CHAPTER 11

I was in a rotten mood later that day as I sat in the kitchen eating the after-school snack Janet had fixed for me and scribbling angry, thick pen marks all over my sketch pad. I was annoyed with Daniel for caring more about his barely-a-soccer-team than he did about our future. And I was even more annoyed with him for being right: Nobody did seem interested in this election except for Janet and me. And as she and I started looking into what it actually took to run a successful political campaign, it was suddenly seeming like . . . a lot.

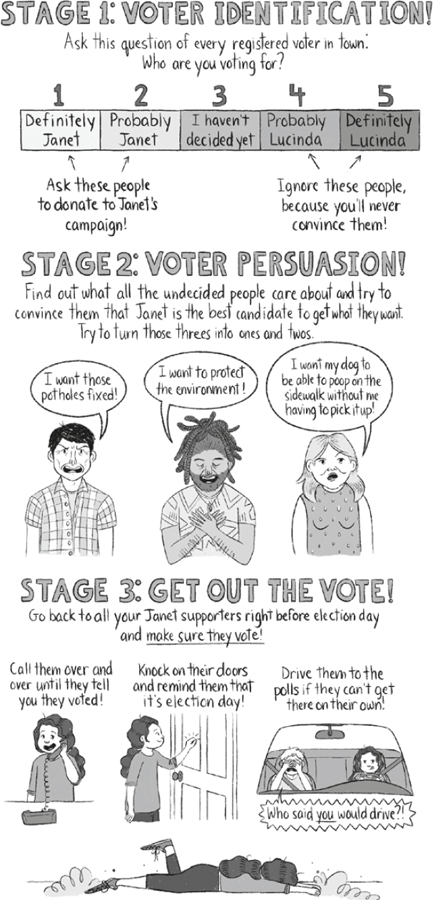

Janet had stepped outside to take a phone call, leaving me sitting alone with the information we’d found about the stages of a political campaign.

How exactly were we supposed to achieve all of that? Tens of thousands of voters lived in Lawrenceville. We’d never be able to reach them all. Especially considering there were only three of us working on Janet’s campaign. Really two and a half, since My Friend Daniel only kind of counted.

I threw my pen down and started to head outside to see if Janet was off her phone call so she could tell me what we should do. But I paused at the door when I heard her tone of voice. She sounded upset.

“I don’t know what to tell you,” I heard her say to whomever was on the other end. “It was a long time ago, and I was a lot younger then. I don’t think it has anything to do with who I am today.” She paused, listening. “Yes, I would,” she said, then paused to listen again. “Why? Because as mayor, I’d do what’s right for Lawrenceville. And if someone doesn’t want to vote for me because of a mistake I made when I was a kid, well . . . that’s their choice, I suppose, but I think that’s ridiculous.” She cleared her throat. “Yes,” she said. “Okay. Thanks for calling. Bye.”

She put her phone in her pocket and opened the door to come back inside. Then she saw me standing right there, looking at her.

“Hey, Maddie,” she said.

“What mistake did you make when you were a kid?” I asked. “Who was that? Are you okay? You sounded upset.”

She gave me a weak, unhappy smile. “That was a reporter from the Gazette. They heard . . . something about me, and they’re about to run a story about it, and they wanted to get a quote from me first.”

“What did they hear about you?” I asked. Whatever it was, clearly it was nothing good. But I couldn’t imagine what it might be. I’d known Janet since I was a little kid, and I’d never heard anything not-good about her. How could the Lawrenceville Gazette know something that I didn’t?

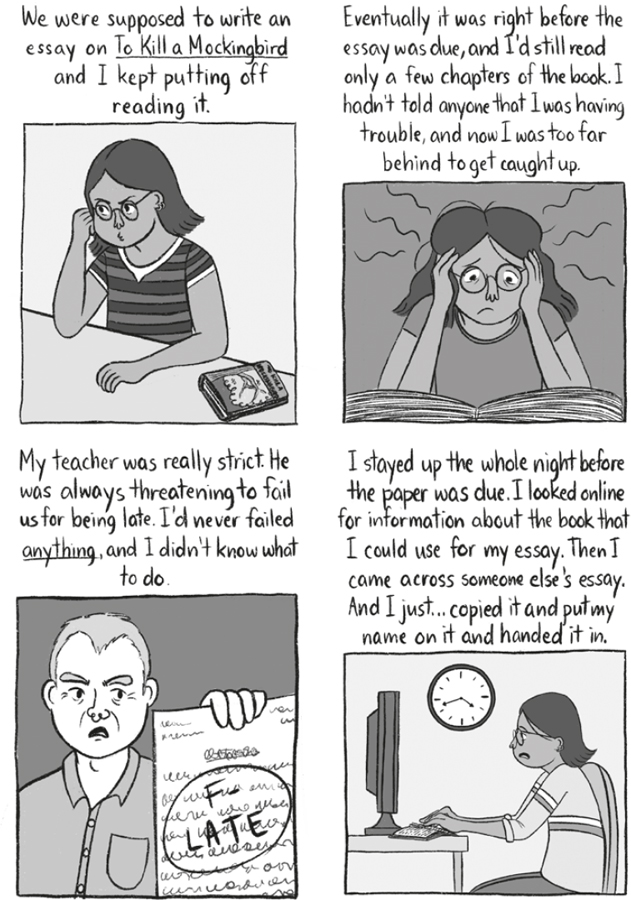

“Let’s sit down.” I followed Janet back into the kitchen and slid into the seat across from her. She rested her chin in her hands. “When I was fourteen,” she began, “I cheated in English class.”

“You did?” I jerked back to look at her.

She nodded. “Here’s what happened . . .”

“You plagiarized?” I whispered.

“Yes. Just that one time—not that it’s okay to do even once. The teacher checked everyone’s essays for plagiarism, so of course he caught me. He was angry, my parents were furious, and I felt so guilty. I failed the class.”

“How come I didn’t know about this?” I demanded.

“You were really little,” she reminded me.

“Yes, but how come you never told me since then?”

Janet sighed. “It was almost ten years ago. It has nothing to do with who I am today. I shouldn’t have done it, I made up for it, and I haven’t done anything like it since. It was a horrible decision, and I learned my lesson.”

“So how did the Gazette find out about it?”

“I imagine my old teacher told them when he heard that I was running for mayor. Or maybe someone else told the reporter—one of the other kids in my class, or one of the other teachers. A lot of people knew about it at the time, because I got in trouble and the school wanted to make an example of me. I don’t know how many of them would still remember and care about it a decade later.

“But now the Gazette is going to run an article about it. They talked to Lucinda before they called me, and she said that an unqualified cheater shouldn’t be mayor. She said that I didn’t do the work for that class, and I won’t do the work for our city. She said that she didn’t cheat at the Olympics. The reporter wanted to know if I had anything to say about any of that.” Janet closed her eyes, like it hurt to look at the world.

I felt like crying from frustration. “Why did you have to cheat?”

“I just told you,” she said. “I had poor judgment. I shouldn’t have—”

I felt like crying. Janet had betrayed me—she had betrayed me years ago, and I hadn’t even known it.

“I’m not perfect,” Janet said gently. “I never claimed to be. I cheated in school one time. I can’t find a job. I don’t have any money saved. I’m mean to my dad sometimes. I got a parking ticket a month ago and haven’t paid it yet. I’m not a terrible person, but I’m certainly not perfect.”

“But you’re supposed to be,” I repeated desperately.

“I wish I could be the person you want me to be, Maddie,” Janet said. “I love seeing myself through your eyes. You think I’m smart and brave and sophisticated and good at everything, and I want to be all of that for you. I don’t ever want to disappoint you.”

“So don’t disappoint me, then,” I muttered.

“Too late.” She rubbed her hands across her face. “Look, I didn’t tell you that I once plagiarized an essay because I didn’t want you to think any less of me, okay? I wanted you to keep seeing me the way you always have—as the person who can do anything, the superhero babysitter who can save the day, who can take on the bad guys, who could even become mayor. I wanted to be that person. But I’m just . . . not.”

“Does this mean you can’t be mayor?” I asked.

“Well, already probably nobody was going to vote for me except for my parents. Once this news gets out there . . . still nobody’s going to vote for me except for my parents.”

“Are you giving up?” She couldn’t be. Not when there was so much left to do. Not when I needed her. When all kids needed her.

“Maybe?” Janet said in a small voice.

I sucked in my breath. “The thing is, I didn’t really think about what it would mean to run for mayor. That all my private stuff, decisions I made years ago, would get dragged out into the spotlight for everyone to see and judge. It feels invasive and scary. I didn’t know it was going to be like this.

“I’m sorry I let you down,” Janet went on. “I’m sorry I let us both down. I would have liked to be mayor. But.” And then she didn’t say anything else. She didn’t have to.