39

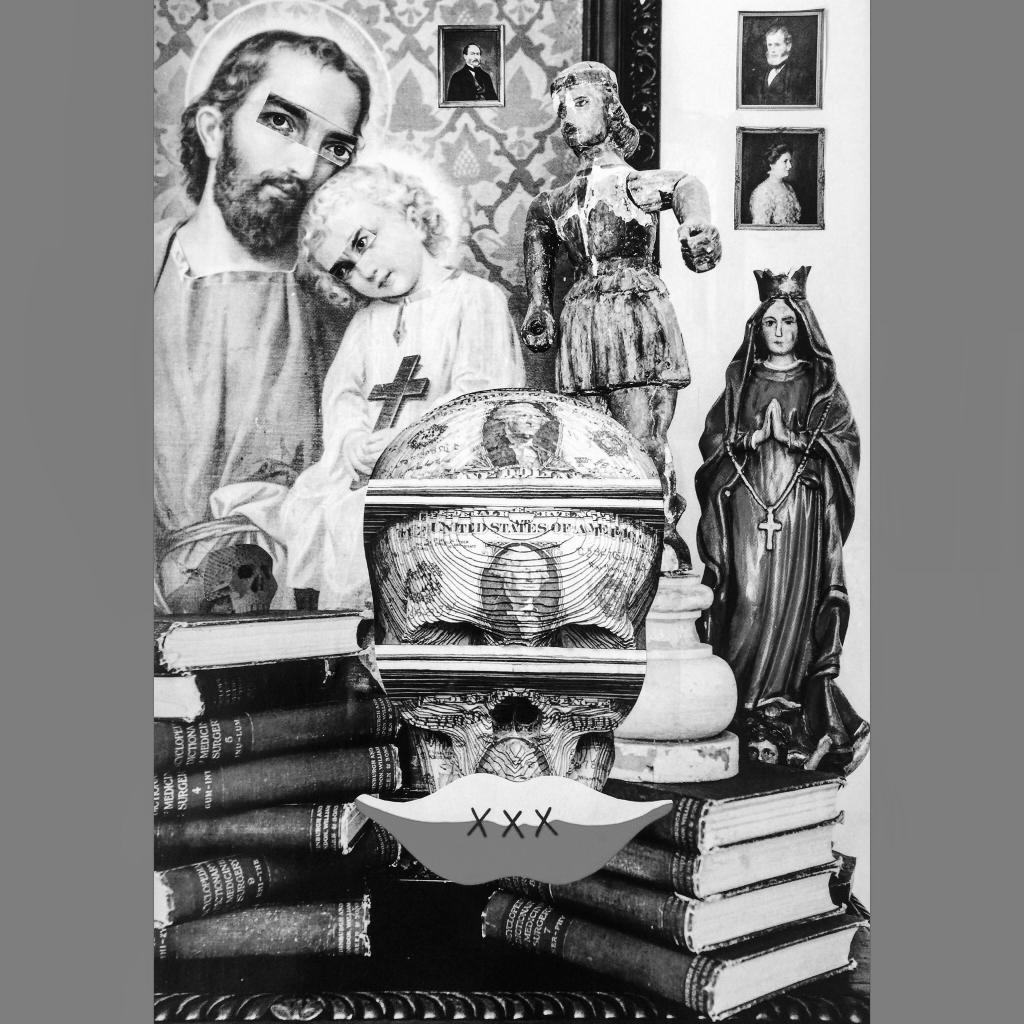

Losing Jesus

When I first started exploring religion, I was looking for clues that pointed toward things I felt I were missing in my life, or at least things I didn’t have sorted out and wanted to change. I thought Christianity might offer those clues, but ultimately it got in the way. Christianity, or the form of Christianity I was exposed to, was an all-encompassing system of belief. I embraced it for a while, though it never felt quite right.

I had been on the road with AC/DC for a few years around then, so I had saved enough money to live on without working. So having decided that a change was necessary and with all that extra time on my hands, I left the world of rock and roll and embarked on another leg of life’s journey. I became involved in a church. It was nondenominational, formed out of the Calvary Chapel and Vineyard Churches that littered Southern California. Products of the 1960s counterculture, those churches’ understanding of Jesus had emerged from the ashes of hippie idealism. In spite of rejecting institutional religions as relics of a bygone age, 1960s youths didn’t exclude spirituality from their searches for new ways of life. While the mainstream church and many radical theologians of the time declared God was dead, a spiritual revolution was underway in youth culture in the image of a long-haired revolutionary Jesus preaching love and good works. They may have rejected organized religion, but “Jesus Is Just Alright,” as the Doobie Brothers declared in 1966.

The slow divide between religion and spirituality began in the 1960s, as new churches formed that preached a more spiritual Jesus of relationship, community, love, and grace. These churches were not mainstream; their message was new and countercultural. But their hippie idealism was married with a more conservative theological perspective that emphasized sin, dark understandings of the world, and human nature. People were accepted as part of the new tribe as long as they were ready to leave the past firmly behind and get a new life with Jesus.

Post-AC/DC, the first cracks in my new religious armor came through music. I was still linked to my musical past through some of my Los Angeles Christian friends, who played in a band and had a deal with a Christian record company. We sang and wrote songs together, but it was hardly rock ’n’ roll. Their Beatles-esque sound got them a bit of a following and a fair amount of trouble with some church leaders, who thought them too worldly and devilish. At the time, in the early 1980s, feelings ran high about secular society and the dangers of popular culture—particularly pop music’s demonic nature.

Disillusioned by our experiences, my friends and I began to wonder what was really going on under this veneer of supposedly cool religiosity. We had been raised on pop music, so letting it go was not an option. I quickly realized that many Christian leaders had done little critical thinking about culture and what was really going on in society. Things were reduced to pietistic and outdated mentalities of us versus them, the sacred/secular divide. But these were the people who were supposedly collapsing those divides and blurring the lines! The very Jesus they were worshipping had been given to them by the youth culture. Yet here they were, trashing it and declaring it devoid of any goodness.

I tried to focus on the positives. I voraciously read philosophy, theology, and sociology. I was at the church every time the doors opened. In a church like this, leadership was an open opportunity conferred upon people on the basis of friendship, preference, and access to networks. I was well liked and eager to contribute, so I rose through the community’s ranks.

Once, I was asked to speak at a Wednesday meeting. I’d never before spoken in public—I was unbelievably shy—but for some reason I agreed and found myself not the least bit nervous. And I did well. I discovered that it was easy to speak in a public setting—much easier than in the intimacy of real life. Before long, I was the center of it all. I was appointed to leadership and my life became the business of professional Christian ministry: preaching, teaching, and running a church. This was something I had never desired or imagined, but it just sort of happened.

I still felt uneasy about the church, but I continued to push that feeling down. For a while, the newness and the learning curve of everything distracted me from my nagging doubts. I forced myself into ways of thinking and living that I was told were good and right, but eventually I grew to hate myself for my internal resistance to my new world. I figured the problem was me. That’s the tyranny of self-doubt: you seldom give yourself the credit for what you think and feel. It’s a heavy weight to carry, and carry it I did.

It’s funny how something small can come along and, in a moment, entirely undo your life. A word spoken in passing, an unexpected situation, someone you meet, a movie you watch—it can pull back the curtain on your existence and expose the fragility of what you are trying to hold together. I was getting lost in religion—lost in the business of church, and not in a good way. I was surrounded by people who saw the world as a dark and dangerous place full of temptations and godlessness, but I did not see the world the way they did. I did not fear the world that way. For all my melancholy, I really like life—the gritty realities of living. I also have little problem with people whose lives don’t follow the same pathway as mine—that’s what makes things interesting. Homogeneity has never appealed to me. But I was feeling the pressure of these peoples’ expectations, their assumptions about how I should look, act, and think.

I was living in the world of shoulds. “God commands . . .” “Jesus wants you to do this and not that,” “Paul says . . .” It was all wearing on me. I was trying to live up to something that was beyond me, and I slowly realized I didn’t believe much of what I was being told, or even what I was saying myself. I was trying to be faithful to the community and the powers that be, but I didn’t agree with their perspectives. The more I read, the more I realized there many other ways to think.

During this critical juncture in my life—a time when I was looking for something, anything, to guide me through whatever lay ahead—three things came in quick succession that set me on a new path: a line of Scripture, an idea in a book, and a cassette tape.

The line of Scripture came from the story in the Gospel of Luke in which Mary, Joseph, and Jesus joined other pilgrims to celebrate the Passover festival in Jerusalem. After it ended and they all headed home, the text reads nonchalantly, “The boy Jesus stayed behind in Jerusalem, but they were unaware of it. Thinking he was in their company, they traveled on for a day” (Luke 2:43–44). It’s a simple recounting of an ancient story, one I had read many times before, but this time it jumped out at me. They had lost Jesus in Jerusalem, then went back to look for him. That’s exactly how I felt. Here I was, up to my neck in the business of the church, but I felt distanced from the very thing that had brought me there in the first place.

Organized Christianity sometimes makes much more of Paul than it does of Jesus. Of course, Jesus gets honorable mention—he’s hard to ignore completely—but most of the time, conversations about what the church should be become an investigation of Paul’s views on the topic. I missed Jesus and had a gnawing sense that I needed to recover something central to me about how all this religious stuff I had found myself wrapped up in fit with who I wanted to be. As clueless as I was, I didn’t quit—and I still haven’t. I’m not sure why.

Around the time I had this epiphany with the story in Luke, I came across a quote from Einstein that said, “Every man must strive to be a voice and not an echo.” There it was: another little clue. There was something uniquely for me in that invocation—encouragement to find my own voice, speak my own truth, and not simply repeat what others say. The clue to being yourself is to own your thoughts and feelings, to work out your true beliefs, even if they contradict conventional wisdom.

Finding your voice can take a lifetime. Perhaps it begins in emulation or imitation; we tend to model ourselves on those we value. It’s like being in a band. You start by learning the songs of your musical idols, building up enough skill until you dare to think you could write a song too. That’s the day you come into your own as musician and start to define your own particular sound and feel. I understood the process when it came to music; I hadn’t thought it was the same for the rest of life. I wasn’t sure how to begin, but I sure as shit wanted to try.

Maybe a month or a year later, a friend gave me a cassette tape. It was a recording of a talk on Christian leadership, a topic I was less than enthusiastic about at the time. But it was from a speaker outside the circles I moved in and my friend recommended it, so I gave it a chance. It began: “The task of the Christian leader . . . is to guard the great questions.” That’s about as far as I got. I have no idea what else that tape said, but those words have been indelibly inscribed on my heart ever since. Guard the great questions. That’s not an earth-shattering idea, you might be thinking. And you are right. But I had immersed myself in an understanding of Christianity that had no interest in questions, only answers. God had answers for everything. All you needed to know about God, yourself, the world, and others could be found in the Bible and modeled in the narratives of Jesus. Questions don’t need to be guarded; just find the answers and everything will slide into place. But this reminder—to cherish and guard the questions that make up our faith, lives, and very existences—shook me. What if you don’t ask the right questions, or even know what they are? What are the great questions? I didn’t know.

The speaker was referring to the questions of ultimate meaning—the dilemma of the human condition, the trauma of life—that constantly arise in the human psyche. But I took those words and personalized them. What are the great questions I am asking of the world, of life, of God? “Listen to your life,” wrote theologian Frederick Buechner. “See it for the fathomless mystery it is.” I hadn’t been listening to my life. Well, I might have been listening, but certainly had not been paying attention. Until now.

This quickly became the basic framework for a new direction in my life down a bumpy road out of particular forms of Christian faith. Since the late 1980s and early ’90s, those three kernels of ideas have shaped my life.

So, I left that church. I’ve since left a couple more, some of them well and others not so well. But this one I left by moving away, and I started another with a group of friends. Well, it wasn’t a church—I started a project that has been ongoing for the last couple decades. It’s built around finding other ways of thinking and practicing religion, searching instead for religionless forms of faith and post-theistic expressions of religion.

One of the first things I did after leaving was commit to a theological education. I decided to explore the questions that interested me, so I could research and reflect on all the aspects of religion and theology I wanted to investigate. I went to seminary—not because I wanted a degree, but for access to information and ideas beyond my reach.

I arrived at seminary armed with questions and a whole load of answers I had been given that I knew didn’t work for me. I set about the long process of refining my interests down to their core and reframing what I thought about life, God, and religion. The questions I guard are held between the folds of those three elements. I threw away old maps and set out to chart new ones. You can get lost without a map, but getting lost is the beginning of learning; it’s how you create new maps.

At seminary, I wanted to explore the new cultural contexts that religion and Christianity found themselves in. I wanted to better understand this new deterritorialized world of late twentieth-century life in which the old theological codes no longer worked. This world was shaped by popular culture, by technology that has reframed our sense of self in relation to others and to the sacred; learning about religion means learning about the culture from which it came. French feminist philosopher Julia Kristeva, in her 2006 book This Incredible Need Believe, named our new context of belief as the dichotomy between the “need to believe” and the “desire to know.” Both are driven by a hunger to make meaning in our lives amidst the reality of a world filled with new knowledge, emerging complex science, and ideas that challenge our age-old views. Everyone is a skeptic, and we are all atheists at least once a day, even if we say we believe in God.

So, I set out on this new adventure of discovery not knowing where I was headed, but with a hunger to recover what I had lost and to discover other things about myself, life, belief, and God. I wanted to reconcile my various interests: music, art, culture, theology, philosophy, religion, belief. My interest in philosophy, Camus’s notion of the absurd, Jean-François Lyotard’s rejection of meta-narrative, Nietzsche’s nihilism—all these ideas that fired my curiosity and passion—how could they fit together? Were there ways of thinking about religion that felt more cohesive to me? Could a community be shaped out of nonbelief, out of brokenness? Could a space be created in which people weren’t fixed but accepted? Could space be made for doubt, atheism, or a/theism?

I wanted to examine what the writer Fernando Pessoa called the “sickness of the eyes”: that dullness born of familiarity, the tacit acceptance of the way things are. His remedy for this was poetry. Poetry was his process of unlearning. Poets reminds us what we already know and interpret what we already understand. Jesus was my poet; he helped me in the process of unlearning, addressing the sickness of my eyes and inviting me to cultivate a sense of the world around me. That was what I liked about Jesus, his “this-worldliness.” For him, there was no escape from life, there was no need for any way out. What we need is a way in, a way to get deeper into life. Jesus was the poet who came to heal the sickness of our eyes by telling us what we already knew. “You have heard it said, but I say unto you,” he said (Matt 5:27–28). He was pointing to what was right under our noses so that we could see again. I wanted to see again. I want to see.