![]()

With François Quesnay we introduce an odd group of French reformers who sought to rationalize the rickety economic system of France in the years before the French Revolution. Quesnay himself was physician to no less famous a personage than Mme. de Pompadour, mistress to His Majesty Louis XV. His small but prestigious circle included the renowned Marquis de Mirabeau, who had published Cantillon’s work in 1755; Anne Robert Jacques Turgot, Controleur Général des Finances under Louis XVI in 1774, whose remarkable work we shall meet in the next chapter; and du Pont de Nemours, a talented young scholar who eventually emigrated to America where he opened a gunpowder plant. Adam Smith would have dedicated The Wealth of Nations to Quesnay had not the doctor died before its publication.

Quesnay’s circle called its approach to political economy Physiocracy. The word means “order of nature,” and it refers to the central belief that land alone yields a surplus because nature labors with man, whereas man working with machines can do no more than reshape the material that had originally been wrested from the fecund soil. Strange as it sounds to modern ears, there is a prima facie rationale for this belief: Did not 100 bushels of wheat yield a crop of 300 or 400 bushels? Whence came these additional bushels if not from nature’s generosity?

Thus Quesnay and his followers called all agricultural work “productive,” because it seemed to yield a tangible surplus of wealth over the labor that was expended on it, whereas industrial work was more severely described as “sterile,” insofar as its products, however useful, did not evidence an unambiguous and tangible increase in wealth comparable to the contrast between the corn sowed and the corn reaped. Here is how Quesnay describes matters in his article “Men,” written for Diderot’s Encyclopedia.

_____________

EXTRACT FROM ‘MEN’

… Those who make manufactured commodities do not produce wealth, because their labour increases the value of commodities only by an amount equal to the wages which are paid to them and which are drawn from the product of landed property. The manufacturer who makes cloth, the tailor who makes clothes, the cobbler who makes shoes, do not produce wealth any more than do the cook who makes his master’s dinner, the worker who saws wood, or the musicians who give a concert. They are all paid out of one and the same fund, in proportion to the rate of reward fixed for their work, and they spend their receipts in order to obtain their subsistence. Thus they consume as much as they produce; the product of their labour is equal to the cost of their labour, and no surplus of wealth results from it. Thus it is only those who cause to be generated from landed property products whose value exceeds their costs who produce weath or annual revenue.11

_____________

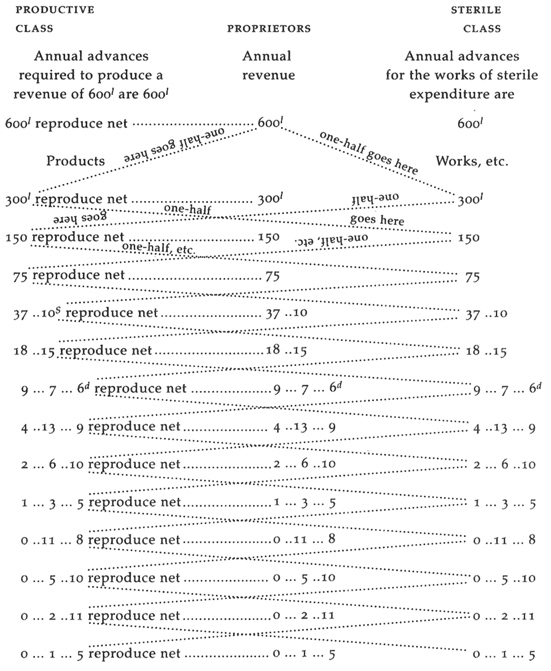

What is the fallacy in this analysis? We will come to that shortly. But first let us look at an unusually interesting aspect of Physiocracy which anticipates a direction in which economic analysis would be moving a hundred years later. This is its famous “zigzag” diagram (or Tableau Économique) which first appeared in Quesnay’s manuscript in 1758, and thereafter in many printed editions. Recall Cantillon’s comment that there seemed to be no “exact or geometrical” way of determining prices (see page 31). The Physiocratic zigzags do not illumine how prices are determined, but they illustrate something even more interesting—how a commercial society renews and replenishes itself. Let us therefore look at one of many zigzags, from Quesnay’s Third edition.12

One cannot actually read this bizarre diagram without benefit of the notes and explanations that Quesnay adds to the figure itself. Once we take these into account, however, we begin to see the rationale behind the presentation.

Let us begin with the three designations at the top: Productive class, Proprietors, and Sterile class. We should note that the first and last are not actually social classes, insofar as they include employers as well as workmen, and that the Proprietors include very large numbers of servants along with a much smaller number of seigneurs. Hence, the three columns are better thought of as “sectors.” Equally important is Quesnay’s allocation of population among these sectors, also not shown on the zigzag: the Productives number half the population, the Proprietors (including their large retinues) one quarter, and the Steriles comprise the last quarter.

Last, and emphatically not least, is an assumption about the size of the “gift of nature,” also discussed elsewhere in the Tableau: it is assumed that the wealth gained from working with the soil will be worth double the value of the work itself: if a year’s payroll for agriculture is 100 livres (abbreviated as /), the crop produced will be worth 200 /.

We are now ready to tackle the zigzag. We note at the top left that the Productive class transfers 600 / of “produce net” to the Proprietors: this is its annual payment of rent; and the zigs and zags will depict how this rent is redistributed by the flow of production to replenish both classes and to start a second year’s accrual of rent.

We next see that the Proprietors spend half their income on the Sterile sectors, purchasing outputs of every kind except those grown on the soil, and the other half on the output of the Productive class, for which they receive grains, meat, caviar, and plovers’ eggs. Having performed their function, the Proprietors play no further role, and the action devolves to the activities of the Productives and Steriles. Here, both sectors follow the lead of the Proprietors, dividing their incomes equally between expenditures on Productive and Sterile outputs—but with very different consequences. Note that every expenditure that goes to the Productive class results in a dotted horizontal line, whereas there are no such lines resulting from expenditures to the Sterile sector. This is, of course, a depiction of the gift of nature, and we should take a moment to pursue Quesnay’s analysis further.

We begin with the Productive sector which has just received 300 from the Proprietors. The Productive sector now spends one-half its receipts for purchases—clothes, tools, and the like—from the Sterile sector and uses the other half to pay for the work of its labor force (although maddeningly this is not shown on Quesnay’s diagram).* Thus the value of the total “inputs” into agriculture consists of 150 / of the foods needed by its workers, plus 150 / worth of clothes and tools, bought from the Sterile sector. This comes to 300 / of total input which, thanks to the bounty of nature, yields 600 / of output.

Following down the zigs and zags we see this pattern repeated: the Steriles and Productives exchange half of the receipts they get from the other class, and use half for the payment of their own work forces. But with each exchange, the Productives gather a gift from nature, which will be paid as rent, whereas the Steriles do not. In the end, the total of the rental amounts comes to 600 livres, and each sector has likewise received the amounts needed to sustain its own activity.

The zigzag shows us several things—for example, that the required size of the productive sector depends on the leverage of the gift of nature. In our example, if that leverage—which Quesnay knew to depend greatly on the use of farm machinery—were less than 2 to 1, the productive sector would have to be more than half the population to generate a stable flow of output over time.

Moreover, the diagram shows that the ratio of expenditure between the two sectors is crucial, given the allocation of population among the sectors. In our zigzag, the proprietors in our diagram must spend at least half their incomes for productive output to maintain things as they are. On the other hand, if they spent more than half on agriculture, the gift of nature will enlarge the total output of society, including their own rents. If they spend less than half, all incomes will shrink, after a few rounds. What is novel and interesting here is the first demonstration of a systemic relationship between expenditure and income in a commercial society.

Last, the diagram shows that only one class can be taxed without interfering with the production of wealth. It is certainly not the productive class, which is the source of its growth. It is not the sterile class, which just balances its books. Hence the only group that can be safely taxed consists of the Proprietors. This leads to Quesnay’s famous recommendation that the hopeless tax situation of pre-revolutionary France be replaced by a Single Tax on rents. One can imagine the enthusiasm with which it was greeted by the land-owning nobility at Versailles.

Finally, in the face of so much brilliance and insight, what was the fatal Physiocratic fallacy? Essentially it lay in the deception that arises when the final product of a labor process is the same as its original input. To the naive eye, the corn that emerges from a crop is the same as the corn that goes into the ground, and the increase in volume therefore appears as a “gift” from nature—the only visible force at work. By way of contrast, the pots made from clay or the planks made from a tree trunk do not seem to grow in value, because their form changes: the pots do not appear as “more” than the clay in the way that a harvested crop is manifestly larger than its original seed.

Yet, with the crop as well as with the pot, final output requires that labor be applied to the input. Further, the unchanged nature of corn input into corn output hides the fact that the additional bushels of crop may not be net gain. They are required to sustain the labor of “sterile” makers of agricultural implements, as well as of husbandmen. Depending on how generously these needs are met, larger or smaller amounts of output will be left over as a gift from nature. Moreover, take away the agricultural implements made by the sterile sector, and there may not be any increase of corn output over corn input. Physiocracy thus builds its analysis on a misconstrued conception of productivity, restricting it to increases in the output of unchanged commodities, and ignoring the very real increases in wealth produced by machines, not to mention cooks or lumbermen.

11 From Ronald Meek, The Economics of Physiocracy Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1973, p. 96.

12 From Steven Pressman, Quesnay’s Tableau Économique Fairfield, New Jersry, Augustus M. Kelley, 1994, p. 22.

* Anyone wishing to penetrate further into the zigzag, which bewilders as much as it clarifies, should consult the books by Ronald Meek and Steven Pressman cited above.