture. As the British journalist and CIA historian Frances Stonor Saunders (1999) reports, the Congress for Cultural Freedom (CCF) maintained offices in Paris and Berlin as well as in the United States, operating under a structure that mirrored that of the Communist Party—involving fronts, spy networks, clandestine money transfers, committed ideologues, and fellow travelers. Fronts like the Farfield Foundation were fairly easy to set up: “a rich person, pledged to secrecy, would allow his or her name to be put on letterhead, and that would be enough to produce a foundation” (1999, 127). The foundation would then funnel money to approved organizations, essentially employing a spying network, ostensibly to expose the dangers of totalitarianism, while exporting the culture and traditions of the free world (126). At some point during the 1950s, all of the major foundations—Ford, Rockefeller, and Carnegie—operated as “funding cover” for CIA funds (135), and Ford and Rockefeller, specifically, according to Saunders, “were conscious instruments of covert US foreign policy” (139). By the early 1960s, Stoner reports that Ford had funneled about seven million dollars to the Congress for Cultural Freedom (142).

8The extent of CIA operations in U.S. culture, the magnitude of its influence, and its expansive reach into literary, musical, and visual arts is, in Stoner’s estimation, astounding. Over seventeen years, the CIA pumped “tens of millions of dollars into the Congress for Cultural Freedom” (1999, 130). With fronts like the Farfield Foundation, the Norman Foundation, and Encounter magazine in place, the CIA proceeded to sponsor art and sculpture shows and literary debates and conferences in Europe and the United States. They published the anticommunist essay collection The God That Failed and sponsored an arts festival in Europe, which the French communist press labeled U.S. “ideological occupation.” In the visual arts, there were collaborations between the CIA and private institutions like the Museum of Modern Art. The CIA contributed to art exhibits in Europe and organized cultural festivals through the CIA-sponsored Congress for Cultural Freedom, establishing the CCF as “a major presence in European cultural life” (107). The presence of the CIA and the involvement of major figures in the art and literary worlds and government officials, all connected with and supported in some way by the CIA, make it impossible to overlook the fact that the CIA was a major force in U.S. culture throughout the 1950s and 1960s.

But, according to Hugh Wilford (2008), the CIA appeared to have had its greatest effectiveness in literature, where “the link between modernism and the CIA appears clearest,” especially “in the covert subsidies to little magazines such as Partisan Review” (116). In his extensive study of the CIA’s relationship to AMSAC and black literary work, Wilford shows that AMSAC was “the CIA’s principal front organization in the African American literary community,” intended, Wilford asserts, to ensure that black political thought would stay firmly within the boundaries of acceptable forms of anticommunism (200).

Wilford identifies two CIA concerns behind its involvement with AMSAC. The first was to ensure a flow of information about the emerging independence movements in colonial dominated countries, especially in Africa, and to steer these emerging independence movements away from communist influence. The second was to counter growing civil unrest in the U.S. South, sparked by white resistance to the civil rights movement. This unrest was being broadcast throughout the world and used by the Soviet Union to score propaganda victories against the United States as the site of racial violence against blacks. The U.S. State Department was looking for—and found—blacks willing to advertise a positive view of U.S. race relations to counter the images being shipped abroad of dogs attacking children in Birmingham and white adults heckling children trying to go to school, but the government’s promotion of African American intellectuals was most certainly contingent on their distance from the Left (Wilford 2008, 199; Plummer 1996).

On February 20, 1975, the

New York Times reported that the Manhattan-based Norman Foundation, a CIA front, had directed $50, 000 to the American Society of African Culture. Many members of AMSAC were suspicious that the CIA might be involved in it, but that did not deter them from participating in the organization. With offices in New York in the tony East Forties (where other CIA front offices were located) and a spacious Fifth Avenue apartment “for use as guest quarters” (Wilford 2008, 206), AMSAC had the CIA’s signature written all over it. As “money flowed in” for AMSAC operations like annual conferences, festivals in Africa, book publications, and expenses-paid travels to Africa and Europe, it would not have been hard to figure out those connections.

9 William Branch said that members wondered where all the money was coming from since no one was asked to pay dues or asked to sponsor any fundraising events. Branch (2010) says that the rumors began almost immediately: “For a number of years there were those of us who had suspicions about the money supporting the organization. We were told it was coming from various foundations. Certainly it was not coming from the members because there were no dues.” In a letter in the AMSAC files at Howard University’s Moorland-Spingarn Collection, the Boston University sociologist Adelaide Cromwell Hill reported that she remembered the exact time and place that someone suggested CIA sponsorship of AMSAC, and she makes clear that CIA involvement was intentionally not documented (cited in Wilford 2008, 213). When Yvonne Walker, one of AMSAC’s staffers, was interviewed, she reported that she was surprised that she had to be checked by the FBI and required to swear an oath of secrecy. Although Davis denied the link to the CIA, Walker says, “Dr. Davis informed the CIA on everything that was going on,” and she was sure that “they [the CIA officers] helped to steer some of the plans” (quoted in Wilford 2008, 214). Although Davis, as well as the other officers on the Executive Board, knew about the CIA connections, he never acknowledged his connections with the CIA or its sponsorship of AMSAC, even after they were established by the

New York Times.

10The leftists at the conference were not under any illusions about AMSAC’s funding. During a break in the conference, Lloyd Brown chatted with his long-time friend Langston Hughes at the hotel bar, remarking, “With its ample supply of free drinks of the best brands, the sponsors seemed very well funded.” Hughes replied, “By somebody with a whole lot of dough.” Brown responded, “Yes, and he can print all the money he needs.” Hughes merely shrugged and asked Brown if he planned to go along to the upcoming conference in Africa, also sponsored by AMSAC. But Brown had not been asked to go, “for the same reason I had not been asked to be one of the speakers—my long association with Paul Robeson” (1996 interview with author). And, he might have added, his open membership in the Communist Party. The AMSAC sponsor, Brown noted, “appeared from nowhere and vanished the same way” (1996), but, of course, these issues surfaced again in the 1970s when AMSAC was named in the Senator Frank Church report as a CIA-funded organization.

What must be addressed is the effect of CIA influence during its unimpeded seventeen-year campaign to control U.S. culture and, more specifically, the black literary and cultural Left. Wilford (2008, 116) wonders “how writing might have developed in Cold War America without the ‘umbilical cord of gold’ that united spy and artist,” a reflection that has implications for the direction of African American writing in the 1950s and 1960s and specifically for the First Negro Writers Conference. Any reading of the conference, then, must account for how the speakers, the conference program, and the published volume, directed and edited by Davis, were influenced by the presence and power of U.S. government spies and, even more to the point, how African American literary and cultural production of the 1960s and beyond continued to be shaped by these collaborations.

THE LEFT VERSUS THE “NEW NEGRO LIBERALS” AT THE AMSAC CONFERENCE

A close reading of the conference is telling.

11 Conference participants discussed a number of issues for black writers—from how to write for the mainstream to how to form autonomous institutions—but the dominant issue of the conference was the role of protest literature in this new era of “integration,” an issue clearly radioactive in the climate of the 1950s because protest writing had been associated with the Left and with a militant critique of American democracy and race.

12 Those who favored “integrationist poetics” (Houston Baker’s term for those who advocated assimilation rather than black nationalism) objected to protest in both formal and historical terms, defining it as synonymous with the naturalism of Richard Wright, as placing an excessive focus on racial problems, and sometimes simply as the inclusion of black characters as subjects. Their antiprotest position was, of course, buttressed years before by James Baldwin’s brilliantly argued attack on Wright and naturalism in the 1951 essay “Many Thousands Gone” as well as by the Cold War aesthetics that had demoted social realism and naturalism in favor of a modernist (nonracialized) aesthetic. Ironically, that position was also supported by Wright himself in 1957, in a lecture he delivered in Rome, “The Literature of the Negro in the United States,” in which Wright—the former communist—optimistically predicted, on the basis of the 1954 Supreme Court ruling against segregation in education, that African American writers would move into the mainstream and turn away from “strictly racial themes.”

13Whereas Lawrence Jackson (2010) says that the AMSAC conference was a clear signal that “the old guard was giving way and that the future generational conflict” would find its definition in the language of “assimilation versus black nationalism,” I read its integrationist stance as heavily favored in 1959, since the members of the “old guard” had the winds of anticommunism, the Cold War liberal consensus, U.S. global superiority, and CIA interventions at their backs. The old guard’s integrationist politics are perhaps most ably demonstrated in Arthur P. Davis’s

Roots essay. Davis—a professor at Howard, a Southerner, an eighteenth-century British literature specialist, and one of the authors of the pioneering 1941 anthology of black literature,

The Negro Caravan: Writings by American Negroes—was in his early fifties in 1959 and one of the old guard. He castigated the protest tradition as unnecessary and burdensome in this new “spiritual climate” of integration, presumably ushered in by the 1954

Brown v. Board of Education decision. Davis declared, prematurely as it turns out, that, with the

Brown decision, the enemy had capitulated, and so the black writer could no longer “[capitalize] on oppression” (35). Thus he urged writers to drop this “cherished tradition” of protest, abandon “Negro character and background,” “search for new themes,” “emphasize the progress toward equality,” “play down the remaining harshness in Negro American living,” and move “towards the mainstream of American literature” (39). Segregation, he predicted, will pass, like the “Inquisition or the Hitler era in Germany,” and then black writers will be able to “write intimately and objectively of our own people in universal human terms” (40). Without using the term “modernism,” Davis cited two modernists, Melvin B. Tolson and Gwendolyn Brooks, as examples of black writers working in “the current style,” which he said he admired because they did not, in his opinion, engage protest aesthetics but feature middle-class characters and stress life “within the group,” not “conflict with outside forces” (37). To authorize his stand against protest poetry, Davis cites Allen Tate’s Anglocentric backhanded praise of Tolson, who, Tate had written, represents “the first time … a Negro poet has assimilated completely the full poetic language of his time and, by implication, the language of the Anglo-American poetic tradition” (39). Davis’s misreading of Brooks, Tolson, and Tate is instructive. Both Brooks and Tolson were leftist modernists, and neither would have sanctioned Davis’s position on social protest nor considered Tate’s comment a compliment.

14A fellow traveler in Davis’s ideological camp was the scholar-critic Saunders Redding, a professor at the historically black Hampton Institute in Virginia; the author of several books of literary criticism, two autobiographies, and the 1950 novel of black alienation,

Stranger and Alone (a precursor to Ralph Ellison’s

Invisible Man); and one of the founders of a tradition of African American literary criticism. Additionally, and surely of great import to Redding, he was a member of the editorial board of the Phi Beta Kappa journal

American Scholar. As Redding contributed regular columns on black literature for the Baltimore newspaper

Afro-American, he became, according to his biographer Lawrence Jackson (2007), “the most widely read black literary critic in the US.”

In the speech Redding submitted for the Roots volume, he presented black literary history as a steady evolution from old traditions set by leaders like Booker T. Washington, through the “artiness” of the Harlem Renaissance and the political “alienation” of communism, to a final resting place in universality, a concept, he said, that will enable the black writer to understand his relation to a common human identity (8). With this view of racial history as inevitable forward progress, Redding minimized racism as “the actions of a few men,” producing “insupportable calamities for millions of humble folk” (2), and he predicted that when black writers throw off their fixation on race, they would be able to ascend to the towers of “universality,” where, presumably, all white writers resided, swaddled in that all-embracing but elusive humanity. In his recent work on black intellectuals of the 1940s and 1950s, Jackson argues for understanding Redding as a far more complex thinker than his AMSAC essay reveals, a sophisticated critic who, Jackson says, embraced a range of positions: “a modernist impatient with older patterns of race relations,” a bourgeois with a desire for mainstream approval, and a race man who valued black racial traditions (2010, 718).

However, that sophistication and subtlety was not on display in his comments at the AMSAC conference. In that limited forum, Redding was lofty and erudite, showing off his impressive knowledge of literary history and hinting at but failing to elaborate his position that black American writers were part of a “complex and multifarious” American culture and were, therefore, only

American writers. In what appears to be the speech he originally gave at the conference, published in 1964 as his “Keynote Address,” Redding much more explicitly states his controversial position that there is no separate African American cultural tradition and that American literature is the “bough” and American Negro literature merely the “branch.” In a point that would have been even more problematic for the AMSAC audience, Redding maintained that much of American Negro literature was supported by “pathogenic” forces that created in the American Negro writer “illnesses,” “self-hatred,” “a lavish imitation,” and “preoccupation with man’s doom rather than with man’s destiny” (283). Small wonder, then, that Redding retracted this essay and submitted the tamer version to the

Roots volume.

15The leftists at the conference, who appear to have outnumbered the opposition, objected to both the spirit and the letter of the speeches given by Davis and Redding. Despite their numbers, however, we must remember that the Left carried the burden of Cold War repressions, and their presentations are, not surprisingly, full of coded terms and silences. To make sense of those, we need to keep in mind the precarious position of the black Left in 1959. By that year the institutions that had supported black left-wing cultural production had been decimated through all sorts of Red Scare tactics, chief among them being named to the Attorney General’s List of Subversive Organizations (AGLOSO), a totally arbitrary list that allowed the attorney general to declare an organization suspect without any legal proceedings. One of the most effective and innovative leftist cultural organizations of the 1950s, the Committee for the Negro in the Arts, was dead in three months after being designated “subversive” by the AGLOSO (Goldstein 2008, 67). Robeson’s pioneering leftist newspaper,

Freedom, which gave Lorraine Hansberry her start in journalism, featured Alice Childress’s popular “Conversations from Life” columns, and generally covered and reviewed cultural work on the Left, was disbanded in 1955 under Cold War pressures. The theater committee of the Club Baron, where Hughes, Childress, and Branch had produced plays, was closed in the 1950s because of the threat of a McCarthy investigation. Blacklisted writers including Childress, Sarah Wright, and Mayfield were unable to get their work published for a time in the 1950s. Hughes was called before a Senate investigation committee and forced to disavow his leftist writing. Just a year before the conference, the FBI tried to get Sarah Wright fired from her job as a bookkeeper in a printing firm, advising her employer that Wright was known as “an admirer of Paul Robeson,” her husband, Joe Kaye, said in an interview. (Her boss refused to fire her, even though he was anticommunist.) We might also consider another reason for the Left’s circumspection: both AMSAC and its lavishly funded conference were sponsored by CIA funds funneled through a phony setup called the Norman Foundation. Given CIA surveillance, along with blacklisting, congressional investigations, arrests, and deportations carried out during the 1950s, it is not surprising that these writers couched their leftist positions in carefully guarded terms.

16If there was anything writers on the Left understood well, it was that these debates over protest literature and over representations of black subjectivity were State Department–authorized strategies to determine the kind of black literary production that would be sanctioned and promoted in the era of Cold War containment. The left-wing speakers rejected the conservatism of Redding and Davis because that conservatism prescribed a racial, political, and aesthetic litmus test for black writers. In view of the 1960s Black Arts Movement, however, the Left seems to have won the day. But while the leftist writers argued hotly for the continuing importance of protest literature, they failed to examine the implications of the term social protest, presenting it as though its meaning were stable, unitary, and self-evident. Along with external pressures felt by the Left, the fundamental problem with the Left’s support of a protest tradition was that they did not or could not define it in formal terms. So a term like “social protest” floated around the conference, acquiring different meanings each time it was used. The conservatives, on the other hand, were armed with concrete and detailed reasons for rejecting and discrediting protest writing. The leftist speakers seem particularly stumbling in their efforts to defend social protest and social realism, perhaps because of the political implications of social protest and the climate of the Cold War. But perhaps the speakers on the Left were simply reluctant to formulate a formal orthodoxy. For the leftist writers at the AMSAC conference, social protest was a flexible term, reflecting the kind of pugnacious stance they assumed in their defense of black writers’ freedom to explore black subjectivity in all its dimensions. In actual fact, they did not impose any formal requirements on writers and did not insist on some form of (Richard) Wrightian naturalism. Their own work ran the gamut from modernism to social realism.

The opportunity to debate the importance of protest literature at the AMSAC conference was particularly important, given that in the late 1950s there was no progressive or black cultural journal where these issues could have been debated more extensively and that white publications, including the putatively liberal journal

Partisan Review, ignored black writing and racial issues almost totally.

17 Together the three AMSAC participants—Mayfield, Wright, and Hansberry—constituted the progressive wing at the conference, each of them resisting the domination of the conservatives and trying to carve out an autonomous and politically progressive space for black writers. All three were close to or members of the Communist Party at one time. Mayfield was, at the time, a thirty-year-old novelist and radical activist; he had joined the Communist Party in the mid-1950s, when the Party was at its most endangered. Unfazed by its decline, Mayfield considered it “the most powerful, radical organization” that he could join, and he remained active with the Party and the Harlem Left throughout the 1950s.

18 Sarah Wright said later that the only reason she did not join the Party is that no one asked her. Her husband, Joe Kaye, identified himself in an interview as an active communist and described Wright as deeply involved in events sponsored by the Communist Party as well as in organizations that openly supported Party causes. Hansberry joined the Party as a student at the University of Wisconsin (Anderson 2008, 264).

Mayfield took on the conservatives, arguing in his paper, “Into the Mainstream and Oblivion,” that integration into the mainstream constituted “oblivion” for the black writer. Mayfield directly addressed the panel on social protest, rejecting the claim that social protest “had outlived its usefulness” because the Negro artist was on the verge of acceptance into the American “mainstream,” a word, Mayfield noted with sarcasm, heard repeatedly at the conference (30). Mayfield began by examining the political use of the word “integration” as a ploy for “completely identifying the Negro with the American image” (30). In a direct challenge to Davis’s integrationist stance, Mayfield says that for the black writer “to align himself totally to the objectives of the dominant sections of the American nation” would be to limit himself to “the narrow national orbit,” accepting uncritically all that the American nation-state stands for. Urging black writers to remain critics of the nation, sensitive to “philosophical and artistic influences that originate beyond our national cultural boundaries,” Mayfield was the only speaker at the conference to place black writers in an international context and to identify the transnational Cold War politics behind the increasing emphasis on integration:

Now, because of a combination of international and domestic pressures, a social climate is being created wherein, at least in theory, he [the Negro] may win the trappings of freedom that other citizens already take for granted. One may suggest that during this period of transition the Negro would do well to consider if the best use of these trappings will be to align himself totally to the objectives of the dominant sections of the American nation.

(31)

Though Mayfield’s talk drifts off at the end into a pessimistic and inept conclusion about the black writer remaining in “the position of the unwanted child,” he came the closest of any of the presenters to exposing the Cold War politics behind AMSAC and the coded meanings behind the conservatives’ rejection of social protest.

In her presentation, the thirty-year-old activist Sarah E. Wright, whose 1955 experimental poetry volume

Give Me a Child and her critically acclaimed 1969 novel

This Child’s Gonna Live have been nearly erased from black literary history, echoed the radical critiques of Alice Childress, Mayfield, and Hansberry. The integrationists, she maintained, supported a “dominant [white] aesthetic [that] does not accommodate the judgment, values, or needs of the Negro people, let alone the Negro writer.” Wright’s focus on the “aesthetic” and her critique of the New Criticism are important. While Wright addressed a number of practical issues—like getting black books into public libraries and urging black artists to use political pressure to get schools and libraries to purchase and use books by black authors—she was the only speaker to deal with the politics of aesthetics and the only one besides Mayfield to connect these issues to Cold War politics. She argued that it was crucial to understand how the construction of “protest” writing was manipulated by the politics of the academy, and she specifically implicates the theories of the New Criticism in Cold War strategies. Black writers, she asserted, “should expose those standards of aesthetics which are often deliberately, but more often unwittingly, conceived to destroy artistic vitality. The new critics’ plea for self-contained writing that will cause readers to move only within the experience of the composition must be recognized by Negro writers as a force destructive of rational relations to life” (63).

Wright made explicit the assumptions of the New Criticism that art must be (or could be) divorced from the political or the social, that it could be, in other words, a “self-contained aesthetic object” distinguished by qualities of complexity and ambiguity that mock the simplistic and moralistic aims of protest writing. Arguing clearly as a leftist, Wright identified this idea of art as “destructive” and pointed to the need for an alternative aesthetic, naming the Left-influenced Harlem Writers’ Guild of New York City as “an inspiring example” of the type of forum necessary to aid black writers in “formulating a meaningful aesthetic.” But it is worth noting that the conservatives at the conference had the institutional-theoretical support of the New Criticism, which, as Smethurst (2012, 3) reminds us, “had by this time completely dominated literary studies in U.S. academia, giving them a coherent aesthetic underpinning that the intellectual-artistic Left did not have.” Wright’s critique had little forcefulness since it had no equivalent systematic theoretical support. Her valiant efforts to discredit the reigning aesthetic-theoretical Mafia was like carrying a thimble of water to a forest fire.

THE MISSING HANSBERRY KEYNOTE ADDRESS

In keeping with his well-deserved reputation for iconoclasm and personal vendetta, the historian Harold Cruse claimed in his 1967 book

The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual, typically without any documentation, that Lorraine Hansberry’s keynote presentation at the AMSAC conference was so “inappropriate” it had to be omitted from the published volume. Cruse may have been right that the radicalism of her speech, though it might seem subdued to a contemporary reader, was too far to the left for editor Davis. Robert Nemiroff, Hansberry’s ex-husband and estate manager, says that the speech was omitted because Hansberry did not edit it in time for publication, which seems an unlikely explanation for excluding the keynote address by the star of the black literary world. It seems more likely that Hansberry’s use of terms like “white supremacy,” her critique of 1950s civil rights strategies, and her direct references to the Cold War, lynching, the 1955 Bandung Conference, and “paid informers” so alarmed Davis and his CIA sponsors that he used the excuse of her tardiness to ban the speech.

The text of the speech—ultimately published more than a decade later in

The Black Scholar—makes clear that Hansberry was not simply targeting the conservatives in her remarks. Instead, she seems to have been aiming at the larger audience of anticommunist liberals, whom she addresses indirectly, referring to a conversation she had with “a young New York intellectual, an ex-Communist, a scholar and a serious student of philosophy and literature” who is cynical about any possibility for political change. I take Hansberry’s entire speech to be a refutation of the claims that art and ideology must be kept separate—the “end of ideology” position of disenchanted postwar liberal intellectuals.

19 She began the speech with the simple assertion that all art is “social,” by which she meant

ideological, and by attacking the mainstream media—including film, television, theater, and the novel—which, she says, were intent on masking their own ideologies. In a bulleted list, she named the “illusions” that the mainstream media perpetrate while claiming to be ideologically neutral:

Most people who work for a living (and they are few) are executives and/or work in some kind of office;

Women are idiots;

People are white;

Negroes do not exist;

The present social order is here forever, and this is the best of all possible worlds;

War is inevitable;

Radicals are infantile, adolescent, or senile; and

European culture is the culture of the world.

In other words, Hansberry’s list critiques the media for producing an ideology that promotes whiteness as normal, represents blacks as Other, discredits radicalism, and defines culture from an Eurocentric perspective.

Hansberry was not advocating a simplistic reverse ideology that would represent black life in a positive light. She challenged the Negro writer to reject the cultural values of “white supremacy” that devalue black speech and black expressive production, but she also insisted that the black writer should fearlessly present “all of the complexities and confusions and back-wardnesses of our people”—including the “ridiculous money values that spill over from the dominant culture,” “the romance of the black bourgeoisie,” and “color prejudice” among black people.

Hansberry’s leftist politics are most apparent in her prescient critique of 1950s civil rights strategy. While she passionately remembered “the epic magnitude” of fifty thousand Negroes in Montgomery, Alabama, and nine small children trying to go to school in Little Rock, Arkansas, she challenged what she considered the “obsessive over-reliance upon the courts, [and a] legalistic pursuit of the already guaranteed aspects of our Constitution,” which, she said, “preoccupies us at the expense of more potent political concepts.” Like Mayfield, Hansberry reminded her audience that the Left’s pre-Brown (the Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision of 1954) racial justice struggles, built out of a coalition of trade unionists, civil rights organizations, left-wing groups, and communists, were focused on economic inequities and labor rights, not on “a simple quest for integration” (Biondi 2003, 7) set into motion by the Brown decision. The socialist aims of these earlier civil rights movements were, in Hansberry’s words, “more potent political concepts” constituted to insure “vast economic transformations far greater than any our leaders have dared to envision” and “equal job opportunity, the most basic right of all men in all societies anywhere in the world.”

In

The Lost Promise of Civil Rights, one of the most trenchant critiques of the NAACP’s pursuit of desegregation in education, the legal historian Risa L. Goluboff (2007) essentially vindicates Hansberry’s (and Mayfield’s) criticism of the political limits and ideological constraints of the NAACP’s litigation strategy. As Goluboff shows, when the NAACP “channeled [their] legal energy” exclusively toward fighting the harmful effects of discrimination in public school education, they turned the energies of civil rights struggle away from its earlier focus on labor rights, insuring that “psychologically damaged schoolchildren and the state-sponsored segregated school [would become] the icons of Jim Crow” (2007, 4; see also Von Eschen 1997). But there were a few, like Hansberry, Mayfield, Childress, London Brown, and Wright, who were willing in 1959 to critique what had become by the end of the 1950s the Cold War orthodoxy on race, on civil rights, and on African American cultural work. Going still further, Hansberry seemed to be dropping hints of the collusion of artists with the CIA, another possible reason her speech was jettisoned: “And until such time [as these changes are realized], the artist who participates in programs of apology, of distortion, of camouflage in the depiction of the life and trials of our people, behaves as the paid agent of the enemies of Negro freedom” (138). Connecting black racial issues to an international context, Hansberry said that she would tell the people of Bombay, Peking, Budapest, Laos, Cairo, and Jakarta (referring to the Bandung Conference and the Hungarian uprising against the Soviet Union) that Negroes are not “free citizens of the United States of America,” that her people do not “enjoy equal opportunity in the most basic aspects of American life, housing, employment, franchise,” and that “there is still lynching in the United States of America.” Briefly referring to the Red Scare in her own life, Hansberry said that she was the victim of a physical assault motivated by both the “racial and political hysteria” of the Cold War, a war she called “the worst conflict of nerves in human history.”

As we can see from the numerous handwritten revisions she made on the original copy of this speech,

20 Hansberry was stitching together the mosaic of political concepts that constituted the black cultural and political Left in the 1950s, showing it as an articulate and incisive vision of the black freedom struggle. It is striking after reading this speech—for years only available in the 1971 issue of

Black Scholar—to turn to the final page of the

Roots volume and to the photograph of Hansberry standing before a well-lit lectern and speaking into a rather large microphone before a very large audience, which gave her a standing ovation. The photograph is a surprising reminder of the absence of her remarks from that published volume. If, as Gilyard (2010, 142) notes, Hansberry spoke more militantly in this speech than she allowed any of her characters in

Raisin in the Sun, it may have been that the Henry Hudson Hotel, even under CIA surveillance, was, ironically, a more receptive space for that militancy than the theaters of Broadway.

THE CONFERENCE’S AFTERMATH

AMSAC, as I have shown, had unquestionably derived major sustenance from the “umbilical cord of gold” provided by the CIA. In his 1971 memoirs, Julian Mayfield began to contemplate uneasily the willingness of the black Left to be less than vigilant about the largesse derived from their relationship to AMSAC. He was disappointed with the nationalists at the conference for so easily making a truce with the AMSAC establishment and wrote to the politically and culturally progressive Black World editor Hoyt Fuller in the early 1970s, confessing to Fuller in a soul-searching moment that there was only one of his colleagues on the Left who consistently questioned that relationship and refused to accept the perks being offered:

Lest someone else hasten to point it out, I should confess here that apparently both Hoyt Fuller and I, along with a lot of others, worked unwittingly for the C.I.A. when we were members of the American Society of African Culture, AMSAC. In those innocent years, there was only one writer I knew, Alice Childress, who demanded to know where the money was coming from, and consistently stayed away from those fine receptions/and boat rides for [Leopold] Senghor, [Jaja] Wachuu and the like.

21

In a letter to John Henrik Clarke, Mayfield again remarked that Childress’s singular example continues to disturb, pushing him to consider the price to be paid by those who willingly allowed themselves to be innocent dupes:

How it works, I don’t know, but I am reminded of those pretty days when we were being sponsored by AMSAC, and, to the best of my knowledge, only Alice C. [Childress] asked, “Where is all the money coming from.” When at a joint lecture at Boston in 1961, I reminded Sauders [

sic] Redding of our C.I.A. connection, he didn’t seem to know anything about it. Now that I have to do R. Wright [Richard Wright] more thoroughly, I realize that, like the poor, the F.B.I. and the C.I.A. are always with us. The problem is what happens when they send in the bill.

22

Even though these are private musings, Mayfield is one of the very few writers willing to admit his complicity with the CIA. Certainly, as we see in the Frank London Brown chapter, the desire for inclusion and normalcy made it more difficult for black artists to critique white supremacy, especially when it came in the “pretty” disguises of what Nikhil Pal Singh calls “the material and symbolic nets of funding and prestige” (2005, 151). Despite that, Mayfield was at least willing to contemplate the bill that would come due and what it would cost him. In the epilogue, I turn briefly to Mayfield’s creative work, specifically his 1961 novel The Grand Parade, to see if and how he was able to resolve these tensions. Mindful of what James Smethurst and Alan Wald call “the continuities” of radical politics and poetics that paved the way for the militant writing of the 1960s, I look at how he represented and expanded protest writing and continued to produce a “black literary Left.” While I am also interested in asking how his left-wing literary and cultural orientation may have enabled or inhibited formal experimentation, I am most interested in how black Left radicalism’s powerful critique of the conservative politics of the Cold War 1950s, gave artists like Mayfield the freedom to resist conservative notions of integration and race that energetically sought to limit expressions of black subjectivity.

Most people who work for a living (and they are few) are executives and/or work in some kind of office;

Most people who work for a living (and they are few) are executives and/or work in some kind of office; Women are idiots;

Women are idiots; People are white;

People are white; Negroes do not exist;

Negroes do not exist; The present social order is here forever, and this is the best of all possible worlds;

The present social order is here forever, and this is the best of all possible worlds; Radicals are infantile, adolescent, or senile; and

Radicals are infantile, adolescent, or senile; and European culture is the culture of the world.

European culture is the culture of the world.