At the main bases of the Baltic fleet, activity began long before dawn on the morning of Wednesday, October 25. The first of three large echelons of armed sailors, bound for the capital at the behest of the Military Revolutionary Committee, departed Helsingfors by train along the Finnish railway at 3:00 A.M.; a second echelon got underway at 5:00 A.M., and a third left around midmorning. About the same time, a hastily assembled naval flotilla, consisting of a patrol boat—the Iastrev—and five destroyers—the Metki, Zabiiaka, Moshchny, Deiatelny, and Samson—started off at full steam for the roughly two hundred-mile trip to Petrograd, with the Samson in the lead flying a large banner emblazoned with the slogans “Down with the Coalition!” “Long Live the All-Russian Congress of Soviets!” and “All Power to the Soviets!”1

Activity of a similar kind was taking place at Kronstadt. Describing the night of October 24–25 in that center of revolutionary radicalism, Flerovsky was later to recall:

It is doubtful whether anyone in Kronstadt closed his eyes that night. The Naval Club was jammed with sailors, soldiers, and workers. . . . The revolutionary staff drew up a detailed operations plan, designated participating units, made an inventory of available supplies, and issued instructions. . . . When the planning was finished . . . I went into the street. Everywhere there was heavy, but muffled traffic. Groups of soldiers and sailors were making their way to the naval dockyard. By the light of the torches we could see just the first ranks of serious determined faces. . . . Only the rumble of the automobiles, moving supplies from the fortress warehouses to the ships, disturbed the silence of the night.2

Shortly after 9:00 A.M. the sailors, clad in black pea jackets, with rifles slung over their shoulders and cartridge pouches on their belts, finished boarding the available vessels: two mine layers, the Amur and the Khopor; the former yacht of the fort commandant, the Zarnitsa, fitted out as a hospital ship; a training vessel, the Verny; a battleship, the Zaria svobody, so old that it was popularly referred to as the “flatiron” of the Baltic Fleet and had to be helped along by four tugs; and a host of of smaller paddle-wheel passenger boats and barges. As the morning wore on these vessels raised anchor, one after the other, and steamed off in the direction of the capital.3

At Smolny at this time, the leaders of the Military Revolutionary Committee and commissars from key locations about the city were completing plans for the capture of the Winter Palace and the arrest of the government. Podvoisky, Antonov-Ovseenko, Konstantin Eremeev, Georgii Blagonravov, Chudnovsky, and Sadovsky are known to have participated in these consultations. According to the blueprint which they worked out, insurrectionary forces were to seize the Mariinsky Palace and disperse the Preparliament; after this the Winter Palace was to be surrounded. The government was to be offered the opportunity of surrendering peacefully. If it refused to do so, the Winter Palace was to be shelled from the Aurora and the Peter and Paul Fortress, after which it was to be stormed. The main forces designated to take part in these operations were the Pavlovsky Regiment; Red Guard detachments from the Vyborg, Petrograd, and Vasilevsky Island districts; the Keksgolmsky Regiment; the naval elements arriving from Kronstadt and Helsingfors; and sailors from the Petrograd-based Second Baltic Fleet Detachment. Command posts were to be set up in the barracks of the Pavlovsky Regiment and the Second Baltic Fleet Detachment, the former to be directed by Eremeev and the latter by Chudnovsky. A field headquarters for overall direction of the attacking military forces, to be commanded by Antonov-Ovseenko, was to be established in the Peter and Paul Fortress.4

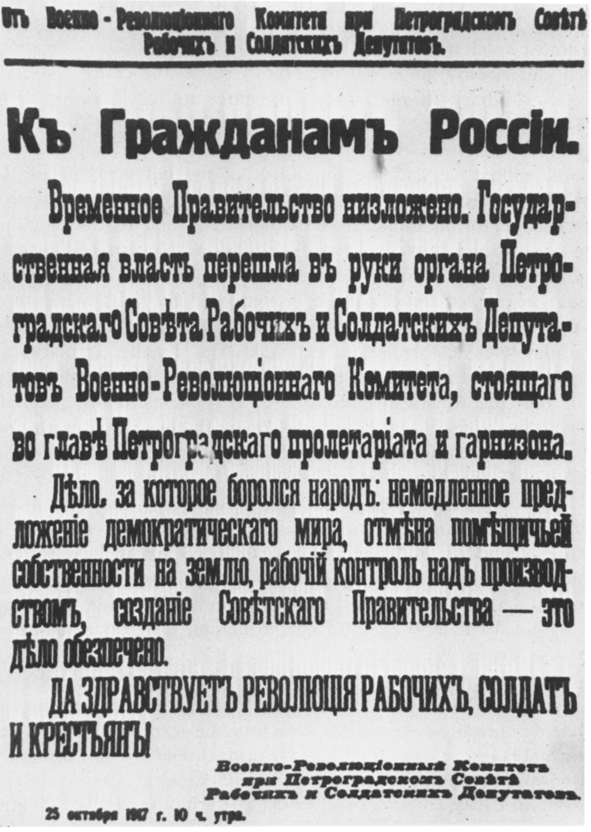

Even as these preparations for the seizure of the last bastions of the Provisional Government in Petrograd were being completed, Lenin, elsewhere at Smolny, was nervously watching the clock, by all indications most anxious to insure that the Kerensky regime would be totally eliminated before the start of the Congress of Soviets, now just a scant few hours away. At about 10:00 A.M. he drafted a manifesto “To the Citizens of Russia,” proclaiming the transfer of political power from the Kerensky government to the Military Revolutionary Committee:

25 October 1917

To the Citizens of Russia!

The Provisional Government has been overthrown. State power has passed into the hands of the organ of the Petrograd Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies, the Military Revolutionary Committee, which stands at the head of the Petrograd proletariat and garrison.

The cause for which the people have struggled—the immediate proposal of a democratic peace, the elimination of landlord estates, workers’ control over production, the creation of a soviet government—the triumph of this cause has been assured.

Long live the workers’, soldiers’, and peasants’ revolution!

The Military Revolutionary Committee of the Petrograd Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies5

Lenin’s manifesto of October 25, 1917, “To the Citizens of Russia,” proclaiming the transfer of political power from the Kerensky government to the Military Revolutionary Committee.

The seminal importance Lenin attached to congress delegates being faced, from the very start, with a fait accompli as regards the creation of a soviet government is clearly illustrated by the fact that this proclamation was printed and already going out over the wires to the entire country even before the Military Revolutionary Committee strategy meeting described above had ended.

If October 25 began as a day of energetic activity and hope for the left, the same cannot be said for supporters of the old government. In the Winter Palace, Kerensky by now had completed arrangements to meet troops heading for the capital from the northern front. A striking indication of the isolation and helplessness of the Provisional Government at this point is the fact that the Military Revolutionary Committee’s control of all rail terminals precluded travel outside of Petrograd by train, while for some time the General Staff was unable to provide the prime minister with even one automobile suitable for an extended trip. Finally, military officials managed to round up an open Pierce Arrow and a Renault, the latter borrowed from the American embassy. At 11:00 A.M., almost precisely the moment when Lenin’s manifesto proclaiming the overthrow of the government began circulating, the Renault, flying an American flag, tailed by the aristocratic Pierce Arrow, roared through the main arch of the General Staff building, barreled past Military Revolutionary Committee pickets already forming around the Winter Palace, and sped southwest ward out of the capital. Huddled in the back seat of the Pierce Arrow were the assistant to the commander of the Petrograd Military District, Kuzmin; two staff officers; and a pale and haggard Kerensky, on his way to begin a desperate hunt for loyal troops from the front, a mission that was to end in abject failure less than a week later.6

As Kerensky’s entourage streaked by the Mariinsky Palace, the relatively few deputies to the Preparliament assembled there were exchanging news of the latest political developments, awaiting the start of the day’s session. Within an hour, a large contingent of armed soldiers and sailors, under Chudnovsky’s command, began sealing off adjacent streets and posting guards at all palace entrances and exits. The armored car Oleg, flying a red flag, clattered up and took a position at the western corner of the palace.

When these preparations were completed, an unidentified Military Revolutionary Committee commissar entered the palace, searched out Avksentiev, and handed him a directive from the Military Revolutionary Committee ordering that the Mariinsky Palace be cleared without delay. Meanwhile, some soldiers and sailors burst into the building, brandishing their rifles, and posted themselves along the palace’s grand main staircase. While many of the frightened deputies dashed for their coats and prepared to brave the phalanx of armed soldiers and sailors, Avksentiev had the presence of mind to collect part of the Preparliament steering committee. These deputies hurriedly agreed to formally protest the Military Revolutionary Committee’s attack, but to make no attempt to resist it. They also instructed Avksentiev to reconvene the Preparliament at the earliest practicable moment. Before they were permitted to leave the palace, the identity of each of the deputies was carefully checked, but no one was detained. For the time being, the Military Revolutionary Committee forces were apparently under instructions to limit arrests to members of the government.7

Elsewhere by this time, insurgent ranks had been bolstered by the liberation from the Crosses Prison of the remaining Bolsheviks imprisoned there since the July days. A Military Revolutionary Committee commissar simply appeared at the ancient prison on the morning of October 25 with a small detachment of Red Guards and an order for the release of all political prisoners; among others, the Bolsheviks Semion Roshal, Sakharov, Tol-kachev, and Khaustov were immediately set free.8 At 2:00 P.M. the forces at the disposal of the Military Revolutionary Committee were increased still further by the arrival of the armada from Kronstadt. One of the more than a thousand sailors crammed on the deck of the Amur, I. Pavlov, subsequently recalled the waters outside Petrograd at midday, October 25:

What did the Gulf of Finland around Kronstadt and Petrograd look like then? This is conveyed well by a song that was popular at the time [sung to the melody of the familiar folk tune Stenka Razin]: “Iz za ostrova Kron-shtadta na prostor reki Nevy, vyplyvaiut mnogo lodok, v nikh sidiat bol’sheviki!” [From the island of Kronstadt toward the River Neva broad, there are many boats a-sailing—they have Bolsheviks on board.] If these words do not describe the Gulf of Finland exactly, it’s only because “boats” are mentioned. Substitute contemporary ships and you will have a fully accurate picture of the Gulf of Finland a few hours before the October battle.9

At the entrance to the harbor canal the Zaria svobody, pulled by the four tugs, dropped anchor; a detachment of sailors swarmed ashore and undertook to occupy the Baltic rail line between Ligovo and Oranienbaum. As the rest of the ships inched through the narrow channel, it occurred to Flerovsky, aboard the Amur, that if the government had had the foresight to lay a couple of mines and emplace even a dozen machine guns behind the parapet of the canal embankment, the carefully laid plans of the Kronstadters would have been wrecked. He heaved a sigh of relief as the motley assortment of ships passed through the canal unhindered and entered the Neva, where they were greeted by enthusiastic cheers from crowds of workers gathered on the banks. Flerovsky himself was in the cabin of the Amur ship’s committee below decks, discussing where to cast anchor, when a mighty, jubilant hurrah rent the air. Flerovsky ran up on deck just in time to see the Aurora execute a turn in the middle of the river, angling for a better view of the Winter Palace.10

As the men on the Aurora and the ships from Kronstadt spotted each other, cheers and shouts of greeting rang out, the round caps of the sailors filled the sky, and the Aurora’s band broke into a triumphant march. The Amur dropped anchor close by the Aurora, while some of the smaller boats continued on as far as the Admiralty. Moments later Antonov-Ovseenko went out to the Amur to give instructions to leaders of the Kronstadt detachment. Then, as students and professors at St. Petersburg University gawked from classroom windows on the embankment, the sailors, totaling around three thousand, disembarked, large numbers of them to join the forces preparing to besiege the Winter Palace. A member of this contingent later remembered that upon encountering garrison soldiers, some of the sailors berated them for their cowardliness during the July days. He recalled with satisfaction that the soldiers were now ready to repent their errors.11

Important developments were occurring in the meantime at Smolny. The great main hall there was packed to the rafters with Petrograd Soviet deputies and representatives from provincial soviets anxious for news of the latest events when Trotsky opened an emergency session of the Petrograd Soviet at 2:35 P.M.12 The fundamental transformation in the party’s tactics that had occurred during the night became apparent from the outset of this meeting, perhaps the most momentous in the history of the Petrograd Soviet. It will be recalled that less than twenty-four hours earlier, at another session of the Petrograd Soviet, Trotsky had insisted that an armed conflict “today or tomorrow, on the eve of the congress, is not in our plans.” Now, stepping up to the speaker’s platform, he immediately pronounced the Provisional Government’s obituary. “On behalf of the Military Revolutionary Committee,” he shouted, “I declare that the Provisional Government no longer exists!” To a storm of applause and shouts of “Long live the Military Revolutionary Committee!” he announced, in rapid order, that the Preparliament had been dispersed, that individual government ministers had been arrested, and that the rail stations, the post office, the central telegraph, the Petrograd Telegraph Agency, and the state bank had been occupied by forces of the Military Revolutionary Committee. “The Winter Palace has not been taken,” he reported, “but its fate will be decided momentarily. . . . In the history of the revolutionary movement I know of no other examples in which such huge masses were involved and which developed so bloodlessly. The power of the Provisional Government, headed by Kerensky, was dead and awaited the blow of the broom of history which had to sweep it away. . . . The population slept peacefully and did not know that at this time one power was replaced by another.”

In the midst of Trotsky’s speech, Lenin appeared in the hall. Catching sight of him, the audience rose to its feet, delivering a thundering ovation. With the greeting, “Long live Comrade Lenin, back with us again,” Trotsky turned the platform over to his comrade. Side by side, Lenin and Trotsky acknowledged the cheers of the crowd. “Comrades!” declared Lenin, over the din:

The workers’ and peasants’ revolution, the necessity of which has been talked about continuously by the Bolsheviks, has occurred. What is the significance of this workers’ and peasants’ revolution? First of all, the significance of this revolution is that we shall have a soviet government, our own organ of power without the participation of any bourgeois. The oppressed masses will form a government themselves. . . . This is the beginning of a new period in the history of Russia; and the present, third Russian revolution must ultimately lead to the victory of socialism. One of our immediate tasks is the necessity of ending the war at once.

We shall win the confidence of the peasantry by one decree, which will abolish landlord estates. The peasants will understand that their only salvation lies in an alliance with the workers. We will institute real workers’ control over production.

You have now learned how to work together in harmony, as evidenced by the revolution that has just occurred. We now possess the strength of a mass organization, which will triumph over everything and which will lead the proletariat to world revolution.

In Russia we must now devote ourselves to the construction of a proletarian socialist state.

Long live the world socialist revolution.

Lenin’s remarks were brief; yet it is perhaps not surprising that on this occasion most of his listeners did not trouble themselves with the question of how a workers’ government would survive in backward Russia and a hostile world. After Lenin’s remarks, Trotsky proposed that special commissars be dispatched to the front and throughout the country at once to inform the broad masses everywhere of the successful uprising in Petrograd. At this someone shouted, “You are anticipating the will of the Second Congress of Soviets,” to which Trotsky immediately retorted: “The will of the Second Congress of Soviets has already been predetermined by the fact of the workers’ and soldiers’ uprising. Now we have only to develop this triumph.”

The relatively few Mensheviks in attendance formally absolved themselves of responsibility for what they called “the tragic consequences of the conspiracy underway” and withdrew from the executive organs of the Petrograd Soviet. But most of the audience listened patiently to greetings by Lunacharsky and Zinoviev, the latter, like Lenin, making his first public appearance since July. The deputies shouted enthusiastic approval for a political statement drafted by Lenin and introduced by Volodarsky. Hailing the overthrow of the Provisional Government, the statement appealed to workers and soldiers everywhere to support the revolution; it also contained an expression of confidence that the Western European proletariat would help bring the cause of socialism to a full and stable victory.13 The deputies then dispersed, either to factories and barracks to spread the glad tidings, or, like Sukhanov, to grab a bite to eat before the opening session of the All-Russian Congress.

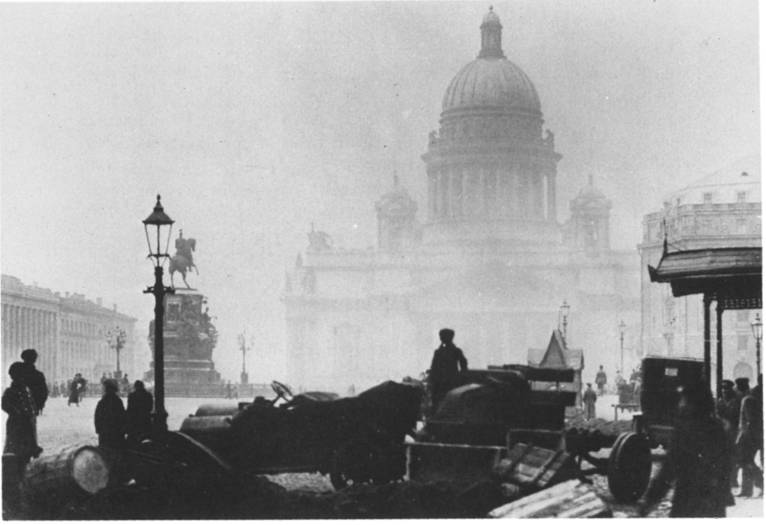

Barricades near St. Isaac’s Cathedral on October 25.

Dusk was nearing, and the Winter Palace was still not in Bolshevik hands. As early as 1:00 P.M. a detachment of sailors commanded by Ivan Sladkov had occupied the Admiralty, a few steps from the Winter Palace, and arrested the naval high command. At the same time, elements of the Pavlovsky Regiment had occupied the area around the Winter Palace, bounded by Millionnaia, Moshkov, and Bolshaia Koniushennaia streets, and Nevsky Prospect from the Ekaterinsky Canal to the Moika. Pickets, manned with armored cars and anti-aircraft guns, were set up on bridges over the Ekaterinsky Canal and the Moika, and on Morskaia Street. Later in the afternoon, Red Guard detachments from the Petrograd District and the Vyborg side joined the Pavlovsky soldiers, and troops from the Keksgolmsky Regiment occupied the area north of the Moika to the Admiralty, closing the ring of insurrectionary forces around the Palace Square. “The Provisional Government,” Dashkevich would subsequently recall, “was as good as in a mousetrap.”14

Noon had been the original deadline for the seizure of the Winter Palace. This was subsequently postponed to 3:00 and then 6:00 P.M., after which, to quote Podvoisky, the Military Revolutionary Committee “no longer bothered to set deadlines.”15 The agreed-upon ultimatum to the governmerit was not dispatched; instead, loyalist forces gained time to strengthen their defenses. Thus in the late afternoon, insurgent troops watched impatiently while cadets on the Palace Square erected massive barricades and machine gun emplacements of firewood brought from the General Staff building.

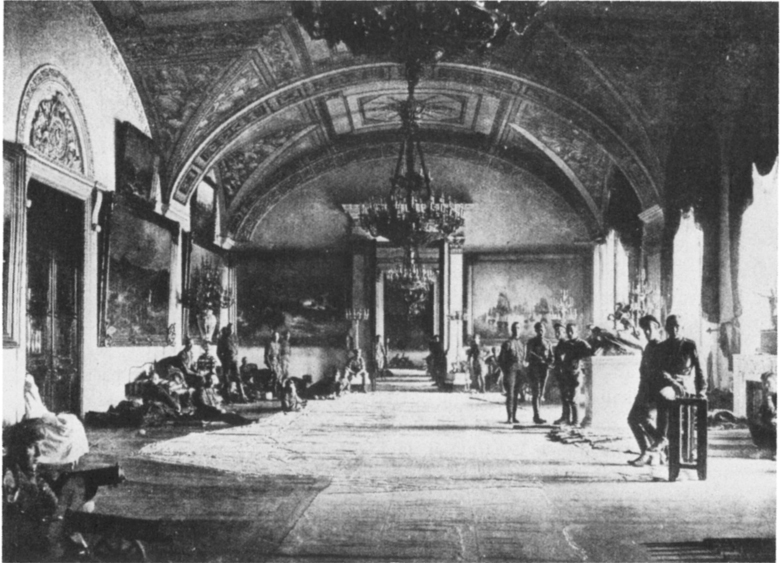

Petrograd during the October days. Baltic sailors helping to unpack artillery shells.

By 6:00 P.M. it was dark, drizzly, and cold, and many of the soldiers deployed in the area around the palace hours earlier were growing hungry and restless. Occasionally, one of them would lose patience and open fire at the cadets, only to be rebuked with the stern command, “Comrades, don’t shoot without orders.” On the Petrograd side, the Bolshevik Military Organization leader Tarasov-Rodionov, for one, was beside himself worrying about what was happening in the center of the city. “I had the urge,” he later wrote, “to drop everything—to rush to them [the Military Revolutionary Committee] to speed up this idiotically prolonged assault on the Winter Palace.” During these hours, Lenin sent Podvoisky, Antonov, and Chudnovsky dozens of notes in which he fumed that their procrastination was delaying the opening of the congress and needlessly stimulating anxiety among congress deputies.16

Antonov implies in his memoirs that unexpected delays in the mobilization of insurgent soldiers, faulty organization, and other problems of a minor yet troublesome nature were the main reasons it took so long to launch the culminating offensive on the government.17 In support of this view, there are indications that, for one reason or another, last-minute snags developed in connection with mobilizing some elements of the Preobrazhensky and Semenovsky regiments for the attack. More important, most of the sailor detachments from Helsingfors that the Military Revolutionary Committee was counting on for its assault did not arrive until late evening or even the following day. (In one case, a trainload of armed sailors was delayed in an open field outside Vyborg for many hours after the locomotive had burst its pipes; the Vyborg stationmaster, sympathetic to the government, had purposely provided the sailors with the least reliable locomotive available.18)

The Military Revolutionary Committee did indeed encounter a number of minor difficulties which prompted concern at the time, but which in retrospect appear almost comical. When Blagonravov began checking out the cannon at the Peter and Paul Fortress in preparation for shelling the Winter Palace, he found that the six-inch guns on the walls of the fortress facing the palace had not been used or cleaned for months. Artillery officers persuaded him that they were not serviceable. Blagonravov then made soldiers in the fortress drag heavy three-inch training cannon some distance to where they could be brought into action, only to find that all of these weapons had parts missing or were genuinely defective. He also discovered that shells of the proper caliber were not immediately available. After the loss of considerable time, it was ascertained that making the six-inch guns work was not impossible after all.19 Even more bizarre, by prior arrangement a lighted red lantern hoisted to the top of the fortress flagpole was to signal the start of the final push against the Winter Palace, yet when the moment for action arrived, no red lantern could be found. Recalls Blagonravov, “After a long search a suitable lamp was located, but then it proved extremely difficult to fix it on the flagpole so it could be seen.”20

Podvoisky, in his later writings, tended to attribute continuing delays in mounting an attack on the Winter Palace to the Military Revolutionary Committee’s hope, for the most part realized, of avoiding a bloody battle. As Podvoisky later recalled: “Already assured of victory, we awaited the humiliating end of the Provisional Government. We strove to insure that it would surrender in the face of the revolutionary strength which we then enjoyed. We did not open artillery fire, giving our strongest weapon, the class struggle, an opportunity to operate within the walls of the palace.”21 This consideration appears to have had some validity as well. There was little food for the almost three thousand officers, cadets, cossacks, and women soldiers in the Winter Palace on October 25. In the early afternoon the ubiquitous American journalist John Reed somehow wangled his way into the palace, wandered through one of the rooms where these troops were billeted, and took note of the dismal surroundings: “On both sides of the parqueted floor lay rows of dirty mattresses and blankets, upon which occasional soldiers were stretched out; everywhere was a litter of cigarettebutts, bits of bread, cloth, and empty bottles with expensive French labels. More and more soldiers, with the red shoulder-straps of the Yunker-schools, moved about in a stale atmosphere of tobacco smoke and unwashed humanity. . . . The place was a huge barrack, and evidently had been for weeks, from the look of the floor and walls.”22

Military school cadets in the Winter Palace during the October days.

As time passed and promised provisions and reinforcements from the front did not arrive, the government defenders became more and more demoralized, a circumstance known to the attackers. At 6:15 P.M. a large contingent of cadets from the Mikhailovsky Artillery School departed, taking with them four of the six heavy guns in the palace. Around 8:00 P.M. the two hundred cossacks on guard also returned to their barracks.

Representatives of the Military Revolutionary Committee participated in at least two attempts to convince other elements defending the government to leave peacefully. In the early evening, a representative of the Oranienbaum cadets persuaded Chudnovsky to accompany him to the palace to help arrange the peaceful withdrawal of his men. The cadets guaranteed Chudnovsky’s safe conduct and kept their word. But Petr Palchinsky, an engineer and deputy minister of trade and industry who was helping to direct the defense of the government, insisted that Chudnovsky be arrested. The cadets protested, however, and forced Chudnovsky’s release. Dashkevich had also slipped into the palace to try to win over some of the cadets; like Chudnovsky, he was detained and then allowed to leave. Partly as a result of the efforts of Chudnovsky and Dashkevich, more than half of the cadets guarding the Winter Palace left there at around 10:00 P.M.23

Whatever obstacles confronted the Military Revolutionary Committee in its assault on the Winter Palace on October 25 pale by comparison with the difficulties facing members of the Provisional Government, gathered in the grand Malachite Hall on the second floor of the palace. Here Konovalov convened a cabinet session at noon, an hour after Kerensky’s hurried departure for the front. Present were all of the ministers except Kerensky and the minister of food supply, a distinguished economist, Sergei Prokopovich, who, having been temporarily detained by an insurgent patrol in the morning, was unable to reach the Winter Palace before it was completely sealed off in the afternoon. Fortunately for the historian, several of the participants in this ill-fated last meeting of Kerensky’s cabinet penned detailed recollections of their final hours together; these tortured accounts bear witness to the almost complete isolation of the Provisional Government at this time, and to the ministers’ resulting confusion and ever-increasing paralysis of will.24

Konovalov opened the meeting with a report on the political situation in the capital. He informed the ministers of the Military Revolutionary Committee’s virtually unhampered success the previous night, of Polkovnikov’s shattering early-morning status report, and of Kerensky’s decision to rush to the front. For the first time, the full impact of the Petrograd Military District command’s utter helplessness in dealing with the insurrection underway, and indeed of its inability even to furnish personal protection for the ministers, was felt by the cabinet as a whole. Responding to Konovalov’s assessment, Admiral Verderevsky, the naval minister, observed coldly: “I don’t know why this session was called. . . . We have no tangible military force and consequently are incapable of taking any action whatever.”25 He suggested it would have been wiser to have convened a joint session with the Preparliament, an idea that became moot moments later, when news was received of the latter’s dispersal. At the start of their deliberations, however, most of the ministers did not fully share Verderevsky’s pessimism. Tending, no doubt wishfully, to place most of the blame for the government’s plight on Polkovnikov, they agreed to replace him with a “dictator” who would be given unlimited power to restore order and resolved that the cabinet would remain in continuous session in the Winter Palace for the duration of the emergency.

With periodic interruptions while Konovalov attempted unsuccessfully to bring more cossacks to the Winter Palace grounds, and while other ministers received disjointed reports on late-breaking developments and issued frantic appeals for help over the few phones still in operation to contacts elsewhere in the capital and over the direct wire to the front, the cabinet spent the better part of the next two hours engaged in a disorganized, meandering discussion of possible candidates for the post of “dictator.” Ultimately, they displayed their insensitivity to the prevailing popular mood by settling on the minister of welfare, Kishkin. A physician by profession and a Muscovite, Kishkin had no prestige in Petrograd. Worst of all, he was a Kadet. Indeed, the selection of Kishkin was exactly the opposite of the more conciliatory course urged on Kerensky the preceding day by the Preparliament—a blatant provocation to democratic circles and an unexpected boon to the extreme left.

Kishkin formally assumed his new position as governor-general shortly after 4:00 P.M. After naming as his assistants Palchinsky and Petr Rutenberg, an assistant to the commander of the Petrograd Military District, he rushed off to military headquarters to direct the struggle against the insurrection. There Kishkin immediately sacked Polkovnikov, replacing him with the chief of staff, General Bagratuni. As nearly as one can tell, the main effect of this reshuffling of personnel was to increase significantly the chaos reigning at headquarters. For in protest to the treatment accorded Polkovnikov, all of his closest associates, including the quartermaster, General Nikolai Paradelov, immediately resigned in a huff. Some of these individuals packed off and went home. Others simply stopped work; from time to time, they could be seen peering out of the windows of the General Staff building at the clusters of insurgent soldiers, sailors, and workers advancing along the banks of the Moika and up Millionnaia Street.26

Meanwhile, in the Winter Palace, the rest of the cabinet occupied itself in preparing an appeal for support to be printed up for mass circulation. At 6:15 P.M. the ministers were informed of the departure of the cadets from the Mikhailovsky Artillery School; fifteen minutes later, they adjourned to Kerensky’s third-floor private dining room, where a supper of borshch, fish, and artichokes—and more painful blows—awaited them.

By now, at the Peter and Paul Fortress, Blagonravov, under continual prodding from Smolny, had decided that the final stage of the attack on the government could be delayed no longer, this despite the fact that difficulties with the cannon and the signal lantern had not yet been fully surmounted. At 6:30 P.M. he dispatched two cyclists to the General Staff building, and in twenty minutes they arrived there armed with the following ultimatum:27

By order of the Military Revolutionary Committee of the Petrograd Soviet, the Provisional Government is declared overthrown. All power is transferred to the Petrograd Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies. The Winter Palace is surrounded by revolutionary forces. Cannon at the Peter and Paul Fortress and on the ships Aurora and Amur are aimed at the Winter Palace and the General Staff building. In the name of the Military Revolutionary Committee we propose that the Provisional Government and the troops loyal to it capitulate. . . . You have twenty minutes to answer. Your response should be given to our messenger. This ultimatum expires at 7:10, after which we will immediately open fire. . . .

Chairman of the Military Revolutionary Committee Antonov Commissar of the Peter and Paul Fortress G. B.

At the General Staff building when this message was delivered were, among others, Kishkin, General Bagratuni, General Paradelov, and Palchinsky and Rutenberg. They persuaded one of the cyclists to return to the fortress with a request for a ten-minute extension. Leaving Paradelov behind to receive the government’s response by phone and pass it on to the remaining cyclist, Kishkin, Bagratuni, and the others rushed to the Winter Palace to consult with the cabinet.28

Along with the news of the Military Revolutionary Committee’s ultimatum, the ministers also learned that large numbers of previously wavering cadets from Oranienbaum and Peterhof now intended to leave the palace. Besides, the original deadline set by Antonov was already close to expiration. The ministers hurried back to the Malachite Hall at once to consider the question of whether or not to surrender. Looking out at the crowded Neva and the Peter and Paul Fortress, one member of the cabinet wondered aloud, “What will happen to the palace if the Aurora opens fire?”

The cruiser Aurora on the Neva the night of October 25.

“It will be turned into a heap of ruins,” replied Admiral Verderevsky, adding sanguinely: “Her turrets are higher than the bridges. She can demolish the place without damaging any other building.”29

Still, all the ministers, including Verderevsky, were agreed that surrender in the prevailing circumstances was unthinkable. They resolved simply to ignore the ultimatum, and Kishkin, Gvozdev, and Konovalov immediately rushed off to coax the cadets to remain at their posts. In his diary, Minister of Justice Pavel Maliantovich attempted to explain the cabinet’s decision. He suggested that although at this point the ministers had lost hope of holding out until the arrival of outside help, they believed strongly that legally the Provisional Government could hand over its authority only to the Constituent Assembly. They felt a solemn obligation to resist until the very last moment so that it would be clear beyond doubt that they had yielded only to absolutely overwhelming force. That moment had not yet come, Maliantovich affirmed, hence the cabinet’s decision to give no reply to the Military Revolutionary Committee and to continue resistance.30

Ironically, at precisely the moment that the Military Revolutionary Committee’s ultimatum was delivered to General Staff headquarters, General Cheremisov, in Pskov, was conferring on the direct wire with General Bagratuni. At the start of the communication, Cheremisov had asked for a report on the condition of the capital. Specifically, he inquired as to the whereabouts of the government, the status of the Winter Palace, whether order was being maintained in the city, and whether or not units dispatched from the front had reached Petrograd. Bagratuni was answering these questions, as best he could, when he was called away to receive the ultimatum. General Paradelov then got on the Petrograd end of the direct wire and passed on to Cheremisov his misgivings about Kishkin’s appointment and behavior, stating quite directly his belief that the Provisional Government was doomed. Cheremisov, in turn, requested Paradelov to call the Winter Palace to obtain more information about the situation there.31 Paradelov went off to do this but was interrupted by Bagratuni, just then leaving for the Winter Palace with the ultimatum. Paradelov was instructed to stand by to receive the government’s telephoned response. As Paradelov waited for the message from the Winter Palace, insurgent soldiers and workers suddenly flooded the building; resistance was impossible.32 Meanwhile, Cheremisov, still at the other end of the direct wire, inquired impatiently, “Where is Paradelov, and will he give me an answer soon?” In response, a military telegrapher barely managed to tap out: “We will find him. . . . The headquarters has been occupied by Military Revolutionary Committee forces. I am quitting work and getting out of here!”33

Word of the capture of the General Staff building reached General Bagratuni and the cabinet in the second-floor office of one of Kerensky’s assistants, facing the palace courtyard, to which they had moved from the more vulnerable Malachite Hall. Bagratuni responded to the loss of his staff and headquarters by tendering his resignation. Soon after departing the palace, he was pulled from a cab and arrested by an insurgent patrol.

For their part, the ministers now dispatched the following radio-telegram to the Russian people:

To All, All, All!

The Petrograd Soviet has declared the Provisional Government overthrown, and demands that power be yielded to it under threat of shelling the Winter Palace from cannon in the Peter and Paul Fortress and aboard the cruiser Aurora, anchored on the Neva. The government can yield power only to the Constituent Assembly; because of this we have decided not to surrender and to put ourselves under the protection of the people and the army. In this regard a telegram was sent to Stavka. Stavka answered with word that a detachment had been dispatched. Let the country and the people respond to the mad attempt of the Bolsheviks to stimulate an uprising in the rear of the fighting army.34

The ministers also managed to establish telephone contact with the mayor of Petrograd, Shreider, in the City Duma building. They informed him that the Winter Palace was about to be shelled from the Aurora and the Peter and Paul Fortress, and appealed to him to help mobilize support for the government. The previous day, deeply concerned by the actions of the Military Revolutionary Committee, the City Duma, in which the SRs and Kadets still had a majority, had dispatched a fact-finding mission to Smolny; subsequently, in spite of fierce opposition from its Bolshevik members, the Duma, like the Preparliament, had initiated steps to form a Committee of Public Safety to help maintain order in the city and to protect the population. Now, upon receipt of the Provisional Government’s appeal, Shreider immediately convened the City Duma in emergency session. Announcing at the outset that “in a few minutes the cannon will begin to thunder . . . [and] the Provisional Government of the Russian Republic will perish in the ruins of the Winter Palace,” he called upon the Duma to help the government by all means possible. Inasmuch as the deputies had no military forces at their disposal, they agreed to dispatch emissaries to the Aurora, to Smolny, and to the Winter Palace immediately in an effort to halt the siege of the Winter Palace and to mediate differences between the government and the Military Revolutionary Committee.35

Meanwhile, at the Peter and Paul Fortress, cannon and signal-lantern difficulties having been overcome at last, Blagonravov and Antonov were preparing to commence the shelling of the Winter Palace. One further delay occurred when they received what turned out to be an erroneous report, evidently sparked by the surrender of General Staff headquarters, that the Winter Palace had capitulated. Blagonravov and Antonov drove across the Neva to check out the rumor themselves. At 9:40 P.M. Blagonravov finally returned to the fortress and signaled the Aurora to open fire. The Aurora responded by firing one blank round from its bow gun. The blast of a cannon shooting blanks is significantly greater than if it were using combat ammunition, and the ear-splitting reverberations of the Aurora’s first shot were felt throughout the capital. The blast impelled gawking spectators lined up on the Neva embankments to flop to the ground and crawl away in panic, and it contributed to the further thinning out of military forces inside the Winter Palace. (Many cadets finally abandoned their posts at this point and were followed shortly afterward by a number of the women soldiers.) Contrary to legend and to Verderevsky’s prediction, the Aurora’s shot did no physical damage.

After the Aurora’s action the artillerists at the Peter and Paul Fortress allowed time for those forces who wished to do so to leave the palace. During this interim, the officer of the watch on the Amur spotted a string of lights at the mouth of the Neva and sounded the alarm: “Ships approaching!” As their silhouettes came into view, old deck hands on the Amur triumphantly identified the arriving vessels as the destroyers Samson and Zabiiaka, accompanied by some of the other ships from Helsingfors.36

At around 11:00 P.M. Blagonravov gave the order to commence shooting in earnest. Most of the shells subsequently fired exploded spectacularly but harmlessly over the Neva, but one shattered a cornice on the palace and another smashed a third-floor corner window, exploding just above the room in which the government was meeting. The blast unnerved the ministers and influenced at least a few of them to have second thoughts about the wisdom of further resistance. Meanwhile, from the walls of the Peter and Paul Fortress, Tarasov-Rodionov watched the spectacular fireworks, whose tremors momentarily drowned out the sound of the rifle and machine gun fire and the droning of lighted streetcars crawling single file across the Troitsky and Palace bridges, and wondered at the incredibility of it all, of “the workers’ soviet overthrowing the bourgeois government while the peaceful life of the city continued uninterrupted.”37

To City Duma deputies, it was by this time patently clear that their hopes of interceding between the Military Revolutionary Committee and the embattled ministers in the Winter Palace would not be realized. A Military Revolutionary Committee commissar refused to permit the representatives of the City Duma to go anywhere near the Aurora. The delegation sent to the Winter Palace was halted several times by the besiegers and, in the end, forced to scurry back to the City Duma building after being fired upon from upper-story windows of the Winter Palace. (“The cadets probably didn’t see our white flag,” a member of the delegation later said.) The City Duma emissaries who went to Smolny, Mayor Shreider among them, fared somewhat better. They managed to have a few minutes with Kamenev, who helped arrange for Molotov to accompany them to the Winter Palace. But this delegation, too, was unable to make it through the narrow strip of no man’s land which now separated the tight ring of insurrectionary forces from the barricades set up by defenders of the government.38

About the time the City Duma was informed of these setbacks it also received a bitter telephone message from Semion Maslov, the minister of agriculture, and a right SR. The call was taken by Naum Bykhovsky, also an SR, who immediately relayed Maslov’s words to a hushed Duma. “We here in the Winter Palace have been abandoned and left to ourselves,” declared Maslov, as quoted by Bykhovsky. “The democracy sent us into the Provisional Government; we didn’t want the appointments, but we went. Yet now, when tragedy has struck, when we are being shot, we are not supported by anyone. Of course we will die. But my final words will be: ‘Contempt and damnation to the democracy which knew how to appoint us but was unable to defend us!’ ”39

Bykhovsky at once proposed that the entire Duma march in a body to the Winter Palace “to die along with our representatives.” “Let our comrades know,” he proclaimed, “that we have not abandoned them, let them know we will die with them.” This idea struck a responsive chord with just about everyone, except the Bolsheviks. Reporters present noted that most deputies stood and cheered for several minutes. Before the proposal was actually voted upon, the City Duma received a request from a representative of the All-Russian Executive Committee of Peasant Soviets that the leadership of the peasant soviets be permitted to “go out and die with the Duma.” It also heard from the minister of food supply, Prokopovich, who tearfully pleaded to be allowed to join the procession to the Winter Palace, “so that he could at least share the fate of his comrades.” Not to be outdone, Countess Sofia Panina, a prominent Kadet, volunteered “to stand in front of the cannon,” adding that “the Bolsheviks can fire at the Provisional Government over our dead bodies.” The start of the march to the Winter Palace was delayed a bit because someone demanded a roll call vote on Bykhovsky’s motion. During the roll call, most of the deputies insisted on individually declaring their readiness to “die with the government,” before voting “Yes”—whereupon each Bolshevik solemnly proclaimed that he would “go to the Soviet,” before registering an emphatic “No!”40

While all this was going on, Lenin remained at Smolny, raging at every delay in the seizure of the Winter Palace and still anxious that the All-Russian Congress not get underway until the members of the Provisional Government were securely behind bars. Andrei Bubnov later recorded that “the night of October 25 . . . Ilich hurried with the capture of the Winter Palace, putting extreme pressure on everyone and everybody when there was no news of how the attack was going.”41 Similarly, Podvoisky later remembered that Lenin now “paced around a small room at Smolny like a lion in a cage. He needed the Winter Palace at any cost: it remained the last gate on the road to workers’ power. V. I. scolded . . . he screamed . . . he was ready to shoot us.”42

Still, the start of the congress had been scheduled for 2:00 P.M. By late evening, the delegates had been milling around for hours; it was impossible to hold them back much longer, regardless of Lenin’s predilections. Finally, at 10:40 P.M., Dan rang the chairman’s bell, formally calling the congress into session. “The Central Executive Committee considers our customary opening political address superfluous,” he announced at the outset. “Even now, our comrades who are selflessly fulfilling the obligations we placed on them are under fire at the Winter Palace.”43

John Reed, who had pushed his way through a clamorous mob at the door of the hall, subsequently described the scene in Smolny’s white assembly hall as the congress opened:

In the rows of seats, under the white chandeliers, packed immovably in the aisles and on the sides, perched on every windowsill, and even the edge of the platform, the representatives of the workers and soldiers of all Russia awaited in anxious silence or wild exultation the ringing of the chairman’s bell. There was no heat in the hall but the stifling heat of unwashed human bodies. A foul blue cloud of cigarette smoke rose from the mass and hung in the thick air. Occasionally someone in authority mounted the tribune and asked the comrades not to smoke; then everybody, smokers and all, took up the cry “Don’t smoke, comrades!” and went on smoking. . . .

On the platform sat the leaders of the old Tsay-ee-kah [Central Executive Committee] . . . Dan was ringing the bell. Silence fell sharply intense, broken by the scuffling and disputing of the people at the door. . . .44

According to a preliminary report by the Credentials Committee, 300 of the 670 delegates assembled in Petrograd for the congress were Bolsheviks, 193 were SRs (of whom more than half were Left SRs), 68 were Mensheviks, 14 were Menshevik-Internationalists, and the remainder either were affiliated with one of a number of smaller political groups or did not belong to any formal organization.45 The dramatic rise in support for the Bolsheviks that had occurred in the previous several months was reflected in the fact that the party’s fraction was three times greater than it had been at the First All-Russian Congress of Soviets in June; the Bolsheviks were now far and away the largest single party represented at the congress. Yet it is essential to bear in mind that, despite this success, at the opening of the congress the Bolsheviks did not have an absolute majority without significant help from the Left SRs.

Because delegates, upon arrival at Smolny, were asked to fill out detailed personal questionnaires, we can ascertain not only the political affiliation of most of them, but also the character of each of the 402 local soviets represented at the congress and its official position on the construction of a new national government. Tabulation of these questionnaires reveals the striking fact that an overwhelming number of delegates, some 505 of them, came to Petrograd committed in principle to supporting the transfer of “all power to the soviets,” that is, the creation of a soviet government presumably reflective of the party composition of the congress. Eighty-six delegates were loosely bound to vote for “all power to the democracy,” meaning a homogeneous democratic government including representatives of peasant soviets, trade unions, cooperatives, etc., while twenty-one delegates were committed to support of a coalition democratic government in which some propertied elements, but not the Kadets, would be represented. Only fifty-five delegates, that is, significantly less than 10 percent, represented constituencies still favoring continuation of the Soviet’s former policy of coalition with the Kadets.46

As a result of the breakdown in relative voting strength, moments after the congress opened fourteen Bolsheviks took seats in the congress Presidium alongside seven Left SRs (the Mensheviks, allotted three seats in the Presidium, declined to fill them; the Menshevik-Internationalists did not fill the one seat allotted to them but reserved the right to do so). Dan, Lieber, Broido, Gots, Bogdanov, and Vasilii Filipovsky, who had directed the work of the Soviet since March, now vacated the seats at the head of the hall reserved for the top Soviet leadership; amid thunderous applause their places were immediately occupied by Trotsky, Kollontai, Lunacharsky, Nogin, Zinoviev, Kamkov, Maria Spiridonova, Mstislavsky, and other prominent Bolsheviks and Left SRs.47

As if punctuating this momentous changeover, an ominous sound was heard in the distance—the deep, pounding boom of exploding cannon. Rising to make an emergency announcement, Martov, in a shrill, trembling voice, demanded that, before anything else, the congress agree to seek a peaceful solution to the existing political crisis; in his view, the only way out of the emergency was first to stop the fighting and then to start negotiations for the creation of a united, democratic government acceptable to the entire democracy. With this in mind, he recommended selection of a special delegation to initiate discussions with other political parties and organizations aimed at bringing to an immediate end the clash which had erupted in the streets.

Speaking for the Left SRs, Mstislavsky immediately endorsed Martov’s proposal; more significantly, it was also apparently well received by many Bolsheviks. Glancing around the hall, Sukhanov, for one, noted that “Martov’s speech was greeted with a tumult of applause from a very large section of the meeting.” Observed a Delo naroda reporter, “Martov’s appeal was showered with torrents of applause by a majority in the hall.” Bearing in mind that most of the congress delegates had mandates to support the creation by the congress of a coalition government of parties represented in the Soviet and since Martov’s motion was directed toward that very end, there is no reason to doubt these observations. The published congress proceedings indicate that, on behalf of the Bolsheviks, Lunacharsky responded to Martov’s speech with the declaration that “the Bolshevik fraction has absolutely nothing against the proposal made by Martov.” The congress documents indicate as well that Martov’s proposal was quickly passed by unanimous vote.48

No sooner had the congress endorsed the creation of a democratic coalition government by negotiation, however, than a succession of speakers, all representatives of the formerly dominant moderate socialist bloc, rose to denounce the Bolsheviks. These speakers declared their intention of immediately walking out of the congress as a means of protesting and opposing the actions of the Bolsheviks. The first to express himself in this vein was Iakov Kharash, a Menshevik army officer and delegate from the Twelfth Army Committee. Proclaimed Kharash: “A criminal political venture has been going on behind the back of the All-Russian Congress, thanks to the political hypocrisy of the Bolshevik Party. The Mensheviks and SRs consider it necessary to disassociate themselves from everything that is going on here and to mobilize the public for defense against attempts to seize power.” Added Georgii Kuchin, also an officer and prominent Menshevik, speaking for a bloc of moderately inclined delegates from army committees at the front: “The congress was called primarily to discuss the question of forming a new government, and yet what do we see? We find that an irresponsible seizure of power has already occurred and that the will of the congress has been decided beforehand. . . . We must save the revolution from this mad venture. In the cause of rescuing the revolution we intend to mobilize all of the revolutionary elements in the army and the country. . . . [We] reject any responsibility for the consequences of this reckless venture and are withdrawing from this congress.”49

These blunt statements triggered a storm of protest and cries of “Kornilovites!” and “Who in the hell do you represent?” from a large portion of the assembled delegates. Yet after Kamenev restored a semblance of order, Lev Khinchuk, from the Moscow Soviet, and Mikhail Gendelman, a lawyer and member of the SR Central Committee, read similarly bitter and militantly hostile declarations on behalf of the Mensheviks and SRs respectively. “The only possible peaceful solution to the present crisis continues to lie in negotiations with the Provisional Government on the formation of a government representing all elements of the democracy,” Khinchuk insisted. At this, according to Sukhanov “a terrible din filled the hall; it was not only the Bolsheviks who were indignant, and for a long time the speaker wasn’t allowed to continue.” “We leave the present congress,” Khinchuk finally shouted, “and invite all other fractions similarly unwilling to accept responsibility for the actions of the Bolsheviks to assemble together to discuss the situation.” “Deserters,” came shouts from the hall. Echoed Gendelman: “Anticipating that an outburst of popular indignation will follow the inevitable discovery of the bankruptcy of Bolshevik promises . . . the Socialist Revolutionary fraction is calling upon the revolutionary forces of the country to organize themselves and to stand guard over the revolution. . . . Taking cognizance of the seizure of power by the Bolsheviks . . . , holding them fully responsible for the consequences of this insane and criminal action, and consequently finding it impossible to collaborate with them, the Socialist Revolutionary fraction is leaving the congress!”50

Tempers in the hall now skyrocketed; there erupted a fierce squall of footstamping, whistling, and cursing. In response to the uprising now openly proclaimed by the Military Revolutionary Committee, the Mensheviks and SRs had moved rightward, and the gulf separating them from the extreme left had suddenly grown wider than ever. When one recalls that less than twenty-four hours earlier the Menshevik and SR congress fractions, uniting broad segments of both parties, appeared on the verge of at long last breaking with the bourgeois parties and endorsing the creation of a homogeneous socialist government pledged to a program of peace and reform, the profound impact of the events of October 24–25 becomes clear. One can certainly understand why the Mensheviks and SRs reacted as they did. At the same time, it is difficult to escape the conclusion that by totally repudiating the actions of the Bolsheviks and of the workers and soldiers who willingly followed them, and, even more, by pulling out of the congress, the moderate socialists undercut efforts at compromise by the Menshevik-Internationalists, the Left SRs, and the Bolshevik moderates. In so doing, they played directly into Lenin’s hands, abruptly paving the way for the creation of a government which had never been publicly broached before—that is, an exclusively Bolshevik regime. In his memoir-history of the revolution, Sukhanov acknowledged the potentially immense historical significance of the Menshevik-SR walkout. He wrote that in leaving the congress “we completely untied the Bolsheviks’ hands, making them masters of the entire situation and yielding to them the whole arena of the revolution. A struggle at the congress for a united democratic front might have had some success. . . . By quitting the congress, we ourselves gave the Bolsheviks a monopoly of the Soviet, of the masses, and of the revolution. By our own irrational decision, we ensured the victory of Lenin’s whole line’!”51

All this is doubtless more apparent in retrospect than it was at the time. At any rate, following the declarations of Kharash, Kuchin, Khinchuk, and Gendelman, several radically inclined soldier-delegates took the floor to assert that the views of Kharash and Kuchin in no way represented the thinking of the average soldier. “Let them go—the army is not with them,” burst out a young, lean-faced soldier named Karl Peterson, representing the Latvian Rifle Regiment; his observation would soon be only too evident to all. At this the hall rocked with wild cheering. “Kuchin refers to the mobilization of forces,” shouted Frants Gzhelshchak, a Bolshevik soldier from the Second Army at the front, as soon as he could make himself heard. “Against whom—against the workers and soldiers who have come out to defend the revolution?” he asked. “Whom will he organize? Clearly not the workers and soldiers against whom he himself is determined to wage war.” Declared Fedor Lukianov, a soldier from the Third Army, also a Bolshevik, “The thinking of Kuchin is that of the top army organizations which we elected way back in April and which have long since failed to reflect the views and mood of the broad masses of the army.”52

At this point Genrikh Erlikh, a representative of the Bund (the Jewish social democratic organization), interrupted to inform the congress of the decision of a majority of City Duma deputies, taken moments earlier, to march en masse to the Winter Palace. Erlikh added that the Menshevik and SR fractions in the Executive Committee of the All-Russian Soviet of Peasant Deputies had decided to join the Duma deputies in protesting the application of violence against the Provisional Government, and invited all congress delegates “who did not wish a bloodbath” to participate in the march. It was at this point that the Mensheviks, SRs, Bundists, and members of the “front group”—deluged by shouts of “Deserters!” “Lackeys of the bourgeoisie!” and “Good riddance!”—rose from their places and made their way out of the hall.

Soon after the departure of the main bloc of Mensheviks and SRs, Martov, still intent most of all on facilitating a peaceful compromise between the moderate socialists and the radical left, took the floor to present a resolution on behalf of the Menshevik-Internationalists. His resolution condemned the Bolsheviks for organizing a coup d’état before the opening of the congress and called for creation of a broadly based democratic government to replace the Provisional Government. It read in part:

Taking into consideration that this coup d’état threatens to bring about bloodshed, civil war, and the triumph of a counterrevolution . . . [and] that the only way out of this situation which could still prevent the development of a civil war might be an agreement between insurgent elements and the rest of the democratic organizations on the formation of a democratic government which is recognized by the entire revolutionary democracy and to which the Provisional Government could painlessly surrender its power, the Menshevik [Internationalist] fraction proposes that the congress pass a resolution on the necessity of a peaceful settlement of the present crisis by the formation of an all-democratic government . . . that the congress appoint a delegation for the purpose of entering into negotiations with other democratic organs and all the socialist parties . . . [and] that it discontinue its work pending the disclosure of the results of this delegation’s efforts.53

It is easy to see that from Lenin’s point of view, passage of Martov’s resolution would have been a disaster; on the other hand, the departure of the moderates offered an opportunity which could now be exploited to consolidate the break with them. Not long after Martov resumed his seat, congress delegates rose and cheered the surprise appearance of the Bolshevik City Duma fraction, members of which, pushing their way into the crowded hall, announced that they had come “to triumph or die with the All-Russian Congress!” Then Trotsky, universally recognized as the Bolsheviks’ most forceful orator, took the platform to declare:

A rising of the masses of the people requires no justification. What has happened is an insurrection, and not a conspiracy. We hardened the revolutionary energy of the Petersburg workers and soldiers. We openly forged the will of the masses for an insurrection, and not a conspiracy. The masses of the people followed our banner and our insurrection was victorious. And now we are told: Renounce your victory, make concessions, compromise. With whom? I ask: With whom ought we to compromise? With those wretched groups who have left us or who are making this proposal? But after all we’ve had a full view of them. No one in Russia is with them any longer. A compromise is supposed to be made, as between two equal sides, by the millions of workers and peasants represented in this congress, whom they are ready, not for the first time or the last, to barter away as the bourgeoisie sees fit. No, here no compromise is possible. To those who have left and to those who tell us to do this we must say: You are miserable bankrupts, your role is played out; go where you ought to go: into the dustbin of history!

Amid stormy applause, Martov shouted in warning, “Then we’ll leave!” And Trotsky, without a pause, read a resolution condemning the departure of Menshevik and SR delegates from the congress as “a weak and treacherous attempt to break up the legally constituted all-Russian representative assembly of the worker and soldier masses at precisely the moment when their avant-garde, with arms in hand, is defending the congress and the revolution from the onslaught of the counterrevolution.” The resolution endorsed the insurrection against the Provisional Government and concluded: “The departure of the compromisers does not weaken the soviets. Inasmuch as it purges the worker and peasant revolution of counterrevolutionary influences, it strengthens them. Having listened to the declarations of the SRs and Mensheviks, the Second All-Russian Congress continues its work, the tasks of which have been predetermined by the will of the laboring people and their insurrection of October 24 and 25. Down with the compromisers! Down with the servants of the bourgeoisie! Long live the triumphant uprising of soldiers, workers, and peasants!”54

This bitter denunciation of the Mensheviks and SRs and blanket endorsement of the armed insurrection in Petrograd was, of course, as difficult for the Left SRs, left Mensheviks, and Bolshevik moderates to swallow as Martov’s resolution was for the Leninists. Kamkov, in a report to the First Left SR Congress in November, when these events were still very fresh in mind, attempted to explain the thinking of the Left SRs at this moment, when the gulf dividing Russian socialists widened, when in spite of Left SR efforts the Military Revolutionary Committee had been transformed into an insurrectionary organ and had overthrown the Provisional Government, and when the moderate socialists had repudiated and moved to combat this development:

As political leaders in a moment of decisive historical significance for the fate of not only the Russian but also the world revolution, we, least of all, could occupy ourselves with moralizing. As people concerned with the defense of the revolution we had first of all to ask ourselves what we should do today, when the uprising was a reality . . . and for us it was clear that for a revolutionary party in that phase of the Russian revolution that had developed . . . our place was with the revolution. . . . We decided not only to stay at Smolny but to play the most energetic role possible. . . . We believed we should direct all of our energies toward the creation of a new government, one which would be supported, if not by the entire revolutionary democracy, then at least by a majority of it. Despite the hostility engendered by the insurrection in Petrograd . . . knowing that included within the right was a large mass of honest revolutionaries who simply misunderstood the Russian revolution, we believed our task to be that of not contributing to exacerbating relations within the democracy. . . . We saw our task, the task of the Left SRs, as that of mending the broken links uniting the two fronts of the Russian democracy. . . . We were convinced that they [the moderates] would with some delay accept that platform which is not the platform of any one fraction or party, but the program of history, and that they would ultimately take part in the creation of a new government.55

At the Second Congress of Soviets session the night of October 25–26, loud cheers erupted when Kamkov, following Trotsky to the platform, made the ringing declaration: “The right SRs left the congress but we, the Left SRs, have stayed.” After the applause subsided, however, tactfully but forcefully, Kamkov spoke out against Trotsky’s course, arguing that the step Trotsky proposed was untimely “because counterrevolutionary efforts are continuing.” He added that the Bolsheviks did not have the support of the peasantry, “the infantry of the revolution without which the revolution would be destroyed.”56 With this in mind, he insisted that “the left ought not isolate itself from moderate democratic elements, but, to the contrary, should seek agreement with them.”

It is perhaps not without significance that the more temperate Lunacharsky, rather than Trotsky, rose to answer Kamkov:

Heavy tasks have fallen on us, of that there is no doubt. For the effective fulfillment of these tasks the unity of all the various genuinely revolutionary elements of the democracy is necessary. Kamkov’s criticism of us is unfounded. If starting this session we had initiated any steps whatever to reject or remove other elements, then Kamkov would be right. But all of us unanimously accepted Martov’s proposal to discuss peaceful ways of solving the crisis. And we were deluged by a hail of declarations. A systematic attack was conducted against us. . . . Without hearing us out, not even bothering to discuss their own proposal, they [the Mensheviks and SRs] immediately sought to fence themselves off from us. . . . In our resolution we simply wanted to say, precisely, honestly, and openly, that despite their treachery we will continue our efforts, we will lead the proletariat and the army to struggle and victory.57

The quarrel over the fundamentally differing views of Martov and Trotsky dragged on into the night. Finally, a representative of the Left SRs demanded a break for fractional discussions, threatening an immediate Left SR walkout if a recess were not called. The question was put to a vote and passed at 2:40 A.M., Kamenev warning that the congress would resume its deliberations in half an hour.58

By this time, the march of City Duma deputies to the Winter Palace had ended in a soggy fiasco. At around midnight Duma deputies, members of the Executive Committee of the Peasants’ Soviets, and deputies from the congress who had just walked out of Smolny (together numbering close to three hundred people), assembled outside the Duma building, on Nevsky Prospect, where a cold rain had now begun to fall. Led by Shreider and Prokopovich (the latter carrying an umbrella in one hand and a lantern in the other), marching four abreast and singing the “Marseillaise,” armed only with packages of bread and sausages “for the ministers,” the motley procession set out in the direction of the Admiralty. At the Kazan Square, less than a block away, the delegation was halted by a detachment of sailors and dissuaded from attempting to proceed further. John Reed, who was standing by, described the scene:

. . . Just at the corner of the Ekaterina Canal, under an arc-light, a cordon of armed sailors was drawn across the Nevsky, blocking the way to a crowd of people in column of fours. There were about three or four hundred of them, men in frock coats, well-dressed women, officers . . . and at the head white-bearded old Shreider, mayor of Petrograd, and Prokopovich, minister of supplies in the Provisional Government, arrested that morning and released. I caught sight of Malkin, reporter for the Russian Daily News. “Going to die in the Winter Palace,” he shouted cheerfully. The procession stood still, but from the front of it came loud argument. Shreider and Prokopovich were bellowing at the big sailor who seemed in command. “We demand to pass!” . . . “We can’t let you pass” [the sailor responded]. . . . Another sailor came up, very much irritated. “We will spank you!” he cried, energetically. “And if necessary we will shoot you too. Go home now, and leave us in peace!”

At this there was a great clamor of anger and resentment, Prokopovich had mounted some sort of box, and, waving his umbrella, he made a speech:

“Comrades and citizens!” he said. “Force is being used against us! We cannot have our innocent blood upon the hands of these ignorant men! . . . Let us return to the Duma and discuss the best means of saving the country and the Revolution!”

Whereupon, in dignified silence the procession marched around and back up the Nevsky, always in column of fours.59

It was now well after midnight, and the situation of the cabinet in the Winter Palace was growing more desperate by the minute. The steady dwindling of loyalist forces had by this time left portions of the east wing almost completely unprotected. Through windows in this section of the building, insurgents, in increasing numbers, were able to infiltrate the palace. In their second-floor meeting-room, many of the ministers now slouched spiritlessly in easy chairs or, like Maliantovich, stretched out on divans, awaiting the end. Konovalov, smoking one cigarette after another, nervously paced the room, disappearing next door from time to time to use the one phone still in service. The ministers could hear shouts, muffled explosions, and rifle and machine gun fire as the officers and cadets who had remained loyal to them fought futilely to fend off revolutionary forces. Their moments of greatest apprehension occurred when the artillery shell from the Peter and Paul Fortress burst in the room above and, somewhat later, when two grenades thrown by infiltrating sailors from an upper gallery exploded in a downstairs hall. Two cadets injured in the latter incident were carried to Kishkin for first aid.

Every so often Palchinsky popped in to try to calm the ministers, each time assuring them that the insurgents worming their way into the palace were being apprehended, and that the situation was still under control. Maliantovich recorded one of these moments: “Around one o’clock at night, or perhaps it was later, we learned that the procession from the Duma had set out. We let the guard know. . . . Again noise. . . . By this time we were accustomed to it. Most probably the Bolsheviks had broken into the palace once more, and, of course, had again been disarmed. . . . Palchinsky walked in. Of course, this was the case. Again they had let themselves be disarmed without resistance. Again, there were many of them. . . . How many of them are in the palace? Who is actually holding the palace now: we or the Bolsheviks?”60

Contrary to most accounts written in the Soviet Union, the Winter Palace was not captured by storm. Antonov himself subsequently recounted that by late evening “the attack on the palace had a completely disorganized character. . . . Finally, when we were able to ascertain that not many cadets remained, Chudnovsky and I led the attackers into the palace. By the time we entered, the cadets were offering no resistance.”61 This must have occurred at close to 2:00 A.M., for at that time Konovalov phoned Mayor Shreider to report: “The Military Revolutionary Committee has burst in. . . . All we have is a small force of cadets. . . . Our arrest is imminent.” Moments later, when Shreider called the Winter Palace back, a gruff voice replied: “What do you want? From where are you calling?”—to which Shreider responded, “I am calling from the city administration; what is going on there?” “I am the sentry,” answered the unfamiliar voice at the other end of the phone. “There is nothing going on here.”62

In the intervening moments, the sounds outside the room occupied by the Provisional Government had suddenly become more ominous. “A noise flared up and began to rise, spread, and draw nearer,” recalled Maliantovich. “Its varying sounds merged into one wave and at once something unusual, unlike the previous noises, resounded, something final. It was clear instantly that this was the end. . . . Those sitting or lying down jumped up and grabbed their overcoats. The tumult rose swiftly and its wave rolled up to us. . . . All this happened within a few minutes. From the entrance to the room of our guard came the shrill, excited shouts of a mass of voices, some single shots, the trampling of feet, thuds, shuffling, merging into one chaos of sounds and ever-mounting alarm.”63

Maliantovich adds that even then the small group of cadets outside the room where the ministers sat seemed ready to continue resistance; however, it was now apparent to everyone that “defense was useless and sacrifices aimless”—that the moment for surrender had finally arrived. Kishkin ordered the commander of the guard to announce the government’s readiness to yield. Then the ministers sat down around the table and watched numbly as the door was flung open and, as Maliantovich described it, “a little man flew into the room, like a chip tossed by a wave, under the pressure of the mob which poured in and spread at once, like water, filling all corners of the room.” The little man was Antonov. “The Provisional Government is here—what do you want?” Konovalov asked. “You are all under arrest,” Antonov replied, as Chudnovsky began taking down the names of the officials present and preparing a formal protocol. The realization that Kerensky, the prize they sought most of all, was not in the room, drove many of the attackers into a frenzy. “Bayonet all the sons of bitches on the spot!” someone yelled. Maliantovich records that it was Antonov who somehow managed to prevent the cabinet from being lynched, insisting firmly that “the members of the Provisional Government are under arrest. They will be confined to the Peter and Paul Fortress. I will not allow any violence against them.”64

The ministers were accompanied from the Winter Palace and through the Palace Square by a selected convoy of armed sailors and Red Guards and a swearing, mocking, fist-shaking mob. Because no cars were available, they were forced to travel to their place of detention on foot. As the procession neared the Troitsky Bridge, the crowd surrounding the ministers once again became ugly, demanding that they be beheaded and thrown into the Neva. This time, the members of the government were saved by the apparently random firing of a machine gun from an approaching car. At the sounds of the shots, machine gunners at the Peter and Paul Fortress, believing themselves under attack, also opened fire. Ministers, escorts, and onlookers scattered for cover. In the ensuing confusion, the prisoners were rushed across the bridge to the safety of the fortress.65

The ministers were led into a small garrison club-room, lighted only by a smoky kerosene lamp. At the front of the room they found Antonov, seated at a small table, completing the protocol which Chudnovsky had begun preparing at the Winter Palace. Antonov read the document aloud, calling the roll of arrested officials and inviting each to sign it. Thereupon, the ministers were led to dank cells in the ancient Trubetskoi Bastion not far from where former tsarist officials had been incarcerated since February. Along the way Konovalov suddenly realized he was without cigarettes. Gingerly, he asked the sailor accompanying him for one and was relieved when the sailor not only offered him shag and paper but, seeing his confusion about what to do with them, rolled him a smoke.66 Just before the door of his cell banged shut, Nikitin found in his pocket a half-forgotten telegram from the Ukrainian Rada to the Ministry of Interior. Handing it to Antonov, he observed matter of factly: “I received this yesterday—now it’s your problem.”67

At Smolny, meanwhile, the Congress of Soviets session had by now resumed. Ironically, it fell to Kamenev, who had fought tooth and nail against an insurrection for a month and a half, to announce the Provisional Government’s demise. “The leaders of the counterrevolution ensconced in the Winter Palace have been seized by the revolutionary garrison,” he barely managed to declare before complete pandemonium broke out in the hall. Kamenev went on to read the roll of former officials now incarcerated—at the mention of Tereshchenko, a name synonymous with the continuation of the hated war, the delegates erupted in wild shouts and applause once more.

As if to assure the congress that there was no immediate threat to the revolution, Kamenev also announced that the Third Cycle Battalion, called to Petrograd from the front by Kerensky, had come over to the side of the revolution. Shortly after this encouraging news, the Military Revolutionary Committee’s commissar from the garrison at Tsarskoe Selo rushed forward to declare that troops located there had pledged to protect the approaches to Petrograd. “Learning of the approach of the cyclists from the front,” he reported, “we prepared to rebuff them, but our concern proved unfounded since it turned out that among the comrade cyclists there were no enemies of the All-Russian Congress [the protocols record that this comment triggered another extended burst of enthusiastic applause]. When we sent our commissars to them it became clear that they also wanted the transfer of all power to the soviets, the immediate transfer of land to the peasants, and the institution of workers’ control over industry.”68

No sooner had the commissars from the Tsarskoe Selo garrison finished speaking than a representative of the Third Cycle Battalion itself demanded to be heard. He explained the attitude of his unit in these terms: