10. Make a Soundtrack Stick with a Symbol

The government makes you eat your steak well-done in Canada.

They should tell you that at the border so you can make a game-time decision about whether you really want to enter the country. That was one of two rules I learned when I visited Vancouver, British Columbia.

The other was that it’s illegal to use your phone at the very first red light you come to after leaving the airport. It’s probably illegal at every red light, but that’s the one where they busted me in the least exciting sting operation ever.

My family and I had been in the country for about an hour. I hadn’t made a single “aboot” joke or any derogatory comments about moose. We were headed to Whistler for a few days of summer exploration, and everything was rolling along perfectly. At a red light, I pulled out my phone to check on some orphanages I support. Or I was going to tweet. It was one of the two. I can’t remember.

A police officer walked off the sidewalk and knocked on my window. I started to thank him for giving America Michael J. Fox and Alanis Morrissette, but that’s not what he wanted to talk about. “You can’t use your phone in the car,” he said. “I’m giving you a $300 ticket.” Oh Canada.

I deserved that ticket. At the time, I didn’t casually use my phone while driving—I was a power user. Responding to text messages is amateur. I was writing blog posts, capturing book ideas, and posting on social media with absolutely no regard for all the warnings on highway signs. Suffice it to say, I was not going to arrive alive and the text could not wait. If anything, I was surprised it took an international police force so long to finally capture me.

Out of Canadian kindness, the officer said, “It’s not your fault. The rental car company should have warned you about our new rule. When you return the car, tell them to pay your ticket.” That seemed like a terrible idea, but he had a gun, so I nodded along in agreement. He wrote me the only ticket I’ve ever received in my life and sent me north to the most beautiful mountains I never saw.

I missed that entire trip. I was there physically. I rode in the Peak 2 Peak Gondola. I hiked with my family. I ate a well-done steak that tasted like my shoe. But none of it could break through the noise of my overthinking. The second the officer told me to make the rental car agency pay the fine, I started rehearsing how that conversation was going to go.

That’s just one version of how overthinking told me things would go. Each one was less true, less helpful, and less kind than the rest. How could they not be? Remember, I don’t even like to ask autobody shops to do their job. Of course I’d overthink a conversation where I had to tell a rental car company to pay my traffic ticket.

“Look at that waterfall!” my wife would marvel as we drove up the Sea-to-Sky Highway, one of the most beautiful roadways in North America. “Stop overthinking the ticket. You can deal with it on Monday. You’re missing this whole weekend.”

“I am not,” I’d reply. “Do you think the person at Avis is going to get physical with me? Is this the French Canadian side of their country, because if it is, they might hit me with a white glove across the face. I think the French love that sort of thing.”

Three days later, I brought the car back to Avis and walked into the rental office. What happened next is going to surprise you. The actual conversation ended up being a lot easier than my overthinking told me it would be. A very polite Avis employee referred me to their customer service hotline and sent me on my way. Whole thing took about ninety seconds. I lost a three-day weekend over a ninety-second conversation. Has that ever happened to you? You got so lost in overthinking that everything around you became temporarily invisible? I made a whole coastal mountain range disappear, get on my level.

When I returned home to the States (that’s how you say “America” when you’ve traveled abroad to exotic locales like Canada), I was able to put the conversation behind me, but not my habit of texting and driving. That part of the ticket incident was still bothering me. I knew eventually I was going to get in a car crash. Though months later Officer Fred canceled my Canadian ticket, I knew I’d start getting tickets in Nashville too unless something changed. Worst of all, I was on the verge of teaching my oldest daughter how to drive. If I didn’t stop using my phone in the car, I was going to be a huge hypocrite every time I told her not to.

I had tried to quit before, but it was a hard habit to break. I’d put my phone in the trunk. I’d thrown it out of reach in the back seat. I’d turned it off while driving. Nothing really worked. I’d make it a few days but eventually find my phone back in one hand and the steering wheel in the other.

So, I did what any rational person would do in this situation. I went to the bank and got $200 in coins.

I Stumbled Upon the Power of a Symbol

I broke myself of the habit of texting and driving with a simple tool, but I’ve never written about it before because it’s a little weird. As I researched this book though, I realized I wasn’t all that special. I had just accidentally found one more way to repeat a new soundtrack.

That’s really all I was aiming for. In the same way that I said, “I can be a public speaker,” I was now saying, “I can drive without using my phone.” In chapter 2, you asked your broken soundtracks the question “Is it true?” so that you could retire them. Now you’re going to switch up the question a little bit to find a new soundtrack: “What do I want to be true?” I wanted to be the kind of guy who doesn’t drive with his phone. I wanted to be the kind of dad who can teach his daughter to drive without feeling like a hypocrite.

Just like when I started the public speaking adventure in 2008, I had very little evidence I could beat my phone habit. Every circumstance in my life said the opposite. But I didn’t just hope the soundtrack would work—I tied it to action. I knew I’d need a reminder or my new soundtrack would never stick. I wanted it to be simple, portable, and small. After a bit of thinking, I landed on coins.

Years ago, I bought a 1922 Peace Silver Dollar from a jewelry store on a whim. I kept it on my desk and would flip it whenever I felt stuck on an idea. I liked the way it felt in my hand. It was heavy. It was tangible in a world where most of my work isn’t. Tweets, emails, Zoom calls—none of those things have a real weight. I also like how it connected me to a different era. Seeing “1922” on it reminded me that there was more to life than just today’s challenges. Is that a lot to get from a coin? Yeah, I’m an overthinker. I really feel like that should be clear to you by now.

I decided that every time I drove without using my phone, I would give myself a dollar coin as a small symbol of my vehicular success. I didn’t have any dollar coins in the junk drawer at home, where coins congregate like an elephant graveyard, so I ordered two hundred from the bank. It took about a week for them to come in from wherever it is that banks keep old-timey money. Fort Knox, I assume? The O.K. Corral? No idea.

The teller at the bank didn’t think I was very odd when I picked up the money—at least not in that first visit. He just nodded, as if to say, “Here are the doubloons you requested, you suburban pirate,” and slid a small box across the counter. There in the parking lot, I grabbed a roll with twenty-five coins in it and put it in my cupholder. From that moment on, for the next two hundred trips, I thought about my phone and the coins. When I’d pull in the garage after going somewhere, if I hadn’t used my phone, I’d drop a coin into a big Mason jar that sits on my desk.

“It’s your own money,” my wife said one day as I unrolled another coin earned for a successful trip without my phone.

“What do you mean?” I asked, so proud of the fresh dollar coin I held in my hand.

“You’re not earning money. You took paper money to the bank. You turned it into metal money. Now you’re unrolling it coin by coin so that you can then someday reroll it and bring it back to the bank to turn into paper money again,” she said.

“It does sound a little crazy when you say it that way, but I don’t care, because it works.”

A fast way to find a new soundtrack is to ask yourself, “What do I want to be true?”

That’s a good summary soundtrack for my life: “It sounds crazy, but I don’t care, because it works.” It was certainly true in this situation. I spent three months going through every coin until all two hundred were in the jar. By the end of the experiment, I was no longer using my phone in the car. The coin made my new soundtrack stick, so I did what I always do when I’ve stumbled upon a new way to win. I got curious.

Why did it work?

Why did a coin help?

Why did something so small make such a big difference?

It took me months to find the answer, but when I did, it was so obvious.

It wasn’t a coin. It was a symbol. And the right symbol can work wonders for a soundtrack.

You’re Already Surrounded by Soundtracks

It took me forty-four years to learn what the best brands in the world have known for decades: symbols are a powerful way to cause action.

Don’t believe me? Okay, then why do you think people put Yeti stickers on their car to let you know their preferred method of keeping things cold? Did you ever see someone put an Igloo sticker on their car in the 1990s? No one did that, but Yeti found a way to transform their product into a symbol.

Owners who never talked about a cooler before are now eager to identify with the symbol of Yeti. Over burgers in the backyard, they will quickly tell you that their cooler can keep meat cold for ten days in a row.

Granted, if you’re ever in a situation where you are critically dependent on your ability to retrieve meat from a cooler and eat it nine days later, you probably have a bigger issue. There’s been an apocalypse but you haven’t been able to get to higher ground because your Yeti cooler is so heavy you can’t move it. If you have a few guns, you can hunker down in the garage and protect it from outlanders, because it’s also the most expensive thing you’ve ever purchased. The problem is that other survivors are going to know you have that cooler because you put a sticker on your car. At the time, it seemed like a good idea. How else would strangers know you were serious about portable refrigeration? Now, unfortunately, that sticker is just a beacon to other scavengers in the dystopian wasteland.

Yeti uses a sticker to encourage you to advertise their product on your car. Lululemon uses a logo to encourage you to buy their yoga pants. Nike uses a swoosh to ensure you hear the words “Just do it” without even reading them. Every successful brand in the world is serious about symbols because they know they work.

Symbols, and the meaning we attach to them, are powerful tools for living out our new soundtracks. The coins weren’t special. They’re small, an ugly color, and nearly useless. Good luck finding a vending machine in America that takes a dollar coin. I’ve looked, trust me. But none of that mattered, because the coin meant something to me.

Symbols, and the meaning we attach to them, are powerful tools for living out our new soundtracks.

It meant I was making my soundtrack true. It meant I wasn’t going to get another traffic ticket. It meant I was keeping my word to my wife. It meant I was being a good example for my kids. I grew to love hearing the sound those coins would make when they landed in the Mason jar. I liked looking at the progress as the jar filled up. I started volunteering to run more errands for my wife because then I could drive again and earn another coin.

It became a fun little game, and it turned out I wasn’t the only one playing it.

Turning the Finish Line into a Symbol

There’s a reason “dissertation” shares so many letters with “desert.” Both are lonely, boring places where dreams go to die. (Sorry, Arizona. You know I’m right. Turquoise jewelry can only do so much.) The first part of a doctoral program isn’t as isolating. There are more people involved in the coursework for the degree. You have professors, classmates, and a support network that moves you along.

But once you’re finished with that part of your degree, you head out into the wasteland of your dissertation. Those can drag on for years and years because you’re the only one pulling yourself toward the finish line. How do you know it’s done? How do you stay motivated? How do you make it a priority when the rest of life gets loud?

Those were the questions Priscilla Hammond was facing in 2014. Her coursework was completed, but now she found herself in the desert of the dissertation. She wanted it over. She wanted her doctorate but felt lonely and distracted in this new part of the project. One day she heard a talk about grit. It wasn’t just a talk, it was an invitation for her to start listening to a soundtrack: “I have the grit to finish my dissertation.”

That’s a great soundtrack, but listening once wasn’t going to work. When you put a single new soundtrack up against something as daunting as a dissertation, it doesn’t stand a chance.

Fortunately for Priscilla, the speaker did something smart that day. He brought a piece of finish-line tape for each audience member. He encouraged everyone to write on it what they were persevering toward. Priscilla didn’t have to think hard about hers: “I wrote Dr. Hammond.”

She wasn’t a doctor yet. That was still something in the future, but having that piece of tape added to the power of the new soundtrack. Internally, Priscilla was telling herself, “I persevere. I have grit. I finish dissertations.” Externally, she was reinforcing that with the piece of finish line. “See, it says it right there. Dr. Hammond. That’s going to happen.” She didn’t put the piece of tape in a drawer, because it’s harder to hear soundtracks when they are buried deep in a piece of furniture. “I stuck it up where I could see it at my desk,” she told me. It was a daily reminder of her finish line, a message in a bottle sent from the future.

It didn’t change the amount of work she had to do. Using positive symbols doesn’t mean you have to run fewer miles when you train for a marathon; it just means you might actually run them. Two years later, Priscilla finished her degree. “In 2016, I was able to write that [Dr. Hammond] as a fact, not a dream,” she told me. She’s now an assistant professor in South Carolina.

The tape was a symbol, and it worked for Dr. Hammond. Her story was just the tip of the iceberg though. When I started asking people if they used symbols, the stories came in droves.

Rocks, Reviews, and Tattoos

Everywhere I turned, I found people using symbols to make soundtracks stick.

Monica Tidyman, a library director from Stromsburg, Nebraska, has a rock on her desk. “My sisters-in-law and I hiked Fish Creek Falls at Steamboat, and it was a little tougher than we thought. At the top I picked up a rock and took it down to remind myself to never quit, because the beauty at the top is worth it.”

Monica could hope she remembered that. She could hope that in the millions of thoughts she’ll have every year, that one stuck out. She could cross her fingers that “Never quit, because the beauty at the top is worth it” will be the loudest soundtrack on the days she needs it most. Or she could grab a rock from the top of a mountain and put it on her desk as a reminder.

Erik Peterson, an author from Rialto, California, could hope he remembers his goals for his career, weight, marriage, and parenting. That’s a pretty long list, but maybe he could remember them. I sometimes open my phone and then forget why I did—like standing in front of a digital refrigerator you can’t remember the purpose of opening—but maybe Erik has a mind like a steel trap.

Or he could order dog tags engraved with all those soundtracks and wear them under his shirt every day. Guess which approach he’s had the most luck with?

LaChelle and Darren Hansen, a married couple from Linden, Utah, could try to be positive when they get rejection letters from literary agents. That’s part of the process of becoming a writer. You get rejected by agents, publishers, and strangers at book signings who decide $11 is too much for your life’s work. The Hansens could just have “better attitudes.” Or they could slap colorful stickers on each rejection letter that say “Good work!” and “Fantastic!” Then they could store all those rejection letters in a binder to help them remember that “rejection isn’t failure, and it’s not the end of a dream.” “Someday,” LaChelle promised me, “I will keep that binder on a bookshelf right next to all my published books.”

A rock is different from a binder, which is different from a dog tag. There are a thousand different ways to turn soundtracks into symbols, but the ones people have the most success with share three similarities.

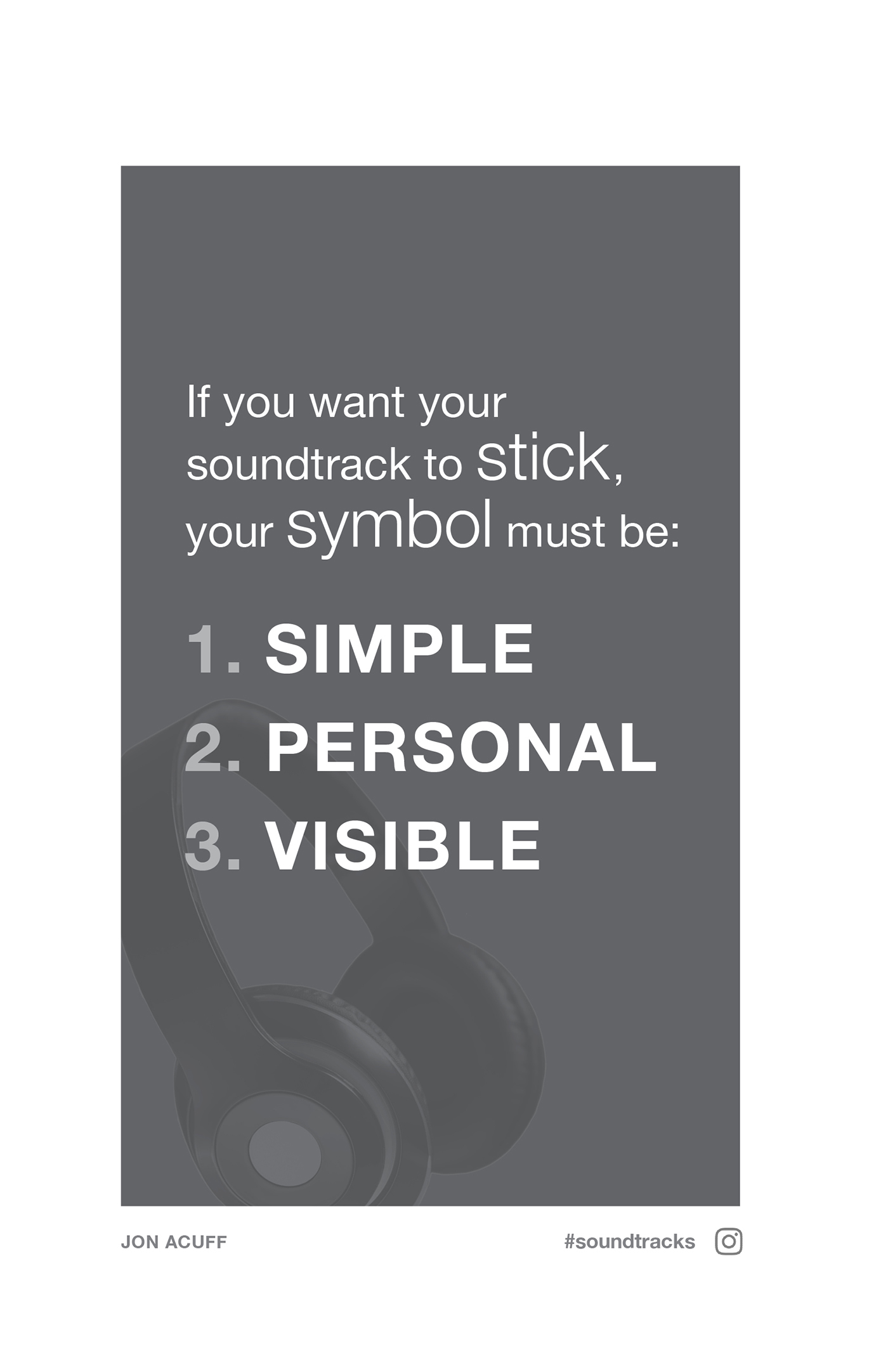

If you want your soundtrack to stick, your symbol must be:

- Simple

- Personal

- Visible

At least once a year, I almost get into bullet journaling. Originally created by Ryder Carroll, a digital product designer in Brooklyn, bullet journaling is supposed to be an easy way to track and plan your life. With an ordinary notebook you can work on your to-do list, your calendar, your expenses, the cycles of the moon, migratory patterns of birds, and a list of all the dogs you pet each month, complete with 3D illustrations created using Japanese felt-tip pens that cost more than the first car you purchased. It doesn’t even matter what kind of car it was, because I promise it was cheaper than pale-vermillion markers made from wild boar bristles found only in the lowlands of Mount Fuji.

What begins simply often mushrooms with complexity until I don’t use the notebook at all. This is the trap many symbols succumb to as well: the creation of the symbol proves more extensive than the benefit. To prevent that from happening to you, keep your symbol simple. Monica Tidyman picked up a rock from the ground. That was her entire symbol process. If you told me you weren’t creative enough to come up with your own symbol, I’d ask you if you lived near any rocks. The answer is probably yes. The planet is covered with them. Each layer of complexity you add to a symbol allows one more opportunity to get stuck overthinking. Cut that off at the pass by aiming for simple.

The symbol has to be personal, because you’re 100 percent of the people who will be using it. A symbol that works for your husband won’t work the exact same way for you. It has to reflect your unique soundtracks, not someone else’s. While reading through the above examples, I guarantee that at least once you thought, “That’s weird, I would never do that.” Of course not—those are someone else’s symbols. I personally wouldn’t do the rejection binder like LaChelle and Darren. Looking at tangible examples of rejection would be discouraging to me. Personally, I never feel motivated by reading my one-star reviews on Amazon. Some people do. Good for them. That’s their symbol, not mine.

Julie DenOuden, an elementary school teacher from Los Angeles, California, keeps a bag of lima beans on her desk. When she was in college, she had a professor whose husband was willing to paint lima beans for her first graders. It was a tedious, time-consuming task, but he did it because he loved his wife. That symbol stuck with Julie, and she realized she didn’t want to settle in her dating relationships. She wanted a husband who would 100 percent support her—a husband who would paint lima beans. Her dad bought her a bag, and every time she sees it, she remembers there are great guys out there. That’s such a perfect picture of a personal symbol.

Lastly, the symbol needs to be visible, because out of sight, out of mind. If you can’t easily see your symbol, then it’s not a symbol, it’s a souvenir. Like that funny shirt you got in Panama City Beach that says “Pineapple Willy’s.” It’s somewhere in a closet, forgotten the minute you got home and shook off the sand from that vacation. You need to see your symbol, especially in places where you’re prone to overthinking.

April Murphy, a music teacher in southeastern Michigan, uses photos of her family as a symbol. “I post a photo collage behind my computer at work so I can see my family supporting me. Overthinking for me only happens when I feel isolated.” That’s a surgical symbol right there. She’s attacking a specific cause of overthinking (isolation) with a symbol that combats it (her family photos).

If you can’t easily see your symbol, then it’s not a symbol, it’s a souvenir.

Your symbol needs to be on your desk, your fridge, your wrist, or even your body. Countless people turn soundtracks into tattoos as a way to forever emblazon some new decision. Paula Richelle Garcia, a photographer from Murrieta, California, has the word “joy” tattooed on the inside of her wrist. She says, “[It] reminds me that I get to choose how I am going to respond to every situation in my life.” It might only be three letters in ink, but she knows that “the more I have practiced stopping my negative thinking in its tracks and started finding something positive in the situation (which can be very hard in the beginning), the easier it has become.”

April Thomas, who described herself to me as “an auntie in Bel Air”—shout-out Fresh Prince—is a lot more blunt with the assessment of her tattoo. “I have a Bob Ross ‘Happy Tree’ tattoo,” she says. “It slaps me back to the positive when I find myself in the upside down.”

Sometimes the tattoo is an image, sometimes it’s a phrase, but the meaning is always the same: “This symbol matters to me so much that I want to be reminded of it for the rest of my life.” Talk about visible.

Do you know why the Lance Armstrong LIVESTRONG bracelets were so successful? Do you know why tens of millions of people wore them? Because they were simple, personal, and visible. Anyone can put on a bracelet—it doesn’t come with an instruction manual. “So you’re saying the arm part goes into this hole here? Run that by me one more time, please.” It also meant something important to the person wearing it. If you asked about the bracelet, people would say things like, “I wear this to support cancer research because my mom lost her life far too young.” I never met anyone who said, “I just don’t like cancer, the noun. I don’t personally know anyone who has been impacted; I’m just against diseases in general. Have you seen my eczema necklace?”

It was also extremely visible. Nike could have made it light gray. They could have made it a color that faded into the background a lot easier. They didn’t. They made it bright yellow on purpose. And so should you.

Just Pick One

Years ago, when Mike Peasley, PhD, and I did our initial survey to see if other people wrestle with overthinking, I was surprised how many people couldn’t finish it. It only took a few minutes to complete, but I got dozens of emails that said, “I only made it to question 3. I kept overthinking my answers.”

That’s probably the clearest sign that you’re an overthinker—you overthink the overthinking survey. I understand how that happens and recognize that it would be easy to overthink this moment too. You could spend hours, days, maybe even weeks kicking around what would be the perfect symbol for your new soundtrack. Or you could pick one from this handy list I put together for you and move on.

I bet you can find a symbol on that list that works for you. Now that you know what you’re looking for, I think you’ll be surprised to discover you’ve already been using one. Either way, strengthen the power of it by making it even more visible. A great way to do that is to share it online. Post it on Instagram with #soundtracks and tag me @JonAcuff so that I can cheer you on!

If You Find Me, I’ll Give You One of My Symbols

If you still can’t think of a symbol, come find me someday. I’m the ridiculously tall guy at the airport. When you do, I’ll give you the one that’s meant the most to me.

I loved that the dollar coins helped me quit texting while driving, but I didn’t really like the design of the coin. It wasn’t sexy at all. It felt like a dumb bronze quarter, not a symbol I wanted to keep in my pocket. That’s when I remembered something the teller at the bank asked me when I picked them up. He did a double take when I requested dollar coins and asked, “Did you mean half-dollar?” I was confused at his question and told him the dollar ones would be fine, but weeks later I realized he was right. I did mean half-dollar coins.

When’s the last time you saw one of those? They’re a lot bigger than you remember. They’ve got John F. Kennedy’s bust on them, there’s a special bicentennial design, and some of them actually contain real silver. When you hold one in your hand, it really feels like something. When you flip it, it really shines.

I called the bank back and ordered five hundred.

Was that too many? Probably.

When I picked them up, all the tellers gathered around to get a look at the weirdo who had come back for even more coins. What was he doing with them all? What did he know?

They brought the box of coins out from the vault, and I was surprised to find out there’d been a small mix-up. When I ordered five hundred, they thought I meant $500 instead of five hundred coins. The box they had for me contained one thousand half-dollars. If you thought five hundred coins was too many, you should have seen the twenty-four-pound miniature coffin of metal I walked out of Wells Fargo with that day. I weighed it when I got home. That’s not an exaggeration. That’s math.

I started carrying a half-dollar with me every day. I put them in my car. I put them on my desk. I gave them to friends. As I did, I discovered something.

A coin looks a lot like a dial. When my broken soundtracks get loud, it’s easy to take a coin out of my pocket and turn the dial down, reminding myself I don’t have to listen to that loud music anymore. It even looks like a tiny silver record in the right light. And if I ever need to come up with a new soundtrack, I can do what we learned in chapter 6 and flip over a broken one. It was a symbol. It was a dial. It was a record. It was exactly what I needed to stay connected to the new soundtracks, and it only cost fifty cents.

That’s the best news of all. You don’t need to order a thousand. The bank will give you one if you want. And if you lose it, guess what? You’re out fifty cents. I’ll even front you the first one. I’m generous like that. If you see me at a coffee shop, I’ll give you one. Trust me, I have PLENTY.

I’ll admit, a thousand coins was too many. I didn’t need that many. I’m glad I spent so much time working on my soundtracks though, because twelve years after that first message from the event planner, I got another one, and responding to it would require everything I’d learned about overthinking.