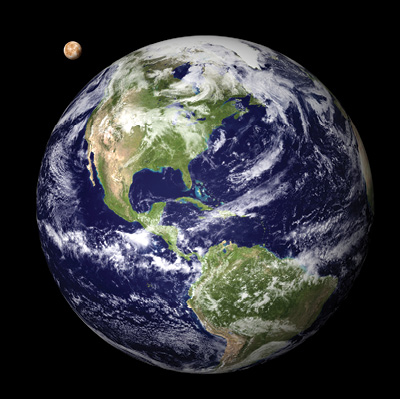

Funny how we call such a watery planet Earth! CORNELIUS20/DREAMSTIME.COM

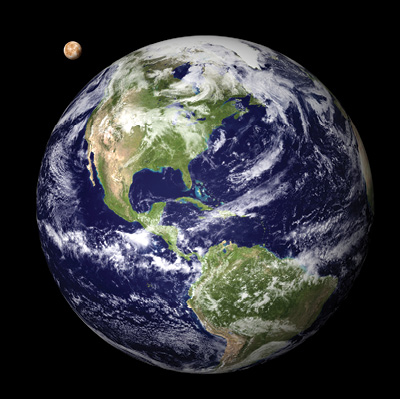

Funny how we call such a watery planet Earth! CORNELIUS20/DREAMSTIME.COM

Ever wonder why we call our planet “Earth” when most of it is covered in water? It’s kind of funny when you think about it.

Not to brag, but we’ve got more water than any other planet in our solar system, and water means life. All living things need water. It dissolves minerals and nutrients from our food and carries them around our bodies. When you water a plant, the water dissolves minerals in the soil. The plant’s roots draw up that mineral-rich water. Then the leaves blend the water, minerals and air with energy from the sun to make nutrients. These nutrients feed the plant. When you eat plants, your blood (which is mostly water) transports the plants’ nutrients throughout your body.

But our watery planet with the funny name doesn’t have a limitless supply of drinking water. In fact, 97 percent of Earth’s water is in our oceans—blech! Salt water! Totally undrinkable!—and most of what’s left is trapped in glaciers and ice caps. Of all the water on the planet, only 1 percent is fresh water that plants and animals, like us, can drink. If it weren’t for the fresh water of rivers, lakes and streams, we wouldn’t have a drop to drink!

Around the world, most glaciers are melting at an astounding rate. GASTÓN CASTAÑO

WATER FACT: Imagine all the water of the world in a four-liter (one-gallon) bucket. Only a tablespoonful would be drinkable fresh water.

Did you know that you’ve probably drunk some of the same water that a dinosaur sipped from a puddle a few million years ago? We’ve had the same amount of water on the planet for two billion years. It’s constantly recycled in a big natural system called the water cycle.

How does the water cycle work? The sun heats Earth’s water, and when water gets hot, it turns to vapor. Up it floats into the air, and then—bam!—it hits colder air and condenses into clouds. When the clouds get heavy with all that water, the water falls back to Earth, either as rain or snow. Some of that rain goes right back into oceans, lakes and streams. Some sinks into the soil, and some seeps so far down into the ground that it collects as an aquifer or underground lake. (Aquifers take thousands of years to form, and aquifer water can remain underground for hundreds of years.) Some of the water that falls as snow becomes part of the world’s glaciers or polar ice. The cycle repeats constantly and has done so for billions of years.

Monsoon season in Thailand has always meant a lot of rain. In 2011, monsoons caused dangerous flooding. THOR JORGEN UDVANG/DREAMSTIME.COM

In 1978, Iguazú Falls in Argentina dried up for 28 days. Imagine all this water evaporating, leaving only dry soil. GASTÓN CASTAÑO

But recently, with global warming, climates around the world have begun to change. The polar ice is melting and flowing into the ocean. Some parts of the planet are receiving more rain than ever before; people are flooded out of their homes, and water reservoirs might be filled with dirty runoff. In other places, rain hardly falls at all anymore, and lakes, streams and even rivers are drying up. Water sources that people have relied on for thousands of years are changing.

Wetlands like this one inspired the first water treatment plants. BRONWYN8/DREAMSTIME.COM

Turn on a tap. Fill up a glass with water. Admire this liquid that’s been around for billions of years. Animals have bathed in it. It’s been through the mud. Maybe it’s even sloshed around a toilet bowl at some point. And we drink that stuff!?

Before you vow never to drink another drop again, remember that people existed in the world for thousands of years before anyone invented water filters. That’s because nature has its own filtration system. It’s called a wetland.

A wetland is a marsh or swamp or any area of land where the soil near the surface is covered with water. The soil in these places acts like a pollution filter. Contaminants that pollute the water attach to sand or organic material. Bacteria break down nutrients and feed them back into the ecosystem. Wetlands can be overwhelmed though. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, people created so much pollution with farming and other industries that the wetlands couldn’t handle it. The swamps were swamped!

These bottles of water on the side of a road in Argentina are gifts to an unofficial popular saint, la Difunta Correa, who died of thirst in the desert. MICHELLE MULDER

I saw shrines like this one all over Argentina when I traveled there with my husband. Legend has it that over 150 years ago, a woman crossing the desert with her baby died of thirst on the way. But her baby survived “miraculously” by nursing for days after the mother had died. The woman has become a local saint, and people throughout Argentina, Chile and Uruguay ask la Difunta Correa to help them reach their goals. In thanks, they leave a bottle of water at one of the roadside shrines.

If given a choice, most people wouldn’t drink this water, but even water that looks clean can be dangerous. Parasites and chemical pollution are often invisible and deadly. CAWST (CENTRE FOR AFFORDABLE WATER & SANITATION TECHNOLOGY)

What are your options if you don’t have a water treatment plant nearby? These kids in El Salvador rely on a biosand filter, which cleans water the same way a natural wetland does. More about that in Chapter Three. CAWST

So people began looking for ways to clean the pollution out of their water before drinking it. In 1804, the town of Paisley in Scotland built the world’s first citywide municipal water treatment plant. The plant used a sand filter system to clean the water before pumping it to people’s homes. In other words, Paisley built a water-cleaning factory that worked just like a wetland. Now, many cities and towns around the world have systems for cleaning the water before it reaches people’s homes.

But we keep dumping more waste into the water. Each day people dump 1.8 billion kilograms (2 million tons) of waste into waterways. Toxic chemicals from landfills, factories and mining, as well as garbage, sewage and acid rain, all pollute our water. Meanwhile, since the year 1900, we’ve drained, paved over, or otherwise destroyed half of the world’s wetlands. Clean water is getting harder and harder to find.

Water treatment can be as simple as a sand filter, or as complex as this water treatment facility. NOSTAL6IE/DREAMSTIME.COM

The clean, fresh water that comes out of your tap may have had a long, complicated journey to your house. Chances are, it began in a reservoir—a big, human-made lake used to collect water. From there, the water likely drained through a mixture of sand and gravel to filter out dirt (in a water treatment plant—another one of those human-made wetlands). Next, chemicals like chlorine might have been poured in to kill any remaining germs. Only then does the water pour into big pipes that lead to your town or city. The pipes, called mains, run under streets and then through smaller pipes to buildings. Finally, even smaller pipes lead to your sink, toilet and bathtub.

Ever wondered what goes on underground? The Paris Sewer Museum (Le Musée des Égouts de Paris) offers visitors a chance to explore a sewer system that dates right back to 1370. (Nose plugs not included.) RAPHAËL GALICHER

Water that goes down drains or toilets flows out of the building to an underground sewer main. From there, it likely flows to a wastewater treatment plant. Screens filter out large solids, and depending on where you live, the poop is dumped into a sewage landfill or burned for energy. Gravity and finer filters remove smaller solids before the liquid pours into basins where bacteria eat up any remaining organic matter. (That’s the polite way of saying “little bits of poop that escaped all those filters.”) Sometimes chemicals or ultraviolet light might give the water its final “scrub” before it flows back out into the world’s rivers, lakes and oceans. Wastewater plants help keep the world’s water clean. Many places choose not to build them though, because they’re so expensive.

And at this point, maybe you’re wondering why we poop into water in the first place. Wouldn’t it be easier to keep the world’s water clean if we didn’t? More about alternatives in Chapter Four.

WATER FACT: Water can carry disease, but with a bit of soap, it also gives us one of the easiest ways to prevent illness.

Around the world, people are resisting Canadian mining companies whose mining techniques could poison local drinking water. This graffiti says “No to the mine.” MICHELLE MULDER

For a long time, when I traveled, I proudly wore a Canadian flag pin on my jacket. But in Esquel, Argentina, people glared at me, and I soon learned that a Canadian mining company was exploring the area to develop a gold mine. Across the city, citizens were holding meetings about the arsenic used in this exploration and discussing how that poison might filter into the drinking water. Horrified at the idea of being mistaken for a water-poisoner, I took off my Canadian pin, and people started smiling at me in the streets again.

Engineers hope to tow large icebergs to the dry country of Saudi Arabia as a new source of fresh drinking water. (Meanwhile, other countries already tow fresh water across the sea in a different form. Ships from the Greek mainland drag enormous bags of fresh water to the Greek islands.) MICHELLE MULDER

Around the world, people are talking about a water crisis. As both human population and industry grow, we need more and more fresh water. But climate change means water supplies are harder to predict. Technology that allows us to pump water out of aquifers means that many of them are emptying completely. (They’ll take thousands of years to fill up again.) And harmful chemicals from mining and other industries, as well as sewage, are polluting more and more of our drinking water supply. Less and less of Earth’s water is clean and available to drink.

That’s why people around the world have thought up clever ways to get—and clean—that all-important liquid. And kids play a big role in that process. In many cultures, kids are the ones who gather the water for their families. In other places, like North America, kids often teach adults how to protect our water for future generations.

WATER FACT: Forty-three percent of the world’s population—that’s almost three billion people—do not have water taps in their houses or even nearby.

Ganges River, in India and Bangladesh, is one of the world’s most polluted rivers. Yet millions of people depend on its water for their daily needs. These Hindu pilgrims are bathing in the river as part of a religious festival. NEELSKY/SHUTTERSTOCK.COM