The art of perfumery developed from humankind’s original attempts to enhance reality through scent. Incense was probably the first means of controlled scent delivery and distribution. The word perfume actually means “through” (per) “smoke” (fume). Over thousands of years, perfumers’ lore has passed down via oral tradition to a select few. Secrets of professional perfumery were closely guarded. Perfumers felt privileged to work with the pure essences of nature and considered their raw materials energizing and protective. It was believed in the Middle Ages that perfumers were exempt from the Plague.

An aura of mystery still permeates the world of perfume. Successful formulas are considered top secret, and perfumers jealously guard recipes and sources. Respect for the natural ingredients, however, has not remained preeminent. Sadly, most modern perfumers are trained to use synthetics, chemicals, and compounds so toxic to the nervous system that many fall ill.

The classical concept of placing aromatic oils onto a three-note scale provides a structure upon which to build balanced and pleasing blends. Creating a perfume is not unlike composing a piece of music. The arrangement of a perfume resembles a three-part fugue. The part of the perfume known as the top note touches the sensibility first and vanishes in a few moments. Then the middle note, or heart, sets the theme, which can last for hours. Finally the bass note, or dry-out note, provides depth. The resonating chord of the bass note might linger for days.

Certain oils can be used as more than one note. For example, orrisroot is a great fixative or bass note, but is also often used in the heart, or middle, for its soft violet scent. Angelica’s rooty, animal scent makes it an effective bass note as well, while its green, acidic quality makes a good top note.

“You have to be crazy in a way,” said the famous New York perfumer Sophia Grojsman about creating perfumes. “When I compose I go right to the heart of a fragrance. Some people smell top notes first. I go deeper, I search for the soul. I build my fragrance from the bottom to the top, like a pyramid, in layers. It’s geometric. The art closest to what I do is music. . . . Compare your perfumes to an opera.”

“You dream your perfume before you write the formula,” said Jean Kerleo, a perfumer for Patou, in describing the creative process. “You begin as a composer and finish as a sculptor.”

Note: Top

Acts upon: Spirit

Plant part: Flowers, spices

Note: Middle

Acts upon: Emotion

Plant part: Leaves, flowers

Note: Bass

Acts upon: Physical body

Plant part: Resins, wood, bark, roots

Bass notes act as the foundation to a blend. Earthy, woodsy smells, they are often deep and mysterious, seductive and haunting. Bass notes are grounding to the spirit. A bass note might evoke a walk in the forest, the scent of damp humus, or an old dusty wine cellar. Without a bass note, a perfume will not last.

Some effective bass notes are:

Middle notes are also called bouquet or heart notes. The middle note is the scent that unfolds a few moments after the application of a perfume. Herby and flowery, the middle note is like the entrée to a meal, or the stuffing in a sandwich. The middle note also has the task of weaving together the top and the bottom — just as in music, a number of separate strings or notes together create a chord.

Some effective middle notes are:

The top note is the peak, the fragrance prelude that affects the olfactory sense as a first impression. Effective top notes are delicate, light, and fresh, and are usually sweet, fruity, or spicy. They brighten up your senses and spark your attention. They are also ephemeral, leaving very quickly so you don’t get too attached.

Some effective top notes are:

This is really a lot of fun as well as serious work. Reserve a quiet time to work on scent evaluations. Prepare everything you will need ahead of time. Collect at least 20 or 30 different essential oils, some from each group of top, middle, and bass notes. Make perfume blotters by cutting pieces of paper into strips 1⁄8 inch (3 mm) wide and 6 inches (15 cm) long. Watercolor paper found in art stores works well.

Make yourself comfortable in a big soft chair with a table or desk at hand. Light a candle for inspiration. Select an oil to evaluate and write the name of the oil on one end of a paper blotter. On the other end place a drop of the oil and waft the scent by waving the blotter a few inches under your nose. Sniff lightly (avoid deep inhalations), and record your impressions on an index card. Be creative. Describe your feelings and thoughts. Imagine the scent as a color or a shape and describe it. Give it a texture. Use adjectives. You can refer to the Vocabulary of Scents for ideas.

These scent evaluation cards will become a valuable resource. Keep them for reference when you begin building perfume blends.

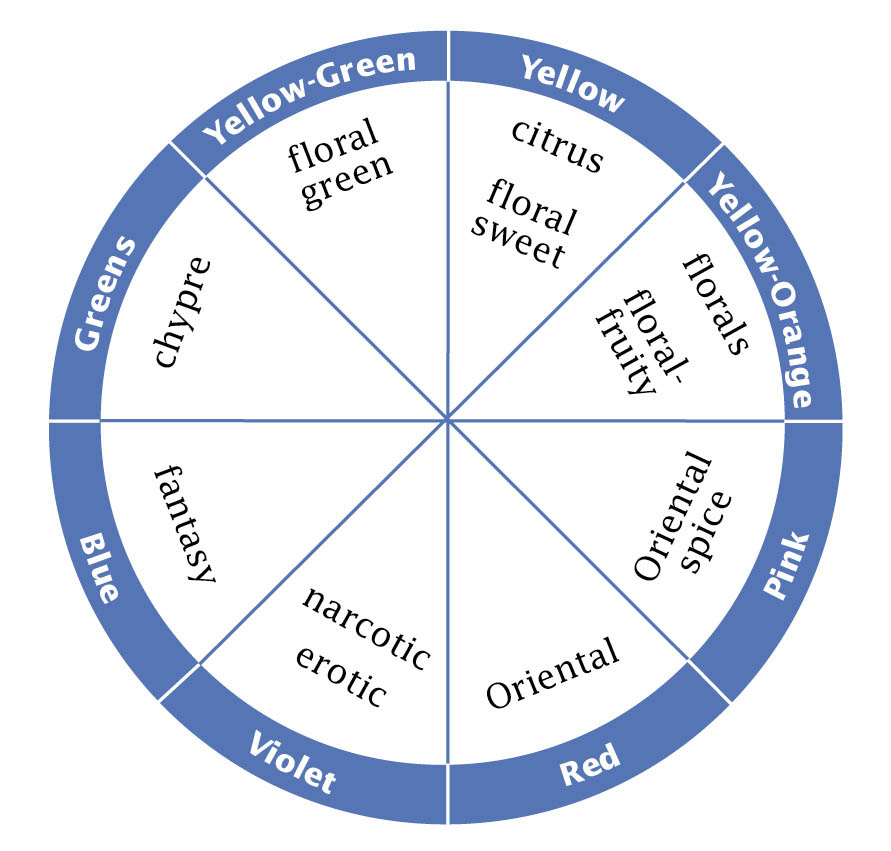

You may find it helpful in this process to picture an abstract perfumery color wheel. A part of the universal language of perfumery, the color wheel performs as a visual expression of scent. Imagine that the yellow-orange colors are the florals. See the hot pinks of the Oriental spices. Picture the green of the chypres, the cool mossy green of oakmoss, and the bright green of lime and bergamot.

As you develop a perfume blend, it might help to think of scents in terms of corresponding colors, as indicated on this perfumery color wheel. You can select scent combinations just as you would flower colors for a perfect bouquet.

The International fragrance market is huge. There are more than 700 products available, including everything from feminine perfumes to classic perfumes. The H & R Genealogies is an attempt to order and categorize the perfumes on the world market similar to the classifications of styles or schools of art, such as impressionist, cubist, German expressionist, Fauvist, and so on.

Perfume styles are based on families, which in turn are subdivided into fragrance characteristics. These classifications were developed primarily from the viewpoint of the consumer. In natural perfumery, every perfume can be assessed on the basis of these fragrance styles.

Florals. Florals are by far the most popular scents. More than half of the world’s perfumes fall into this category. Floral can manifest as springlike, fresh, and light; as fruity, green, and balsamic; or in heavy floral themes.

The many branches of floral include floral green, floral fruity, floral fresh, floral floral, floral sweet, and floral aldehydic (a purely synthetic group).

Oriental. Most popular in Europe and the United States (as opposed to Asia), these woody and floral blends contain spicy ingredients like nutmeg and cinnamon. The two branches are Oriental sweet and Oriental spicy.

Chypre. Named after the island of Cyprus, all chypres (pronounced Shee-praz) share a common theme in their bass of oakmoss, patchouli, and amber, combined with a fresh citrusy top note, usually featuring bergamot. Branches are chypre floral, chypre fresh, chypre green, chypre fruity, and chypre floral-animalic.

Fantasy. A new category of perfumes, fantasies are mostly synthetic and make no attempt to mimic the natural smells of flowers or plants. Fantasy perfumes represent an image or concept, such as “cool water” or “blue lagoon.”

Feminine fragrance styles

Masculine fragrance styles

Just as in art, music, or cooking, we can foster a familiarity with our medium by studying the work of great masters. We can learn by studying the balance and complexities of world-famous perfumes.

When using recipes and formulas, you have exact proportions or drops to follow. But experimenting with variations on classic scent themes will help you develop artistry in your blending. The following list of formulas comprises classic perfumes, along with some of my personal favorites. Since these are commercial formulas, exact combinations cannot be disclosed, but very strong oils that must be used sparingly are noted with an asterisk.

One of the best ways to train your nose to be sensitive to the subtleties of scent is to study the classic perfumes and try to identify the elements hidden within.

Some oils are especially difficult to find; you can make substitutions, though.

Ylang ylang can be used in place of many sweet florals, such as hyacinth and orchid.

Middle green notes can be achieved with combinations of galbanum, bergamot, green aniseed, and petitgrain. Store this blend in a green bottle and keep adding all the green-smelling oils you can find. You will have a green note blend that you can use in place of lily-of-the-valley, calyx, or fern scent.

Musk can be replaced by amber, ambrette seed, angelica root, ambergris, or spikenard.

When you work with different scents, it is important to clear your olfactory palate. Just as wine tasters use white bread or crackers to clear their palates between tasting different wines, or sushi eaters take a bit of gari (pickled ginger) between tasting different types of fish, perfumers must clear their olfactory palates to keep their sense of smell tuned.

I keep a small piece of wool or a 100 percent wool scarf close at hand whenever I work with scents in a creative way. At regular intervals I hold the fabric over my nose and mouth and take a few breaths. The wool effectively filters the air and cleanses the palate, preparing the nasal passage for optimum appreciation of the next scent. A small piece of natural sea salt on the tongue can have a similar effect. I prefer the chunky type of sea salt, although this can be hard to find. Some perfumers clear their palates by sniffing fresh coffee beans. All of these methods work. I recommend you experiment with each method and choose the one that seems to work best for you.

When working with scents, always be sure to step outside for a breath of fresh air every hour or so. The fresh air will clear your head, renew your creativity, and preserve your scent acuity.

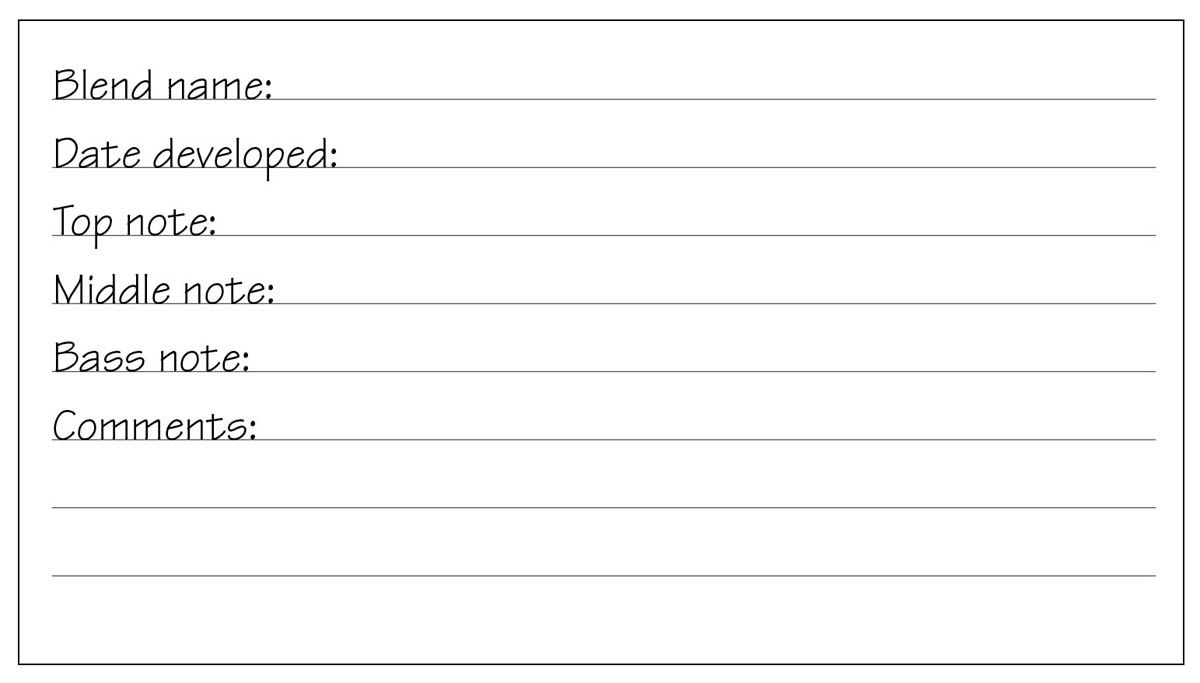

Always take notes when experimenting with your oils. I use a card file and keep my formulas written on index cards; you can also enter notes on a computer later (away from the oils), if desired. Use the same recipe format so you can compare the middle, top, and bass notes easily. It is tragic to create a beautiful blend and not remember how you did it. Each drop makes a difference.

On page 156 is a sample card. On it, you’d record the name of each oil you use in a formula, along with the exact number of drops. A typical proportion is 30 ml (1 ounce) perfume alcohol and 100 drops of essential oils.

Using this or a similar format, you can perform a laboratory experiment or create a spontaneous work of art. You will find what feels most comfortable for you and develop your own unique style.

There are “formulas” to perfumery just as there are “formulas” to music, fine cuisine, and the arts. Certain combinations just work: In music a repeat phrase or a return to the chorus line makes a melody pleasing to the ear; in visual art, analogous color schemes please the eye. Sometimes art is shocking or dramatic, and there is also a formula for that.

Study similarities in top, middle, and bass notes. Look at the common denominators. As you become familiar with the formulas, you will begin to understand the language of scent used by perfumers for hundreds of years.

I always begin with bass notes and combine 3 to 10 different substances. If the blend lasts on a blotter for more than three days, I consider it a good fixative. A rule of thumb is that the bass should never equal more than 20 percent of the total.

Think about your favorite perfumes. What are some of the qualities of perfumes you like? Are they sweet? Are they light and fresh or deep and amberlike? Do you want your creation to be sweet? green? fresh? ancient? rich? musty?

This is a creative place. Let your mind, your emotions, your imagination, and your memory all work together here. Some perfumers listen to inspirational music as they “compose” a new scent.

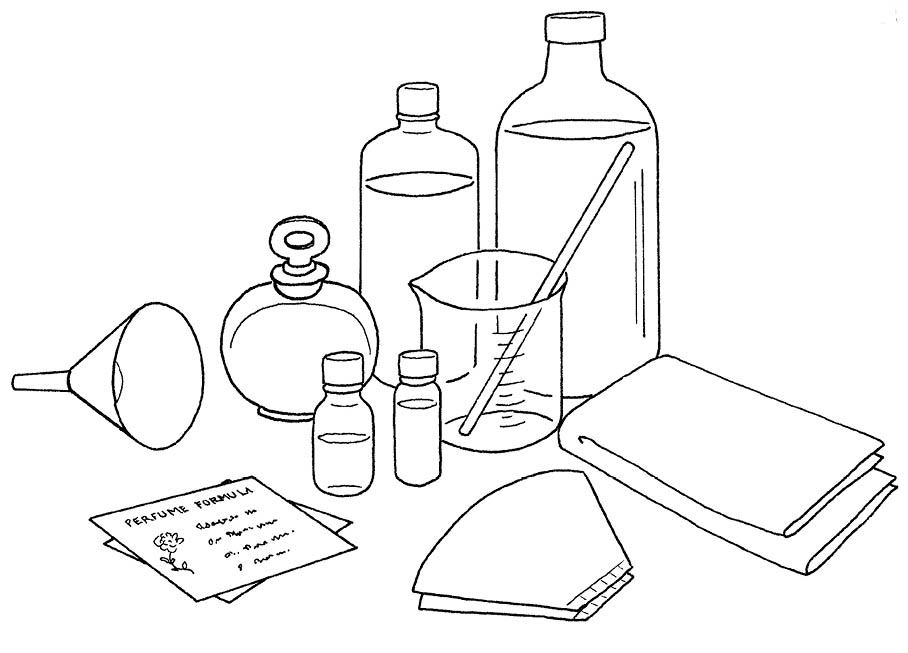

To conduct the following experiments prepare all your equipment and ingredients and create some quiet, uninterrupted time.

Most of the equipment needed for blending perfumes can be found right in your own kitchen. You might want to reuse old perfume bottles or search antique shops for unusual ones to fit your blend.

To begin your blending, you will need to assemble the following:

For this perfume, use standard proportions: 70 percent alcohol base, 20 percent water, and 10 percent essential oils.

To build your perfume from the bottom up you will begin with your bass notes, which should amount to no more than 20 percent of the total formula. Sixty percent of the formula should be built from middle notes, and the remaining 20 percent or so will be the top notes.

The commercially marketed fragrance products we know as perfumes are usually a mix of aromatic oils in a 75 to 95 percent alcohol solution. Real perfume, the finest and most expensive of these products, has a concentration of aromatic oils greater than 22 percent. Eau de perfume has a 15 to 22 percent concentration, and eau de toilette has an 8 to 15 percent concentration. The most diluted is cologne, which contains less than 5 percent aromatic oils, and some water.

For commercial purposes, extending the essences in alcohol is cost effective, but you can create your own custom blends with or without alcohol. Some fine perfumeries use only essential oils, adding no alcohol or other diluents. Others feel that pure essences are too strong to be enjoyed properly and must be diluted in alcohol.

Oil-based perfumes dating back to ancient Egypt are gaining in popularity. The main advantage of oil-based perfumes is you can melt beeswax into them for a solid balm, or add the oil-based perfume to creams, body oils, or bath salts.

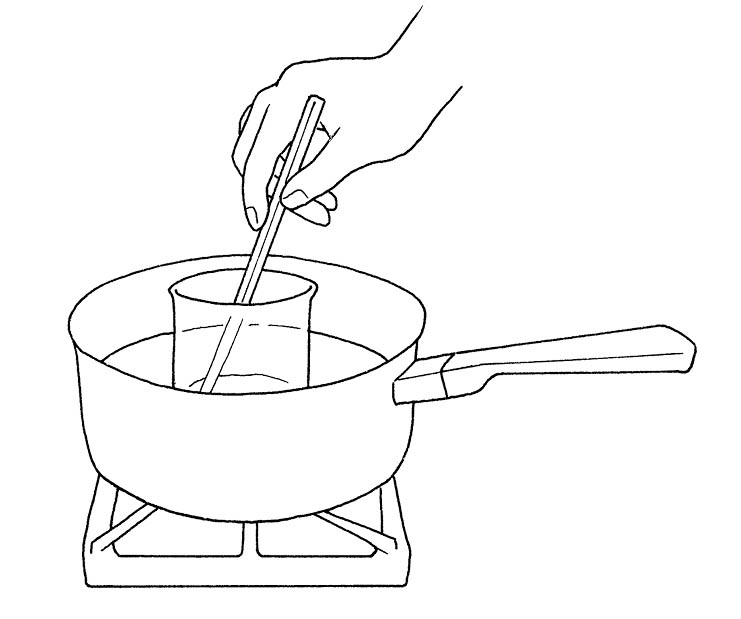

The disadvantage of oil-based perfumes is the necessity of heating solids and resins to blend, as opposed to the easier solvent reaction response of alcohol-based perfumes.

For this perfume you will use jojoba oil as your base or carrier oil.

When making oil-based perfumes, you may find it necessary to melt a thick or solid resin in the jojoba base oil. To do this, place the beaker of oil and resin in a saucepan of boiling water and stir constantly.

Solid perfumes or unguents are easy to create by just adding a little melted beeswax to the liquid perfume.

Determine proportions using this formula: 100 drops of essential oil to 30 ml (1 ounce) of carrier or base. The base will consist of 1 part beeswax to 4 parts jojoba for a slightly hard, solid product. For a softer solid, adjust the proportion to 1 part beeswax to 5 parts jojoba.

If you’re making solid perfume, strain the melted beeswax-jojoba mixture through a piece of cheesecloth to filter out any sediment.

In 1988 I attended “Future Scents,” an aromatherapy conference in southern California. One of the lecturers was John Steele, an enthusiastic scholar of archaeology, anthropology, and geology. John spoke of our language’s lack of vocabulary to describe scent. He pointed out how a more descriptive language could help us to better communicate about odors and describe more eloquently what our noses are sensing. I thought this was a fabulous idea, and started working on this new vocabulary right away.

I have been collecting a growing dictionary of scent terms and here share what I have compiled so far. Some of these words are “borrowed” from vintner’s terminology; many are adapted from French, the language with the most extensive scent vocabulary. Many of these words express abstract perceptions. Adding some of them to your vocabulary will enable you to express more fully what your nose communicates to you.

Accord. A balanced complex of three or four notes that lose their individuality to create a completely new, unified odor impression.

Adaptation. A tolerance to a particular perfume or scent so that it becomes unrecognizable.

Alcohol. Smelling of rubbing or ethyl alcohol.

Aldehyde. A synthetic scent with a rich opulence; a recognizable top note with a lemony or lemongrass scent.

Animal note. A sensual, heady bass note associated with the animal source oils: musk, civet, ambergris, and castoreum. Smelling of fecal odors. Animal notes can also be achieved from vegetable sources such as angelica, cistus, ambrette, and jasmine.

Anisic. Having a licorice-like odor of aniseed or fennel.

Balsamic. Having the sweet, soft, warm odor of resins.

Bass note. This is the bottom note and may show great tenacity. It acts as a fixative. Also called the dry-out note, it may occur only after several hours, and may continue for several days.

Blue. A scent in nature that is very elusive and hard to capture. Blue smells synthetic: total fantasy, as cool blue, blue water, rain, blue sky, dry seaweed scent.

Boeuf. A bad smell, like rotten meat (from the French word for “beef”).

Bouquet. A subtle, well-balanced blend of two or more fragrances. In French, the term refers to the combined floral quality of a smell.

Camphorous. Smelling of camphor, like mothballs.

Chypre. Pronounced SHEE-pra. A fragrance blend described as heavy and clinging with a flowery characteristic. A fruity eau de Cologne with an oakmoss bass.

Citrus. The fresh tangy smell of lemon, lime, orange, and so on. Citrus smells are considered antierogenous.

Cool. A term to describe outdoorsy scents such as green leaves after a rain, bracing mint notes, and citrus.

Cush. A funky still smell of residue from the last distillation; a sulfur smell.

Diffusion. A spontaneous vibrancy that causes a fragrance to radiate around your being.

Dry. A term to describe a fragrance that lacks sweetness, for instance one with woody notes.

Dry-out note. The residual odor left after the volatile components have evaporated.

Earthy. The aroma of freshly turned soil. The scent is achieved with oakmoss, patchouli and vetiver, or spikenard.

Erlenmeyer flask. A laboratory glass (aka vas de Florentine) used to catch the finished distillation of water and oil.

Essential oil. Essence; etheric oil; volatile oil.

Evaluate. In perfume testing, short little sniffs rather than long, deep inhalations are used for evaluation.

Factice. An oversize display perfume flacon (bottle); it holds tinted liquid.

Fixative. Derived from resins, mosses, and roots, fixatives modify the evaporation rate of a perfume’s note-giving element and make the scent lasting.

Florentine vase. Also called a Florence container and Erlenmeyer flask, a container used in the distillation process to catch the completed distillation of water and oil.

Foresty. Resembling the odor of wood, or the woods.

Fresh. A brisk, lively character of citrus or green composition.

Fruity. Any of the sweet fruit smells, such as apple and orange.

Green. A grasslike scent: dry, clean, and bright.

Herbaceous. Having an odor of herbs and garden plants (from the Greek forbea, meaning “pasture”).

Jagged edges. Prominent notes; failure to blend; lacking synergy.

Ketones. Jagged, powerful, medicinal, sharp, and abrasive.

Leather. Musky odor with a distinct smell of animal hides.

Marriage. The interval of time that ensures proper blending. For a fragrance to blend properly, it needs a few days to “marry” or “age.”

Mellow. A fragrance that has achieved a perfect balance; a smooth, rich fragrance.

Metallic. Having a cool, clear effect, like a steel pan after it’s rinsed with cool water.

Middle note. This is the bouquet or heart note composed of leaves and flowers; it may occur for two to three hours.

Mossy. Earthy, green, humus smelling.

Mousy. Not a good smell; a bit animal-like.

Note. A single impression in fragrance; a vibration.

Oriental spice. A classification of perfumes with a common theme of amber-patchouli-vanilla in the bass note, and cinnamon and spices on top.

Peppery. Hot and spicy; exotic. Scents of black or green pepper.

Pot odor. In French, vegetalle. A sulfury odor present in an essential oil or floral water immediately upon distillation.

Powdery. Having a rather indistinct odor. A certain blend of florals similar to the smell of baby’s powder or a baby’s head attains this highly desirable smell.

Pungent. Piercing and spicy; a smell with a hot character similar to pepper.

Refined. Having an exquisite quality. Pursuing perfection.

Relaxing. Calming and soothing to the emotions.

Rich. Full, with intensified depth and harmony.

Rose scent of Mary. A religious idea of what Mary’s natural scent is.

Round. Perfectly toned and complete in effect.

Scent of sanctity. A saint’s natural bodily emanations, or those of a spiritually evolved being.

Sharp. A peak or certain blend that is too strong; needs softening.

Sniffing. The act of inhaling in short little drafts to get the effects of an odor. See evaluate.

Soft. A very light, innocent effect; bois de rose is an example.

Tropical fruit. A difficult-to-achieve scent that blends oils, fruits, and flowers of Indian origin: specifically kewda and champa oils.

Warm. An aroma with a rich, heating action.

Pick red rose petals and place them in a bottle of pure alcohol. When the alcohol has absorbed the rose color, hold or “fix” it by placing the container of alcohol in the freezer for a few hours. Use the colored alcohol to color a perfume. Experiment with other colors. Wilted petals of purple iris make a lovely robin’s egg blue. Violet flowers of wisteria make lavender, and pomegranate seeds yield a violet-fuchsia.