Chapter 25

Plot

What keeps a reader reading?

Howard Campbell, the narrator of Mother Night, clues us in:

I froze.

It was not guilt that froze me.…

It was not a ghastly sense of loss that froze me.…

It was not a loathing of death that froze me.…

It was not heartbroken rage against injustice that froze me.…

It was not the thought that I was so unloved that froze me.…

It was not the thought that God was cruel that froze me.…

What froze me was the fact that I had absolutely no reason to move in any direction. What had made me move through so many dead and pointless years was curiosity [italics mine].294

That’s the same thing that keeps a reader reading.

Plot—the very concept, and the structure of any plot—relies on the reader’s curiosity.

Vonnegut’s “Creative Writing 101” Rule #3:

Every character should want something, even if it is only a glass of water.295

Wanting something, anything, triggers curiosity. And suspense. Will the character get what she desires or not?

Kurt told us in class that even a small problem would keep a reader reading. A nun in our workshop wrote a story in which her character, also a nun, had a piece of dental floss stuck in her teeth all day. Would she ever get it out? Kurt was delighted with that. He used that detail to talk about suspense and plot forever after. I think he was amazed that his own curiosity about the stuck floss pulled him along in the story.

Nobody could read that story without fishing around in his mouth with a finger.… When you exclude plot, when you exclude anyone’s wanting anything, you exclude the reader, which is a mean-spirited thing to do.296

More complex, vital things may be occurring—the nun may be battling cancer or want to break out of her habit, for example—but this basic will-she-or-won’t-she-get-what-she-wants is the scaffold upon which those complexities can be built.

Vonnegut says,

I guarantee you that no modern story scheme, even plotlessness, will give a reader genuine satisfaction, unless one of those old-fashioned plots is smuggled in somewhere. I don’t praise plots as accurate representations of life, but as ways to keep readers reading.

Vonnegut gives some examples of “those old-fashioned plots”:

Somebody gets into trouble, and then gets out again; somebody loses something and gets it back; somebody is wronged and gets revenge; Cinderella; somebody hits the skids and just goes down, down, down; people fall in love with each other, and a lot of other people get in the way; a virtuous person is falsely accused of sin; a sinful person is believed to be virtuous; a person faces a challenge bravely, and succeeds or fails; a person lies, a person steals, a person kills, a person commits fornication.297

A single, core conflict is at the heart of the structure of a story.

No conflict equals no plot.

Motivation and conflict are the engines that initiate a story, keep it moving, and form its particular shape.

In my first creative writing class at the University of Arkansas, my teacher, the writer William Harrison, drew the shape of a classic short story plot on the blackboard. It consisted of two lines, like the sides of an isosceles triangle: the longer side zigzagged up to a pinnacle, and the shorter side fell straight part way down from that topmost point. Such an illustration can now be found in creative writing texts.

To put it academically: plot consists of exposition, complications or rising action, climax, and denouement.

Exposition plants the conflict. The stakes intensify through complications and obstacles. The turning point or climax happens when the conflict comes to a head: an insight or epiphany occurs, a decision is made, and/or an action takes place that resolves or comes to terms with the basic conflict. The denouement is the final curtain.

A classic short story is like a geometry proof. Or like a sneeze. Ah-ah-Ah-aH-AH-AH-CHOO! with a little spray of recovery at the end. Or orgasm.

The twists and turns take up most of a story.

You can put [the reader] to sleep by never having characters confront each other.… It’s the writer’s job to stage confrontations, so the characters will say surprising and revealing things, and educate and entertain us all. If a writer can’t or won’t do that, he should withdraw from the trade.298

Vonnegut’s “Creative Writing 101” Rule #6:

Be a sadist. No matter how sweet and innocent your leading characters, make awful things happen to them—in order that the reader may see what they are made of.299

And to lure the reader into turning pages.

“Curiosity killed the cat,” my mother used to say. After a pause, she’d add, “But satisfaction brought it back to life again.”

Whether gambling, watching a ballgame, or reading a mystery, according to researchers, “people are invested in learning the outcome… but they do not wish to learn the outcome too quickly.”300

They also need signposts and reminders.

And you’ve got to give your reader familiar props along the way. In Alice in Wonderland, remember, when she’s falling down the hole there are all these familiar, comforting objects along the sides: cupboards and bookshelves and maps. Orange marmalade.301

Special attention should be given to the state of good or ill fortune of the focal character or characters at the beginning of a tale, and again at the end. The story-teller will customarily help, will emphasize the high, low, or medium condition of his characters at crucial points [italics mine].302

Sometimes you need to repeat, by summarizing what’s happened already through a character’s recollection or some other means, to keep the reader attuned to the stakes, and to up the ante.

According to Sidney Offit, “[Kurt] said the only thing you can teach is development. A story has to have a development and change.”303

That’s what the zigs and zags of plot are all about.

The most entertaining and informative discussion of the subject you’ll ever see is Vonnegut on YouTube, graphing the shapes of stories.

How that video came about is a story in itself. It has a plot. I hope to tell the story and at the same time to inform more about Vonnegut’s plot tactics.

It starts like this: once upon a time, for his master’s thesis in 1947 at the University of Chicago (see chapter 3), Vonnegut put forth the theory that a culture’s myths are like other anthropological artifacts, and should be considered so by anthropologists. He focused on the formation of new myths during rapid change, specifically North American Indian narratives.

The thesis was rejected. He dropped out and never got the degree.

Nearly twenty years later, in 1965, when first at the University of Iowa, he tried again. Let’s say, for this story’s motivation’s sake, that he wanted a degree more than ever, because in teaching at a university for the first time, surrounded by academics and writers with college degrees, he felt the lack of one more acutely.

All he needed was the thesis. So he wrote another: “Fluctuations Between Good and Ill Fortune in Simple Tales.” Its theme is the same as his first, but this time he argues that the shapes of all stories can be considered cultural artifacts. It opens with this assertion:

The tales man tells are among the most intricate and charming and revealing of all his artifacts.

He analyzes a D. H. Lawrence story, “Tickets, Please,” to prove his ideas, reproducing it completely. It takes up half his thesis. It “had to be set down in its entirety,” he explains. Because “offering only fragments,” like chips of a smashed vase, would not have revealed “its form.”

What makes it a cultural treasure is precisely what has been neglected by anthropologists: how the tale is told.

Alluding to the scientific method, he says,

It is possible… to make a… useful analysis of any tale’s form… in such a way that other investigators making independent analyses of the same tale will arrive at conclusions much the same.

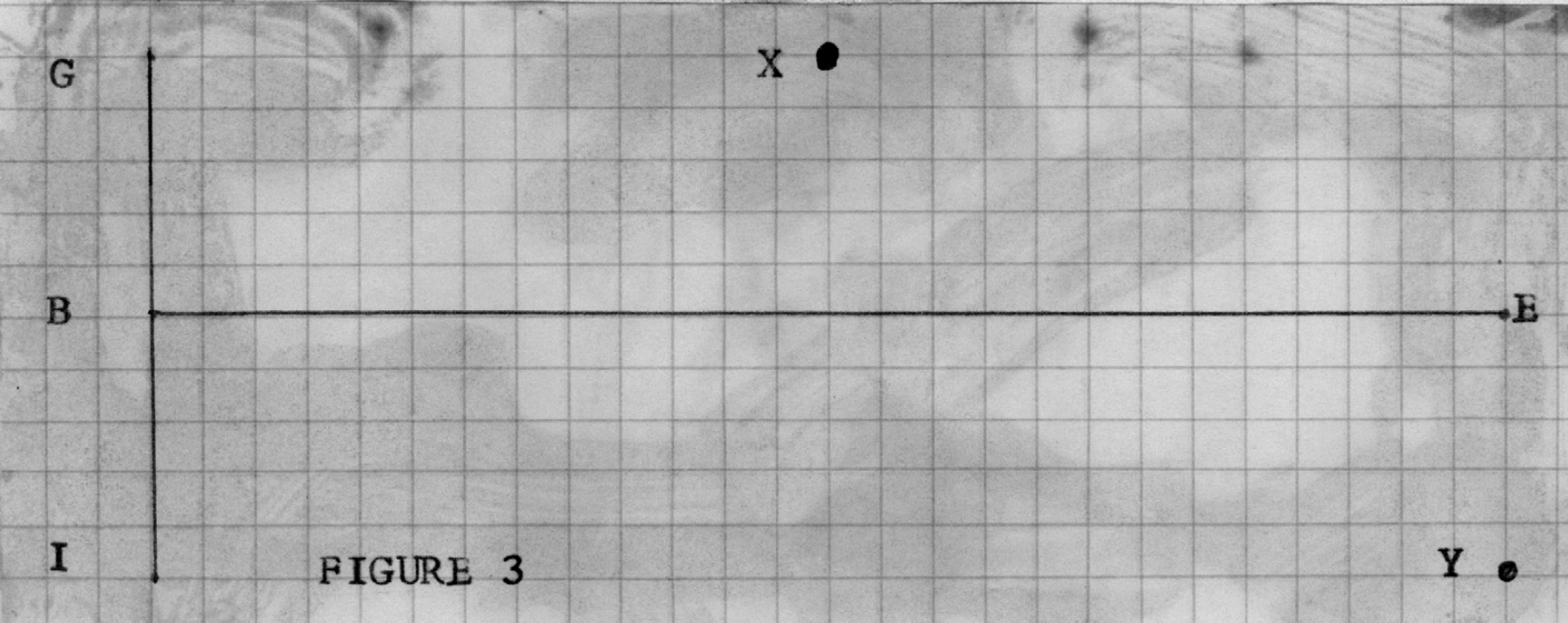

He presents a two-line chart. A vertical line is on the left side. A horizontal line starts halfway up the vertical and crosses the page:

The vertical scale represents “degrees of good and ill fortune… with good at the top and ill at the bottom, and with a null at its middle, averageness, or perhaps sleep.” The horizontal designates a life-as-usual neutral place, upon which Vonnegut illustrates the characters’ fortunes fluctuating up and down.

It can be seen now that… the fluctuations between good and ill fortune in large measure determine form.

For graphic purposes, a tale begins when its focal character or characters experience changes in fortune, and it ends when those fluctuations cease. All else is background.

… A contemporary master story teller cares deeply about the form of his tales because he is obsessed with being entertaining, with not being a bore, with leaving his audience satisfied.

There is a well-known credo for modern tale-tellers who wish to be loved, and I am unable to identify its author, but it goes roughly like this: “A story-teller must tell his story in such a way that the reader will not feel that his time has been wasted.”

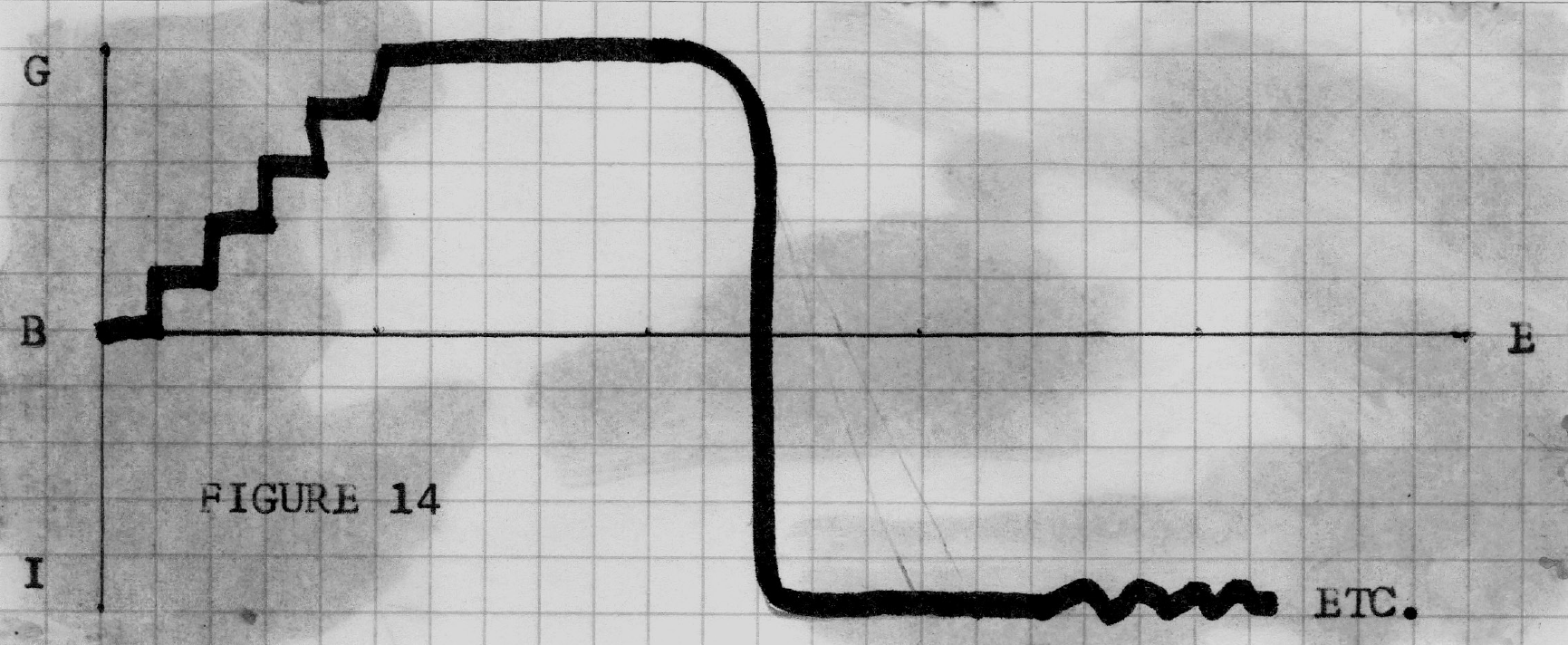

Within the text, Vonnegut illustrates several classic plots and unusual modern ones. “The Ugly Duckling,” “the simplest formula of all,” looks like a set of stairs. Kafka’s The Metamorphosis starts at neutral and plunges below the horizontal line, never to rise above it again.

The biblical story of Genesis he calls a “remarkably formed artifact”:

It begins like nearly all the other creation myths… with the “Ugly Duckling” curve.… But look at what some tale-telling genius did when he reached the top of the steps in Genesis… : He caused Adam and Eve to be expelled from the perfect universe which he had just created for his audience.

He wraps the thesis up with these fancy remarks:

The graphic method above brings the skeleton of any tale into the open, where it can, as a skeleton, be examined and discussed with some objectivity.…

It is my hope that such literary skeletons will be of interest to anthropologists, who are used to working with bare bones.

There’s an appendix: “Simple Skeletons of 17 Tales Chosen from Sharply Diverse Sources.”304 It consists of penciled illustrations on cheap, pale-green graph paper. They’re kind of thumbing-your-nose hilarious.

Although striving once more to persuade anthropologists that the forms of stories are artifacts as fetching and worthy of examination as any others in a culture, the anthropology department at the University of Chicago rejected his thesis. Again.

Of course they did! Half of it is a reprinted story. The language is informal and nonacademic. The last line is Vonnegut at his whimsical best. Although he does ask provocative questions about stories’ cultural implications (such as wondering about editors’ insistence in the ’50s that stories begin with people “in comfortable circumstances” and conclude with them being “even more comfortable at the end”), this thesis emphasizes the shapes of plot rather than how those shapes are artifacts.

His response at the time to this second rejection: “They can go take a flying fuck at the moooooon.”305

Meanwhile, at Iowa he was teaching the points he was making about storytelling. Robert Lehrman remembers, “In class, Kurt had annoyed some students by boiling all fiction down to a diagram: ‘Get someone in trouble. Get them out!’ he would say. ‘Man-in-the-hole!’”306

Then Vonnegut’s fortunes soared. He gained acclaim. Six years after turning his thesis down, the University of Chicago decided Cat’s Cradle sufficed as a thesis and in 1971 bestowed upon him an honorary degree.

As time went on, he lectured on the shapes of stories, illustrating them as he did in his thesis, but live, in person, on a chalkboard.

To top this success story off, that lecture, based on his rejected thesis, is now the marvelously engaging and instructive one you can see on YouTube.

Vonnegut’s gone. But the bare bones of his thesis live on.

End of story.

Talk about desire, disappointment, conflict, surprise, and triumph!

But let’s return to that place where a character’s fortune takes a decided shift. That turning point or climax can be internal—a character has a change of heart or a realization. It can be external—something happens that forces the conflict to come to a head. It can be both—a character becomes aware or makes an internal decision, then acts upon it.

In this scene from God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater, Eliot Rosewater is being questioned by his friend Charley, who thinks he’s gone bonkers. Noyes Finnerty, a janitor who’s sweeping up nearby, has been eavesdropping.

Noyes Finnerty spoke up. “All he hears is the big click.” He came forward for a closer examination of Eliot.… “He heard that click, man. Man, did he ever hear that click.”

“What the hell are you talking about?” Charley asked him.

“It’s a thing you learn to listen for in prison.”

“We’re not in prison now.”

“It ain’t a thing that happens just in prison. In prison, though, you get to listening for things more and more.… You get to know a man, and down deep there’s something bothering him bad, and maybe you never find out what it is, but it’s what makes him do like he does, it’s what makes him look like he’s got secrets in his eyes. And you tell him, ‘Calm down, calm down, take it easy now.’ Or you ask him, ‘How come you keep doing the same crazy things over and over again, when you know they’re just going to get you in trouble again?’ Only you know there’s no sense arguing with him, on account of it’s the thing inside that’s making him go. It says, ‘Jump,’ he jumps. It says, ‘Steal,’ he steals. It says, ‘Cry,’ he cries. Unless he dies young, though, or unless he gets everything all his way and nothing big goes wrong, that thing inside of him is going to run down like a wind-up toy. You’re working in the prison laundry next to this man. You’ve known him twenty years. You’re working along, and all of a sudden you hear this click from him. You turn to look at him. He’s stopped working. He’s all calmed down. He looks real dumb. He looks real sweet. You look in his eyes, and the secrets are gone. He can’t even tell you his own name right then. He goes back to work, but he’ll never be the same. That thing that bothered him so will never click on again. It’s dead, it’s dead. And that part of that man’s life where he had to be a certain crazy way, that’s done!”307

The “big click”! What a splendid term for an internal turning point!

In Player Piano, for example, the main character, Paul, ends up in a jail cell next to his rival. He feels an “exotic emotion” that takes him a while to understand:

For the first time in the whole of his orderly life he was sharing profound misfortune with another human being.308

An external turning point, which doubles as a terrific analysis of itself, pops up a few pages later:

Here it was again, the most ancient of roadforks.… The choice of one course or the other.… It was a purely internal matter. Every child older than six knew the fork, and knew what the good guys did here, and what the bad guys did here. The fork was a familiar one in folk tales the world over, and the good guys and the bad guys, whether in chaps, breechclouts, serapes, leopardskins, or banker’s gray pinstripes, all separated here.

Bad guys turned informer. Good guys didn’t.309

And so Paul answers his boss Kroner’s question about who’s the leader of the Ghost Shirt Society.

But I am beginning to explain, which is a violation of a rule I lay down whenever I teach a class in writing: “All you can do is tell what happened. You will get thrown out of this course if you are arrogant enough to imagine that you can tell me why it happened. You do not know. You cannot know.”310

“Show, don’t tell” is an oft-repeated admonition in fiction teaching and writing. The point it makes is important. Fiction strives to provoke a reader into experiencing what is happening, simulating reality, in which no guide deciphers for you the meaning of what is going on. To explain sabotages that fictional realm. In writing class parlance, “show, don’t tell” often implies creating a scene with dialogue rather than narrating a backstory, a character’s observations, and so on. As applied to using scenes, the adage can be overused. All writing methods—narration, summary, and scene—make up a story. The whole point of a plot, though, is that it “shows.” The reader experiences what happens, and what happens makes an impact.

“The thing Kurt seemed to want most in a story,” his student Ronni Sandroff recalls, “was to be surprised. He once challenged us to pause before we turned to the next page in a book and try to guess how the sentence we were in the middle of would end. “You’ll almost always get it right,” he said.

He warned against tiresomeness. He urged originality, freshness.311

In Cat’s Cradle, the chapters are shaped like jokes. Jokes depend on a surprise twist. Those surprise endings keep readers reading as much as the mysteries of plot.

This is the secret of good storytelling: to lie, but to keep the arithmetic sound.312

“I don’t believe it really happened,” Hope objected.

“Makes no difference whether it really did or not,” said the General. “Just as long as it’s logical.”313

For a superb example of “arithmetic,” investigate Vonnegut’s use of the fictional material “ice-nine” in Cat’s Cradle: check out when he first plants it, how he tantalizes us with increasingly surprising information, then its climactic effect on all the characters’ fortunes. You can do the same with the forbidden ritual of “boko-maru.” Or any other science fiction bit you choose.

In Jailbird he employs the true story of Sacco and Vanzetti in exactly the way you’d plot something fictional. He spreads out their tale to keep the reader enticed and entertained, both by the novel and, more importantly, by Sacco and Vanzetti’s history, which he wants so terribly to share.

Sometimes real-life stories such as theirs follow all Vonnegut’s suggestions for keeping your reader entertained.

Even then, when retold, the story’s “arithmetic” must shape something “sound.”

“As for the D. H. Lawrence story, ‘Tickets, Please,’ I am profoundly reluctant to diagram it,” Vonnegut wrote in his thesis, “for it is anything but a simple tale. It is full of horrendous psychological effects, compared to which the plot is nothing. Still and all, let’s see what it looks like on the cross.”314

Hilarious. Yeah, the plot is nothing, he says. Yet let’s see how it works on his diagram—the “cross.”

He worded an assignment he gave at Iowa similarly (see #2 on the “Form of Fiction” assignment dated March 15, 1966, chapter 14).

Kurt was a practical, funny, earnest, ironic man.

Consider this passage from Cat’s Cradle:

There was a quotation from The Books of Bokonon on the page before me. Those words leapt from the page and into my mind, and they were welcomed there.

The words were a paraphrase of the suggestion by Jesus: “Render therefore unto Caesar the things which are Caesar’s.”

Bokonon’s paraphrase was this:

“Pay no attention to Caesar. Caesar doesn’t have the slightest idea what’s really going on.”315

You might say plot is “Caesar.” Plot might not be what’s really going on, but it’s a governing tool, a necessity. It keeps the reader reading. And it may be much more than that, too. What happens, after all, is what happens. And it matters.

Cowboy stories and policeman stories end in shoot-outs… because shoot-outs are the most reliable mechanisms for making such stories end. There is nothing like death to say what is always such an artificial thing to say: “The end.”316

Novices do that also. So many deaths finished off stories in my undergrad Fiction Workshop I classes at Hunter College! Next to beginnings, I have found as an editor, endings need the most touching up and revising. Perhaps because they are artificial, perhaps because exiting is so delicate and can leave such a mark. More than in other parts of a story, attention is drawn to the cadence and the words themselves.

As I approached my fiftieth birthday, I had become more and more enraged and mystified by the idiot decisions made by my countrymen. And then I had come suddenly to pity them, for I understood how innocent and natural it was for them to behave so abominably, and with such abominable results: They were doing their best to live like people invented in story books. This was the reason Americans shot each other so often: It was a convenient literary device for ending short stories and books.317

That’s the horrible part of being in the short-story business… you have to be a real expert on ends. Nothing in real life ends. “Millicent at last understands.” Nobody ever understands.318

The proper ending for any story about people it seems to me, since life is now a polymer in which the Earth is wrapped so tightly, should be that same abbreviation, which I now write large because I feel like it, which is this one:

And it is in order to acknowledge the continuity of this polymer that I begin so many sentences with “And” and “So,” and end so many paragraphs with “… and so on.”

And so on.319