FOOTWORK

and Yo-yoing of the Pelvis

When executed poorly, the Footwork exercise causes repeated rocking of the pelvis, which has an impact on the intervertebral disks.

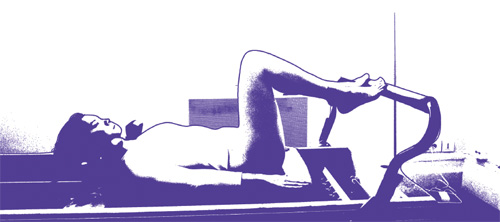

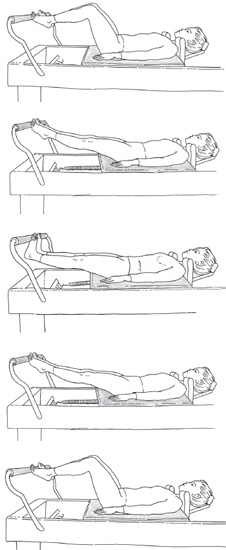

Starting Position

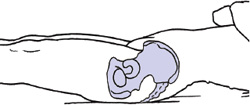

Lie on the carriage with the shoulders against the shoulder rests, the legs and feet parallel and a bit separated, the toes on the bar, and the knees flexed.

“Pilates position,” which is different from the position you see here, requires a slight external rotation of the legs. It’s desirable to alternate the positions (parallel and turned-out) in order to change the muscular engagement.

The Movement

This series progresses through different foot positions, with the arches and heels on the bar. Comparable to a plié in dance, the exercise engages the same three joints: the hips, the knees, and the ankles.

Extension of all three of these joints is required to push the carriage out, while flexion of the three joints is necessary to bring the carriage back in. During the return, the feet must maintain their force against the bar to resist the action of the springs.

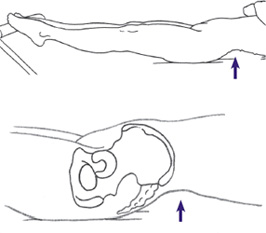

During the course of this exercise, the pelvis has a tendency to rock to the front and back in relation to the trunk (see box). This rocking is especially pronounced in the Tendon Stretch—the third Footwork variation depicted, which accentuates the forward tipping of the pelvis. Why?

Because the extension of the hips, knees, and ankles together tends to antevert the pelvis, while flexion of these three joints together tends to retrovert the pelvis. We therefore end up “scissoring” the pelvis back and forth repeatedly.

What we mean when we say that the pelvis “tips” forward or backward is that the pelvis moves in relation to a determined point of reference—the position wherein the iliac crests are perpendicular to the carriage and the ischia (sitz bones) aren’t touching the carriage. In this position the physiological curves of the spine are respected.

Extending the Legs Causes Anteversion of the Pelvis

Initially, we tend to use the pressure of the pelvis rather than the pressure of the feet against the bar. This causes us to flatten the lumbar spine against the carriage and bring the iliac spines toward the carriage—i.e., retroversion.

Then, when we start extending the legs, the opposite happens: the iliac spines move forward and the pelvis goes into anteversion, accentuating the lumbar curve. Why?

Anteversion is the tilting of the iliac crests forward—toward the ceiling if you’re on your back. Anteversion increases the lumbar curve.

The Ligaments at the Front of the Hip Pull the Iliac Crests Forward

Both the ligaments and the primary hip flexors—the psoas, iliacus, sartorius, rectus femoris, and tensor fascia latae—are put progressively under tension during the push-out phase of this exercise. When these ligaments and muscles are put under tension, they pull the iliac crests forward and the pelvis goes into anteversion. Dropping the heels under the bar increases the anteversion.

With the exception of the psoas, the primary hip flexors attach at the front of the iliac bone and are located on the anterior surface of the pelvis and the thigh. The psoas insertions are situated along the lumbar vertebrae. That said, stretching the psoas increases the curve of the lumbar spine and favors anteversion.

The Return: Leg Flexion Encourages Pelvic Retroversion

During the return movement, flexion of the hip increases, and the pelvis tends to roll the iliac spines backward; in other words, the pelvis goes into retroversion. Why?

Retroversion is the tilting of the iliac crests backward, which flattens the lumbar curve.

The Posterior Muscles of the Thigh Pull the Iliac Crests Backward

This time, it is not the anterior muscles of the thigh that are pulled, but the posterior muscles. Under tension, these muscles pull the iliac crests backward. The iliac spines move toward the carriage and the ischia move away from the carriage, reversing the anteversion. If the flexion goes beyond 90°, the pelvis is placed in retroversion.

Tilting the pelvis into retroversion leads to a flattening of the lumbar curve.

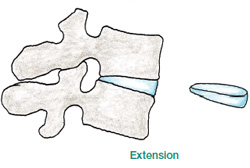

Tilting the pelvis into anteversion leads to an increase in the lumbar curve.

The Yo-yo Effect

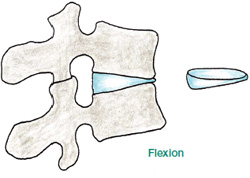

Flexion of the legs/anteversion brings the anterior surfaces of the vertebrae closer together: the front of the disk is squeezed and the back of the disk is stretched.

Extension of the legs/retroversion brings the posterior surfaces of the vertebrae closer together: the back of the disk is pinched while the front is stretched.

This back-and-forth play between retroversion and anteversion can cause “scissoring” of the lower intervertebral disks.

The intervertebral disks are very small cushions made up of fibrocartilage. They are interposed between the anterior parts of the vertebrae, known as the vertebral bodies, and they allow for movement of the spine in all directions. They also serve as shock absorbers for the spine.

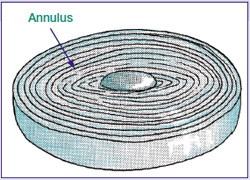

Each disk is composed of a fibrous ring—the annulus—that resembles the layers of an onion. The annulus encircles the gelatinous nucleus housed in the center.

These two components should remain stable for proper functioning of the disk. However, when the disk is damaged, fissures can form in the annulus and the nucleus can become unstable.

Why Is This Rocking a Risk Factor?

Lumbar flexion and extension are not harmful in and of themselves. However, the yo-yoing movement from one to the other tends to be too dramatic and can cause the posterior and anterior parts of the annulus to be too pinched and too stretched.

At the same time that the yo-yo effect is being produced, there is strong compression of the disk, in part due to the resistance of the springs. These factors combine to overwork the disk, especially the annulus, which is repeatedly “scissored.”

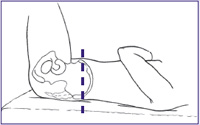

L5/S1: A Vulnerable Area

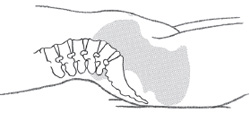

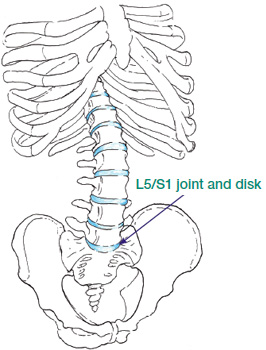

Among the lower intervertebral disks, the yo-yo effect has the greatest impact on L5/S1, situated between the top of the sacrum and the fifth lumbar vertebra.

The sacrum is the most posterior bone of the pelvis. Its lower end is joined to the coccyx, which is the lowest part of the vertebral column and is composed of five fused vertebrae. This area is easy to locate on yourself because it is convex and fits easily into your cupped hand.

This is the lowest disk; in the spinal column; therefore it’s the one that receives the most “load,” and is often overworked and fragile.

The sacrum and the lumbosacral disk on the sacral plateau

How to Stabilize the Pelvis During the Push-Out

We can prevent anteversion of the pelvis— and thereby prevent yo-yoing—by stabilizing it during the exercise.

1. Identify the Moment When the Pelvis Starts to Tip Forward

Repeat the exercise on the Reformer or on the mat. Starting with the pelvis in a neutral position and the knees a little bent, extend the legs out (glide the feet on the mat).

Notice when the pelvis starts to antevert.*1

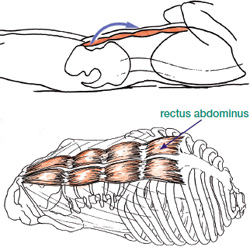

2. Use the Abdominal Muscles to Counteract Anteversion

Once we’ve identified the moment of anteversion, we can stabilize the pelvis with the abdominal muscles, specifically, the rectus abdominus. It’s this muscle that pulls the pelvis into retroversion and can therefore prevent it from moving in the opposite direction.

Finding the moment of anteversion in advance allows us to recruit the rectus abdominus at that moment and then regulate the amount of contraction needed throughout the exercise.

How to Stabilize the Pelvis on the Return

The pelvis can be kept in a neutral position on the return in order to avoid retroversion.

1. Identify the Moment When the Pelvis Tilts Backward

Try the exercise on the Reformer or on the mat without the bar and with your knees flexed.

Starting from a neutral pelvic position, draw the knees progressively toward the sternum. Notice the moment that the pelvis starts tilting backward into retroversion. It’s this tilting that we need to prevent.

2. Counteract Retroversion of the Pelvis

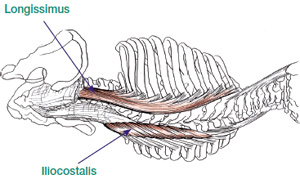

Once we’ve determined when the pelvis starts to retrovert, we can control it by recruiting the dorsal muscles—multifidus, interspinalis, longissimus, iliocostalis, and latissimus dorsi. These dorsal muscles are situated at the back of the trunk, along the spine, and along the ribs. They all oppose the action of the abdominals, and most of them bring the pelvis into anteversion.

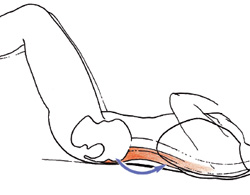

Alternating the action of the abdominals and the dorsals is a good way to control the position of the pelvis. Tracking exactly when the pelvis begins to tilt in either direction allows us to activate these muscle groups to keep the pelvis stable and above all to protect L5/S1. To control the movement of the pelvis even more, we can place a small cushion under the lumbar curve, which can help us to sense when the pelvis is stable. However, be careful not to crush or lift away from the cushion.

Other Exercises That Risk Yo-yoing the Pelvis

Reformer Exercises

There are several Reformer exercises that can destabilize the pelvis and lead to yo-yoing.

Hundred

During this exercise, be careful not to press your lower back into the carriage while trying to hold your legs in position. Also make sure that you don’t increase the lumbar curve when your legs are lowered.

Coordination

This exercise is a variation of the Hundred, and we find the same problems of pelvic instability.

Frog and Leg Circles

Follow the same precautions as in the previous exercises.

This is a lateral split, and we need to prevent the pelvis from moving toward either the front or the back. As in Footwork, when we push the carriage out, the pelvis tends to antevert, while on the return it tends to retrovert.

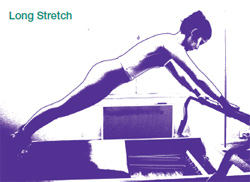

Long Stretch

Stabilize the pelvis throughout the whole exercise. The play between the abdominals and the dorsals is essential for keeping the heel-pelvisshoulder alignment.

Mat Exercises

The mat exercises that carry the risk of yo-yoing the pelvis include the following.

Hundred

This exercise is almost identical to the one performed on the Reformer. On the mat, however, the lack of springs reduces pressure on the lumbar area, and therefore reduces the risk of the yo-yoing.

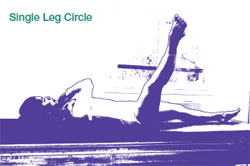

Single Leg Circle, Single Leg Stretch, Double Leg Stretch, Scissors, Crisscross, Double Leg Lower Lifts

Single Leg Circles, along with all of the exercises that follow—collectively called the “stomach series”—carry the same risk of pelvic instability and therefore the risk of weakening the lumbar disks.

Corkscrew

Turning the legs around the axis of the pelvis is a direct test of pelvic stability. Each time that the legs are moved away from and toward the pelvis, this instability is augmented.

Side Kick Series Front and Back, Bicycle, Rond de Jambe

This series specifically emphasizes the need for pelvic stability so that the pelvis doesn’t move forward when the leg goes to the front, and doesn’t rock backward when the leg goes to the back. This is an excellent opportunity to apply the principle of abdominal-dorsal engagement to prevent the yo-yo effect.