12

An Objective Theory of Historical Understanding

The different western philosophies are very largely variations on the theme of body–mind dualism. The main departures from this dualistic theme were attempts to replace it by some kind of monism. It seems to me that these attempts were unsuccessful. We find time and again that behind the veil of monistic protestations there still lurks the dualism of body and mind.

Pluralism and World 3

There were, however, not only monistic deviations, but also some pluralistic ones. This is obvious in polytheism, and even in its monotheistic and atheistic variants. Yet it may seem doubtful whether the various religious interpretations of the world offer an alternative to the dualism of body and mind, for the gods, whether many or few, are either minds endowed with immortal bodies, or else pure minds, in contrast to ourselves.

However, some philosophers have put forward a genuine pluralism, by maintaining the existence of a third world over and above mind and body, physical objects and conscious processes. These philosophers included Plato, the Stoics, and some modern thinkers such as Leibniz, Bolzano and Frege (but not Hegel, who embodied strong monistic tendencies, although he often speaks of an ‘objective mind’ or ‘spirit’).

Plato’s world of Forms or Ideas was not a world of consciousness nor of the contents of consciousness, but rather an objective, autonomous third world of logical contents. It existed alongside the physical world and the world of consciousness as a third, objective and autonomous world. I wish to defend this pluralistic philosophy here, even though I am neither a Platonist nor a Hegelian.

In this philosophy our world consists of at least three distinct sub-worlds; or, as I shall say, there are three worlds. The first is the physical world or the world of physical states; the second is the world of consciousness or the world of mental states; and the third is the world of ideas in the objective sense. It is the world of theories in themselves, and their logical relations; the world of arguments in themselves; and of problems in themselves, and problem situations in themselves. On the advice of Sir John Eccles, I have called the three worlds ‘world 1’, ‘world 2\ and ‘world 3’.

One of the fundamental problems of this pluralistic philosophy concerns the relationship between these three worlds.

The three worlds are so related that world 1 and world 2 can interact and so can world 2 and world 3. This means that world 2, the world of subjective or personal experiences, can interact with each of the other two worlds. It appears that world 1 and world 3 cannot interact, save through the intervention of world 2, the world of subjective or personal experiences.

It seems to me important that the relationship of the three worlds can be described in this way – that is, with world 2 as the mediator between world 1 and world 3.

It was the Stoics who first made the important distinction between the world 3 and objective logical content of what we are saying, and the objects about which we are speaking. These objects, in their turn, can belong to any of the three worlds: we can speak first about the physical world (either about physical objects or about physical states) or second about psychological states (including our grasp of theories) or third about the logical content of theories, such as some arithmetical propositions, and especially about their truth or falsity.

It is important that the Stoics extended the theory of world 3 from Platonic ideas to theories and propositions. However, they also included still other world 3 linguistic entities such as problems, arguments and investigations; and they made further distinctions between such objects as commands, admonitions, prayers, treaties and narratives. They also drew a very clear distinction between a personal state of sincerity or truth and the objective truth of theories or propositions; that is to say, theories or propositions to which the world 3 predicate ‘objectively true’ applies.

I wish now to distinguish between two groups of philosophers. The first consists of those who, like Plato, accept an autonomous world 3 and look upon it as superhuman and consequently as divine and eternal.

The second group consists of those who, like Locke or Mill or Dilthey, point out that language, and what it ‘expresses’ or ‘communicates’, is man-made. For this reason, they see language and everything linguistic as a part of the first two worlds and reject the suggestion of a world 3. It is very interesting that most students of the humanities, especially historians of culture, belong to this second group, which rejects world 3.

The first group, the Platonists, are supported by the fact that there are eternal verities: an unambiguously formulated proposition is, timelessly, true or false. This seems to be decisive: eternal verities must have been true before man existed. Thus they cannot be of our making.

The philosophers of the second group agree that such eternal verities cannot be of our own making; yet they conclude from this that there are no eternal verities.

I think that it is possible to adopt a position which differs from that of both these groups. I suggest that we should accept the reality and especially the autonomy of world 3, that is to say, its independence from human whim, whilst at the same time admitting that world 3 originated as a product of human activity. One can admit that world 3 is man-made and, in a very clear sense, superhuman at the same time.

That world 3 is not a fiction but exists ‘in reality’ will become clear as soon as we consider its tremendous effect on world 1, mediated through world 2. One need only think of the impact of the theory of electrical power transmission or atomic theory on our inorganic and organic physical environment, of the effect of economic theories on decisions such as whether to build a boat or an aeroplane.

According to the position which I am adopting here, world 3, like human language, is the product of men, just as honey is the product of bees. Like language (and, I presume, like honey), world 3 is also an unintended and unplanned by-product of human (or animal) actions.

Let us look, for instance, at the theory of numbers. I believe (unlike Kronecker) that the series of natural numbers is the work of men, the product of human language and of human thought. Yet there is an infinity of such numbers, and therefore more, infinitely more, than will ever be pronounced by men, or used by a computer. And there is an infinite number of true equations between such numbers, and of false equations; more than we can ever pronounce as ‘true’ or ‘false’. They are all inhabitants, objects, of world 3.

But what is even more interesting, new and unexpected problems arise as unintended by-products of the sequence of natural numbers; for instance the unsolved problems of the theory of prime numbers (Goldbach’s conjecture, say). These problems are clearly autonomous. They are independent of us; rather, they are discovered by us. They exist, undiscovered, before their discovery. Moreover, at least some of these unsolved problems may be insoluble.

In our attempts to solve these or other problems we may invent new theories. These theories are produced by us: they are the product of our critical and creative thinking. But the truth or falsity of these theories (of Goldbach’s conjecture, for instance) is not of our making. And each new theory creates new, unintended and unexpected problems, autonomous problems, problems to be discovered.

This explains how it is possible for world 3 to be our product by origin, although it is in another sense at least partly autonomous. It explains why we can act upon it, and add to it or help its growth, even though there is no man who can master even a small corner of this world. All of us contribute to its growth, but almost all our individual contributions are extremely small. All of us try to grasp it, and none of us could live without interacting with it, for all of us make use of language.

Yet world 3 has grown far beyond the grasp not only of any man, but even of all men, in a readily comprehensible manner.1 Its action upon our spiritual growth and at the same time upon its own growth is even greater and more important than our very important creative action upon it. For almost all spiritual growth in mankind is due to a feedback effect: our own intellectual growth and the growth of world 3 result from the fact that unsolved problems require us to attempt solutions; and since many problems will always remain unsolved and undiscovered, there will always be scope for original and creative work, although – or precisely because – world 3 is autonomous.

The Problem of Understanding, Especially In History

I have given here some grounds which support and explain the theory of the existence of an autonomous world 3 because I hope to bring all this to bear upon the so-called problem of understanding. This problem has long been regarded by students of the humanities as one of their central problems.

I want to make brief reference here to the theory that it is the understanding of objects belonging to world 3 which constitutes the chief task of the humanities. This, it appears, is a radical departure from the fundamental dogma accepted by almost all students of the humanities and particularly by most historians, and especially by those who are interested in the problem of understanding. I mean the dogma that the objects of our understanding belong to world 2 as the products of human actions and that, consequently, they are mainly to be understood and explained in psychological (including social psychological) terms.

Admittedly, the act or process of understanding contains a subjective or personal or psychological element. But the act must be distinguished from its more or less successful outcome: from its (perhaps only provisional) result, the obtained understanding, the interpretation, with which we must work on a trial basis, and which we can try to improve further. The interpretation may in its turn be regarded as a world 3 product of a world 2 act, but also as a subjective act. But even if we regard it as a subjective act, there is in any case still a world 3 object which corresponds to that act. In my opinion this is important. Regarded as a world 3 object, the interpretation will always be a theory: take, for example, a historical interpretation, a historical explanation. This may be supported by a chain of arguments as well as by documents, inscriptions and additional historical pieces of evidence. So the interpretation proves to be a theory and, like every theory, it is anchored in other theories, and in other world 3 objects. And in this way the world 3 problem of the merits of the interpretation can be raised, and especially its value for our understanding.

But even the subjective act of understanding can be understood, in its turn, only through its connections with world 3 objects. For I assert the following three theses concerning the subjective act of understanding:

that every such act is anchored in world 3;

that almost all important remarks which can be made about such an act consist in pointing out its relations to world 3 objects; and

that such an act consists in nothing other than the fact that the way in which we operate with world 3 objects closely resembles the way in which we operate with physical objects.

A Case of Objective Historical Understanding

All this is especially true for the problem of historical understanding. The main aim of historical understanding is the hypothetical reconstruction of a historical problem situation.

I will try to illustrate this theory with the help of a few (necessarily brief) historical remarks upon Galileo’s theory of the tides. This theory has turned out to be ‘unsuccessful’ (because it denies that the moon has any effect on the tides), and even in our own time Galileo has been severely and personally attacked (by Arthur Koestler) for sticking obstinately to such an obviously false theory.

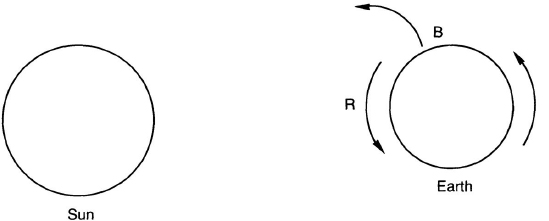

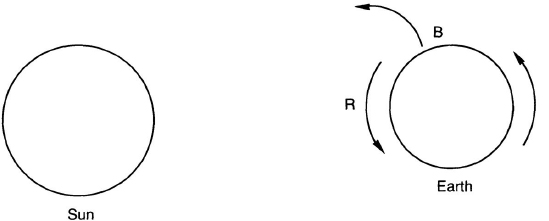

In brief, Galileo’s theory says that the tides are a result of accelerations which, in their turn, are a result of the movements of the earth. When, more precisely, the regularly rotating earth is moving round the sun, then the velocity of any surface point located on the side opposite the sun will be greater than the velocity of the same point when it faces the sun. (For if B is the orbital velocity of the earth and R is the rotational velocity of a point on the equator, then B + R is the velocity of this point at midnight and B – R its velocity at midday.) These changes in velocity mean that there must arise periodic accelerations and retardations. But any periodic retardations and accelerations of a basin of water result, says Galileo, in appearances resembling those of the tides. (Galileo’s theory is plausible but incorrect in this form: apart from the constant acceleration due to the rotation of the earth – that is, the centripetal acceleration – which also arises if B is zero, there does not arise any further acceleration and therefore especially no periodic acceleration.2

What can we do to improve our historical understanding of this theory, which has so often been misinterpreted? I claim that the first and all-important step is to ask ourselves: what was the third-world problem to which Galileo’s theory was a tentative solution? And what was the situation – the logical problem situation – in which this problem arose?

Galileo’s problem was, quite simply, to explain the tides. Yet his problem situation was far less simple.

It is clear that Galileo was not even immediately interested in what I have just called his problem. It was another problem which led him to the problem of the tides: the problem of the movement of the earth, the problem of the truth or falsity of the Copernican theory. It was Galileo’s hope that he would be able to use a successful theory of the tides as a decisive argument in favour of the Copernican theory.

What I call Galileo’s problem situation turns out to be a complex affair. The problem situation entails the problem of the tides, but in the specific role of a touchstone of the Copernican theory. Yet even this does not suffice for an understanding of Galileo’s problem situation.

As a true cosmologist and theoretician Galileo was first attracted by the incredible daring and simplicity of Copernicus’ main idea, the idea that the earth and the other planets are, so to speak, moons of the sun.

The explanatory power of this bold idea was very great; and when Galileo discovered the moons of Jupiter through his telescope and recognized in them a small model of the Copernican solar system, he saw in this an empirical corroboration of this bold and almost a priori idea. In addition, he succeeded in testing a prediction derivable from Copernicus’ theory: it predicted that the inner planets would show phases, like those of the moon; and Galileo discovered the phases of Venus.

Copernicus’ theory was essentially a geometric-cosmological model, constructed by geometrical (and kinematical) means. But Galileo was a physicist. He knew that the real problem was to find a mechanical physical explanation; and he discovered some important elements of such an explanation, especially the law of inertia and the corresponding conservation law for rotary motions.

Galileo tried to base his physics on just these two laws (which he probably took to be one law), although he was aware that there must be great gaps in his physical knowledge. From the point of view of method Galileo was perfectly right; for only if we try to exploit our fallible theories to the limit can we hope to learn from their weaknesses.

This explains why Galileo, in spite of his acquaintance with the work of Kepler, stuck to the hypothesis of circular motion; and he was quite justified in doing so. It is often said that he tried to cover up the difficulties of the Copernican cycles, and that he oversimplified the Copernican theory in an unjustifiable manner; also that he ought to have accepted Kepler’s laws. But all this shows a failure of historical understanding– an error in the analysis of the third-world problem situation. Galileo was quite right to work with bold oversimplifications; and Kepler’s ellipses were equally bold oversimplifications. But Kepler was lucky because his oversimplifications were later used, and thereby explained, by Newton, and so became a test of his solution of the two-body problem.

But why did Galileo deny the influence of the moon in his theory of the tides? This question opens up a highly important aspect of the problem situation. First, Galileo was an opponent of astrology, which identified the planets with the gods; in this sense he was a forerunner of the Enlightenment and an opponent of Kepler, although he admired him.3 Second, he worked with a mechanical conservation principle for rotary motions, and this appeared to exclude interplanetary influences. Galileo’s method in making a serious attempt to explain the tides on this narrow basis was perfectly correct, for without this attempt we could never have known that this basis was too narrow to provide an explanation, and that a further idea was needed – Newton’s idea of attraction and long-distance effect; an idea which had an almost astrological character and which was felt to be occult by proponents of and adherents to the Enlightenment (including Newton himself).

Thus we are led by the analysis of Galileo’s problem situation to a rational explanation of Galileo’s method in several points in which he has been criticized by various historians; and thus we are led to a better understanding of Galileo. Psychological explanations, such as ambition, jealousy, the wish to create a stir, aggressive disposition and ‘obsession’ with a fixed idea, become superfluous.

Similarly it becomes superfluous to criticize Galileo for ‘dogmatism’ when he adhered to the circular movement, or to introduce the ‘mysterious circular movement’ (Dilthey) as an archetypical idea, or perhaps to try to explain this idea by psychologal means. For Galileo’s method was correct when he tried to proceed as far as possible with the help of a rational conservation law for rotary motions. (No dynamic theory existed as yet.)

Generalization

In place of psychological explanatory principles we make use of third-world considerations mainly of a logical character; and this is the cause of the growth in our historical understanding.

This third-world method of historical understanding and explanation may be applied to all historical problems; I have called it the ‘method of situational analysis’ (or of ‘situational logic’).4 It is a method which, wherever possible, replaces psychological explanations by third-world relations of an essentially logical nature as the basis of historical understanding and explanation, including the theories and hypotheses that were assumed by the acting persons.

The thesis I wanted to present here can be summarized as follows: historical understanding should abandon its psychologizing methods and adopt a method built upon a theory of world 3.5

Notes

1 For it can be shown (A. Tarski, A. Mostowski, R. M. Robinson, Undecidable Theories, Amsterdam, 1953; see especially note 13 on pp. 60 ff.), that the (complete) system of all true propositions in the arithmetic of integers is not axiomatizable and is (essentially) undecid able. It follows that there will always be infinitely many unsolved problems in arithmetic. It is interesting that we are able to make such unexpected discoveries about world 3, completely independent of our state of mind. (This result essentially goes back to the pioneer work of Kurt Gödel.)

2 One might say that Galileo’s kinematic theory of the tides contradicts the so-called Galilean relativity principle. But this criticism would be false, historically as well as theoretically, since this principle does not refer to rotational motion. Galileo’s physical intuition – that the rotation of the earth has non-relativistic mechanical consequences – was right; and although these consequences (the motion of a spinning top, Foucault’s pendulum, etc.) do not explain the tides, the Coriolis force at least is not quite without influence upon them. Also, we get periodic kinematical accelerations as soon as we take into account the curvature of the earth’s movement round the sun.

3 See my Conjectures and Refutations, 1963 (12th impression, Routledge, London, 1990), p. 188, in which I show that Newton’s gravitational theory- the theory of the ‘influence’ of the planets upon each other and of the moon upon the earth – was taken from astrology.

4 See my books The Poverty of Historicism, 1957 (14th impression, Rout- ledge, London, 1991), and The Open Society and Its Enemies (14th impression, Routledge, London, 1991–2), 1945.

5 This makes so-called ‘hermeneutics’ superfluous, or at least simplifies them.

An extended version of a lecture given on 3 September 1968 in the plenary session of the XIV International Congress for Philosophy in Vienna (see also my essay ‘On the Theory of the Objective Mind’, reprinted as chapter 4 of Objective Knowledge, Oxford University Press, 1972, 1979).