Chapter 36

Love, Marriage, and Baby Carriage

Jane Vonnegut and Maria Pilar Donoso (the writer José Donoso’s wife) were standing on the sidewalk one day having an intense conversation outside where I lived in Iowa City, Black’s Gaslight Village, adjacent to the Vonneguts’. When I came across them, I paused. They explained they were discussing men and marriage. Jane declared, “The thing is, you can’t live with them, and you can’t live without them.”

This encounter jarred my youthful inclination to deem being married a more enviable state than being single. The truth is, each has advantages and disadvantages.

But if you’re going to “live with them,” and you’re a writer or an artist, Vonnegut offers some wisdom and examples.

Advice on choosing a partner serves as the epigraph of Palm Sunday.

Whoever entertains liberal views and chooses a consort that is captured by superstition risks his liberty and his happiness.

It’s taken

from a thin book, Instruction in Morals, published in 1900 and written by my Free Thinker great-grandfather Clemens Vonnegut, then seventy-six years old.566

If you’re a writer or an artist—besides picking someone who’s somewhere in the same ballpark on fundamental issues, as this quote suggests, and all the other considerations in marrying—you need a partner who, at the very least, respects what you do, and at best actively supports it, in whatever ways that may mean to you. Kurt Vonnegut was married twice, to two very different women at two very different times in his life. Both, though in distinct ways, fortified him as a writer.

Kurt and Jane Cox met in kindergarten. As Dan Wakefield notes in his introduction to Vonnegut’s Letters, not only was it a wife’s duty, pre–women’s lib, to be the housekeeper and children’s caretaker, but a writer’s wife was expected to serve as the equivalent of a combination editorial assistant and public relations expert. Jane graduated Phi Beta Kappa from Swarthmore. She thought her husband a genius. She did all she could to support him, except his typing.

If she had not been willing to risk the economic precariousness he took in quitting GE to become a full-time writer, or to take on the primary care of raising not only their three children but their adopted nephews, Kurt’s writing would likely have been derailed. Certainly, he wouldn’t have been able to carve out the protected time she enabled him to have. They built his career together, something he “readily acknowledged.”567

Kurt and Jill Krementz met in 1971 as his and Jane’s marriage was foundering and he was on the crest of fame. They married in 1979. Nearly two decades younger, an ambitious photographer already well known and established in New York, as Kurt’s wife, Jill continued her commitment to her own career, but also arranged and fielded his social commitments and kept the calendar going. Her captivating portraits of him enhanced his book jackets and other publicity. They adopted a child, Lily, and so again, Vonnegut became a parent.

I never knew a writer’s wife who wasn’t beautiful.568

I stayed with Kurt and Jane on Cape Cod in 1969, and I remember Jane pausing, as she swept through the living room gathering up whatever didn’t belong in it on her way out to the garage to drive to Boston to take one of the kids shopping, to tell me her theory of housekeeping. It’s the Swiss-cheese idea, she explained: deal with any “hole” you come across as you come across it.

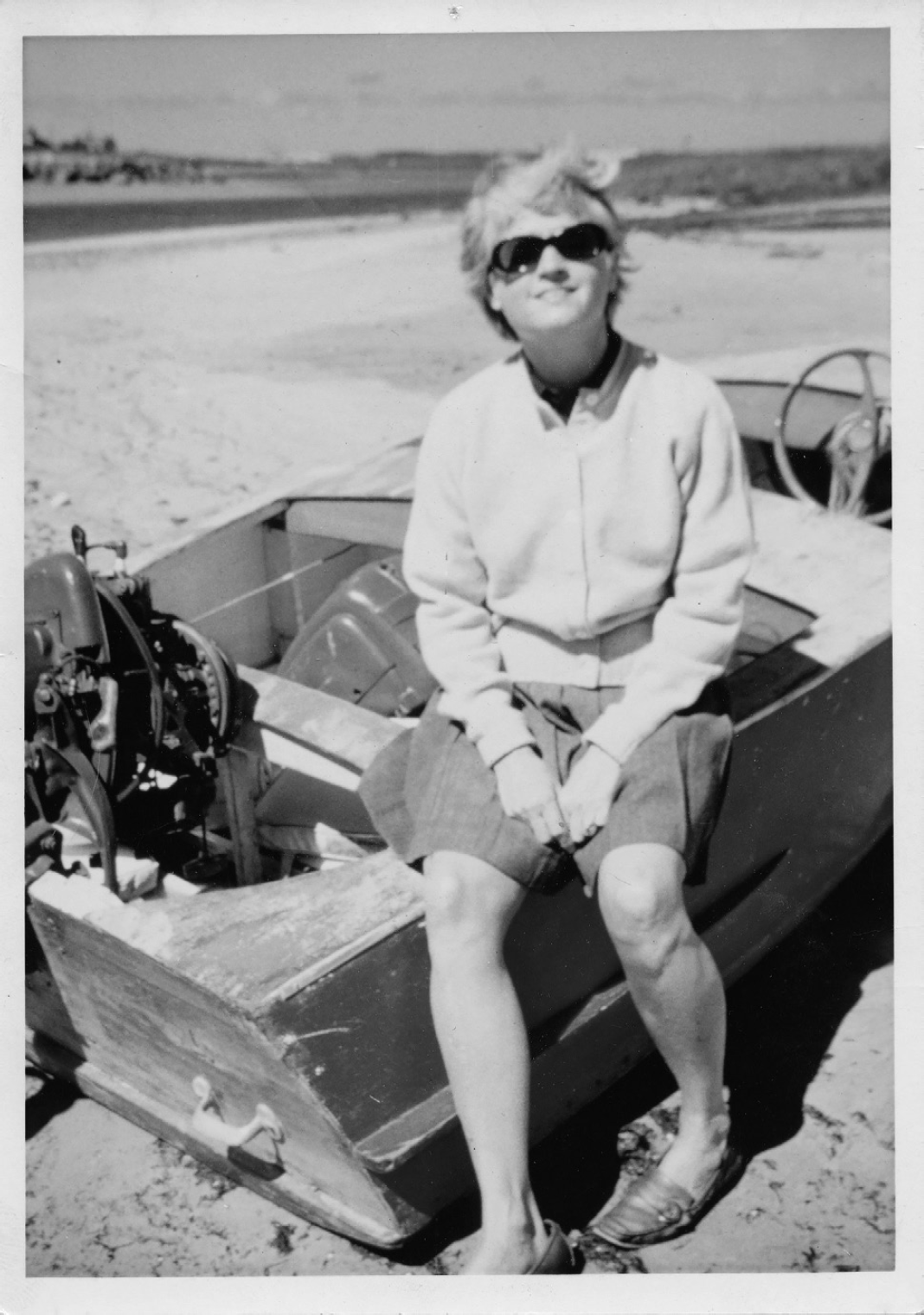

Jane Vonnegut, Barnstable Bay, Massachusetts, 1969. Photo by the author.

One of my own theories about marriage is a roommate idea: a huge part of marriage entails working out the same kinds of things you’d work out with a roommate. Your spouse is your roommate. It’s useful to separate “roommate” problems from other issues. That’s what Kurt’s doing in his contract epistle to Jane (see chapter 1).

My mates have often been angered by how much attention I pay to paper and how little attention I pay to them.

I can only reply that the secret to success in every human endeavor is total concentration. Ask any great athlete.

To be fair to his mates, and honest, he adds:

To put it another way: Sometimes I don’t consider myself very good at life, so I hide in my profession.

But to be fair to himself as a writer, he then adds:

I know what Delilah really did to Samson to make him as weak as a baby. She didn’t have to cut his hair off. All she had to do was break his concentration.569

Kurt Vonnegut had a separate study on Cape Cod and New York in which to write. If you don’t, you can find privacy via public spaces that protect you from domestic interference, such as coffee shops, writers’ rooms, libraries. Even with a room of your own, people can open the door, look over your shoulder, interrupt. But no one is a mind reader. Setting the parameters of your working needs is up to you. Let your mate—your roommate—know what those are. Here’s when consideration for your work is truly put to the test: during the process, in the most mundane everyday way.570

“I have had some experiences with love, or think I have, anyway,” Vonnegut writes in his 1976 introduction to Slapstick,

although the ones I have liked best could easily be described as “common decency.” I treated somebody well for a little while, or maybe even for a tremendously long time, and that person treated me well in turn. Love need not have had anything to do with it.

Also: I cannot distinguish between the love I have for people and the love I have for dogs.

Love is where you find it. I think it is foolish to go looking for it, and I think it can often be poisonous.

I wish that people who are conventionally supposed to love each other would say to each other, when they fight, “Please—a little less love, and a little more common decency.”

My longest experience with common decency, surely, has been with my older brother, my only brother, Bernard, who is an atmospheric scientist in the State University of New York at Albany.

Even in Vonnegut’s unpublished first novel “Basic Training,” he questions assumptions about “love” covering all the complexities of a relationship. The General—who went away to war when his daughter was a baby, so they haven’t had “much time to get to know each other”—says to her,

“You don’t like me because you think I’m a bully, that it’s fun for me to push other people around.”

“Noooo,” objected Hope, tearfully. “I love you, Daddy, really I do.”

“Don’t doubt it. Never did. That’s an entirely different matter.”571

In Bluebeard, his characters discuss what it means to be in love:

“People think we’re in love,” I said to her on a walk one day.

And she said, “They’re right.”

“You know what I mean,” I said.

“What do you think love is anyway?” she said.

“I guess I don’t know,” I said.

“You know the best part—” she said, “walking around like this and feeling good about everything. If you missed the rest of it, I certainly wouldn’t cry for you.”572

Often Vonnegut depicts the roles society has traditionally shaped for men and women, and shows how they affect marriage. They also affect writers.

In Galápagos, just as a guy who’s terrified of dogs is proposing marriage, one comes out barking. The man dashes up a tree. He’s treed for an hour. As a result, he tells the woman:

I am not a man. I am simply not a man. I will of course never bother you again. I will never bother any woman ever again.573

In Hocus Pocus, the narrator, home from the Vietnam War, complains about his wife and mother-in-law:

That mother-daughter team treated me like some sort of boring but necessary electrical appliance like a vacuum cleaner.574

In Player Piano, the wife is trying to stand her ground with two men. One retorts that if she doesn’t show more respect for men’s privacy, he’ll design a machine

that’s everything you are and does show respect.… Stainless steel, covered with sponge rubber, and heated electrically to 98.6 degrees.575

Patty Keene [in Breakfast of Champions] was stupid on purpose, which was the case with most women in Midland City. The women all had big minds… but they did not use them much for this reason: unusual ideas could make enemies, and the women, if they were going to achieve any sort of comfort and safety, needed all the friends they could get.

So, in the interests of survival, they trained themselves to be agreeing machines instead of thinking machines.576

In Cat’s Cradle, the narrator and Mona have just performed the forbidden rite of boko-maru:

“I don’t want you to do it with anybody but me from now on,” I declared.…

“As your husband, I’ll want all your love for myself.”…

She was still on the floor, and I, now with my shoes and socks back on, was standing. I felt very tall, though I’m not very tall; and I felt very strong, though I’m not very strong; and I was a respectful stranger to my own voice. My voice had a metallic authority that was new.

As I went on talking in ball-peen tones, it dawned on me what was happening, what was happening already. I was already starting to rule.577

Marriage has been abolished since the year 23,011 in Galápagos, Vonnegut’s next-to-last novel. The narrator reveals why the institution had been so problematic:

What made marriage so difficult back then was yet again that instigator of so many other sorts of heartbreak: the oversize brain. That cumbersome computer could hold so many contradictory opinions on so many different subjects all at once, and switch from one opinion or subject to another one so quickly, that a discussion between a husband and wife under stress could end up like a fight between blindfolded people wearing roller skates.578

If Mandarax [a translation machine] were still around, it would have had mostly unpleasant things to say about matrimony, such as:

Marriage: a community consisting of a master, a mistress and two slaves, making in all, two.

Ambrose Bierce (1842–?)579

Even blissful coupling can have a downside, Vonnegut shows. The double-agent narrator in Mother Night considers writing a play about that called Das Reich der Zwei—“Nation of Two.”

It was going to be about the love my wife and I had for each other. It was going to show how a pair of lovers in a world gone mad could survive by being loyal only to a nation composed of themselves—a nation of two.…

… Good Lord—as youngsters play their parts in political tragedies with casts of billions, uncritical love is the only real treasure they can look for.

Das Reich der Zwei, the nation of two my Helga and I had… didn’t go much beyond the bounds of our great double bed.…

Oh, how we clung, my Helga and I—how mindlessly we clung!

We didn’t listen to each other’s words. We heard only the melodies in our voices.580

Buried in each other’s arms, they avoid responding to the world or even to the fuller reality of each other.

Here’s Vonnegut’s wisdom on divorce, straight from the horse’s mouth:

I’m to love my neighbor? How can I do that when I’m not even speaking to my wife and kids today? My wife [Jill] said to me the other day, after a knock-down-drag-out fight about interior decoration, “I don’t love you anymore.” And I said to her, “So what else is new?” She really didn’t love me then, which was perfectly normal. She will love me some other time—I think, I hope. It’s possible.

If she had wanted to terminate the marriage, to carry it past the point of no return, she would have had to say, “I don’t respect you anymore.” Now—that would be terminal.

One of the many unnecessary American catastrophes going on right now… is all the people who are getting divorced because they don’t love each other anymore. That is like trading in a car when the ashtrays are full. When you don’t respect your mate anymore—that’s when the transmission is shot and there’s a crack in the engine block.…

“Ye shall respect one another.” Now there is something almost anybody in reasonable mental health can do day after day, year in and year out, come one, come all, to everyone’s clear benefit.581

But although they divorced, he and Jane never lost respect for each other.

Several weeks after giving birth for the first time at the age of thirty-nine, my stepdaughter remarked in her wonderfully understated way, “It gives a whole new meaning to full-time job.”

In Bluebeard, the characters discuss art and family life.

“I always wanted to be an artist,” I said.

“You never told me that,” she said.

“I didn’t think it was possible,” I said. “Now I do.”

“Too late—and much too risky for a family man. Wake up!” she said. “Why can’t you just be happy with a nice family? Everybody else is.”582

In Palm Sunday, Vonnegut says:

I would actually like to have "The Class of ’57" [a country hit about ordinary people’s dreams and lives] become our national anthem for a little while. Many people have said that we [my generation] already have an anthem, which is my friend Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl”.… I like “Howl” a lot. Who wouldn’t? It just doesn’t have much to do with me or what happened to my friends.…

Also, and again I intend no offense, the most meaningful and often harrowing adventures which I and many like me have experienced have had to do with the rearing of children. “Howl” does not deal with such adventures.583

“Meaningful” and “harrowing.” Parenting is life changing. It’s as demanding as anything can possibly be. Artists and writers are often notoriously poor parents. If you decide to parent, do so with your eyes wide open. Parenting, too, is an art.

“My mother and father,” Mark Vonnegut wrote, “at the ripe old age of thirty-five, struggling financially (ten years prior to Slaughterhouse-Five), took on four more children, two dogs, and a rabbit. Whatever else good or bad my parents did or didn’t do with the rest of their lives, that was absolutely the right thing to do.”584

As Vonnegut says, through his character Constant in The Sirens of Titan,

A purpose of human life… is to love whoever is around to be loved.585

Doing the right thing can cost you.

A stew of factors led to the demise of Kurt and Jane’s twenty-five-year-plus marriage. One, though, may have been the strain of loving, in practice, so many children over so many years.

What kind of a father was Kurt Vonnegut? A 1982 reminiscence from his eldest daughter, Edie, offers a glimpse:

When I was sixteen and taking a lot of liberties, I decided to start calling my father “Junior.” Just “Junior.” “Uh, may I please have a ride to Hyannis, Junior?” I never got punished for this transgression; in fact, it was never even remarked on. He simply responded to the name as though nothing were different. I don’t think he exactly thrilled to this new familiarity. It was not an appropriate name for a father, especially such a tall father. Junior had a diminutive ring to it. He never objected to it, though. I thought it was funny and meant it affectionately. It made him my size somehow. I think the reason I felt free to reduce him like this was because of something that happened when I was twelve. I remember being all confused about life and God and all, and I asked him what was going on, thinking he’d know, being older and a father, and what he said was my first big revelation. He said that in the grand scheme of things we were scarcely older than each other. From our point of view there seemed to be a colossal difference, but in the bigger picture he was perhaps half a second ahead of me, if that… and that we were both experiencing the same things at the same time for the first time. Like our dog dying was a first for both of us. That he had no more of a handle on things than I did. This was really news to me. I thought it was just a matter of time before he let me in on what he knew. Ever since then I’ve seen him as a sort of peer and buddy, and a plain ordinary person trying to sort things out in the dark, just like me. I appreciate that, and admire that he didn’t play the wise role. It’s made me consider him a human being before a father. It also let me know full blast at a very early age that I was on my own as far as figuring things out went. I consider this all the Truth and am grateful for it.… Hence, Junior.… Since then he has formally dropped the Junior from his name, with a lot of philosophy behind it. I wonder if he wasn’t just plain sick of his daughter calling him Junior all the time. I don’t call him Junior anymore. I call him Dad. Though inside I’m mightily tempted to call him Junior, or Scooter or Butch or something very fond and funny and familiar. Maybe Fuzzy or Ducky.586