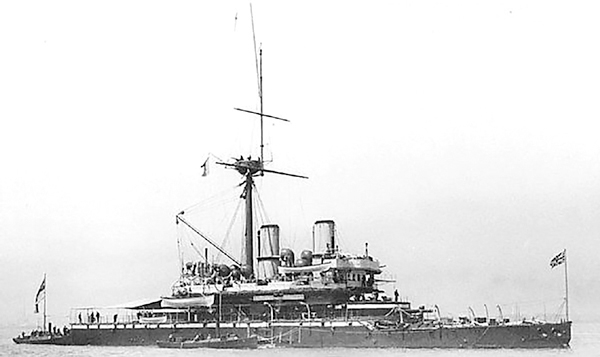

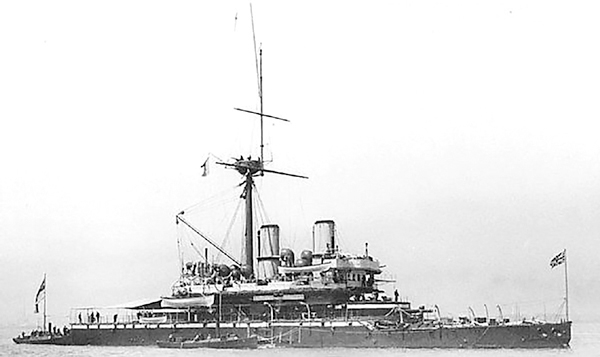

HMS Devastation.

D espite the innovations embodied in Warrior and her successors, the armoured battleship in 1870 remained a vessel dependent in part on sails and largely restricted to broadside firing. But the breastwork monitors Cerberus, Magdala and Abyssinia, completed in that year, dispensed with sails altogether and each mounted four 10-inch guns, disposed in centre-line turrets. Together with the single turret Glatton, they pointed the way to the sea-going mastless ship.

Devastation and Thunderer carried this trend to its logical conclusion and were the first of their type. Displacing 9,300 tons and with low freeboard, each mounted four 35-ton guns in two turrets. When Devastation joined the fleet in 1873 she aroused great controversy. To the advocates of sail the squat, unlovely ship was a monstrosity, while her supporters waxed lyrical over her craggy virtues – she was ‘an impregnable piece of Vauban fortification, with bastions, mounted upon a fighting coal mine’. Her full load of 1,800 tons of coal gave her a cruising radius of 4,700 miles and she had 2,500 tons of armour. Rearmed in 1891 with four 10-inch breech-loaders, the two ships served until 1907 by which time Dreadnought, which they had foreshadowed, had been commissioned.

HMS Devastation.

An earlier Dreadnought, the fifth of her name, was completed in 1879 as a development of the Devastation design with a displacement larger by 1,500 tons, 38-ton guns and even heavier armour. She was the ultimate in the breastwork monitor, four smaller versions of which (the Cyclops class) had also been built. There was to be no clear line of development to the later Dreadnought; for the rest of the decade there was to be a return to the sailing rig. The French central battery ship Redoutable had a full rig of sails, while her half-sister Alexandre had a barque rig, with fore-and-aft sails on the mizzen mast. Temeraire had a massive two-masted brig rig and mounted her four 11-inch guns in barbettes fore and aft.

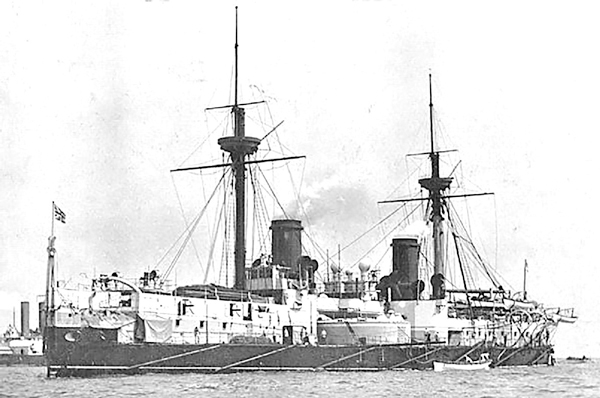

The ultimate in the masted battleship came in 1881 with Inflexible. She had the heaviest armour ever given to a warship before or since – 24-inch at its thickest – protecting a central citadel in which were mounted two circular turrets, each with two 16-inch guns. She was originally brig-rigged with two immense masts, though it was never intended that she would fight under sail, and when rebuilt in 1882 the sailing rig was removed.

She had been laid down as a reply to the Italian Dandolo and Duilio and was followed into service by two scaled-down versions, Ajax and Agamemnon. These, the last battleships in the Royal Navy to be armed with muzzle-loaders, have been described (by naval historian Oscar Parkes) as ‘two of the most unsatisfactory ships ever built’ for the Royal Navy, and the next three acquisitions were little better. Two coastal defence ships, then building in a British yard for Turkey, were purchased and renamed Belleisle and Orion, and the third was the last broadside monitor Superb. Also purchased was Independencia, building at Millwall for the Brazilian Navy. Renamed Neptune, she was a mastless turret ship, resembling Monarch of a decade earlier.

HMS Inflexible (as rebuilt) in 1881.

The squadron, which was dispatched to Alexandria in 1882, epitomised the Royal Navy at this uncertain stage of its development. For the only major naval operation since the Crimean War, the ships were an ill-assorted group. The fleet comprised two turret ships – the new Inflexible and the old Monarch, four central battery ships – Alexandra, Sultan, Superb and Invincible, and the hybrid Temeraire. None of the three major mastless ships was present.

The French, who had at first intended to co-operate with Britain in suppressing the revolt against Ottoman rule by Arabi Pasha, did not do so and, with Egypt effectively passing under Britain’s protection, rivalry between the two countries became intense. Consequently, the developments in French naval construction were watched even more closely. Since 1870 the French had built ten rigged central battery ships, of which the most recent and most powerful were Redoutable, Courbet and Devastation. Still building was Admiral Duperre with four 13.4-inch guns in barbettes, two on the centre line aft of the bridge and funnel, and one on either beam forward. The Italian naval architect Benedetto Brin designed the barbette ship Italia with four 17-inch guns in barbettes mounted diagonally amidships. She and her sister Lepanto achieved 18 knots and each had only a single pole mast amidships.

The Royal Navy had by now abandoned the muzzle-loader after the accident aboard Thunderer in 1879, and Colossus and Edinburgh, laid down in that year, were each equipped with four 12-inch breech loaders; earlier ships were converted during refits. Similarly Inflexible’s yards had been removed, leaving her with pole masts carrying fighting tops and a signal yard, similar modifications were carried out on earlier vessels. This left only Swiftsure and Triumph (on the China station) and the training ships Northumberland, Minotaur and Agincourt with a full sailing rig. The advantages of barbette mounting were recognised, though the much heavier turret was preferred in the ungainly Conqueror and Hero, which proved to have very poor sailing qualities, and finally in Victoria and Sans Pareil. However, Collingwood (9,500 tons), laid down in 1880, mounted her four 12-inch guns in open barbettes 20 feet above the waterline. Four more ships, Anson, Camperdown, Howe and Rodney each carried four 13.5-inch guns on a displacement of 10,000 tons, while Benbow mounted two 16.25-inch. With a heavy armoured belt and a top speed of 17 knots, they were considered to be a match for the latest French vessels of 1881 – Hoche, Magenta, Marceau and Neptune.

The decision to equip Benbow with the heaviest gun available had an unfortunate sequel. After the building of six ships of a basically similar design had given hopes of a more homogeneous battle fleet, there was now another change of heart. It was decided in 1885 that the next two ships, Victoria and Sans Pareil, should mount the giant 110 ton 16.25-inch guns in a single paired turret forward. They proved far from satisfactory and Victoria was only three years old when she was rammed and sunk by Camperdown during manoeuvres in the Gulf of Sirte. Nevertheless, the turret mounting was again chosen for Nile and Trafalgar in 1886. They were the last of the citadel turret ships.

The menace of the torpedo caused doubts to be cast on the future of the battleship in the 1880s. The ‘Jeune Ecole’ of French naval theorists contended that the building of smaller craft would enable a successful guerre de course (commerce raiding) and that this policy would be more rational than attempting to match Britain’s battleship strength. By the end of the decade the Royal Navy had a massive superiority in numbers of capital ships, though the figure included too many outdated or inferior vessels to be entirely convincing. Nevertheless, in 1889 Britain had as many first class battleships as France and Russia combined and twice as many of the second class. A shortage of cruisers meant that the vital trade routes were vulnerable, and the Naval Defence Act of 1889 provided funding for seventy new ships over the next five years, of which forty-two were to be cruisers and ten battleships.

HMS Royal Sovereign.

Since 1886 there had been a new Board of Admiralty, with a new Director of Naval Construction, W.H. White. The oldest ships still in service, including Warrior and Black Prince, as well as Hector, Valiant and Defence were now placed in reserve, and gunnery tests were carried out using the old Resistance as a target vessel. The result was the design for the Royal Sovereign class of seven ships, which marked the beginning of a new era. They were to displace 14,150 tons and to have a cruising speed of 15 knots. The main armament comprised four 13.5-inch breech-loaders, mounted in pairs in two barbettes forward and aft of the superstructure, with a secondary armament of ten of the 6-inch quick-firing guns now regarded as essential for defence against torpedo attack. With a water-line armour belt and an underwater armoured deck, these ships set a new standard for battleship design for the next decade. Oscar Parkes (a severe critic of many of the unsuitable designs of the past years) commented: ‘For the first time since the Devastation set a new standard for unsightliness, a British battleship presented a proud, pleasing and symmetrical profile, initiating a new era of volcanic beauty after two decades of sullen and misshapen misfits.’

Battleship HMS Royal Sovereign, 1891. (© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London)

HMS Resolution. (© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London)

An eighth ship Hood was completed to a similar design, but with turrets instead of barbette mountings. Her lower freeboard, resulting from the great weight of the turrets, made her much inferior to her half-sisters, and she was the last turret ship to be built.

In the second class battleships Barfleur and Centurion, built at the same time and intended for the China station, the addition of protective hoods over the barbettes introduced the turret in its modern form, and the innovation was to be adopted as a standard feature in all subsequent ships of the Royal Navy. Together with the later and slightly larger Renown, these were the last second class battleships laid down for the Royal Navy. Two more, for Chile, were bought in 1904, when it was feared that they might be acquired by Russia.

The ships built under the 1889 Act all served with the fleet until the advent of dreadnoughts rendered them obsolete and they were taken out of service in the years immediately preceding the First World War. By then a new class of super-dreadnoughts was building and the names Royal Sovereign, Royal Oak, Ramillies, Resolution and Revenge together with Renown and Repulse, were earmarked for them.