Introduction

Here we go again with real life and opinions made to look like one big, preposterous animal not unlike an invention by Dr. Seuss, the great writer and illustrator of children’s books, like an oobleck or a grinch or a lorax, or like a sneech perhaps.

—kurt vonnegut, Fates Worse than Death

I was a student of Kurt Vonnegut Jr.’s at the University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop in the late ’60s, and we remained friends from those years until his death. I gained a great deal of wisdom from him as a writer, as a teacher, and as a human being. This book is intended to be the story of Vonnegut’s advice for all writers, teachers, readers, and everyone else.

Vonnegut was not famous when he started teaching at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. He’d published four novels. He was working on Slaughterhouse-Five. He was forty-two years old.

The first time I saw him (and I didn’t know who he was), he struck my funny bone. He stood in front of a lecture hall with the other writers who were to be our teachers. He was tall, with curving shoulders (a man shaped like a banana, as he once described himself), and he was smoking a cigarette in a long black cigarette holder, tilting his head and exhaling smoke, with a clear awareness of the absurdity and affectedness of it: in other words, he had—as Oscar Wilde said is the first duty in life—assumed a pose.

He was, I learned later, seriously trying to reduce the effects of smoking by using the cigarette holder.

The Iowa MFA was a two-year program, long enough so that students eventually gravitated, as if by osmosis, to teachers with whom they had an affinity. I found my way to Vonnegut’s workshop classes by my second year.

Meanwhile I read Cat’s Cradle and Mother Night, the two books he’d most recently published. So I became acquainted with him as a writer through those novels at the same time as I was getting to know him as a teacher and a person.

I lived next door to the Vonnegut family my first year, in a place inhabited by grad students called Black’s Gaslight Village. Our geography continued to be adjacent. I visited Kurt in Barnstable, saw him in Michigan when I first taught and he lectured there, moved to New York City about the same time he did, and for the last thirty-five years have spent summers an hour from where he lived for two decades on Cape Cod. Kurt and I had lunch occasionally, wrote letters, spoke on the phone, ran into each other at events. He sent a lovely blown-glass vase as a wedding present. We never lost touch.

You probably met Vonnegut also through reading his books, assigned in high school or college or read independently, depending on your age. If you read Slaughterhouse-Five, the most well known, you also know the experience that drove him to write that book because he introduces it in the opening chapter: as a twenty-year-old American of German ancestry in World War II, he was captured by the Germans and taken to Dresden, which was then firebombed by the British and Americans. He and his fellow prisoners, taken to an underground slaughterhouse, survived. Not many other people, animals, or vegetation did.

That event, and others, fueled his writing and shaped his views. (It did not, however, as is often assumed, initiate it. He was already headed in the direction of being a writer when he enlisted.) I intend to guide you through the maze of his advice like a director-puppeteer, relating experiences from his life when they shed light on how he obtained the wisdom he imparts; specifying, insofar as possible, from what point in his life a piece of advice derived—as a beginner, mid-career, or a mature writer; and telling anecdotes about him and from my own life, when relevant.

I was asked to write this book at the behest of the Vonnegut Trust. Dan Wakefield was supposed to do it. But exhausted from compiling two other marvelous books of Vonnegut work, Letters, an annotated selection of letters, and If This Isn’t Nice, What Is?, an anthology of speeches, and yearning to return to his own fiction, he phoned me. “You’re the perfect person to do this book,” he said, persuasively. “You’ve been a teacher of writing, you’re a fiction writer yourself, you were his student, and you knew him. It’s a great fit.”

About 60 percent of it had to be the words of Kurt Vonnegut. Otherwise, how it was composed would be entirely up to me.

All I had to do, Dan said, was write an introductory proposal, and send it and the profiles I had published on Vonnegut in the Brooklyn Rail and Writer’s Digest, as evidence of my capability and writing style, to the head of the Vonnegut Trust, Vonnegut’s friend and lawyer Don Farber, and the e-book publisher Arthur Klebanoff, head of RosettaBooks. Dan Wakefield had already told them about me.

A month later, while volunteering at the Kurt Vonnegut Museum and Library table at the Brooklyn Book Fair, the library’s director, Julia Whitehead, introduced me to Dan Simon, the founder of Seven Stories Press, who had published the final two books by Vonnegut, and knew him well. I explained this project. Simon murmured, “I’d love to publish that book.” The result was a new contract between the Vonnegut Trust, RosettaBooks, Seven Stories Press, and myself. Voilà. Whatever form you’re reading this in, we’ve got you covered.

Wilfred Sheed said of Vonnegut, “He won’t be trussed up by an ism, even a good one.” He preferred to “play his politics, and even his pacifism, by ear.”1 Vonnegut was prone to seeing the other side of the coin, ambiguity, and contradiction.

He had, after all, been captured, imprisoned, and forced into labor carting corpses by an enemy regime rotten with idolatry, decayed by a people’s desire for easy, authoritarian solutions.

He would appreciate this palindrome by Swiss artist André Thomkins: “dogma i am god.”

For my part, I want to avert, as much as possible, my own and the reader’s impulse to make dogma out of Kurt Vonnegut’s advice. One way I hope to accomplish that is by adopting the concept of “endarkenment.”

It’s borrowed from Profound Simplicity by Will Schutz, published in 1979, “the one book that gives meaning to the Human Potential Movement,” according to the cover. Schutz, a leading psychiatrist in that movement, lists his credentials early on: he’d explored every mind-, body-, and soul-expanding avenue the movement had yielded up. He’d also led innumerable seminars at Esalon Institute. It’s a concise, down-to-earth, truly helpful book (presently out of print). But the part that has stuck with me for forty years is his final chapter, “Endarkenment.” It begins, “Sometimes my striving toward growth becomes the object of amusement to the part of me that is watching me.” He tired, occasionally, of that striving and rebelled.

So he devised a workshop called “Endarkenment.” In it the participants were encouraged to be devious, superficial, and to wallow in their self-made misery. They drank hard, smoked like chimneys, stuffed themselves with junk food, and blamed everybody else for their problems, starting with the other workshop members all the way up to Almighty God. In teaching sessions, each person divulged their worst trait and explained how the others could acquire it. One man said he never finished things. He promised he’d teach the group how to do that the following Wednesday. When Wednesday came, he had dropped out of the workshop.

The results of the Endarkenment workshops were startling. They were as effective as regular workshops in raising people’s awareness of the human comedy, and in realizing that they themselves chose what they did and that therefore they could make other choices.

I’ve adapted the word “endarkenment” and redefined it to use as a guiding principle. When alternatives, ironies, warnings about, or contradictions to previous advice or ideas pop up, the concept of endarkenment is at work. (Originally the word in bold marked those places, but these intrusions bit the dust in the editing process). This term and methodology, I hope, will trigger the notions that truth (not the same as facts) can be many sided, and that Vonnegut was a human being, not a dogma god.2

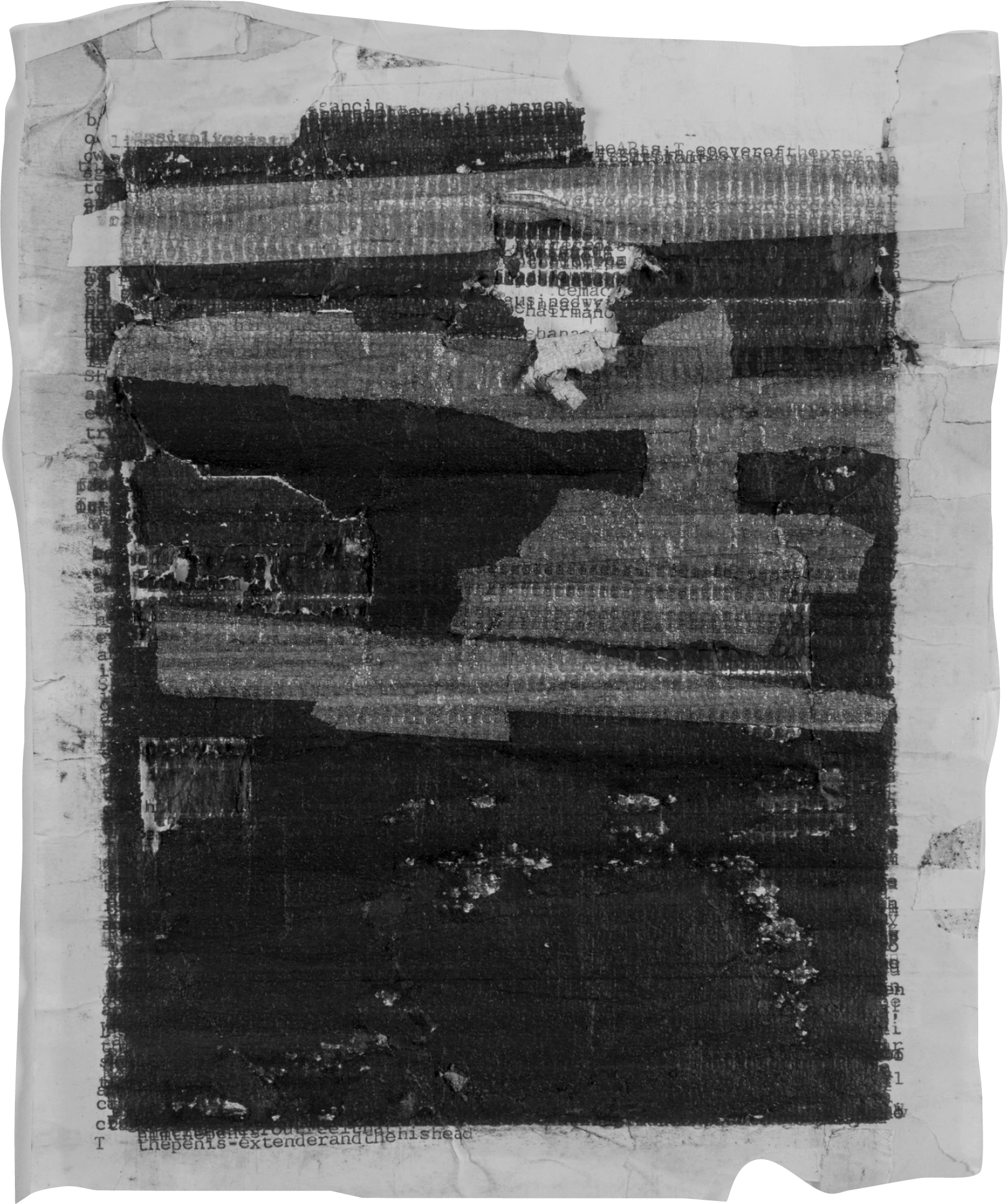

Right after I was offered this project, Julia Whitehead turned me on to artist Tim Youd, who had just been doing a performance at the Kurt Vonnegut Museum and Library. His art? Retyping novels, using the typewriter model that the writer used, in the same place where the writer worked or the novel takes place. He types the entire novel using the same page over and over, with a cushioning sheet beneath, reading aloud, “sort of in a mumble,” to keep his place and stay engaged. The page rips. He applies masking tape and continues. The accidental punctures and tears create the tangible work of art: at the end, he separates the top and bottom sheets and frames each.

At the Kurt Vonnegut Museum and Library, Tim Youd typed Breakfast of Champions one week and Slapstick the second, using an electric Smith Corona Coronamatic 2200.

Tim Youd, Kurt Vonnegut’s Breakfast of Champions, 2013, typewriter ink on paper. 303 pages typed on a Smith Corona Coronamatic 2200, Kurt Vonnegut Museum and Library, Indianapolis, Indiana, September 2013.

“The experience of immersing myself for two solid weeks gave me an appreciation of Vonnegut’s genius. And especially of his bleakness,” Youd said.

One of Youd’s purposes is to focus people’s attention on the writer’s work. “We’ve come to the point where we’re more interested in looking at the scrolls of Kerouac than reading Kerouac. The same with Hemingway’s home in Key West.” Fetishism of famous writers, he suggested, occurs because “it’s such heavy-lifting to actually read books.”

Swag proliferates around Vonnegut: mugs, greeting cards, bookmarks, note cards, mouse pads, T-shirts. Indianapolis sports a mural of him on a downtown wall. His phrases name coffee shops, bars, bands. People tattoo his quotes on themselves.

Whether these artifacts honor or defile, act as talisman or kitsch, only God and the individual can know.

Tim Youd acknowledges that his own performances may contribute to fetishism. I fear contributing as well. Because I’ve taken Vonnegut’s marvelous words out of context. I’ve shifted, shortened, somersaulted, and squished them into molds for the purposes of this book.

It’s like the quotes of Vonnegut’s that appear frequently online. They’re out of context, like anyone’s quotes, and sometimes misleading. For example, his rules for writing the short story, listed in the short story collection Bagombo Snuff Box, aren’t intended to apply to the novel. But they pop up as rules for writing all fiction.

A person could read Pity the Reader without ever reading Vonnegut’s fiction. But his words within these pages belong first in their proper homes, where they were born.

When Dan Wakefield published his first best-selling novel in the ’50s, his publisher, who was also Vonnegut’s, asked Vonnegut if he would be Wakefield’s editor. That editorial work, Dan says, “consisted of a two-page letter to me with seven suggestions for improving my novel. I carried out four of the seven, and my novel was better for it. Most important of all was his advice that I should not follow any of his suggestions ‘just because I suggested them.’ He emphasized that I should only carry out those suggestions ‘that ring a bell with you.’ He said I should not write or change anything simply because he (or any other editor or writer) suggested it unless the suggestions fit my own intention and vision for the book.” Wakefield says it was “one of the most valuable editorial lessons I ever learned.”

Looking back at Vonnegut’s assignments at the Writers’ Workshop now, I see that more importantly than the craft of writing, they were designed to teach us to do our own thinking, to find out who we were, what we loved, abhorred, what set off our trip wires, what tripped up our hearts.

It’s my ambition that Vonnegut’s words in this book will provoke similar effects for readers.

Kurt Vonnegut said:

When I write, I feel like an armless, legless man with a crayon in his mouth.3

Is this advice? It is for me. It says: You can do it. Every writer feels inept. Even Kurt Vonnegut. Just stick to your chair and keep on typing.

What’s more, though, and uniquely Vonnegut-esque, is that it’s outrageously comic and demands perspective. Because I’m fortunate. I’m not armless or legless, and I have more than a crayon. Don’t most of you?

And so it goes as good advice for teachers who despair of teaching, for readers who don’t understand a difficult text, for anybody tackling anything and feeling inadequate to the task. That just about takes in all of us. Carry on! Cheer up! Have a good laugh! We’re all inadequate to our tasks!

Vonnegut was fueled as a writer by humanitarian issues he wanted to bring to the attention of others. Those of us who were his students were fortunate. But his readers are his largest, most important student body.

As a teacher at the Writers’ Workshop, Vonnegut was passionate, indignant. He wheezed with laughter. He was considerate, sharp, witty, entertaining, and smart. In other words, he was similar to the author of his books. Though not without protective poses, he was very much himself—the same funny, earnest, truth-seeking, plainspoken Hoosier—whenever he spoke and in whatever he wrote.

Kurt Vonnegut was always teaching. He was always learning and passing on what he learned.

I have assigned Vonnegut’s stories, novels, and essays to a wide spectrum of students. His work crosses borders of age, ethnicity, and time. Two of the best assignments and liveliest, most effective classes I’ve ever taught were inspired by Cat’s Cradle—one in an Introduction to Literature class in the late ’60s at Delta Community College, and the other in a Literature of the ’60s class shortly after September 11 in 2001 at Hunter College—thirty years apart.

What I hope we will be doing here, to quote Vonnegut on the pleasure of reading stories, is “eavesdropping on a fascinating conversation” that he was having with his readers.

I am reminded of the way one begins a letter to an anonymous but responsible and hopefully responsive person: “To Whom It May Concern.” This phrase may sound formal and removed to some, since that’s how it’s usually used. But please take it literally and as it’s meant here, as a warm welcome: to all whom it may concern.