Admiral Sir John (‘Jackie’) Fisher.

T he last battleships of the pre-dreadnought era embodied technical improvement both in defence and hitting power. The use of nickel steel made for a reduction in the thickness of the armour belt, and to the extension of the area which could be protected on a given tonnage, while the curved armoured deck, double bottom and anti-torpedo bulkheads gave added protection against the new dangers of the mine and the torpedo. More efficient propellants and breech mechanisms improved the main armament and enabled action at longer range outside the menace of the torpedo boats, the quick-firing 6-inch gun being developed as defence against such vessels.

The consequent changes in gunnery theory in turn had a profound impact on ship design. Ranging by firing salvoes was more efficient, but the increasing calibre of the secondary armament began to cause problems. The 9.2-inch guns of the King Edwards had a different trajectory and flight time for a given range than the 12-inch of the main battery, but the shell splashes were not identifiably different, with consequent problems in gunnery control. The clear answer was the elimination of the intermediate battery and the reliance upon heavy guns of a single calibre: the outcome was the building of Dreadnought.

A larger main battery was not in itself an innovation. The Russian battleships of the Ekaterina II class had mounted six 12-inch, in a curious triangular disposition. One of the three barbettes, with a pair of 12-inch guns, was on the centre line aft, while the others were mounted forward on each beam. A decade later the Brandenburgs mounted six 11-inch in three centreline turrets. Then, in 1903, the Italian Vittorio Cuniberti had outlined in Jane’s Fighting Ships a new battleship for the Royal Navy. This was to displace 17,000 tons, to be capable of 24 knots and to carry twelve 12-inch guns in four double and four single turrets. With two turrets on the centre line, eight guns could fire on either broadside and four ahead or astern.

Admiral Sir John (‘Jackie’) Fisher.

At the time the Royal Navy enjoyed a massive superiority over any foreseeable combination of adversaries: in addition to the eight King Edwards and the two Lord Nelsons planned, there were thirty-six battleships of modern design in commission. These, from the Royal Sovereigns to the Duncans, would be so far outclassed by Cuniberti’s ship as to be of limited use, and it was an opinion widely held that Britain should not initiate a change which would eliminate the advantage built up so carefully and expensively over the years.

The appointment of Sir John Fisher as First Sea Lord in 1904 ensured a whole series of reforms in the training of personnel, the disposition of the fleet, and the organisation of an effective reserve.

It also ensured that Dreadnought would be built. The assumption henceforth was that Germany was the potential enemy and the battle fleets were to be deployed accordingly. Previously, the most modern battleships had been assigned to the Mediterranean Fleet; a dozen of the best ships served there, with older ships in smaller numbers in the Channel and Home Fleets, or on detached service further afield. The alliance of 1902 with Japan and the Entente of 1904 with France enabled Fisher to alter the entire pattern. By leaving the Pacific largely to Japan and the Mediterranean to France, he could base an enlarged Home Fleet of sixteen battleships on Dover and an Atlantic Fleet of eight more at Gibraltar. This enabled the bulk of the battle fleet to be deployed against Germany.

HMS Black Prince, 1914.

Fisher next turned his attention to the disposal of elderly ships, still on the reserve list, but of no real fighting value. These included almost forty old battleships, stretching back to Warrior and Black Prince, now rated as armoured cruisers. Others were training or depot ships, but progressively over the next few years all those built before 1885 went to the scrap-yards.

Fisher was not only an advocate of the all-big-gun battleship, but was also aware that the concept was being regarded with some interest by other navies. By 1904, the Japanese were considering the design of a ship of 17,000 tons, armed with eight 12-inch guns, and by the time the two Satsumas were laid down early in 1905, the armament had been increased to twelve 12-inch. Also, in 1905, the new naval programme authorised by the United States Congress approved the building of two South Carolinas mounting eight 12-inch. To Fisher, therefore, the arguments against Britain initiating naval change were unconvincing: that change was already beginning, and it was to Britain’s advantage to seize an early lead.

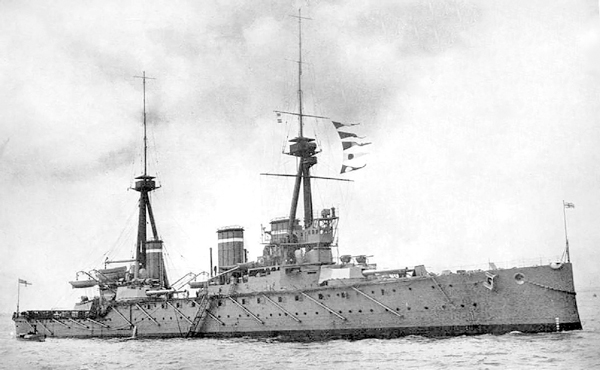

From a series of six draft designs, offering different combinations of engines and armament, the plans for Dreadnought were chosen, and she was given priority even to the extent of using materials already acquired for the building of other ships – including the four 12-inch turrets and a spare, intended for Lord Nelson and Agamemnon. Her keel was laid down at Portsmouth on 2 October 1905, she was launched in February 1906 and commissioned on 3 October 1906. Of 17,900 tons, she mounted ten 12-inch guns in five turrets, three on the centre line and two on the beam, to give a broadside of eight guns, with six able to fire forward. Turbines gave her a speed of 21 knots, but their greater reliability gave her a cruising speed equal to the top speed of earlier ships. Moreover, she was able to hold her speed for hours, whereas reciprocating, or piston engines grew progressively less efficient.

HMS Dreadnought.

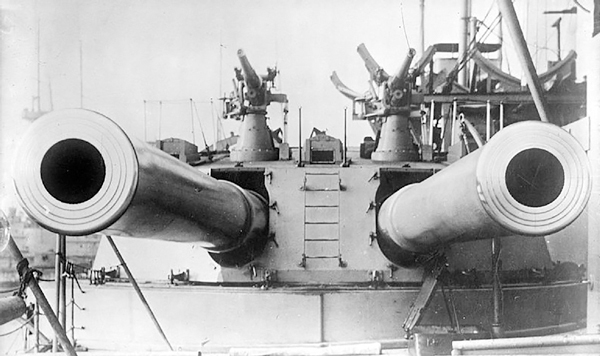

12-inch gun turret aboard Dreadnought.

Although the battleship programmes of Japan and the United States had helped precipitate the Admiralty into building Dreadnought, both of these two countries were on good terms with Britain, and there was no real possibility of a war involving them. France and Russia had been the likeliest adversaries, but since 1898, relations with both of these countries had improved, and it was now Germany on whom suspicious eyes were cast. Political hostility concerning events in South Africa, South America and Morocco was intensified by the German Navy Laws and by the Kaiser’s assumption of the title of ‘Admiral of the Atlantic’ in 1902. Whether this was simply a piece of flamboyance, or whether it had any serious intent, is impossible to assess, but there was no way to ignore the physical presence of the new German battle fleet. Fifteen battleships had been laid down between 1899 and 1905 and these seemed to be a direct threat to Britain’s naval supremacy. This convinced the Admiralty that ‘the German fleet has been designed for a possible conflict with the British fleet. It cannot be designed for the purpose of playing a leading part in any future war with France and Russia, a war which can only be decided by armies and on land’. Germany, it was felt, was not dependent upon ocean trade routes and the need to maintain a margin of superiority over that country became the overriding consideration in British naval planning.

It was to give Britain a lead in the new naval race that Dreadnought had been laid down and completed with such urgency. This had an immediate effect abroad, where naval building plans were halted and amended to take account of the new vessel. The Japanese Satsuma and Aki, laid down in 1905, were not completed until 1909 and 1911 respectively, and then were revealed to be ‘intermediate dreadnoughts’ of the same type as the Lord Nelsons. Eight of the planned 12-inch guns were replaced by 10-inch, with only four 12-inch left as the main armament, a change dictated by economic rather than naval requirements. The American South Carolinas, authorised in 1905, were not laid down until 1906 nor were they completed until 1908. They did, however, incorporate one significant design advantage in their four centreline turrets, in two pairs fore and aft, with the second and third mounted higher than the first and fourth. This device of ‘super-firing’ turrets was not introduced into the Royal Navy until 1909, nor was there a British battleship with a complete centreline armament until 1912. Russia and France did not even begin to build dreadnoughts until 1909 and 1910 respectively, while Italy and Japan also laid down their first in 1909. Germany’s first dreadnoughts were the four Nassaus, begun in 1907, but these were armed only with 11-inch guns, and the first of them did not enter service until 1909.

By then it had been possible in Britain to capitalise on the advantage of the initiative gained by building Dreadnought. Three more great ships had been laid down under the 1905–6 programme and completed in 1908, and three more were begun in each of the 1906–7 and 1907–8 programmes. Yet another four had been laid down before Nassau was commissioned. It appeared that not only the first round, but also the second and third, had gone to Britain, but Germany did not give up, and the naval race was under way.

The three Invincibles, laid down in 1906 and completed two years later, represented another new design concept. In addition to the Dreadnought project, which he had designated HMS ‘Untakeable’, Fisher had been a keen advocate of a fast vessel which he called HMS ‘Unapproachable’. This was to enter service as the battle cruiser, a design which caused yet more controversy. The function of this ship was essentially that of the armoured cruiser, but it was to have the same margin of superiority in speed, armament and range, over existing armoured cruisers as did Dreadnought over earlier battleships. They were to be ‘super-scouting cruisers’ able to press home their reconnaissance of an enemy fleet in the face of hostile armoured cruisers, and were to be fast enough to hunt down commerce raiders. But it was the calibre of their main armament – 12-inch guns in the earlier classes – which led to their being designated ‘dreadnoughts’. This marked them down for a third function in which they were to prove highly vulnerable – as a fast wing to the battlefleet. Three, including Inflexible herself, were to be lost in action at Jutland, proving their unsuitability for this role. However, in 1908 when Inflexible, Invincible and Indomitable joined the fleet, they were hailed as welcome innovations, despite the doubts of the more perceptive. In 1906, when they were still building, Brassey wrote: ‘Vessels of this enormous size and cost are unsuitable for many of the duties of cruisers, but an even stronger objection is that an admiral, having Invincibles in his fleet, will be certain to put them in the line of battle, where their comparatively light protection would be a disadvantage, and their high speed of no value.’

HMS Invincible.

HMS Invincible anchored at Spithead.

HMS Inflexible.

A decade before Jutland, he drew attention to the danger of their magazines being penetrated by plunging fire at long range.

Dreadnought herself was less well protected than her nearcontemporaries, the Lord Nelsons, and her main armament was not disposed to the best advantage. Her fore-funnel was placed immediately abaft the bridge, with the signal mast beyond it, an inconvenient arrangement corrected in the Bellerophons. By the time of the outbreak of war in 1914, she had been so much eclipsed by later developments that she no longer formed part of the Grand Fleet but instead was flagship of the Channel Fleet, composed otherwise of the pre-dreadnoughts of the King Edward VII class, and at the end of the war was sold for scrap. Yet she, like Warrior and Devastation before her, had ushered in a new era of naval design.