CHAPTER 24

I stormed out of Jordan’s, my head down, hands in fists, and almost ran into the garbage man. “Hey, kid,” he said. He’d become a lot friendlier since I’d told him Janet wanted to increase the sanitation department’s budget and hire more people to work there.

“Hey,” I muttered, not looking at him. I knew I was being rude, but my eyes felt tense and hot, and I was worried that if I said more than a few words, I’d start crying. “Sorry,” I said. “I don’t really feel like talking.”

“Who feels like talking?” the garbage man asked. “I don’t feel like talking. Well, maybe I do, but I certainly don’t have time to talk. Do you have any idea how many stops I still have to hit today?”

I shook my head, averted my eyes, and tried to find a way around him.

“But you know what helps?” he said to me.

“What?” I mumbled.

“Knowing that it’s not forever. Knowing that when Janet gets elected, she’ll make this better.”

I finally looked up at him. Tears threatened to spill out of my eyes, but fortunately, the garbage collector didn’t seem to notice.

“It’s not just me,” he said. “Every garbage collector in this town is fed up with how we’re being treated. We’re all supporting Janet. We even got pins made. See?”

I stared at the pin. I didn’t really care how many people worked for the sanitation department. It had nothing to do with me. I wasn’t a garbage collector, I probably never would be, and the farthest I’d ever carried a trash bag was from my front door to the curb.

But this issue mattered to the garbage collectors just as much as art class mattered to me. They wanted a leader who would try to fix their problems just as much as I wanted a leader who would try to fix mine.

Maybe I could get Lucinda to add this to our deal. I’d tell her that we’d stop campaigning for Janet so long as she promised to give us arts education funding and sanitation department funding. She would probably agree to that. Right?

But then I started thinking about all the other people who’d asked Janet for so many other things over the course of this campaign. How Molly wanted more streetlights so she wouldn’t be scared walking in the evening, and Isabelle wanted high-speed internet, and Dylan’s sister wanted to be able to afford community college, and Theo’s dad wanted to be able to afford to buy a house. Everybody wanted something, and they were all depending on Janet to help them get it.

And who was I to say that art class mattered more than the rest of it?

Daniel had told me that I only thought about issues that directly affected me. Polly had told me that I judged other people for caring about things I thought were dumb and worthless. And I had told them both that they were wrong, because I didn’t want those things to be true.

But what if they were?

I could have a guarantee that my own life would get better if I started supporting Lucinda.

But I had a chance at making lots of lives better if I stayed with Janet.

I turned around and marched back into Jordan’s Hot House. Everyone looked up at me warily, like they thought I was going to yell at them again.

“Daniel,” I said, and he paused his game. “I’m sorry that I acted like your soccer team doesn’t matter. Dahlina”—she crossed her arms—“I’m sorry that I acted like your play and your Halloween costumes are dumb. Adrianne, I’m sorry that I’ve been calling you Molly like I don’t even care what your name is. I’ve been rude to all of you, and I’m going to try to do better.

“But you’ve laughed at me and called me names, and even though I try to act like I don’t care what anyone thinks of me, I can’t help but care. When people tell you all the time that you’re a weirdo, it makes you feel like one. When no one wants to hang out with you, it makes you feel like you’re not worth hanging out with. I’m sorry I’ve treated you badly. I think I was just trying to get revenge for the way you’ve treated me.”

And then something happened that I never would have expected: Holly spoke up.

“I’m sorry, too,” she said. “You’re different, but that’s not really a bad thing. In fact, maybe it’s a good thing, because only someone who’s different would have put together a campaign like this. If you weren’t different, Maddie, then nobody at all would be trying to stop Lucinda.”

“Whoa,” I said, staring at her. “You talk?”

She gave me a Holly Look.

“Oh, that was me being judgy, wasn’t it?” I realized. Everyone in the room nodded. “Sorry about that,” I said to Holly. “And thanks.”

“Look, we’ve spent a ton of time working together,” Polly/Dahlina told me, “and I’ve realized that maybe you’re not as weird as you seemed before I got to know you. Or, like, maybe you are that weird—but it’s a good weird.”

“I’ll take good weird,” I replied. “And now there’s something I need to do . . .”

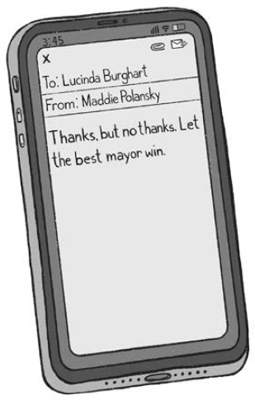

I pulled Lucinda’s business card out of my pocket and quickly sent her a message. Here’s what it said:

I didn’t care if she ever wrote me back.

My Friend Daniel clapped his hands. “Will you come to my bar mitzvah?!” he hollered at the room at large.

Everyone turned to look at him.

“What?” Molly/Adrianne asked.

“You know, now that we’re all friends,” Daniel explained.

Holly gave him a Holly Look.

“Hey, Daniel?” I said. “Let’s come back to that. Right now, we have a campaign to run.”

“I thought you said we shouldn’t even bother because there’s no way we can win,” Dahlina pointed out. “You said there’s nothing we have that Lucinda doesn’t.”

“Well,” I said, picking up her poodle skirt, “you made me think of one thing.”