Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2018 with funding from Kahle/Austin Foundation

https://archive.org/details/easycompanysheepOOOOhowa

EASY COMPANY AND THE SUICIDE BOYS EASY COMPANY AND THE MEDICINE GUN EASY COMPANY AND THE GREEN ARROWS EASY COMPANY AND THE WHITE MAN’S PATH EASY COMPANY AND THE LONGHORNS EASY COMPANY AND THE BIG MEDICINE EASY COMPANY IN THE BLACK HILLS EASY COMPANY ON THE BITTER TRAIL EASY COMPANY IN COLTER’S HELL EASY COMPANY AND THE HEADLINE HUNTER EASY COMPANY AND THE ENGINEERS EASY COMPANY AND THE BLOODY FLAG EASY COMPANY ON THE OKLAHOMA TRAIL EASY COMPANY AND THE CHEROKEE BEAUTY EASY COMPANY AND THE BIG BLIZZARD EASY COMPANY AND THE LONG MARCHERS EASY COMPANY AND THE BOOTLEGGERS EASY COMPANY AND THE CARDSHARPS EASY COMPANY AND THE INDIAN DOCTOR EASY COMPANY AND THE TWILIGHT SNIPER

i i X ^ i' *

y K j

KEY

A. Parade and flagstaff

B. Officers’ quarters (“officers’ country”)

C. Enlisted men’s quarters: barracks, day room, and mess

D. Kitchen, quartermaster supplies, ordnance shop, guardhouse

E. Suttler’s store and other shops, tack room, and smithy

F. Stables

G. Quarters for dependents and guests; communal kitchen

H. Paddock

I. Road and telegraph line to regimental headquarters

J. Indian camp occupied by transient “friendlies”

INTERIOR

OUTSIDE

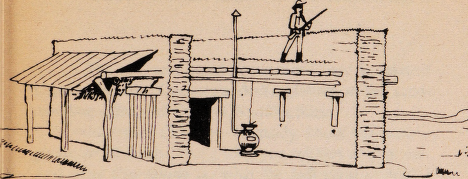

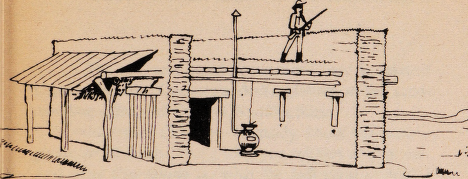

Outpost Number Nine is a typical High Plains military outpost of the days following the Battle of the Little Big Horn, and is the home of Easy Company. It is not a “fort”; an official fort is the headquarters of a regiment. However, it resembles a fort in its construction.

The birdseye view shows the general layout and orientation of Outpost Number Nine; features are explained in the Key.

The detail shows a cross-section through the outpost’s double walls, which ingeniously combine the functions of fortification and shelter.

The walls are constructed of sod, dug from the prairie on which Outpost Number Nine stands, and are sturdy enough to withstand an assault by anything less than artillery. The roof is of log beams covered by planking, tarpaper, and a top layer of sod. It also provides a parapet from which the outpost’s defenders can fire down on an attacking force.

The tall, weathered Texan stood hard in front of Captain Warner Conway’s desk, glaring at the commanding officer of Outpost Number Nine.

“Goddammit, Conway, I already know the army’s gonna do all it can. That’s what you soldiers always say. And what I’m saying is, what the hell good is that? I want you to do more than all you can!”

Warner Conway continued to look impassively at the redfaced, gravelly-voiced man standing before him, while out of the side of his eye he also took in First Lieutenant Matt Kincaid, standing across the room, and Elihu Cohoes’s foreman, Ching Domino, who thus far had remained silent.

“1 want protection for my herd, Conway, and I have got every right to expect that! Those thievin’ red sons of bitches butchered one of my prime steers, goddammit!”

“Maybe you’re lucky that’s all they did,” Conway said coolly, looking down at the back of his hand, and then bringing his eyes up to the cattleman’s, “since you were trespassing on tribal land to begin with.”

“What the hell do you mean!”

Conway got to his feet swiftly and crossed to the large wall map directly behind his two visitors. “Here.” He pointed with his index finger. “Here’s Horsehead Creek where you’re holding your herd now. That right?”

Cohoes reached into the pocket of his faded hickory shirt and took out a wooden match and put it between his lips. “Right.” He nodded, clipping off the word tightly, and began to chew on the match.

“And here”—Conway tapped a second area on the map with his middle finger—“here is where you say the Sioux killed your steer. Is that correct?”

Cohoes took a deep breath, his long nostrils flaring slightly. “That’s the size of it. What the hell you gettin’ at? They killed a steer, that’s right.”

Conway had turned back from the map and was facing the Texan squarely. Jerking his thumb over his shoulder, he said, “Horsehead Creek, where your herd is now, is on federal land.”

“I know that!”

“But where your steer was killed—”

“And butchered, goddammit!” interrupted Cohoes.

“—is on tribal land,” continued Conway, as though the cattleman had not spoken. “As I said, you were trespassing on tribal land.”

“That is the goddamnedest bullshit I ever heard! What the hell kind of army are you, anyways?” Cohoes’s fiery face whipped around to seek support from Ching Domino, but the foreman remained silent, a sneer curling his lip, his heavy eyes hooded as he stood loose, with his thumbs hooked into his heavy gunbelt.

Captain Warner Conway stood just as tall as the Texan. A man in his middle forties, distinguished, with graying hair at his temples, he was almost as lean and vigorous-looking as his adjutant and second-in-command, Matt Kincaid.

It was Kincaid who answered Cohoes now.

“We are here to protect everyone, Mr. Cohoes,” he said as Conway walked back to the swivel chair behind his desk and sat down. “But the United States Army does not play favorites. We favor the law. Easy Company will do all that’s necessary to protect your herd of cattle, but you must keep your beeves on federal land.”

Ignoring Kincaid, Cohoes glared at Conway. “I am

2

saying one thing to you, Conway, and it is this. If I, by Jesus, see or even smell one of them red sons of bitches near my beeves, I will wipe that whole fucking tribe off of the face of God’s green earth. So help me!”

Elihu Cohoes, known as a man not to be argued with, known all over the Panhandle as a man who didn’t give a good goddamn about anyone, stood there chewing on the wooden lucifer, switching it from one side of his mouth to the other, with his eyes hard on Easy Company’s CO. Now, hearing Kincaid move behind him, he canted his head at the lieutenant.

“Captain Conway and I have both heard you, mister,” Matt said, and his words were not warm. “And the captain has given you his reply.”

Cohoes glanced again at his foreman. Ching Domino was a man of average height with tight, olive-colored skin, closely spaced eyes, and, under his dirty black Stetson hat, shiny black hair. His clothes were tight on his body, looking. Matt thought, as though they’d been painted on him. He sure didn’t look like a cattleman, and Kincaid wondered what he was really doing with a man like Cohoes, who was all steer and leather and no question about his way of life.

Cohoes, seeing that his foreman was still not going to speak, and indeed realizing it wasn’t necessary, turned back to Conway, who was regarding him quietly.

Elihu Cohoes, a man of fifty-odd years, with a trail- hardened, leathery face and hands to match, looked as though that leather went all the way through. His nose was long, and he had the habit of rubbing it with his callused thumb—the way a horse will rub its nose along its extended foreleg, Conway thought as he watched now.

Blind in one eye, Cohoes generally turned his head slightly sideways when he spoke to someone. The mishap had occurred in a Fort Worth gambling establishment

3

when some frisky cow waddy had fired through one of the upstairs windows while racing his horse up and down that area known as the Cabbage Patch. It was pure chance that the bullet had streaked along the room occupant’s cheek and across his eye. Though Cohoes had lost half of his sight, he had never lost his anger. It took a while for Cohoes to find the miscreant, but when he did, the fellow took up permanent residence in Fort Worth—or, rather, under it.

Ching Domino was remembering it, as a matter of fact, as he watched Cohoes rub his nose, for the story was well known; and now in Conway’s office he began to ponder on how these damn fool soldier boys didn’t know who they were by-God dealing with.

Conway had placed the palms of his hands flat on his desk, and now, leaning forward a little, he looked at Elihu Cohoes dead-center. “Mr. Cohoes...” he began, and Matt Kincaid noted the patience purring in the captain’s voice. “Mr. Cohoes, I can only assure you for the last time that the army offers you full cooperation, to the extent of men and equipment available. Let me remind you once again that we are a single company of mounted infantry here at Outpost Number Nine, with an area to patrol that runs from the Bighorns to the South Pass; that includes the Absarokas and the High Plains. That is a whole lot of Wyoming, mister. And we are not only talking about a sizable territory, we are talking about the Sioux, the Cheyenne, and the Arapaho, not to mention a growing population of white settlers—all of whom want something from us.”

“Our scalps, more often than not,” Kincaid said. “I think Captain Conway is telling you that Easy Company will do all it can to protect your herd, but don’t expect miracles.” Kincaid had difficulty in not releasing a long sigh as he finished repeating simply what had been said at the very beginning.

Still, the Texan’s hard face darkened. “Captain, I am telling it to you and the lieutenant once more; I got two thousand head of prime longhorns out there at Horsehead, which I aim to fatten up on Greybull grass ’fore pushing ’em up to the Stinking Water for seed stock and for shipping.” He shifted his good eye over to Matt and then swung his gaze back to Conway.

“By God, I know men in Washington. You are not dealing with some half-assed sodbuster, sheep-dipper, or Injun lover. You are talkin’, by God, to a Texas cattleman, and I want more than them maybes and all that shit. I want an escort and full army cooperation when I trail up to the Stinking Water, and I want you to do something about them red bastards what killed and butchered that longhorn, and for which I am billin’ the army!”

Kincaid watched Conway’s ears turn red, a sure sign of displeasure; but the captain’s voice was as hard and even as a milled board.

“And Mr. Cohoes, I am telling you I will be listening to the other side on that matter—the Sioux. You will have your escort—provided I have men to spare—at the time you’re ready to push up to the Stinking Water River.”

The Texan, still exasperated, took his Stetson hat off his head and immediately put it back on again.

“What you figger, Ching?”

“That is a piss-poor effort at helpin’ honest white men.” It was the first he had spoken, and the words came out slow and heavy.

“My feelin’s exactly,” Cohoes said, with a hard nod of his head.

It seemed to Matt Kincaid that Conway’s Virginia accent was more apparent when he spoke now; he knew this to be the case whenever the captain was really controlling his anger. “I will give you one other assurance, Mr. Cohoes. The United States Army in the Wyoming

5

Territory is, and will be, impartial. We do not take sides; we see that the treaties with the Indians are honored, and we strive to maintain law and order, keeping the peace where it is at all possible. This means, sir, that you and your men will also obey the law. Just remember this— if there is any fighting with Indians to be done around here, it will be the army that does it. I trust that this is quite clear!” Captain Conway stood, the knuckles of his two hands just touching the top of his desk.

“Captain Conway, I will be expectin’ action on this, you better believe it.” And with a snort, with a nod toward Ching Domino, and with that lucifer still in his teeth, Elihu Cohoes tromped out of the office, his foreman following with the very same sneer on his face that had been there when he entered.

When the door had closed behind them, Conway released a long sigh and reached for his box of cigars.

“Well, sir, they still breed ’em tough down in the Panhandle,” Matt said with a wry grin.

The captain bit off the end of his cigar. “And cantankerous,” he added.

They were silent a moment.

“So what do you think, Matt?”

Kincaid moved to the chair indicated by the captain and sat down. “Two things, sir. First, a visit to the Brules, to see what Little Hawk has to say about that steer.”

Conway nodded, lighting his cigar. Waving out the match, he said, “And second—Horsehead Creek?”

“Yes, sir.”

“You’ll take a squad?”

“A squad, and Windy if he gets back.”

“Where is that lecherous old rascal?” asked Conway, his good humor returning with a rush.

Matt grinned. “Not at Tipi Town, for a change. He

6

is out scouting the prospects of game, and exercising his Delawares. He likes to keep those scouts sharp.”

“Damned lucky for us he does.” Conway released a cloud of smoke and, leaning back in his swivel chair, raised his eyes as the smoke floated toward the ceiling. “I am thinking about Ching Domino,” he said suddenly.

“Funny thing, sir, so was I.”

“I’ll wager our thoughts were the same,” Conway said, dropping his head down and looking directly at his second-in-command.

“If that boy is a cattle foreman...” Kincaid let it hang, opening his hands and shrugging.

“...then I’m a full-blooded Sioux,” Conway finished.

“I almost dropped when he finally said something. Captain, he is one mean-looking son of a bitch.”

“You are talking about his face, his body, and especially that tied-down Navy Colt that looks to have had plenty of use.”

“I don’t believe Ching Domino knows a cow from a jackrabbit, but I’ll bet my last dollar he can shoot the eye out of a striking snake.”

“Interesting, Cohoes wasn’t carrying any hardware.”

“A lot of cattlemen don’t, sir.”

Conway nodded. “I guess you don’t need to, if you can afford to hire somebody to carry it for you, and Cohoes can sure do that.”

Matt turned suddenly toward the window, listening. “It could be Windy, sir; he’s due.”

“Better have a look, then.”

Matt Kincaid stood up. In his thirties, he was tall, but not stringy like Cohoes. He was tall and broad-shouldered, and at the same time lithe, narrow at the hips, and ruggedly handsome. Conway looked admiringly at his adjutant. Kincaid, serving his second tour of frontier

7

duty, was the man Warner Conway depended upon more than any other. Like Conway, Kincaid had been passed by for promotion, and like the captain, he seldom mentioned the fact. Conway knew that without Matt Kincaid, Outpost Number Nine would be a whole lot poorer.

Now, as Matt opened the door of the orderly room, they both heard the sentry calling from the lookout tower.

Private Billy Golightly, walking guard along the perimeter fence, had watched the red dawn spreading across the sky, turning to gold as it touched the east wall of Outpost Number Nine, and washing over TipiTown, the little village of transient Indians that lay several hundred yards to the northeast. A jay called in the thin, chill morning air, and in the Indian village a dog began barking.

Billy Golightly, a raw recruit—no one seemed to know from where—was half dreaming of coffee and the pleasures of prone relaxation in his bunk when he was suddenly pulled right into the present as he heard hooves drumming toward the outpost. At that same moment, the picket guard called out.

“Two riders coming in! Windy Mandalian and a Delaware!”

Private Golightly had been well trained by his platoon sergeant, Gus Olsen, and by First Sergeant Ben Cohen. Quickly he brought his Springfield to port arms and headed for a stack of firewood that would afford him protection, should the report be a false one. Cohen and just about everyone else on the post had warned him how clever the hostiles were at calling out fake sentry reports or, during a skirmish, blowing false calls on a bugle, and sometimes even dressing up in soldiers’ uniforms, causing enormous confusion.

In a moment two riders broke into view, and Private

8

Golightly was relieved to see that the picket guard’s call had been true.

They were cantering in pretty fast; one on a blue roan, the other riding an Indian paint. The Delaware was sitting straight up on his pony’s blanket-clad back, his muscular legs gripping the animal’s flanks, his hands wrapped into its thick mane; his companion, on the roan, was dressed in fringed buckskin, and sat easy in a battered stock saddle. There was no mistaking them. It could only be Easy Company’s chief scout and one of his men.

The big gates were opened from the inside, and the riders trotted briskly in. Henry Walks Quickly, the young Delaware, jumped off his pony, while Windy Mandalian, although seeming to move in a more leisurely manner, was actually on the ground at the same time.

At just that moment. Matt Kincaid came out of the orderly room and strode across the parade toward the gate.

Henry Walks Quickly, the Delaware, looked impassively at the officer, waiting. Windy sniffed, and then ejected a stream of tobacco juice at a pile of fresh horse manure on the parade.

“You’re still in one piece,” Matt said as he looked at the long, lean scout and his companion.

“Still got our hair.” Windy’s grin was sour. “And the Sioux still got theirs.”

Matt turned to the Delaware. “You took good care of him, eh, Henry?”

The Delaware nodded. “We take good care,” he said. “Now we want coffee.”

“Go see Dutch in the mess hall.” Then, when one of the stable detail had taken the horses, Matt turned back to Windy. “We’ll go see the captain.” And on the way across the parade he filled the scout in on the meeting with Elihu Cohoes and his foreman.

9

Conway waved Kincaid to a chair, while Windy took up his customary position next to the window, declining a formal seat.

“Could stand a cup of the Dutchman’s jawbreaker,” the scout said.

“It’s on the way.” Conway leaned forward on his desk, a cigar between the thumb and first finger of his right hand. There was a question in his eyes, but he knew there was no way you could hurry words out of Windy Mandalian.

Fortunately, at that moment there was a knock at the door, and it was Corporal Bradshaw, the company clerk, with coffee for the three of them.

“That is what I call service,” Windy said with a grin.

Conway, studying him a moment, wondered whether he would take the plug of tobacco out of his mouth before drinking his coffee. He was relieved to see his chief scout lean forward and spit an enormous glob of tobacco and thick saliva into the cuspidor by his desk, right on target. The rank odor of chewed cut-plug wafted across the captain’s desk, and he reached for his cigar.

Windy sighed, addressing his cup of coffee. Standing by the window, his hawk nose, sharp jaw, and piercing eyes were emphasized by the morning light that shone through it. Mostly, the sunlight accentuated his amazing likeness to an Indian. There were some who knew him, however—especially among the Sioux, the Cheyenne, and the Arapaho—who claimed he was at least one- quarter coyote and one-quarter grizzly.

Matt told Conway, “I briefed Windy on our meeting with Cohoes.”

“Don’t need no filling in,” the scout said. “I know that type like the back of my hand. Coyote piss and buffalo shit from the feet up.” He took a gurgling pull at his coffee. “Not bad for gunpowder coffee,” he said.

10

“Got a bit of news. First, I seen them two riding off when I was coming in with Henry. The tall one, he is a cowman for sure, but the other, he sits that hoss like he had a spike up his ass. I’m talking about the one with the tied-down pistol, and the Winchester in his saddle boot. He is no good, that feller.”

“We know that,” Conway said. “Matt and I can’t figure what he’s doing punching cows.”

“I reckon he ain’t punched a single cow worth mention. He’s a regulator. Now the question is, gents, what does this feller Cohoes want with a gunhawk?” And he dropped one eyelid while keeping the other wide open. A grin began to spread across his face, raising his whiskers along the sides of his jaw. They sat for a moment in silence, each with his coffee and his own thoughts regarding Cohoes and Ching Domino and the Texas cattle. Now both officers watched as Windy Mandalian, having finished his coffee, took out his plug of tobacco and sliced off a sizable chew with his Bowie knife. The two men, familiar with his ways, waited patiently, for it was clear he had more to say; as usual he was saving the best for last.

The scout’s movements as he prepared his chew were deliberate—slow, sure, with nothing unnecessary to the accomplishment of his task. Both Conway and Kincaid knew that Windy could move with extraordinary speed when necessary, as any number of dead Indians might have testified.

The scout finally had his fresh chew working, moving it around in his jaws to work up flavor and consistency.

Conway had been watching him in fascination, as he often did, and now he said, “Well, if we can keep the Texans off Indian land, and the B rules off those fat cattle, we might avoid trouble. Matt’s going to pay Little Hawk a visit. Maybe you’d like to go along, Windy.”

The scout nodded. “Like to see that old boy again.

Me and him is old buddies.”

Conway was studying Mandalian closely, unable to understand how he could hold such an enormous chunk of tobacco in his mouth and speak halfway intelligibly at the same time. Windy looked as though he had an apple in his cheek.

The scout leaned forward all at once, with no warning, and let fly at the captain’s cuspidor. He missed.

“Shit. Well, mebbe I’m out of practice.” He stretched, then settled into his easy self again. “Tears to me, Captain Conway, we do have trouble coming up.”

“You mean that steer?” Matt asked.

“I do not. I mean somethin’ else.”

“Something else?” Conway said. “What else? Will you please tell us, for Christ’s sake?”

Windy shifted his chew to the other side of his mouth and looked again at the cuspidor, while Conway glared at him with impatience. But the scout was not perturbed. He spat with fair accuracy this time, and seemed pleased with himself, wiping his beard and sniffing.

Then he said one word. “Sheep.”

“Sheep?” Conway echoed.

Windy nodded. “What every cattleman loves.”

“Sheep, here?” Conway could hardly believe what he was hearing. “But this isn’t sheep country!”

“It might be about to be, Captain. There is a flock of about fifteen hundred woollies on its way down from the Absarokas. Should be around here in a day or two.”

“You mean they are actually headed for Number Nine?” Kincaid asked.

“Told ’em they better, if they want to find out how to keep their hair in this here country.” And Windy lowered both eyelids this time, then opened them real wide. “You know what’ll happen if the Brule get wind of ’em.

And I expect they know about them by now.”

“And when Cohoes and his bunch meet those sheep,” said Conway, “it’ll not be any social event.” And he shook his head.

“Those cattlemen and sheepmen might make the Indians seem kinda tame,” Windy observed. “’Specially when I tell you what sort of gentleman is ramrodding them woollies.”

Conway and Kincaid both stared at him in surprise. “You mean,” said Matt, “you met up with him?”

“I sure did.”

“What are you saying?” Conway demanded. “Who is bringing them in, and where are they coming from?”

“They’re from Nevada. Come across the mountains looking for new graze. They’re scouting. If they like the place, they’ll tell the folks back home, and we’ll see more sheep and sheepherders around here than flies on a bull’s ass, come summertime. This could be just the beginning.”

“Jesus,” Matt said softly. “We could be getting ourselves right in the middle of a range war.”

“And don’t forget the noble red man,” Windy said. “He will be after our ass too. We will be in the middle of a sweet threesome.”

A grim silence fell while Windy worked his chew.

Finally the scout said, “I didn’t get around to tellin’ you about the head sheepherder.”

“Who is he?”

“I can’t pemounce his name,” Windy said. “They call ’emselves Basques.”

“Basques!” said Conway.

“They explained it to me. They ain’t Spaniards, and i they ain’t French neither, though they come from a place between them two countries. But they been living in Nevada and growing woollies this good while. Still,

you’ll have a helluva time trying to understand then- language. Worse’n Sioux or any of them others.”

“It’s an old language,” Conway said. “Ancient.”

“I’ve heard it was older than Latin,” Matt said, “and a whole lot more difficult.”

“You mentioned their leader,” Conway said.

“Like I say, he’s got a name I can’t pemounce, but he looks to be somethin’ between a bull moose and a mountain lion; and I wouldn’t be surprised if there wasn’t a touch of rattlesnake there too.”

Windy paused, then said, “I have heard of those Basque fellers before. You don’t push ’em. They’re easygoing like this feller I’m telling you about; they like to sing and dance and drink and all that. But, well...”

“How many are they?”

“I counted twelve.” Windy sniffed, moving his chew to his other cheek. “They got Spencers. I seen this head feller handle that weapon. When I told him there was liable to be hostiles not appreciatin’ them sheep cornin’ into what they consider their country he took out a deck of cards and picked one and set it up a little ways away from us, ’bout from here to the sergeant’s desk out yonder.” Windy paused. “He set it up sideways. I was a mite impressed when he hit the edge of that card with his first shot.” He sniffed again and looked at the cuspidor, but didn’t let fly. Instead he said, “Only person I ever seed that could shoot that good is myself.”