You know the feeling. You can’t wait for the day to end so you can be together. You look at the picture of you two and your heart fills with joy as a big smile spreads across your face. You feel so light you almost glide, with just your toes barely glancing the floor. You feel giddy, even euphoric. At any moment small woodland creatures are going to hop out to greet you. Birds will twirl around your head. Any minute now Pharrell Williams is going to walk out singing Happy as you dance with the animals. Clap along if you feel like happiness is the truth. It’s a magical, special time. You know you have hit the jackpot of life—you have fallen in love.

This is the feeling everyone is looking for, that sensation that you’re special to someone else, that you’ve found that other person, that “better half,” your soul mate, to experience life with. You have a partner and a friend who loves you with every fiber of their being, and you feel the same way about them. You wonder how you could’ve ever lived without them. You are loved!

A study from the University of Iowa confirms this universal search for love. When researchers looked at the number one thing men and woman wanted in their lives, they discovered it was exactly the same for both—mutual attraction and love.1 Love is what this book is about. I’ll explain where love comes from, how to find it, how long each phase is (yes, there are phases), and how you can make love last. In these pages, I explain the biological processes that create that sensation of being in love. I’ll show you what steps are needed to reach it and how those steps are different for men than for women. I’ll explain why dating can be so nerve-wracking. You naturally desire love, but getting love requires you to be vulnerable. You have an innate fear of being vulnerable. The process of becoming vulnerable goes against your other natural desire for self-preservation.

One of the biggest fears is that you’ll fall in love and become vulnerable while the other person won’t. The pain of unrequited love for some people can be so great that they give up looking for love altogether. But you don’t have to. When you understand how love works, you will be able to make educated decisions that make finding and keeping it almost effortless.

Did you know that love is a chemical reaction that affects your brain? That falling in love is only one phase of a multiphase process? That falling in love changes the way your brain functions? That the actions you take at the beginning of a relationship can either cause the other person to leave or to fall in love with you? That the feeling of “falling in love” lasts for a predictable amount of time? That “falling in love” and “being in love” are very different things? Not only that, but you don’t have control of the neurological changes associated with falling in love, but you do have control of being in love. But the most important thing to know is that love is a biological process, and once you understand the science behind the way love works, it makes finding and keeping love easy.

Over the course of this book, I will walk you through the different brain states of love and their biochemical and physiological differences, and how those differences make you feel at each stage. I’ll explain what you can do if you want love in your life, whether new love, to keep a love you’ve found, or to rekindle the spark that you two once had. Understanding the science of love gives you the power to make informed decisions about the most important choice you’ll ever make—to love.

I’m Dawn Maslar, and I’m known as the “Love Biologist.” Before I share what I’ve learned while researching the science of love, maybe I should explain how this all started.

It was an accident—a real, screeching-tires type of accident.

I had recently relocated to southern Florida after a divorce, and my life finally felt like it was coming back together in a better way. I had just landed a coveted, full-time temporary biology professorship at Broward Community College, in warm, sunny, subtropical Davie, Florida.

Only a month before, I had purchased a Yamaha V Star 850 motorcycle. The 850 was fast enough to get me around but not so heavy that it would knock me over if I tried to walk it. A motorcycle is not the most practical or safest form of transportation, especially in a heavily populated area. But when I rode the bike, I felt an exciting sense of freedom. Even more important than the exhilaration of the ride, it provided me with a means to get closer to my bad-boy biker crush.

That’s right, I was a thirty-something divorced woman with several degrees and a big, fat, teenage-like crush on a biker. He was rugged and unconventional, with long, braided hair. He worked with his hands; they were gnarled, callused, and damn sexy. He had tattoos on his arms, and he walked with a mesmerizing, sexy swagger that said, “Come and get me, Dawn—if you dare.” I wanted him, but I didn’t know how to get his attention. I knew I was going to have to work hard to get it. With that belief, I slowly began interjecting myself into his world; I would try to strike up a conversation with him whenever I could. I also started writing down my thoughts about him. I ended up turning one of those into an article about my attraction to a bad-boy biker, and was then offered a column in a local biker magazine. It seemed that I wasn’t the only woman out there with this type of fascination.

One fateful day, a balmy breeze gently swayed the palm fronds as I biked up the long, tree-lined drive bordered on each side by tranquil ponds, and joined the rest of the campus traffic. At the top of the road was an intersection with a parking lot. I saw the late-model, silver, four-door sedan waiting to cross the road. Motorcycle schools warn you that intersections are the most dangerous spots for motorcyclists (where the majority of motorcycle fatalities occur). Therefore, you’re advised to make eye contact with the driver whenever possible.

As I approached the intersection, I looked at the driver. We made eye contact. I knew she saw me, and that I had the right-of-way—even though a right-of-way is an absurd concept for a biker (like an ant thinking he has the right-of-way when he meets a shoe).

As I entered the intersection, I saw a flash of silver out of the corner of my eye. The driver had pulled out, and I was going to hit her. This is one of the worst types of accidents for a motorcyclist. If she hit the side of me, I would go down, maybe break a leg or an arm, but if I hit the side of her car, I would most likely be launched over the hood. This is the nastiest type of accident because you often land on your head. The outcome might be a broken neck, brain damage, or death.

The next thing I remember is watching my motorcycle skid sideways through the intersection without me. I should’ve heard noise, but it was as if I were listening underwater. In dreamlike slow motion, I looked down and saw that I was standing in the middle of the intersection. A silver fender was just an inch from my thigh. There was no blood. I turned and looked at the driver. She looked back at me, her face twisted in terror, and then looked away. Someone ran up from behind me.

“Are you okay?” he asked.

Two more guys ran up, picked up my motorcycle, and walked it off to the side of the road.

I felt my legs, then my head. I was still wearing my helmet. I was fine. I walked over to my bike. It had a few scratches on the handlebar grips, but it looked intact.

“Should I call the police or campus security?” the man asked.

“No, I’m okay. I just need to get to my office,” I said.

He waved. When I turned back, the silver car was gone.

I tried to jump right back on the bike, but my legs began to shake violently. Somehow I managed to maneuver the bike into a parking spot and scurried to my office. I was scared and needed comfort. I decided to call him.

In my mind, this was the perfect scenario. I fantasized about what would happen next. I would call Dirk (not his real name, but it should’ve been) and it would play out like this:

“I was in an accident,” I would say.

“Oh my God, are you all right?” he would ask.

“Yes, but I’m shaking like a leaf. I’m not sure I can ride my bike back home,” I would say.

“Oh no, don’t worry about that. I’ll come and ride your bike home for you. Then we can grab some dinner,” he would say.

He would don his Superman cape, swoop down, and rescue me. He would take me home and hold me with my face buried in his muscular chest. I would breathe in his musky scent until my fears subsided. Then he would guide my chin to bring my lips close to his. Our kiss would melt into an evening of enchanted lovemaking. Oh, this was going to be good.

It was time to turn this fantasy into reality, so I dialed his number.

“Yeah.”

“Dirk?”

“Yes.”

“It’s Dawn; how are you?

“I’m fine, but . . .” he paused.

“What’s wrong?” I asked.

“I really can’t talk to you.”

What? Wait, this was not how it was supposed to go.

“Is this a bad time?” I asked.

“Well, no. I really can’t talk to you anymore,” he said.

“Anymore?”

“Yes, I need to stop talking to you.”

“Why?” I whined like a two-year-old.

“I met someone, and I asked her to marry me.”

I was stunned. I looked at the phone, which had fallen, along with my hand, onto the desk. Whether the cause was the accident or his words—most likely a combination of both—I was in shock. How could he marry someone else? What was I doing wrong?

• • •

This painful experience, and the realization that resulted from it, changed my life. I embarked on a type of healing that helped me break my addiction to men who couldn’t love me. I was so enamored by the process that I wrote a book about it titled The Broken Picker Fixer. It was instantly successful. Overnight, I had a radio show and an advice column on a popular website. I sold the rights to the book and it was republished under the title From Heartbreak to Heart’s Desire: Developing a Healthy GPS (Guy Picking System). The next thing I knew, my weeks were filled with writing, workshops, and coaching calls. I loved it, but at the end of the day, I still had that nagging question . . . How? I now knew how not to pick the wrong men, but I really wanted to know how to find lasting love with the right man.

I wanted to understand what it takes to find enduring love. I wanted a best friend and a lover. I wanted someone who I could travel this life with, a trusted, loving partner. I wanted to be one part of the little old couple sitting on the park bench, holding hands and reminiscing about our wonderful life together. I wanted to know how to get there.

I began by spending hours in the self-help/relationship section of the bookstore, but I walked away consistently unsatisfied with opinions and rules. Most of the advice was empirical and based on the author’s beliefs or personal experience. I wanted more. I wanted facts derived from hard science. If there were biological principles surrounding love and dating, I wanted to understand them. I wanted to be able to apply them to any situation. I wanted to understand the way love works so I could follow that path all the way to that park bench. And, I’m glad to tell you, that’s what this book does.

HOW DOES LOVE WORK?

I’ve heard this question more times than I can count in workshops, coaching sessions, and presentations, and it’s the question I set out to answer after my divorce and the subsequent relationships that seemed promising but went nowhere. During the many years I spent looking for the answer, I riffled through hundreds of stacks of dusty library journals and researched sources as diverse as Psychoneuroendocrinology and People magazine. I combed through dozens of self-help relationship books, but I found them difficult to trust. Many are based on the author’s personal opinion, or what so-and-so’s great aunt did to land her husband back in the 1950s. Two of the bestselling dating books for women were not only written by men, but they were written by male comedians. I had to wonder if the advice they offered was valid or just another punch line. Would they one day jump onstage and say the joke was on us?

So I did what any good scientist would do: I started researching the biology behind love. Why is this question so important? Because once you understand how love works, you can make educated decisions. You will no longer be wondering, I like him; what should I do now? or How long should I wait to have sex? or Geez, things seemed to have cooled off some; are we falling out of love? You will know exactly what’s happening and what actions to choose during each phase. And if things don’t go exactly the way you hoped, you’ll know what changes you can make.

Right now you might be wondering, “Why did a book like this take so long?” Allow me to explain.

LOVE RESEARCHERS: SCIENTIFIC BLACK SHEEP

In 1975, former U.S. senator William Proxmire decided to make a name for himself by creating the Golden Fleece Award. This award was to be presented to any research project that Senator Proxmire considered a frivolous waste of taxpayer funds. Would you like to guess which project received the first Golden Fleece Award? In March 1975, Proxmire awarded the first Golden Fleece award to the National Science Foundation for spending $84,000 to study why people fall in love.2

Thanks to the Golden Fleece Award, the research on love became a type of scientific third rail. Love was considered such an irrational subject that researching it could jeopardize a scientist’s career. Once a Golden Fleece award was given, the researchers’ funding dried up. Therefore, any prudent scientist simply picked a less controversial subject.

Of course, there have been a few brave souls willing to risk poverty and public humiliation to conduct research about love, including anthropologist and science-of-love pioneer Dr. Helen Fisher of Rutgers University, who today is one of the most referenced scholars in the love-research community. I’m forever indebted to those pioneers. Thanks to Dr. Fisher, Dr. Arthur Aron, and others you’ll read about here, I’ve been able to assemble the biochemical and neurological model of our pathway to real love.

Contrary to popular belief, love is not a mystery. Love is logical . . . or should I say biological? Not only does it make sense, but it follows a definite and specific four-step pattern. Improvements in research techniques, new equipment (such as functional magnetic resonance imaging [fMRI], which can locate love in an area in the brain), and openness on the part of the research community to study love have resulted in a flood of new information.

LOVE IS A BIOLOGICAL NEED

What we call “love” is a biological drive. In fact, it’s your greatest biological drive—in some cases stronger than any desire for power, property, and prestige. For example, imagine being the king of a great nation. You control vast sums of money and have immense influence and authority—but you must give it all up if you want love. Sound like the plot of some corny romance novel? Could love be so powerful that someone would give up abundant wealth and dominance for it? Could love trump other desires, such as prestige and safety?

It can, and it has. In 1936, King Edward VIII of England faced this decision. He was in love with Wallis Simpson, an American-born woman who was not legally divorced. Since her status precluded her from becoming queen, the prime minister gave King Edward an ultimatum—he could claim the throne or Mrs. Simpson, but not both.

Edward announced his decision to the world, saying, “I have found it impossible to carry the heavy burden of responsibility and to discharge my duties as King as I would wish to do without the help and support of the woman I love.” 3 And, with that, the king abdicated his throne to marry his beloved.

Love is that powerful, but this story pales in comparison to the real power of love. Love is such a strong drive that without it, a person could actually die. As Helen Fisher says, “This drive for romantic love can be stronger than the will to live.” 4

THE POWER OF LOVE

In the 1960s and ’70s, American psychologist Harry Harlow performed a series of controversial experiments to test the theory that without love, we would die. Harlow decided to completely isolate an infant rhesus monkey from its mother. Rhesus monkeys are more mature than humans at birth, and unlike human infants, baby monkeys can move around on their own soon after birth. Harlow’s experiments involved placing an infant monkey in a room with a surrogate, cloth mother. When the surrogate was present, the baby was observed exploring the room. However, when the surrogate was removed, the infant monkey would crouch, rock, and cry.

If the baby was left alone even longer, it entered a second, passive phase called despair, marked by inactivity, disinterest in the environment, a slouched posture, and the appearance of grief. 5 Harlow stopped the experiment. He realized that if left in the room alone any longer, the baby monkey might have died. He felt certain that this would have happened, even if the baby were given adequate food and water.

The monkey’s reactions mirrored a similar depressive reaction observed in human infants, referred to as hospitalism, a deadly condition noted by Dr. Floyd Crandall in 1897. Dr. Crandall had been criticized for sending babies home to less-than-ideal hygienic conditions. He said his decision was “necessary in most hospitals to save the baby from hospitalism, a disease more deadly than pneumonia or diphtheria.” 6

Dr. Crandall observed that the death rate of infants under one year of age in hospitals was excessive. 7 Surprisingly, he realized that the better the hospital, the more likely the baby would die. This observation was counter to what would be expected. As Dr. Crandall noted, “It is difficult to understand why children placed in comfortable and beautiful surroundings should, after a time, begin to pine, and gradually waste away.” He observed that the babies frequently died from marasmus—wasting away without the presence of organic disease. In other words, the babies were no longer sick, and there was nothing clinically wrong with them; they just died.

After close observation, Dr. Crandall realized the causal link. The deaths were most prevalent in larger hospitals. The larger and better-equipped hospitals had incubators, while smaller hospitals did not. In the smaller hospitals, the nurses were required to take turns holding the infants in their arms. Dr. Crandall figured out it was the lack of loving care, in the forms of holding and caressing, that was causing babies to perish. The infants had ample milk, warmth, and health care, but if they lacked love, they became lethargic and died.

In today’s neonatal wards, parents are encouraged to take turns talking to and touching their babies. Incubators are equipped with sleeved gloves so the babies may be touched while a controlled environment is maintained. Anyone can provide a baby with the best medicine, the most nutritious food, and life-giving oxygenated air, but without that one essential ingredient of love, the baby could still die. The critical component for everyone to survive and thrive is love.

HERE’S THE SHORT VERSION OF LOVE

The grand prize of love, the thing we’re all hoping to find, is the euphoric sensation we call “falling in love.” You feel happy and giddy. You might even feel like you’ve stumbled onto the key of happiness and you want to run around and tell everyone.

Falling in love is an actual biological state of mind. Although it feels wonderful, fMRIs show that the parts of your brain that are critical for your survival are actually deactivated. This is why you feel so great. It’s also what causes you to know that you’ve just discovered “the one.” This neurological anomaly helps you to be more vulnerable to your beloved.

However, the very phenomenon that causes important parts of your brain to shut down is what also makes falling in love so risky. Yet we seldom think it’s risky, because it’s such a strong biological drive. This dichotomy makes finding love difficult. On one hand you want and need it, while on the other hand, vulnerability to someone else makes it dangerous. If you fall in love with the wrong person (like so many do), you can get your heart broken.

To help keep you safe, Mother Nature provides natural biological obstacles to love. You can think of them as protective gates that only allow certain people in. These protective mechanisms are innate. Most are subconscious reactions that scrutinize anyone who tries to “get in.” And if this isn’t bad enough, these mechanisms are different for men than they are for women. When you don’t understand what these mechanisms are, it can feel like the path to love curves through a land mine field. One false step and the whole thing blows up. The only people you seem to attract are not attractive to you. Or you think you had a great date, but he never calls back. It can be frustrating.

And it can get worse. Just when you think you’ve finally found the one you want to spend the rest of your life with, that enchanted feeling begins to wane. You see, the neurological state of falling in love is temporary. You can’t walk around with important parts of your brain shut down forever. Eventually, you need to reach a state of homeostasis, of relative stability. When this happens, things can change, often in sudden and not-so-loving ways. Your critical judgment, which was suspended during the early stage of attraction, returns, and in some cases you wake up one day, look at your beloved, and think, What was I thinking? It’s during this time period when most marriages in the United States end in divorce.

That’s the bad news. The good news is that by reading this book, you will understand that love is not an event but a process with distinct biological phases. I’ll explain what neurotransmitters (chemicals that help your cells communicate with one another) are involved. I’ll explain that to fall in love, a woman has to have two neurotransmitters that build up to a certain level, while a man needs three. I’ll explain what they are and how that occurs. I’ll also explain how your behaviors can help or hinder the process. I’ll also tell you what happens to you when you fall in love but, more important, what happens after you fall out of falling in love. Don’t worry; it’s not the end. I’ll show you how you two can maintain lifelong love if you want to. I say “if you want to” because some of the cute memes, such as “we find love by chance, but we keep love by choice,” are actually scientifically valid.

UNDERSTANDING BIOLOGICAL LOVE

Your brain has three basic evolutionary layers. The innermost layer is the oldest. It’s sometimes called the reptilian brain or ancient brain. Most animals, including birds and lizards, have this core. It houses instincts that drive you to seek survival basics, such as food, safety, shelter, and reproduction. If you’ve ever walked into a place and smelled something delicious, like fresh-baked bread or cinnamon rolls, and the next thing you know, you’re standing at the counter with money in your hand, even though it goes against the diet you just committed to, your ancient brain was probably at the wheel. Your ancient brain can sometimes get you in trouble, but it’s also the place where love begins.

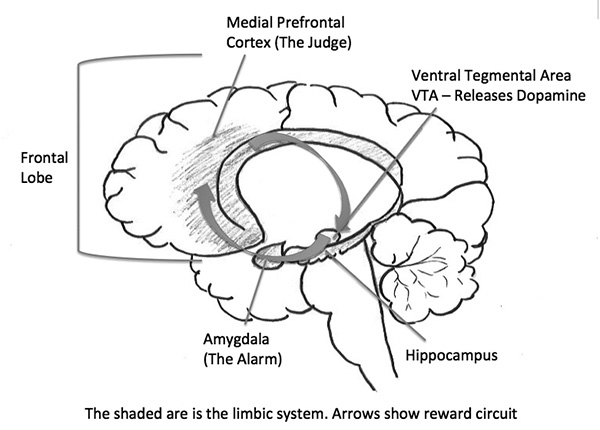

The next layer is the emotional or mammalian brain. As the name implies, most mammals have this layer. In humans, it includes a structure called the limbic system, which houses emotions and memories. The limbic system contains important structures, such as the amygdala and the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC). These structures are critical players on the path to love. In order for sexual attraction to become love, it must successfully pass through this minefield of emotions and memories to eventually reach the home of real love, the neocortex.

The third layer is the neocortex. Neo means “new” and cortex means “bark” or “layer.” Because it’s the outer layer, the neocortex is sometimes referred to as the “thinking cap.” It’s the last layer to evolve, and gives us the ability to think, judge, reason, and really love.

Figure 1. The Brain

CRAZY IN LOVE

Before I started this research, I thought love was like a light switch, it was either on or it was off. Either you felt it, or you didn’t. However, what I discovered is that love changes and evolves. Researchers use fMRI, a type of brain scan, to discover what part of the brain “lights up,” or is employed, during different activities. 8 As you move through the phases of love, different parts of your brain light up or go dim.

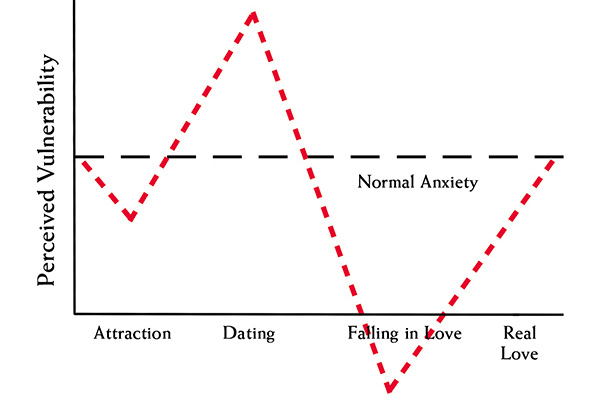

At the same time, your neurotransmitters, those chemicals that allow the different parts of your brain to communicate with one another, increase and decrease. This can cause your head and your heart to feel dynamic emotional shifts. It can also cause your anxiety level to fluctuate, or should I say your “perceived anxiety” level. I say “perceived” because at the early stage of attraction, your stress hormones are extremely high, which normally would make you feel like a nervous wreck, but because the part of your brain that should be responding to the high cortisol level is shut down, instead you feel euphoric. The increased perceived anxiety at the beginning of dating can make you feel uncomfortable and eager to do something. In fact, it’s this fluctuating angst that can make finding and maintaining love tough, because your feelings keep changing.

This chart shows the dramatic fluctuations that can occur as you move through the phases of love. I’ll explain what you can do to mitigate these emotional upheavals, but first, allow me to explain what the four stages are.

Figure 2. Fluctuations of perceived vulnerability

during different stages of love

PHASE 1: ATTRACTION

When you first meet someone new, the fMRI indicates activity in the ancient, more primitive part of your brain. 9 Attraction and desire begin in the center, or subconscious, region. Since this is not the thinking part of the brain, an attraction may not make logical sense. In fact, it may only make sense to your senses. That is to say, just as an alligator naturally moves into the sun to get warm, or into the water to cool off, you naturally move toward environments and people whom you sense are favorable. You’re subconsciously pulled toward some people and repelled from others.

You feel this pull as a physical response. Your body tells you when it’s sexually attracted to someone by releasing norepinephrine, a neurotransmitter that affects your sympathetic and central nervous systems (more on this later in the book). This makes your heart beat faster and your palms sweat. You feel excited. But this is just a momentary response of the exciting, norepinephrine-charged initial phase. At this point you have a slight dip in your normal anxiety level, which allows you to get a little closer to take a look at this new and interesting stranger.

PHASE 2: DATING

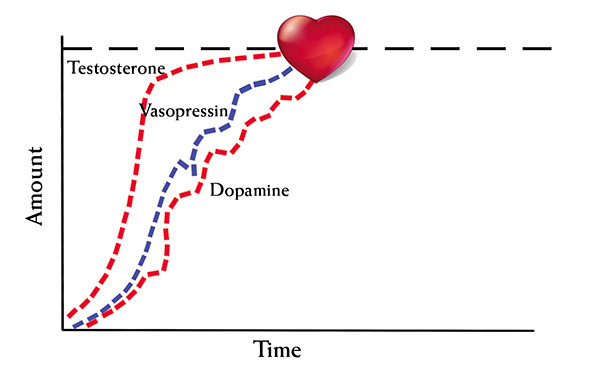

Once your body registers an attraction, you can choose to act on it or allow it to dissipate. One way to act on it is to move into the next phase: dating. If you choose to move into dating, a new neurotransmitter, dopamine—the neurotransmitter of your reward center—comes into play. Every time you enjoy yourself with someone or while doing something, you produce dopamine. This trains your brain to know what you like. Most types of rewards—such as food, drugs, and sex—increase dopamine.10 The increase is perceived as pleasurable and makes you want more.

During courtship, the pivotal point between sexual attraction and falling in love, other gender-specific neurotransmitters team up with dopamine, which is why your anxiety level increases. Falling in love is a big deal because you become extremely vulnerable to the other person. Because of this vulnerability, Mother Nature doesn’t want you to fall in love with just anyone. As you get closer to falling in love, apprehension can increase, especially in men.

Dopamine is the common dominator between men and women. However, men and women fall in love differently. It appears that a woman falls in love when her dopamine and oxytocin levels reach a certain level. In a man, dopamine, vasopressin, and testosterone levels must increase to a certain level for him to fall in love (we’ll define these hormones and explore how they affect the different stages of falling in love beginning in Chapter 2).

Figure 3. How Women Fall in Love

Figure 4. How Men Fall in Love

Since there are several different types of neurotransmitters at play in two different people, the effects they prompt do not always happen at exactly the same time. Because of this, love can be risky. It’s during this courtship or dating phase that each person must grapple with his or her desire to take a risk on love. That’s why the anxiety level is so high.

Being the first one to fall in love is dangerous. What happens if the other person doesn’t reciprocate your feelings? You could suffer painful, unrequited love. This dating phase is fraught with danger, which is why most books are written about it. You want to try to understand what’s happening in the other person’s head.

Part of the problem is that men and women often make decisions based on their assumptions of others’ intentions, or they predict the actions of the opposite sex based on how they themselves would respond. This is a big mistake. The differences between men and women go far beyond body parts. Each gender has unique brain chemistry and different needs, and each is under different biological pressures. Understanding how men and women typically react during the courtship phase can make dating easier, especially if the ultimate goal is love.

I’ll explain how these chemicals accumulate in each person and how their behavior can affect how quickly they accumulate (or if they accumulate at all) as we journey through this book. I’ll also explain the one thing that may make a man fall in love almost instantly.

PHASE 3: FALLING IN LOVE

This third phase is often the one most people think of when they refer to love. This is the phase of mental instability, or the insanity of falling in love and losing your mind. This is where you become obsessed with your beloved, and, at the same time, blind to any of his or her faults. This is why you’re so vulnerable. You also become nervous, excited, and even euphoric as you spend as much time together as possible, often in a horizontal position. This is the glorious phase celebrated by poets and philosophers.

Falling in love is a period of extreme vulnerability, but it doesn’t feel like it, because Mother Nature has shut down parts of your brain that should be telling you to be alarmed. That’s right. Allow me to repeat that: When you fall in love, important parts of your brain, sections that are critical for your survival, are taken off-line. This is why when you fall in love, your anxiety dissipates; all you feel is toe-curling euphoria and absolute certainty that you have just found “the one.”

Many great love stories end with this phase—the knight wins the princess and they ride off into the sunset. However, this is not really the end. As enrapturing as falling in love can feel, this phase is short-lived.

But don’t worry. There is another phase after falling in love. It’s the glorious culmination of evolution—real love.

PHASE 4: REAL LOVE

In the real love phase, love completes its neurological expansion. There is still some sexual passion activity in the primitive brain, but now the majority of the activity is in the prefrontal cortex—your higher brain.11 Real love is calmer, nurturing, and more self-aware. An emotional transformation takes place. Now you’re more concerned with giving than getting. This is the type of love that can last a lifetime. When you see the cute older couple sitting on the park bench, still holding hands after fifty years together, this is the type of love they share.