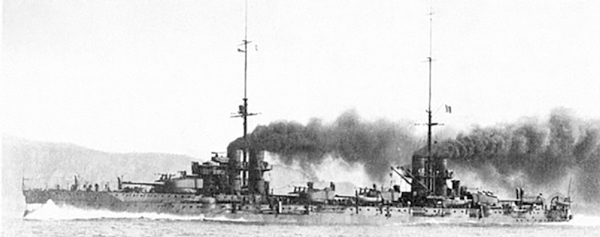

SMS Nassau.

G ermany’s programme of battleship construction, which had begun so well in the years following the passage of the two Navy Laws, received a severe set-back with the news of the building of Dreadnought. Consideration had been given to the building of such a vessel in Germany, but the ships under construction in 1906 were far inferior. The Deutschland was completed in July of that year, but her four sisters were not in service until 1907 and 1908. A projected design with twelve heavy guns, of two different calibres, similar to Britain’s Lord Nelsons, but of smaller size and with lessercalibre guns, had been abandoned in favour of a design with eight 11-inch on 17,000 tons displacement. By 1906, with information available about Dreadnought, this was again modified so that twelve 11-inch guns were mounted in the Nassaus. These were disposed with four of the six turrets mounted on the beam, so that even with two guns more than Dreadnought, they still had only an eight gun broadside of 5,280 pounds against 6,800. With reciprocating engines rather than turbines, and capable of only 19 knots, they were clearly inferior to Dreadnought in all respects save two. In weight of armour and in internal subdivision into watertight compartments, the Nassaus were much superior to the prototype; Germany maintained these advantages in all the first-generation dreadnoughts of the prewar era.

SMS Nassau.

Nassau and her sisters Westfalen, Rheinland and Posen did not join the fleet until 1909–10. By then the Royal Navy had built not only the three Invincible class battle cruisers, but also three Bellerephons. These were basically enlarged versions of Dreadnought, at 18,600 tons, and with sixteen 4-inch guns as anti-torpedo-boat weapons. They retained the wing turret mounting for four of the main calibre guns, although super-firing turrets were incorporated into Minas Gerais and São Paolo, built in British yards between 1907–10 for the Brazilian navy. Collingwood, St Vincent and Vanguard, laid down under the 1907 programme and completed by 1910, were again broadly similar and gave the Royal Navy seven dreadnought battleships and three battle cruisers to the four and one of Germany.

SMS Von der Tann.

Von der Tann, Germany’s first battle cruiser, was laid down as part of yet another revised programme of naval building by Germany. A new Navy Law in 1907 proposed the building of three dreadnought battleships and one battle cruiser each year for the next four years, with two each year thereafter until 1918, to give a total of twenty-eight by 1918. This coincided with a cutback in naval building in Britain by the Liberal government which had taken office in 1906. Impressed by the lead in ships completed and building and anxious to reduce the expenditure upon defence, it determined that only two battleships need be built each year. For 1907–8 indeed, there were originally plans only for two St Vincents, but the failure of disarmament talks at The Hague led to an increase to three. The 1908–9 programme provided only for a single battleship, Neptune, and one battle cruiser, Indefatigable. In each of these, the wing turrets were offset to allow a limited arc of cross-deck fire, enabling the full broadside to be employed. Considerations of blast damage meant that these turrets could not be used for end-on fire, a limitation which applied also to the superimposed rear turrets of Neptune. In reply, the Germans were building the first three Helgolands, enlarged versions of the Nassaus, and the battle cruiser Moltke. For the latter they retained the 11-inch gun, but the battleships were armed with 12-inch, still mounted in hexagon formation with four beam turrets.

SMS Helgoland.

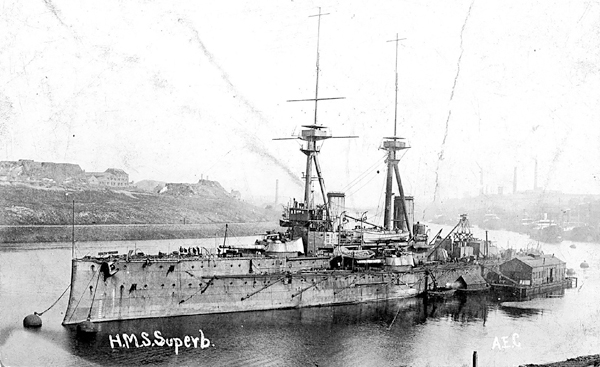

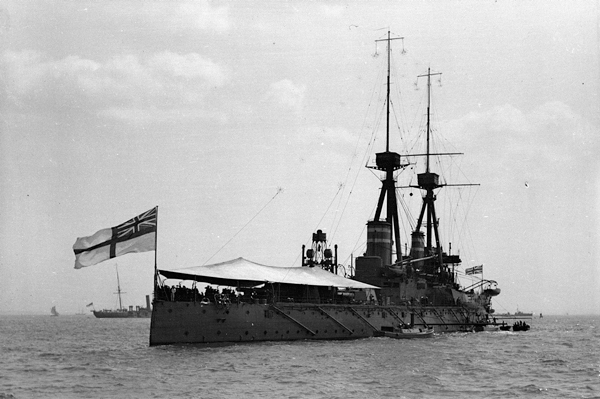

Battleship HMS Superb at anchor at Spithead. (© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London)

Gloomy forecasts of the erosion, not only of the two-power standard, but also of Britain’s naval superiority over Germany, now began to be heard.Various calculations suggested that Germany might achieve a lead by 1914 at the latest, and the government in London was put under heavy pressure to increase its 1909–10 programme. In 1908, when the first moves were made, the Admiralty asked for four dreadnoughts to be authorised for the next year, with a provision for an increase to six if necessary. In this they had the support of Sir Edward Grey, the Foreign Secretary, but were opposed both by Lloyd George, as Chancellor of the Exchequer, and by Winston Churchill, President of the Board of Trade, both of whom insisted that four would be enough.

Despite a campaign by elements of the press and by the Navy League for eight, the Admiralty rested on its calculations. At that point, of the seven battleships and two battle cruisers laid down by Germany, none was complete. Moreover the widening of the Kiel Canal, vital to allow the easy passage from the bases and exercise areas of the Baltic, was at an early stage and Germany’s North Sea defences were inadequate. Nevertheless, the fear that a crisis might draw away some of the battle fleet persisted, and was given more immediacy by the Bosnian annexation dispute between Austria-Hungary and Russia, and by the Casablanca incident involving Germany and France, both of which occurred in 1908.

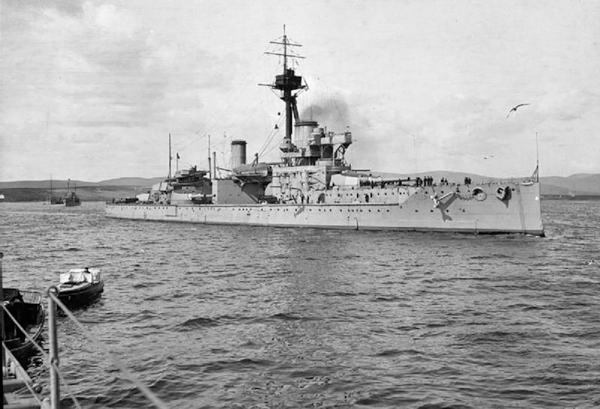

HMS Hercules.

HMS Hercules at Scapa Flow.

By early 1909 Britain had seven dreadnoughts in commission, with five building. Though Germany as yet had none in service, she had ten building, to be ready by 1912, and with her plans to build four a year, she would soon be ahead of Britain. Fears began to grow, based on the calculation that Krupps had the capacity to arm eight dreadnoughts a year.

The newspaper cry went up ‘We want eight, and we won’t wait’, with both The Times and the Daily Telegraph joining in the campaign. An article in the Observer demanded ‘the eight, the whole eight and nothing but the eight’ and eventually the Cabinet offered a compromise. Four ships were to be included in the 1909–10 programme, with the provision for four more to be included by April 1910 ‘if it appeared necessary’. This was on the understanding that these would be additional ships ‘without prejudice to the 1910–11 programme’ rather than the anticipation of the next year’s plans. The ships were all to be completed by 1912, so restoring the Royal Navy’s precarious advantage. Churchill was to write of this decision: ‘a curious and characteristic decision was reached. The Admiralty had demanded six ships, the Treasury offered four, and we eventually compromised on eight.’

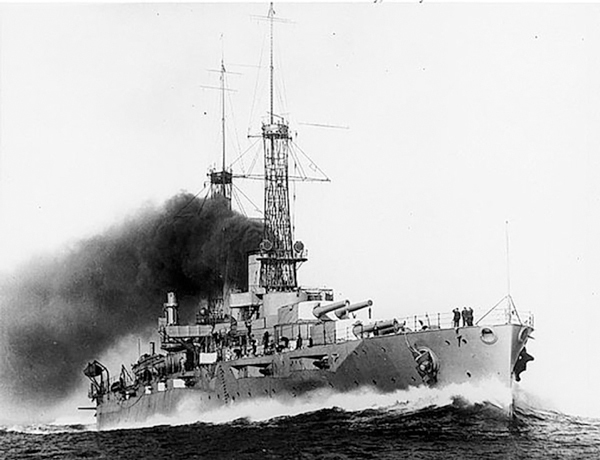

HMS Lion.

SMS Goeben.

Provided for in the 1909–10 Estimates were the two 20,000 ton halfsisters to Neptune, named Colossus and Hercules. These retained the unusual layout of the main armament which had characterised the earlier ship, but the four Orions showed two significant changes. They disposed all ten guns of the main armament in five centre-line turrets, in two super firing pairs fore and aft with one turret amidships. This layout meant an increase in displacement of 22,500 tons; moreover the guns were of 13.5-inch calibre, firing a shell of 1,250 pounds against the 850 of the 12-inch gun. The same calibre gun was mounted in the two ships of the eight gun battle cruisers which completed the programme. These were Lion and Princess Royal, of 26,500 tons and capable of 27 knots.

HMS Indefatigable.

To complete the advantage were two ships which did not feature in the British naval estimates at all. The battle cruisers Australia and New Zealand, sister ships to the Indefatigable were laid down in June 1910. On completion in 1912, New Zealand was placed at the disposal of the Admiralty. Australia was stationed in the Pacific at the outbreak of war, but joined the Grand Fleet in 1915.

Germany maintained her programme of four ships a year. In 1909– 10 these included the fourth of the Helgolands, named Oldenburg and the battle cruiser Goeben. The others were Kaiser and Friedrich der Grosse, of 25,000 tons. Each mounted ten 12-inch guns in a pattern very similar to Neptune, with offset beam turrets. Three further ships of this class, together with the battle cruiser Seydlitz, followed in the 1910–11 programme. Britain countered these with the four King George Vs and the battle cruiser Queen Mary, all with 13.5-inch guns. All of these ships were complete by the end of 1913, to widen the gap in Britain’s favour. She then had eighteen dreadnought battleships and nine battle cruisers (if we include Australia and New Zealand) against Germany’s thirteen and four. This was not a two-power standard; by then the aim was for a margin of sixty per cent superiority over Germany.

Other countries were being discounted in the calculations. France was linked with Britain by the 1904 Entente and the 1913 Naval Agreement arranged for a concentration of her naval strength in the Mediterranean. In 1912 France could deploy fourteen pre-dreadnoughts and the six ‘semi-dreadnoughts’ of the Danton class at Toulon and Oran to counter the eight old battleships of Italy and the nine of Austria-Hungary. Although these countries were both members, with Germany, of the Triple Alliance, disputes over the ownership of Italia Irredenta – the Tyrol, Trentino and Istria – meant that their naval building was directed at least as much against each other as against any foreign enemy. Moreover, mutual recognition of colonial claims in Libya and Morocco respectively had eased Franco-Italian relations, and Italy had always said that she would not engage in war with Britain.

Italian dreadnought Dante Alighieri.

All three countries had begun to build dreadnoughts, but progress was slow and the first ships were not ready until shortly before the outbreak of war. By August 1914, France has commissioned the four Courbets which had taken three years to build. Of 23,500 tons displacement, they were capable of only 20 knots; armed with twelve 12-inch guns, four of which were mounted in wing turrets, they were seriously weaker than any contemporary. Their successors, Bretagne, Lorraine and Provence were basically similar to the Orions with a centre-line armament and guns of 13.4-inch calibre. They too were somewhat under-armoured, and they did not enter service until 1915–16.

Italian dreadnought Leonardo da Vinci.

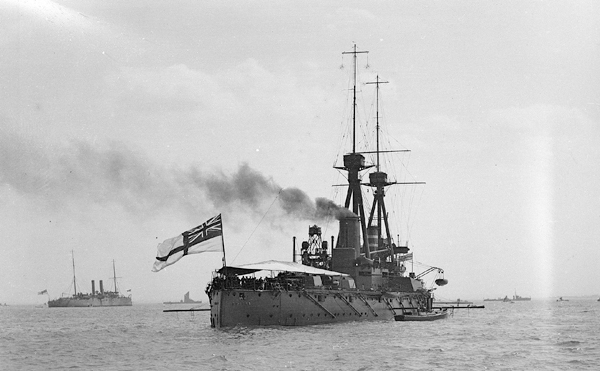

HMS Superb, 1907, pictured shortly after completion.

Italy’s first dreadnought, Dante Alighieri, was designed by Cuniberti, but showed significant alterations to his original design of 1903. The twelve guns of the main 12-inch battery were mounted in four triple turrets, all on the centre-line, and there was a secondary battery of twenty 4.7-inch, of which eight were in paired turrets abreast of A and D turrets. Like most Italian warships, before and since, she was capable of high speed, reaching 24 knots on her acceptance trials in 1913. A development of this design was seen in the three larger vessels of the Cavour class, laid down in 1910. The principle of centre-line armament and the triple turret were retained, but in place of the two turrets mounted amidships, the Cavours had only one. Two paired turrets were mounted to fire over the forward and aft turrets, to give the unusual total of thirteen big guns in five turrets. The secondary armament was mounted in casemates at upper deck level, and again the ships were rather lacking in defensive armour to gain another knot or two in speed. Giulio Cesare was commissioned in 1914, Conti di Cavour and Leonardo da Vinci in 1915, but the latter was lost when she blew up at her moorings in harbour at Taranto in August 1916.

Japanese Kongo class battle-cruiser Haruna (as rebuilt).

USS New York.

HMS Superb anchored in the Thames Estury, 1909.

The first Austrian dreadnoughts were also to be the last. The four ships of the Tegetthoff class were designed in 1910 to carry twelve 12-inch on a displacement of 20,000 tons. With the main armament in four triple turrets, B and C mounted to fire over A and D, they were an economical and effective design. The first three were in service by 1914 and were based at Pola throughout the war, but Szent István was built in the Danubius yard at Fiume, a political decision to gain the support of the Hungarian delegates in the Assembly of the Dual Monarchy when the estimates were approved. She was the first battleship to be built there and took almost four years to complete.

Russia too adopted the triple turret for her dreadnoughts. Although none of the four Ganguts was ready at the outbreak of war, all were in service by December 1914. They had been authorised in 1907 and laid down in 1909, but their building had taken so long that they were virtually obsolescent by the time they were completed. They had two turrets amidships, restricting end-on fire to only three guns ahead or astern. They were assigned to the Baltic Fleet, and the succeeding Imperatrica Maria, Imperator Aleksander III and Ekaterina II to the Black Sea. They broadly resembled the earlier ships, but were two knots slower, while a fourth, to be known as Imperator Nikolaj I was to have mounted eight 16-inch guns, but was never completed.

HMS Glatton circa 1914.

Spain built three small dreadnoughts at Ferrol between 1909 and 1915, each of 15,700 tons and mounting eight 12-inch guns. The smallest dreadnoughts ever built, each was armed with eight 12-inch guns provided by Armstrongs and powered by turbines produced by Parsons. Greece was the only other European country to contemplate owning dreadnoughts, and Salamis was laid down at the Vulkan yard in Hamburg, but was never completed.

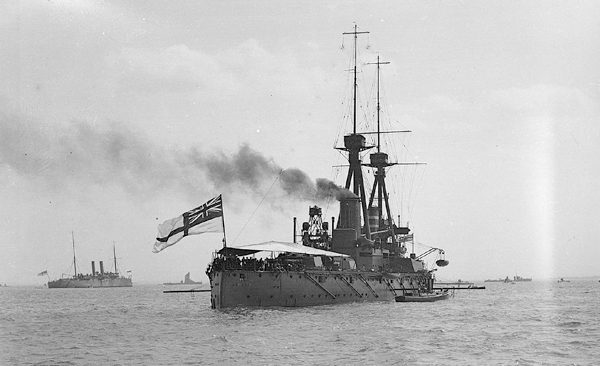

Battleship HMS Temeraire at anchor at Spithead. (© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London)

Japan and America were, of course, the other two naval powers of significance. By 1906 Japan was building her own warships, and Aki and Satsuma, though conceived as dreadnoughts, were actually completed with a mixed heavy armament. Kawachi and Settsu, with twelve 12-inch guns (of two different types), were commissioned in 1912 and the next two, Fuso and Yamashiro mounted twelve 14-inch in six twin turrets. Four early battle cruisers (Tsukuba, Ikoma, Ibuki and Kurama) were each armed with four 12-inch before the battle cruiser Kongo became the last Japanese vessel to be built in England, by Vickers at Barrow-in-Furness. Of 27,500 tons, she carried eight 14-inch guns and could raise 27.5 knots, and three sisters (Hiei, Haruna and Kirishima) were then built to the same design in Japanese yard.

The United States laid down two battleships each year from 1906, with increasing tonnage and calibre of guns, so that New York and Texas, which joined the Atlantic Fleet in 1914, mounted ten 14-inch guns on 27,000 tons.

She now had ten dreadnoughts in service, with four more building; all featured the lattice masts which were so distinctive of Americanbuilt ships. The USA was now clearly the world’s third naval power, behind Britain and Germany, but ahead of the emergent Japan and well ahead of the declining naval strength of France or Russia.

With Japan as an ally, with France and Russia members of the 1907 Triple Entente, and with no likelihood of hostilities with the USA, it was only Germany which presented any threat to Britain. She had laid down three battleships of the König class, but was still arming her ships with 12-inch guns. Britain countered with the four Iron Dukes, and the battle cruiser Tiger (ten and eight 13.5-inch respectively. These were the last ships completed by the end of 1914 and Britain had more ships building than had Germany. The advantage in the naval race had gone very clearly to Britain.