25

Collage, Bricolage, Assemblage

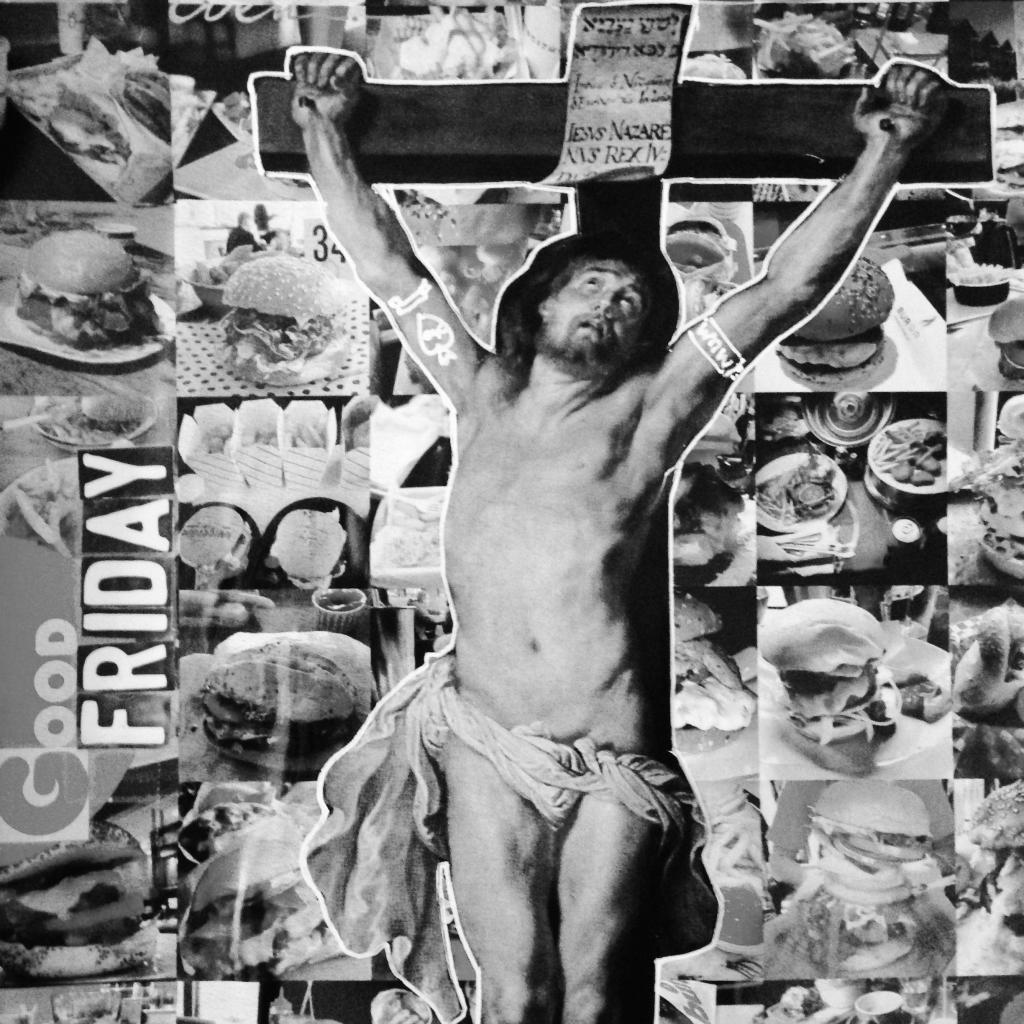

I am and have always been a maker of art. I paint badly, and I draw just as well. I make sculptures and curio boxes out of found materials. But mostly I make collages. For the past twenty-five years, I’ve made one almost every day.

The habit developed out of journaling, something else I have done for most of my life. I used to write every day about the usual stuff: concerts and other events I’ve attended, frustrations, desires, quotes, and ideas—all the things you put down just for yourself. As time went on, I began sticking bits of ephemera alongside my writing, like ticket stubs, wrappers, odd things I picked up in the street. Then I began drawing in them as well. Journaling was a calming way of reflecting on my life. One day, I decided I wouldn’t write. Instead, I created a collage. I’m a magazine junkie, particularly art and fashion magazines, so I had plenty of images to work with. When I finished the collage, I tried to write on it, but the glue hadn’t dried and the pen wouldn’t write. Instead, I cut letters out of a magazine and reduced my day down to three of four things: work, dinner with so and so, art class, whatever. The exercise captured the essence of my day with a few images and some cut-out letters, and eventually this became my habit. Then I discovered Peter Beard.

Beard is an American photographer, artist, writer, and diarist. He lived in Kenya for a time, in a tent on property belonging to Karen Blixen, who is most known for her 1937 memoir Out of Africa and the film of the same name. Beard was a fashion and rock photographer who moved in New York art circles, but his diaries are what captured my attention. He keeps amazing diaries full of images, his own and taken from elsewhere, combined with all sorts of notes, ephemera, and hand-drawn figures. His African wildlife photography is world famous and commands huge fees. So do massive, blown-up images of pages from his journals, which he customizes at his gallery shows with hand-smeared blood, stones, snakeskin, and anything else he fancies. A friend once took me to an opening of one of his rare Los Angeles shows and I was blown away by his creativity. His work became an inspiration to my own art. So, I refined my collages by reducing the words and using found images and objects to capture my thoughts and feelings on any given day. I do it almost daily, and it is probably my most disciplined habit.

The term collage is said to have been coined by Pablo Picasso and his friend Georges Braque at the turn of the twentieth century, when collage was brought into the fine arts world. Picasso’s 1912 piece Still Life with Chair Caning is the first example of collage in fine art. Although it has been around for a long time, collage has taken on a new level of significance since its inclusion in the processes and techniques of modern art.

Something about collage points to the fragmented reality of contemporary life. Many disparate things are forced to live side by side. In my own collaging, I seldom have a vision for what I want to make. I just let the random available images express what I feel.

Maybe that’s what collaging is—dealing with the randomness of life. The iPod Shuffle first debuted with a similar purpose. It was the first piece of software built for randomness and it became a metaphor for how to deal with the unpredictable and learn to live with what it brings you, for it will soon change to another song in a few minutes.

Bricolage is another French word that captures both a form of art and a philosophical theory. It essentially means “do-it-yourself” and is connected to the creation of an artwork or theory from a diverse range of available things. The term became popular among postmodern philosophers such as Jacques Derrida and Claude Lévi-Strauss. Strauss used it to describe a method of thought that opposes what he regarded as the mechanized thinking of the modern world, which was about ends and means. For him, bricolage involved using old materials and ideas to solve new problems.

A bricoleur uses whatever materials are available to generate new meaning in the world. Early twentieth-century art movements such as Surrealism, Dadaism, and Cubism all bear traces of bricolage. But it was in the 1960s that bricolage art took on a more political shape. Bricolage artists made sculptures and other pieces out of rubbish to criticize the art world’s rampant commercialization. They made works out of everyday trash in hopes of asserting the value of the ordinary and devaluing the art object itself.

This same idea was explored in the early 2000s by British artists Sue Webster and Tim Noble, who created a series of sculptures from the trash they found in the neighborhood around their London home. At first glance, their sculptures simply look like piles of trash, mountains of things that characterize our throwaway culture. But the sculptures hold a second element. They are in fact precise constructions that can only be seen when light is shined on them, turning meaningless trash into meaningful shadows of people and other scenes from everyday life.

The artists used these sculptures to spotlight our complicity in trash culture, the small, daily ways we contribute to the world’s litter and the increasing ecological challenges raised by our carelessness, all because of our love affair with the disposable. Their abstract sculptures require a close viewing and a willingness to look beyond darkness into light. Webster’s and Noble’s constructions signal that perhaps our own inventiveness and creativity could light the way to another way of living if we face the choices that we often leave in the dark. They are an invitation to consider that the clues and answers to a better way of living lie around us in the everyday, the ordinary, and the throwaway.