Notes

1 British annexation of Burma took place in three stages consequential to the Anglo-Burmese wars of 1824–6, 1852 and 1885, the last conflict culminating in the termination of the Burmese monarchical system and the incorporation of the whole country into the British Indian Empire.

2 J. S. Furnivall, Colonial Policy and Practice, New York, 1956, provides the most comprehensive overall analysis of the adverse effects of colonial administration on traditional Burmese society, a problem to which he had drawn attention as early as 1916 in his article ‘On Researching’, Journal of the Burma Research Society, (JBRS) vol. vi, i, April 1916, p. 4. John F. Cady, A History of Modern Burma, New York, 1958, chs. 4–5, also discusses the economic and social effects of British administration in Burma. Albert D. Moscotti, British Policy and the Nationalist Movement in Burma, Honolulu, HI, 1974, makes effective use of official police reports and statistics to establish a connection between the increase in crime after 1917 and economic and social problems. E. Sarkisyanz, Buddhist Backgrounds of the Burmese Revolution, The Hague, 1965, and Donald Eugene Smith, Religion and Politics in Burma, Princeton, NJ, 1965, investigates the effects of colonization on Buddhism and the Sangha. For the colonial impact on traditional education, see Maung Kyaw Win, ‘Education in the Union of Burma before and after Independence’, MA thesis submitted to the American University, Washington, DC, 1959; U Kaung, ‘A Survey of the History of Education in Burma before the British Conquest and After’, JBRS, vol. xlvi, ii, Dec. 1963; Hkin Zaw Win, ‘U, Koloni Khit kala (1860–90) ga Myanma pinya-ye dwin Byitisha aso-ya hsaung wet chet mya apaw hsan sit thon thaggin’, JBRS, vol. lii, ii, Dec. 1969; Michael E. Mendelson, Sangha and State in Burma, Ithaca, NY, 1975, pp. 147–61. The effects of introducing the British Indian judicial system to Burma are examined in Okudaira Ryuji, ‘Changes in the Burmese Traditional Legal System during the Process of Colonization by the British in the 19th Century’, South-East Asian Studies, Kyoto University, vol. 23, no. 2, Sept. 1985.

3 Furnivall, Colonial Policy and Practice, p. 105.

4 See Cady, A History of Modern Burma, pp. 178–9, and Maung Maung, From Sangha to Laity: Nationalist Movements of Burma 1920–1940, New Delhi, 1980, ch. 1, for early religious associations.

5 Cady, A History of Modern Burma, pp. 179–80; Maung Maung, From Sangha to Laity, ch. 1; see also Hla Kun, Hpe Pu Shein tho-ma-hot Bama naing-ngan-ye-go kaing-hlok-hke-thaw-hto-thon u, Rangoon, 1976, pp. 76–8.

6 Maung Maung, Burma’s Constitution The Hague, 1961, pp. 10–12; Maung Maung, From Sangha to Laity, ch. 1; Cady, A History of Modern Burma, p. 180, and Sarkisyanz, Buddhist Backgrounds, pp. 128–9, draw attention to early government suspicions of the YMBA.

7 Maung Maung, Burma’s Constitution, pp. 11–12.

8 For U Ottama’s role in the Burmese nationalist movement, see Cady, A History of Modern Burma, pp. 231–4; Maung Maung, From Sangha to Laity, chs 2–3; Smith, Religion and Politics in Burma, pp. 92–9; Mendelson, Sangha and State in Burma, pp. 199–206; U Ba Yin, U Hsayadaw Ottama, Rangoon, 1955.

9 In 1912 U Ottama wrote a book on Japan extolling the virtues of its people, but his speeches and activities showed that his political thinking was very much influenced by developments in the Indian nationalist movement. See U Ottama, U Hsayadaw and Thakin Lwin, U Ottama let ywei zin, Rangoon (?), 1976.

10 Furnivall, Colonial Policy and Practice, p. 143; Cady, A History of Modern Burma, pp. 193, 215–16, 218–19; Mendelson, Sangha and State in Burma, pp. 201–3. Thinhka, Azani gaung-zaungyi Didok U Ba Cho, Rangoon, 1976, pp. 66–9, discusses the differences between the Indian Congress Party and the GCBA.

11 The issues which led to the splits within the GCBA are discussed in detail in Maung Maung, From Sangha to Laity, chs 3–5.

12 Maung Maung, Burma’s Constitution, p. 16; Maung Maung, From Sangha to Laity, pp. 21–3. Cady, A History of Modern Burma, pp. 213–19, presents the strike as largely a political manoeuvre. Theippan Maung Wa, ‘Unibhasiti bwaikot’, in Theippan Maung Wa i khitsan sa pe ahtwe-htwe, Rangoon, 1966, gives the views of a student who actually took part in the strike. See also Amyo-tha ne shwe yadu ahtein ahmat sa-zaung 1970, Rangoon, 1970.

13 Maung Maung, Burma’s Constitution, p. 16.

14 Cady, A History of Modern Burma, pp. 217–21; Maung Maung, From Sangha to Laity, pp. 22–3. The views of those young men who were involved in the strike and the National Schools movement can be seen in U Hpo Kya, ‘Amyotha ne’ and ‘Amyotha kyaung mya keitsa’, in U Hpo Kya hsaung-ba-baung gyok, Rangoon, 1975, and Theippan Maung Wa, ‘Amyotha kyaung nhin Myanma Sa pe’, in Theippan Maung Wa Sa Pe Yin kyei Hmu, Mandalay, 1976.

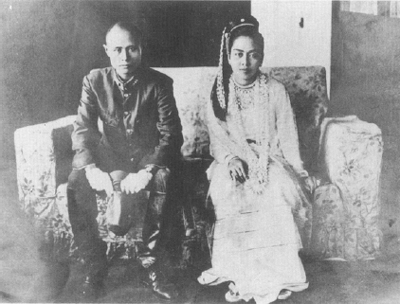

1. Wedding photograph of Aung San and Daw Khin Kyi, 1942.

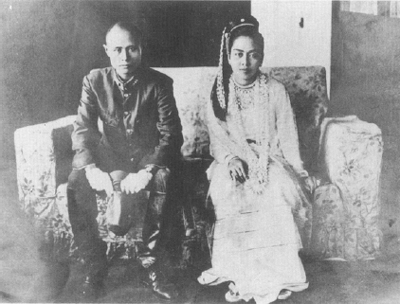

2. Aung San, his wife and children, Aung San Suu Kyi in the foreground.

3. Aung San Suu Kyi at the age of about six.

4. In her mother’s residence in New Delhi, 1965.

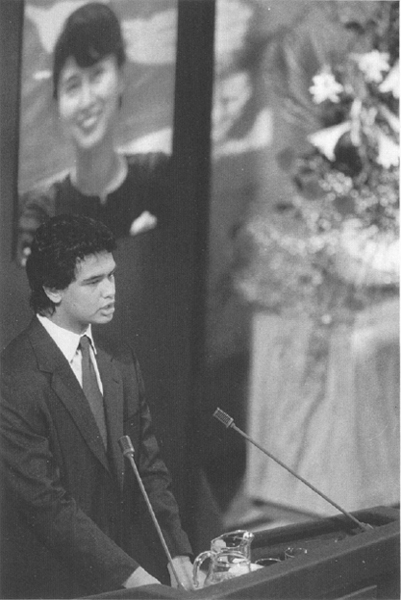

5. Alexander delivering the acceptance speech for the Nobel Peace Prize, Oslo, 10 December 1991. (Photo: Odd H. Anthonsen/Dagbladet, Oslo)

6. Suu and Michael, Burma, 1973.

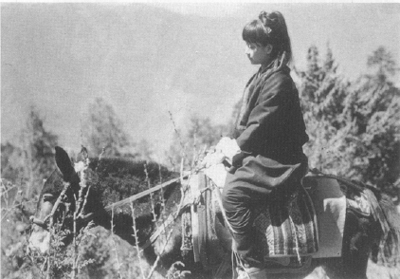

7. Mountain trip in Bhutan, 1971.

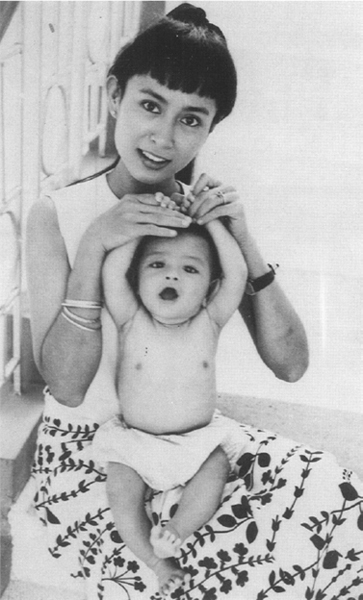

8. With her first-born son, Alexander, in Nepal, 1973.

9. At home in Oxford, 1983.

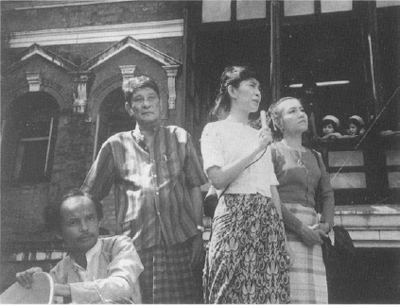

10. First public address at the Rangoon General Hospital, 24 August 1988, with the author U Thaw Ka.

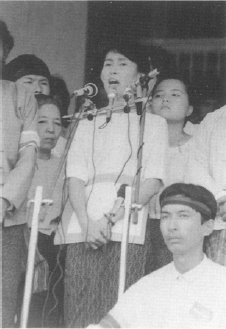

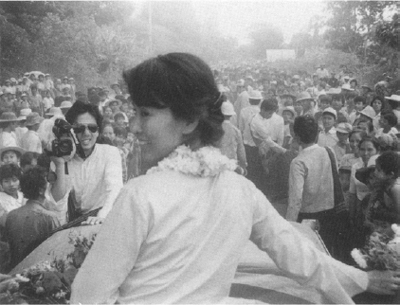

11. At the first of her mass rallies, Shwedagon Pagoda, 26 August 1988.

12. With former prime minister U Nu and party chairman Tin U, 1988. (Photo: Sandro Tucci, Black Star Inc.)

13. Campaigning up-country in 1989.

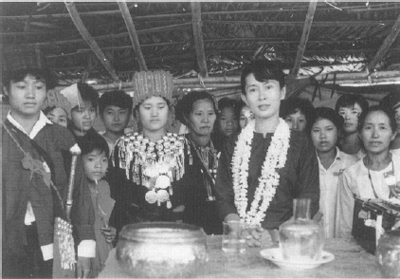

14. With supporters at a ceremony in Kachin State, northern Burma, April 1989.

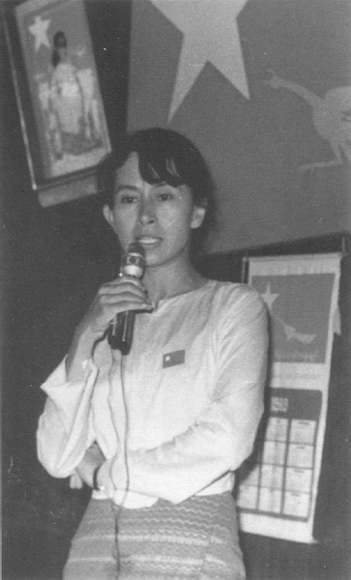

15. One of the thousand public addresses given in 1988–9.

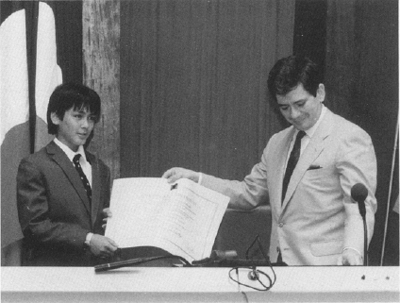

16. Kim accepting the 1990 Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought on his mother’s behalf, Strasbourg, 10 July 1991.

15 The ‘wunthanu spirit’ was an expression commonly used to denote patriotism but there were also wunthanu athins (associations), which worked closely with the GCBA. See Cady, A History of Modern Burma, ch. 7; Maung Maung, From Sangha to Laity, ch. 4.

16 Cady, A History of Modern Burma, Moscotti, British Policy and the Nationalist Movement in Burma, and Maung Maung, From Sangha to Laity, emphasize this aspect.

17 That sympathy for the rebels existed even among Burmese of the official class can be seen in Ba U, My Burma, New York, 1959. Mi Mi Khaing in her Burmese Family, Bloomington, In., 1963, ch. 8, is careful to point out that Hsaya San’s appeal was only to ‘a certain section of the population’ and to ‘some nationalists’; but at the same time, as a student in a missionary school, she seems to have vaguely identified the rebellion with patriotism. That there was considerable sympathy for Hsaya San among the students of Rangoon University is indicated by an article in The University College Annual, March 1931, vol. xxi, no. 3, p. 53, where it was said: ‘One thing that detaches romantic glamour from the Tharawaddy rebellion is the photograph of Saya San, who ousted the College-beaux from the fluttering hearts of the coy maidens of University College. He was dreamt of as the beau ideal and imagined as something in the way of the dashing dare-devil Don of the “Zorro” type.’

18 The introduction of leftist literature to Burma is studied in Frank Trager (ed.), Marxism in Southeast Asia, Stanford, Ca., 1959. A fair idea of the thinking of young leftist nationalists can also be gathered from studying the publications of the Nagani book club during the 1930s.

19 Among the leaders of the strike were Nu, Rashid, Thein Pe, Aung San, Hla Pe, Nyo Mya, Kyaw Nyein and others.

20 Zawgyi discusses the socio-economic forces behind the emergence of the Burmese novel in three articles in his Ya tha Sa pe ahpwin hnin nidan, Rangoon, 1976: ‘20 yazu nhit khit-u Myanma sa pe-i htuchet nhi yat’, ‘Myanma kalabo wut-htu hpyit po la pon leila chet’ and ‘Myanma kala-paw wut-htu’. See also Te’katho Win Mun, ‘Myanma wut-htu she thamaing’, in Wut-htu She Sa-dan-mya, Rangoon, 1981.

21 The catalogues of Burmese printed books in the British Library, London, and the India Office Library, London, give a good indication of the kinds of works popular with the Burmese public in the early decades of the twentieth century.

22 The first translated novel, however, was Robinson Crusoe, which came out in 1902. In his ‘20 Yazu nhit hkitu Myanma sa pe-i htu cha chet’, Zawgyi surmises that this book did not capture the imagination of the reading public because it lacked romantic interest.

23 There is as yet no complete biography of U Latt but there is a scattering of articles of which the most comprehensive is Taik So, ‘U Latt’, in Taik So and Min Yuwe, Myanma sa meit-hpwe, Rangoon, 1973.

24 U Latt, Zabebin, Rangoon, 1967, p. 24.

25 U Latt, Shwepyiso, Rangoon, 1977, pp. 47–8.

26 Ibid., pp. 123–7.

27 Furnivall, Colonial Policy and Practice, pp. 127–8, discusses the popularity of the legal profession among the Burmese.

28 See Sarkisyanz, Buddhist Backgrounds of the Burmese Revolution; Smith, Religion and Politics in Burma.

29 Taik So, ‘U Latt’.

30 There are a number of biographies of Hmaing, of which the best known are Thein Pe Myint, Thakin Kodaw Hmaing U Lun at-htokpatti, Rangoon, first published in 1937 (countered to some extent by Thireinda Pandita, Thakin Kodaw Hmaing athtokpatti hma-daw-pon, Rangoon, 1938); Tin Shwe, Thakin Kodaw Hmaing, Rangoon, 1975; Ludu Daw Ama, Hsayagyi Thakin Kodaw Hmaing athtokpatti, Mandalay, 1976.

31 This anecdote was first told in Thein Pe Myint, Thakin Kodaw Hmaing U Lun at-htok-patti, and repeated in some of the later biographies. Some have levelled the accusation that the monarchist sympathies of Hmaing were so strong that he regarded King George V and Queen Mary with a reverence unbecoming to a nationalist.

32 The links between Hmaing’s tikas and the Burmese nationalist movement are brought out in Zawgyi, U Lun: Man and Poet, Rangoon, 1957’ Than Tun, ‘Political Thought of Tikas by Hmine’, in Shiroku, Kagoshima University, no. 10, 1973; Tin Shwe, Thakin Kodaw Hmaing thu-khit thu bawa thu sa pe, Rangoon, 1968.

33 ‘Anya mingala zaung bwe Le-gyo-gyi’. For socio-economic conditions reflected in this work, see Min Thuwun, ‘Kyun bawa si-pwa-ye’, in Ludu U Hla, Zawgyi, U Ba Hpe and Min Thuwun, Thakin Kodaw Hmaing nidan, Rangoon 1971; see also Zawgyi, U Lun: Man and Poet, pp. 31–2. Daw Mya Mya Than’s article, ‘Myanma kabya thamaing (20 yazu)’, in Myanma kabya sa-dan mya, vol. 1, Rangoon, 1981, points out how Burmese poetry of the early twentieth century reflected social and political conditions in the country.

34 See Than Tun, ‘Political Thought of Tikas by Hmine’, on the difficulties of gleaning Hmaing’s social and political ideas from his tikas.

35 Hla Pe, ‘The Rise of Popular Literature in Burma’, JBRS, vol. li, ii, Dec. 1968, pp. 136–7.

36 The ideas behind the publication of the Khitsan works are explained by U Pe Maung Tin in his introduction to the first volume of Khitsan stories.

37 Min Latt, ‘Mainstreams in Burmese Literature: A Dawn That Went Astray’, New Orient: Journal for the Modern and Ancient Cultures of Asia and Africa, Prague, vol. iii, no. 6, 1962.

38 Some idea of the controversy over the Khitsan style can be gathered from Theippan Maung Wa, Theippan Maung Wa-i khitsan sa pe ahtwe-htwe.

39 That Theippan Maung Wa himself recognizes this can be gathered from his article on U Hpo Kya in Theippan Maung Wa Sa Pe Yin kyei Hmu, p. 45. See also Theippan Maung Wa-khitsan sa pe ahtwe-htwe.

40 A leading critic of Theippan Maung Wa was Thein Pe Myint: see his Tet khit tet lu tet hpongyi Thein Pe, Rangoon, 1975, pp. 110–13. Yet in his introduction to Thakin Kodaw Hmaing U Lun at-htokpatti, while he condemns writers who put themselves above the rest of humanity by purporting to be entirely objective, he makes no mention of Theippan Maung Wa, whose stories had already been published. However, he does protest against works that depict the poor as happy and contented, presaging the criticism that he would later level against Min Thuwun’s poems on the delights of village life.

41 The dilemma of writers like Theippan Maung Wa was not unusual under colonialism: for example, Bankimchandra Chattopadhyay, one of the leading figures of the Bengali renaissance, produced his nationalist writings only after retirement from government service. Theippan Maung Wa’s early death in 1941 prevents us from knowing how he might have developed as a writer in independent Burma.

42 Min Yuwe, ‘Pathama Myanma khitsan kabya’, pp. 143–52, and ‘Zawgyi-i bawa amyin’, pp. 153–68, in Taik So and Min Yuwe, Myanma sa meit-hpwe. However, it could be contested that the Khitsan poems did introduce new form and structure as the new arrangements of old styles resulted in considerable differences.

43 A collection of five poems by Zawgyi was published under the title ‘Zawgyi’s Patriotic Poems’ in the January 1936 issue of the Oway Magazine, vol. 5, no. 1.

44 U Hpo Kya, Ale-dan Myanma Yazawin, Rangoon, 1933; U Hpo Kya, Myanma gon-yi, Rangoon, 1938: U Ba Than, Kyaung thon Myanma yazawin, Rangoon, 1937; U Maung, Myanma yazawin thit, Rangoon, 1939.

45 The recourse to history for the bolstering of racial pride and nationalist ideals can also be seen in the novels of Bankimchandra Chattopadhyay and other writers of colonial India.

46 It has been speculated that Hmaing’s Dhammazedi wut-htu may have appeared earlier, around 1915. See Paragu, ‘Thamaing nauk hkan Myanma wut-htu she mya’, in Wut-htu She Sa-dan-mya.

47 Ibid., p. 81.

48 It is interesting to note that in his preface to the Myanma gon-yi yazawin hpat sa, U Hpo Kya states specifically that the book was not only about the Burmese but also about the Mons, Arakanese, Karens and Shans, while in the earlier published (1924) Myanma Gonyi he simply stated that it was about the people of Burma.

49 Adapted from Baroness Orczy’s Scarlet Pimpernel (1905).

50 Particular reference is made to the unhappy fate of one of the queen’s ladies-in-waiting, Khin Khin Kyi, with whom Thibaw unwisely fell in love. Daw Khin Khin Le later develops this story in her magnum opus, Sa-hso-daw wut-htu.

51 Thein Pe Myint explains his reasons for writing Tet hpongyi in his Tet khit tet lu tet-hpongyi Thein Pe.

52 Thein Pe Myint, Kyundaw-i achit-u, Rangoon, 1974, p. 226.

53 In his introduction to Thakin Kodaw Hmaing U Lun at-htokpatti, published in the same year as Tet-hpongyi, Thein Pe gives his views on the duties of writers.

54 See Daw Mya Mya Than, ‘Myanma kabya thamaing (20 yazu)’; She haung sa pe thuteithita-u, Pyi thu sa-hso Maung daung U Kyaw Hla thu khit-thu bawa thu sa, Rangoon, 1977. Thein Pe Myint wrote in the introduction to Thakin Kodaw Hmaing U Lun at-htokpatti that ‘during the period between the fall of Burma and the students’ boycott of 1920, there have not been known to have been any rebel writers other than U Kyaw Hla’.

55 Keith Thomas, Man and the Natural World: Changing Attitudes in England 1500–1800, Harmondsworth, 1984, p. 16.