The duel between Rattler and Alecto.

T he great three-decked ships of the line of the early nineteenth century were still in the direct line of development from the Revenge of 1577. The Royal Sovereign of 1642, the Victory of 1765 and the 120-gun Caledonia of 1808, despite the technical improvements in ship design, all had essential features in common. They were wooden-built, dependent on wind and sail, and were armed with broadside-mounted, muzzle loading guns firing solid shot. The revolution in ship design in the mid-nineteenth century saw the advent of iron and steel construction and armour, steam power and turretmounted breech-loading guns firing explosive shells. All of these innovations were greeted with a good deal of caution, and each posed considerable technical problems, but in total they transformed the world’s fighting navies in a generation.

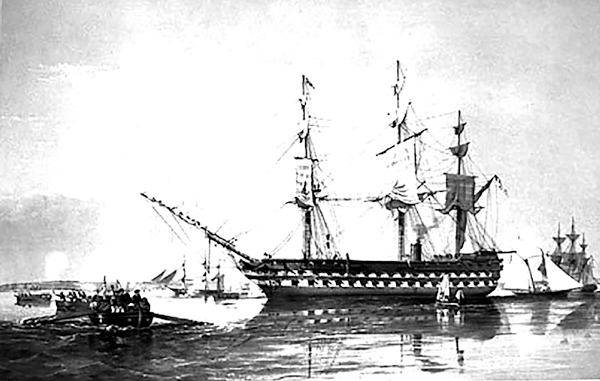

Although steam power conferred the immense advantage of independence from the wind, it suffered from massive drawbacks. Engines were prone to breaking down in the early years. Aboard a wooden warship even the galley fire was a hazard and boiler rooms seemed terribly vulnerable to gunfire; paddle wheels were similarly vulnerable and even more exposed. Moreover the rate of consumption of coal meant that no vessel intended for the open sea could be solely dependent on her engines. However, by the 1820s, the navies of France, Britain and the USA were among those using steam paddle tugs for harbour work. Experiments with the far more efficient screw propeller were made in the following decades, with the Americans launching the first screw warship in 1843, the 10-gun sloop Princeton. Two years later the Admiralty staged the famous duel in which the screw sloop Rattler was lashed stern to stern with the paddle steamer Alecto, of similar size and power, in a tug-of-war. Alecto suffered the indignity of being dragged backwards, while at full power, at almost three knots.

The duel between Rattler and Alecto.

The screw frigate Ajax was the first of a series of warships to be built as a result and by 1850 screw propulsion was being applied to firstrates, the 90-gun Agamemnon among them, while existing ships were converted to steam.

However, for the next twenty years steam was regarded as providing auxiliary power only and a full sailing rig was an essential part of any warship. Moreover, an emphasis on sail-drill and seamanship as the priority, at times hindered development.

The use of the explosive shell was not unknown in naval warfare in the eighteenth century. The ungainly bomb-ketches of the time mounted one or two mortars amidships, the whole vessel having to be aligned in the direction of fire. The explosive was detonated by a fuse of slow match, lit before the propellant charge of gunpowder was fired. This was not only a hazardous operation aboard a wooden ship, but the rate of burning of the fuse was unreliable. Resulting accidents suggested that the shell was not really suited to naval warfare until, in 1824, the invention of a French artillery officer solved the problem. Colonel Henri-Joseph Paixhans tested a shell-firing gun in which the fuse of the shell was lit by the flash of the propellant, so that until the gun was fired, the shell was safe.

HMS Agamemnon.

Around the same time came experiments with breech loading and with rifling, to improve accuracy, but difficulties with the construction of a reliable breech mechanism led the Royal Navy to the continued reliance on muzzle-loaders until 1879. Then an accident occurred when a 38-ton muzzle-loader in Thunderer burst. It was discovered that the gun which had misfired, had been reloaded again by mistake and that the double charge had shattered the barrel. Muzzle-loaders of the time were reloaded by being depressed in line with angled reloading tubes set in the deck, with the charges and shells inserted by a hydraulic ram. The noise had been so deafening that the gun crew had failed to realise that one gun had misfired. Such an error would, of course, be impossible in a breech-loaded gun.

Guns of this size and larger (a 100-ton gun was produced by Armstrongs in 1876) could not be carried in large numbers by the wooden ships of the line, so a form of mounting had to be devised to bring the main armament to bear on either broadside. Guns were either mounted in a revolving turret, or on a turntable behind an armoured barbette; the first experiments with turret-ships were made in the 1860s.

Armour was clearly vital for protection from shell-firing guns: the destruction of an unarmoured Turkish squadron by the Russians at Sinope in the Black Sea in 1853 was proof of this, if proof were needed. The earliest ironclads were simply wooden ships fitted with an armoured belt, though it must be remembered that by 1820 such vessels also had ribs of iron. The first ironclad was the French Gloire, a two-decked screw vessel cut down to a single gun deck and given a simpler sail rig and armour in 1853. Two sister vessels were similarly altered and a fourth ship, Couronne, was laid down. These singularly ugly ships stirred the Admiralty into action and in 1859 the first British ironclad, Warrior, was laid down. Along with her half-sister Black Prince and Couronne, she was the first iron battleship, although classed as a frigate since she had only one gun deck.

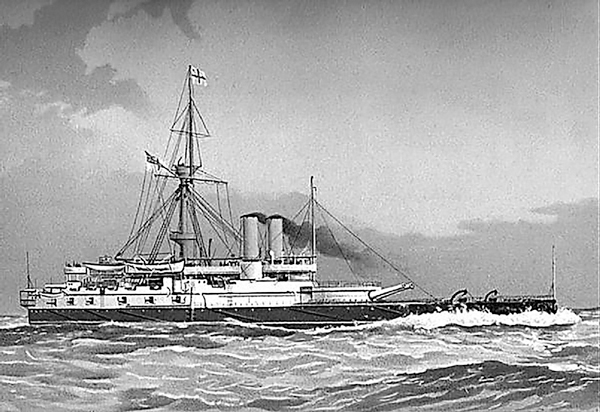

HMS Warrior.

Of 9,200 tons displacement, Warrior was the largest ship then built, was capable of 14 knots and mounted thirty-two muzzle-loaders on the broadside. Reclassified as an armoured cruiser in 1867, she and Black Prince were placed in reserve in 1871 and then withdrawn from service in 1883. Black Prince saw service as a training ship before being scrapped in 1923, but Warrior survives. She became part of the Navy’s Torpedo Establishment at Portsmouth in 1904 as Vernon III, her own name being transferred to a new armoured cruiser. Twentyfive years later she was towed to Pembroke Dock at Milford Haven where she served for fifty years as an oil jetty under the inglorious name Oil Fuel Hulk C77. With her deck concreted over and a line of huts and street lamps along it, she refuelled over 5,000 ships in these years, before restoration became an issue. Ownership was transferred to the Maritime Trust in 1979 and she was towed to Hartlepool for the work to be carried out. Restored, she was towed to Portsmouth in 1987, where she still dominates the harbour.

Figurehead of HMS Warrior.

Oil hulk.

CSS Virginia (ex-Merrimack).

USS Monitor.

By 1862 then, the three innovations of steam power, armour and shell-firing guns had been accepted as the basis of naval design. But apart from some minor actions, there had been no battle to test the new ships. Neither the British nor the French navies saw action in the 1860s, but the Americans had been well abreast of naval developments and were fighting their Civil War. Here the Confederate States, in possession of the Navy Yard at Norfolk, Virginia, set to work on the hulk of the steam frigate Merrimack. In dock for an engine overhaul, she had been set on fire and scuttled by her Union officers on the outbreak of war. Now salvaged, she was cut down almost to the waterline and a long, sloping casemate of timber, faced with four inches of railway iron was built. This was pierced with ten gun ports and the vessel, renamed Virginia, set out to attack the Union shipping in Hampton Roads. She sank the 24-gun sloop Cumberland and forced the 44-gun frigate Congress with her sisters Minnesota and Roanoake to run aground.

Battle of Hampton Roads.

At nightfall there arrived off Hampton Roads one of the strangest vessels ever seen. The Union’s response to the conversion of the Merrimack had been the rapid construction of the Monitor to the design of the Swede John Ericsson. A shallow-draught hull was provided with an armoured deck, a conning tower and a centrally-mounted turret housing two 11-inch smooth-bore guns. Aptly described as ‘a cheesebox on a raft’, she had struggled down from New York, so that when Virginia emerged to complete her work of destruction, she faced another ironclad. Their gun duel was something of an anti-climax. The defensive armour of each vessel far outclassed the hitting-power of their guns as the two manoeuvred ponderously and fired even more slowly, breaking off the action after three hours.

The effect of this action upon naval construction was remarkable and immediate. Not only did the Union decide that the future lay in turreted ‘monitors’ (the name became generic, though the name-vessel foundered in a heavy sea off Cape Hatteras, North Carolina in 1862) but the European powers began to build to this design. The Admiralty breastwork monitor Glatton of 1872 was typical of the French and British examples, but the Russians built two monitors of circular hullform. By this time, however, another lesson of modern warfare had apparently been taught by the Battle of Lissa, in the Adriatic, in 1866. This was the use of the ram – a revival of the battle tactics of the galley. A ship with its own motive power, whether oars or steam, might well inflict mortal damage by ramming, and the Italians commissioned the Affondatore in 1866. Built at Milwall, she displaced 4,000 tons and was armed with two turret-mounted guns, but had as her main offensive weapon a fearsome 26-foot ram.

Italian ram Affondatore.

HMS Hotspur with anti-torpedo net deployed.

At Lissa, she failed to inflict any damage on her opponents, but the Austrian flagship Erzherzog Ferdinand Max did sink the Re d’Italia by ramming.

The British turret-ram Hotspur was designed in 1868 on the assumption that ‘the ram, and the ram only, need be feared at sea’, the lack of success of the purpose-built Affondatore being conveniently overlooked. The Polyphemus was originally laid down in 1882 as a ram without any other offensive armament, but was completed as a torpedo-ram in an attempt to blend another innovation into the pattern of development. None of these craft had any success in action, though one finds an interesting fictional example in H.G. Wells’s The War of the Worlds in the destruction of a Martian fighting machine by the ‘torpedo-ram Thunder Child’.

Torpedo ram warship HMS Polyphemus.

HMS Victoria.

That the ram could be a formidable weapon – albeit in peacetime and against consorts – was proved by frequent accidents. Ships of the Russian, French, German and Spanish navies were lost to ramming during manoeuvres, while the Royal Navy lost Vanguard in 1875 (rammed by Iron Duke) and, even more famously Admiral Tryon’s flagship Victoria, rammed by Camperdown in the Gulf of Sirte in the Mediterranean in 1888.

The early turreted monitors were all essentially coastal defence or bombardment vessels, too slow and unseaworthy to work with a fleet in the open sea. In 1864 the Admiralty laid down its first turret ship, Prince Albert, and had begun the conversion of the three-decker Royal Sovereign into another. Each carried four guns in turrets mounted on the centre-line, but they too were coastal defence ships. In the plans for a sea-going equivalent the insistence of the Admiralty on a full sailing rig and a high freeboard led to a most unsatisfactory compromise in design. The very weight of the turret meant that it could not be carried high above the water-line without adversely affecting the ship’s mobility, while the rigging masked the all-round fire of the guns. Monarch was laid down in the Admiralty dockyard at Chatham in 1866 and was completed three years later. Her main armament of four 12-inch guns was carried in two paired turrets amidships, limiting their use as there was no possibility of end-on fire. She displaced 8,300 tons and had a freeboard amidships of 14 feet, with an armoured belt and a central citadel. With her masts and yards removed during a lengthy refit from 1890–97, she remained listed as a fighting unit until 1904, though with her obsolete muzzle-loading guns she could scarcely have been regarded as effective.

HMS Captain.

By contrast, the career of her contemporary Captain was tragically short. Designed to displace some 7,000 tons, she turned out to be very much overweight and so her already low freeboard was reduced even further. Only months after she joined the fleet in 1870, she capsized and sank in a squall in the Bay of Biscay, taking her designer, Cowper Coles, and most of her crew with her. The sailing rig was to continue in use in the next decade, but to many critics it was both hazardous and outdated.