Two kinds of books are ordinarily written for pastors and church leaders. One kind lays out general biblical principles for all churches. These books start with scriptural exegesis and biblical theology and list the characteristics and functions of a true biblical church. The most important characteristic is that a ministry be faithful to the Word and sound in doctrine, but these books also rightly call for biblical standards of evangelism, church leadership, community and membership, worship, and service.

Another category of book operates at the opposite end of the spectrum. These books do not spend much time laying biblical theological foundations, though virtually all of them cite biblical passages. Instead, they are practical “how-to” books that describe specific mind-sets, programs, and ways to do church. This genre of book exploded onto the scene during the church growth movement of the 1970s and 1980s through the writing of authors such as C. Peter Wagner and Robert Schuller. A second generation of books in a similar vein appeared with personal accounts of successful churches, authored by senior pastors, distilling practical principles for others to use. A third generation of practical church books began more than ten years ago. These are volumes that directly criticize the church growth how-to books. Nevertheless, they also consist largely of case studies and pictures of what a good church looks like on the ground, with practical advice on how to organize and conduct ministry.

From these latter volumes I have almost always profited, coming away from each book with at least one good idea I could use. But by and large, I found the books less helpful than I hoped they would be. Implicitly or explicitly, they made near-absolutes out of techniques and models that had worked in a certain place at a certain time. I was fairly certain that many of these methods would not work in my context in New York and were not as universally applicable as the authors implied. In particular, church leaders outside of the United States found these books irritating because the authors assumed that what worked in a suburb of a U.S. city would work almost anywhere.

As people pressed me to speak and write about our experience at Redeemer, I realized that most were urging me to write my own version of the second type of book. Pastors did not want me to recapitulate biblical doctrine and principles of church life they had gotten in seminary. Instead, they were looking for a “secrets of success” book. They wanted instructions for specific programs and techniques that appealed to urban people. One pastor said, “I’ve tried the Willow Creek model. Now I’m ready to try the Redeemer model.” People came to us because they knew we were thriving in one of the least churched, most secular cities in the U.S. But when visitors first started coming to Redeemer in the early and mid-1990s, they were disappointed because they did not discern a new “model” — at least not in the form of unique, new programs. That’s because the real “secret” of Redeemer’s fruitfulness does not lie in its ministry programs but in something that functions at a deeper level.

Hardware, Middleware, Software

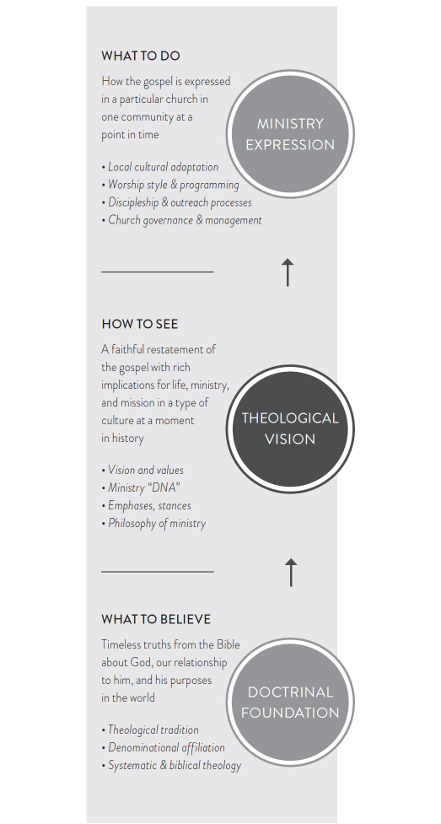

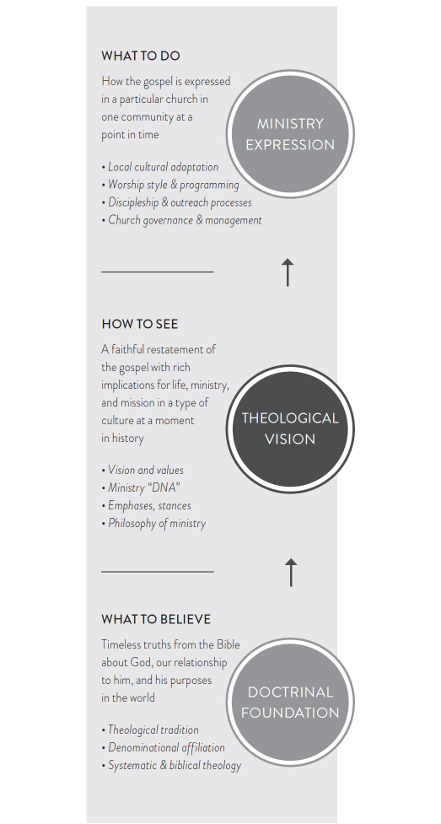

What was this deeper level, exactly? As time went on, I began to realize it was a middle space between these two more obvious dimensions of ministry. All of us have a doctrinal foundation — a set of theological beliefs — and all of us conduct particular forms of ministry. But many ministers take up programs and practices of ministry that fit well with neither their doctrinal beliefs nor their cultural context. They adopt popular methods that are essentially “glued on” from the outside — alien to the church’s theology or setting (sometimes both!). And when this happens, we find a lack of fruitfulness. These ministers don’t change people’s lives within the church and don’t reach people in their city. Why not? Because the programs do not grow naturally out of reflection on both the gospel and the distinctness of their surrounding culture.

If you think of your doctrinal foundation as “hardware” and of ministry programs as “software,” it is important to understand the existence of something called “middleware.” I am no computer expert, but my computer-savvy friends tell me that middleware is a software layer that lies between the hardware and the operating system and the various software applications being deployed by the computer’s user. In the same way, between one’s doctrinal beliefs and ministry practices should be a well-conceived vision for how to bring the gospel to bear on the particular cultural setting and historical moment. This is something more practical than just doctrinal beliefs but much more theological than how-to steps for carrying out a particular ministry. Once this vision is in place, with its emphases and values, it leads church leaders to make good decisions on how to worship, disciple, evangelize, serve, and engage culture in their field of ministry — whether in a city, suburb, or small town.

Theological Vision

This middleware is similar to what Richard Lints, professor of theology at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, calls a “theological vision.”1 According to Lints, our doctrinal foundation, drawn from Scripture, is the starting point for everything:

Theology must first be about a conversation with God . . . God speaks and we listen . . . The Christian theological framework is primarily about listening — listening to God. One of the great dangers we face in doing theology is our desire to do all the talking . . . We most often capitulate to this temptation by placing alien conceptual boundaries on what God can and has said in the Word . . . We force the message of redemption into a cultural package that distorts its actual intentions. Or we attempt to view the gospel solely from the perspective of a tradition that has little living connection to the redemptive work of Christ on the cross. Or we place rational restrictions on the very notion of God instead of allowing God to define the notions of rationality.2

However, the doctrinal foundation is not enough. Before you choose specific ministry methods, you must first ask how your doctrinal beliefs “might relate to the modern world.” The result of that question “thereby form[s] a theological vision.”3 In other words, a theological vision is a vision for what you are going to do with your doctrine in a particular time and place. And what does a theological vision develop from? Lints shows that it comes, of course, from deep reflection on the Bible itself, but it also depends a great deal on what you think of the culture around you. Lints offers this important observation:

A theological vision allows [people] to see their culture in a way different than they had ever been able to see it before . . . Those who are empowered by the theological vision do not simply stand against the mainstream impulses of the culture but take the initiative both to understand and speak to that culture from the framework of the Scriptures . . . The modern theological vision must seek to bring the entire counsel of God into the world of its time in order that its time might be transformed.4

In light of this, I propose a set of questions that can guide us in the development of a theological vision. As we answer questions like these, a theological vision will emerge:

• What is the gospel, and how do we bring it to bear on the hearts of people today?

• What is this culture like, and how can we both connect to it and challenge it in our communication?

• Where are we located — city, suburb, town, rural area — and how does this affect our ministry?

• To what degree and how should Christians be involved in civic life and cultural production?

• How do the various ministries in a church — word and deed, community and instruction — relate to one another?

• How innovative will our church be and how traditional?

• How will our church relate to other churches in our city and region?

• How will we make our case to the culture about the truth of Christianity?

Our theological vision, growing out of our doctrinal foundation but including implicit or explicit readings of culture, is the most immediate cause of our decisions and choices regarding ministry expression. It is a faithful restatement of the gospel with rich implications for life, ministry, and mission in a type of culture at a moment in history. Perhaps we can diagram it like this (see figure):

Center Church

This book was originally published in 2012 as one of three sections of a longer work called Center Church. In that book, I presented the theological vision that has guided our ministry at Redeemer. But what did we mean by the term center church? We chose this term for several reasons.

1. The gospel is at its center. It is one thing to have a ministry that is gospel-believing and even gospel-proclaiming but quite another to have one that is gospel-centered.

2. The center is the place of balance. We need to strike balances as Scripture does: of word and deed ministries; of challenging and affirming human culture; of cultural engagement and countercultural distinctiveness; of commitment to truth and generosity to others who don’t share the same beliefs; of tradition and innovation in practice.

3. Our theological vision must be shaped by and for urban and cultural centers. Ministry in the center of global cities is the highest priority for the church in the twenty-first century. While our theological vision is widely applicable, it must be distinctly flavored by the urban experience.

4. The theological vision is at the center of ministry. A theological vision creates a bridge between doctrine and expression. It is central to how all ministry happens. Two churches can have different doctrinal frameworks and ministry expressions but the same theological vision — and they will feel like sister ministries. On the other hand, two churches can have similar doctrinal frameworks and ministry expressions but different theological visions — and they will feel distinct.

The Center Church theological vision can be expressed most simply in three basic commitments: Gospel, City, and Movement.5 Each book in the Center Church series covers one of these three commitments.

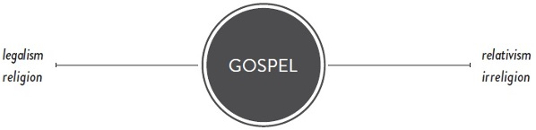

Gospel. Both the Bible and church history show us that it is possible to hold all the correct individual biblical doctrines and yet functionally lose our grasp on the gospel. It is critical, therefore, in every new generation and setting to find ways to communicate the gospel clearly and strikingly, distinguishing it from its opposites and counterfeits.

City. All churches must understand, love, and identify with their local community and social setting, and yet at the same time be able and willing to critique and challenge it. Every church, whether located in a city, suburb, or rural area (and there are many permutations and combinations of these settings), must become wise about and conversant with the distinctives of human life in those places. But we must also think about how Christianity and the church engage and interact with culture in general. This has become an acute issue as Western culture has become increasingly post-Christian.

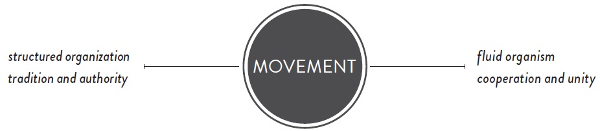

Movement. The last area of theological vision has to do with your church’s relationships — with its community, with its recent and deeper past, and with other churches and ministries. Some churches are highly institutional, with a strong emphasis on their own past, while others are anti-institutional, fluid, and marked by constant innovation and change. Some churches see themselves as being loyal to a particular ecclesiastical tradition — and so they cherish historical and traditional liturgy and ministry practices. Those that identify very strongly with a particular denomination or newer tradition often resist change. At the other end of the spectrum are churches with little sense of a theological and ecclesiastical past that tend to relate easily to a wide variety of other churches and ministries. All of these different perspectives have an enormous impact on how we actually do ministry.

The Balance of Three Axes

One of the simplest ways to convey the need for wisdom and balance in formulating principles of theological vision is to think of three axes.

1. The Gospel axis. At one end of the axis is legalism, the teaching that asserts or the spirit that implies we can save ourselves by how we live. At the other end is antinomianism or, in popular parlance, relativism — the view that it doesn’t matter how we live; that God, if he exists, loves everyone the same. But the gospel is neither legalism nor relativism. We are saved by faith and grace alone, but not by a faith that remains alone. True grace always results in changed lives of holiness and justice. It is, of course, possible to lose the gospel because of heterodoxy. That is, if we no longer believe in the deity of Christ or the doctrine of justification, we will necessarily slide toward relativism. But it is also possible to hold sound doctrine and yet be marked by dead orthodoxy (a spirit of self-righteousness), imbalanced orthodoxy (overemphasis on some doctrines that obscure the gospel call), or even “clueless orthodoxy,” which results when doctrines are expounded as in a theology class but aren’t brought together to penetrate people’s hearts so they experience conviction of sin and the beauty of grace. Our communication and practices must not tend toward either law or license. To the degree that they do, they lose life-changing power.6

2. The City axis (which could also be called a Culture axis). We will show that to reach people we must appreciate and adapt to their culture, but we must also challenge and confront it. This is based on the biblical teaching that all cultures have God’s grace and natural revelation in them, yet they are also in rebellious idolatry. If we overadapt to a culture, we have accepted the culture’s idols. If, however, we underadapt to a culture, we may have turned our own culture into an idol, an absolute. If we overadapt to a culture, we aren’t able to change people because we are not calling them to change. If we underadapt to a culture, no one will be changed because no one will listen to us; we will be confusing, offensive, or simply unpersuasive. To the degree a ministry is overadapted or underadapted to a culture, it loses life-changing power.

3. The Movement axis. Some churches identify so strongly with their own theological tradition that they cannot make common cause with other evangelical churches or other institutions to reach a city or work for the common good. They also tend to cling strongly to forms of ministry from the past and are highly structured and institutional. Other churches are strongly anti-institutional. They have almost no identification with a particular heritage or denomination, nor do they have much of a relationship to a Christian past. Sometimes they have virtually no institutional character, being completely fluid and informal. A church at either extreme will stifle the development of leadership and strangle the health of the church as a corporate body, as a community. To the degree that it commits either of these errors, it loses its life-giving power.

The more that ministry comes “from the center” of all the axes, the more dynamism and fruitfulness it will have. Ministry that is toward the end of any of the spectrums or axes will drain a ministry of life-changing power with the people in and around it.

As with the original publication of Center Church, my hope is that each of these smaller volumes will be useful and provoke discussion. The three volumes of the paperback series each correspond to one of the three axes.

Shaped by the Gospel looks at the need to recover a biblical view of the gospel. Our churches must be characterized by our gospel-theological depth rather than by our doctrinal shallowness, pragmatism, nonreflectiveness, and method-driven philosophy. In addition, we need to experience renewal so that a constant note of grace is applied to everything and our ministry is not marked by legalism or cold intellectualism.

Loving the City highlights the need to be sensitive to culture rather than choosing to ignore our cultural moment or being oblivious to cultural differences among groups. It looks at how we can develop a vision for our city by adopting city-loving ways of ministry rather than approaches that are hostile or indifferent to the city. We also look at how to engage the culture in such a way that we avoid being either too triumphalistic or too withdrawn and subcultural in our attitude.

Serving a Movement shows why every ministry of the church should be outward facing, expecting the presence of nonbelievers and supporting laypeople in their ministry in the world. We also look at the need for integrative ministry where we minister in word and deed, helping to meet the spiritual and physical needs of the poor as well as those who live and work in cultural centers. Finally, we look at the need for a mind-set of willing cooperation with other believers, not being turf conscious and suspicious but eagerly promoting a vision for the whole city.

The purpose of these three volumes, then, is not to lay out a “Redeemer model.” This is not a “church in a box.” Instead, we are laying out a particular theological vision for ministry that we believe will enable many churches to reach people in our day and time, particularly where late-modern Western globalization is influencing the culture. This is especially true in the great cities of the world, but these cultural shifts are being felt everywhere, and so we trust that this book will be found useful to church leaders in a great variety of social settings. We will be recommending a vision for using the gospel in the lives of contemporary people, doing contextualization, understanding cities, doing cultural engagement, discipling for mission, integrating various ministries, and fostering movement dynamics in your congregation and in the world. This set of emphases and values — a Center Church theological vision — can empower all kinds of church models and methods in all kinds of settings. We believe that if you embrace the process of making your theological vision visible, you will make far better choices of model and method.