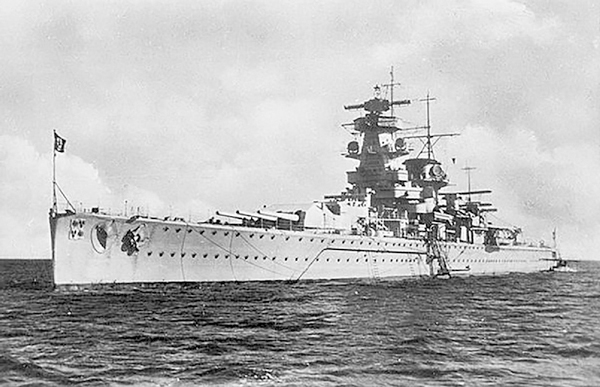

Japanese battle-cruiser Kongo.

T he reduced battle fleets could not be augmented in numbers, but two significant developments followed from the Washington treaty. The first of these has already been covered – the conversion of some of the cancelled ships into aircraft carriers. Although the dispute over the relative merits of the big gun and naval aircraft had yet to be resolved, the commissioning of carriers into the major navies had begun. This led inevitably to the perception of the need to provide battleships with the means to survive an air attack. Anti-aircraft armament was added to other improvements, including the conversion of coal-burning vessels to oil fuel, improved protection and the provision of catapult-launched spotter aircraft, all of which combined to make the older ships vastly more effective. In some cases the result was a complete transformation of a ship which had served throughout the First World War, into an essential unit of the battle fleet in the second.

Nowhere was this done more thoroughly than in Japan. The ships which she had been allowed to retain had to be of maximum effectiveness and the work done on the four Kongo class amounted to little short of a complete rebuild. During two periods of conversion they were transformed from 1914 battle cruisers into fast battleships well-suited to the role of escorts to the carrier strike force. Among other modifications, the total weight of armour was increased from 6,500 tons to over 10,000 tons, and the ships were completely reengined. They were also given the ‘pagoda’ bridge which became so characteristic of Japanese battleships and had two funnels in place of the original three.

Japanese battle-cruiser Kongo.

The four old battleships were given similar, if less extensive, treatment, and even the two Nagato class were refitted. In particular the elevation of their 16-inch guns was increased from 30 to 43 degrees for added range. All the ships were converted from coal to oil, increasing their efficiency, but also increasing their country’s dependence on external oil supplies.

In America one outward sign of refit was the replacement of the familiar lattice masts by those of a more conventional pattern. Here too the conversion to oil fuel from coal, and the reduction in the number of funnels from two to one gave the ships a more modern profile. This was repeated in the Royal Navy’s Queen Elizabeth class whose two funnels were trunked into one during the 20s. Repulse and Renown were given improved armour and, in the case of Renown, an anti-torpedo bulge and a tower bridge of the type introduced into Nelson. In all the ships the anti-aircraft armament was increased, but in all it was found to be inadequate to the needs of combat. After 1939 further installation of 20mm and 40mm weapons had to be made. The Revenge class vessels were less substantially modified and HMS Hood, due for refit in 1939, could not be spared when war came for the essential work to be carried out.

Battlecruiser HMS Renown in 1945 alongside at Devonport. (© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London)

The first significant new building came in Germany, in a class of ships nominally within the treaty limits, but alarming in their size and hitting-power. These were the three armoured cruisers, known as Panzerschiffen in Germany, but revered elsewhere as ‘pocket battleships’ of the Deutschland class. Designated as the legitimate replacements for the three Braunschweig class, then serving as coast defence and depot ships, they were supposedly within the treaty limits of 10,000 tons displacement, made possible by the use of electric arc welding as opposed to traditional riveted plates. Although this method did save some fifteen per cent of the weight of the hull alone, they nevertheless exceeded the limit by 1,700 tons (3,000 tons at full load). Their armour was designed to give protection against the 8-inch guns permitted to cruisers under the Washington Treaty, while their diesel engines gave them an extensive radius of action and a speed of 28 knots. This was faster than any capital ship save the three British battle cruisers and the four Japanese Kongo class. Armed with six 11-inch guns in two triple turrets, they were more powerful than any cruiser, and seemed ideal as commerce raiders – they could outgun almost any vessel which could catch them.

The first Deutschland was ordered in 1928 and laid down in February 1929, under the Chancellorship of Gustav Stresemann, and the other two, Admiral Scheer and Admiral Graf Spee, were laid down in 1931–32 in the dying years of the Weimar Republic. By the time the first was commissioned in April 1933, Adolf Hitler had become Chancellor of Germany.

Panzerschiff Admiral Graf Spee.

France and Italy, their eyes on one another as well as on Germany, both began to rearm. The 1930 London Naval Agreement extended the ‘battleship holiday’ to 1936, and retained the Washington limitations on displacement and armament, but neither France nor Italy was a signatory.

France needed new ships to replace the aging Danton class which were still in service in a limited role. She had lost one of her seven dreadnoughts when France ran aground in 1923. The building of Deutschland intensified her need and in 1932 work began on a battle cruiser of 26,500 tons and 30 knots. Dunkerque embodied one of the innovations which had been planned for the cancelled Normandie class and Lyon class, as her eight 13-inch guns were mounted in two quadruple turrets, both mounted forward of the bridge. They were more widely separated than those of the Royal Navy Nelson class, to reduce the chance of both turrets being put out of action by a single hit. The arc of fire was severely limited, as it was found impracticable to use the main armament more than a few degrees aft of the beam, and the light construction of the ship made her vulnerable to damage from the recoil of the guns. With twelve of the sixteen guns of the dual-purpose secondary armament also in quadruple mountings, and with a large aircraft hangar and crane aft, Dunkerque and her sister Strasbourg clearly belonged to a new generation of capital ships; the layout was retained in the next class of French ships.

Strasbourg was laid down in 1934, by which time Germany was building the two later Deutschland class, Admiral Scheer and Admiral Graf Spee. In the same year Italy laid down two new fast battleships. She too had only four battleships in service; attempts to salvage and refit the wreck of Leonardo da Vinci which had been sunk in 1916 by a magazine explosion, having been abandoned and Dante Alighieri having been scrapped. Littorio and Vittorio Veneto were nominally of 35,000 tons, but displaced some 6,000 tons more, and were armed with nine 15-inch guns in triple mountings. Capable of 31 knots, they incorporated improvements to armour and anti-torpedo protection.

French battle-cruiser Dunkerque.

France countered these by laying down two 35,000 ton ships of the Richelieu class, whereupon Italy began two more of the Littorio class. A new naval race was under way. Britain had proposed a further conference to restrict naval building: it met in London in 1935, but to little effect. The limit of 35,000 tons for battleships was ratified yet again, though the Italians were far exceeding it already, and an attempt to restrict the calibre of guns to 14-inch proved a failure. Both France and Italy were already building ships armed with 15-inch guns, while the Americans retained the 16-inch and the Japanese went to 18.1-inch for the Yamato class battleships.

French battle-cruiser Strasbourg.

Italian battleship Littorio.

Vittorio Veneto at Matapan.

Italy began a very extensive modernisation of her four old battleships. This included the removal of the midships triple turret, enabling the installation of more powerful engines giving a speed of 27 knots, but protective armour, though improved, remained inadequate. The Italian fleet was developing in a way which caused no little concern to France and Britain after 1935. While Mussolini had been looked upon as an associate during the brief existence of the Stresa Front, (an agreement between the Italian Fascist dictator, and the French and British prime ministers), this concern had not been acute. However, the Italian invasion of Abyssinia revealed Mussolini’s imperial ambitions; his new fleet was clearly intended to make the Mediterranean his longed for ‘Mare Nostrum’. The involvement of both Mussolini and Hitler in active support for the Nationalist side during the Spanish Civil War, and the formation of the Rome-Berlin Axis, placed the two dictators firmly on the same side.

German battle-cruiser Scharnhorst.

German battle-cruiser Gneisenau.

Soon after coming to power in 1933, Hitler was determined to rebuild the German navy as an effective fighting force and he was disposed to listen to the request made to him by Admiral Raedar for the next two of the Panzerschiff programme to be better-protected and more heavily armed. An initial increase in displacement to 19,000 tons was agreed, but this was soon increased to 26,000, and Scharnhorst and Gneisenau exceeded even this by a further 6,000 tons. A third triple turret was added, but the calibre of gun remained 11-inch. This was an expedient to enable more rapid completion of the ships, using the six turrets built for the three further Deutschland class, but it left the two ships under-armed by comparison with their contemporaries in any navy. It was planned to replace the 11-inch turrets with 15-inch, when the German armament industry was again in full production, but this was never carried out. Nevertheless, the two ships were to be a serious threat to Britain’s trade routes.

Britain’s response to the renewed German naval building was the agreement that Germany could build up to thirty-five per cent of the Royal Navy’s strength in surface ships with parity in submarines. The assumption that a freely-negotiated agreement would have a more binding effect than the imposition of a clearly unenforceable disarmed state gave Hitler and his admirals as much scope as they needed for the moment.

German battleship Bismarck.

As Britain had fifteen capital ships in commission in 1935, Germany could build five, of which the Scharnhorst class included the first two. The next two were to follow quickly: the 15-inch Bismarck and Tirpitz were ordered in 1935 and 1936, and both were laid down in the latter year. Nominally of 35,000 tons, they displaced 41,700 and 42,900 respectively on completion. By then the maximum tonnage for battleships had risen to 45,000 tons by an agreement signed in 1938. They were powered by conventional turbines, giving a maximum speed of 29 knots, rather than by the diesels of the Deutschland class or the turbo-electric motors originally planned for them, and they were as well protected as any of the last generation of battleships.

They were the last two battleships to be built by Germany, though two more were laid down in 1939 out of six proposed by the Z Plan, by which, as in the early years of the century, Germany sought to attain parity with Britain. These were to be 55,000 ton ships armed with eight 16-inch guns – some of the guns were built and used in coastal batteries in Norway and on the Channel coast, but the ships were abandoned. The accompanying project for three 15-inch 35,000 ton battle cruisers never reached fruition, nor did a series of further battleship plans coded H41 to H44.

In face of this renewed challenge to Britain’s overseas trade routes, the Admiralty prepared to begin building modern battleships in 1935. The 35,000 ton limit was still in force, and a proposal to limit the calibre of big guns to 14-inch was being canvassed, so that these were the specification for the five ships of the King George V class, the first two of which were authorised in 1936. In that year the London Naval Agreement did limit the calibre to 14-inch, but with the proviso that this would not be binding on the signatories if Japan failed to ratify the treaty by April 1937. Not only did Japan refuse to sign, she had embarked on the 18-inch Yamato class, but Britain was committed to the 14-inch gun. The original intention had been to mount twelve of these in three quadruple turrets, but in the event, the number of barrels was reduced to ten by substituting a twin turret for the second forward quadruple mounting in order to save weight. This delayed the completion of the ships while the new turret was designed and problems over the complex quadruple turrets also postponed production. King George V joined the fleet in December 1940, Prince of Wales and Duke of York in 1941, and Anson and Howe in 1942. They displaced 38,000 tons in the final design, with 12,000 tons of armour and could raise 29 knots. A secondary armament of sixteen 5.25-inch dual-purpose guns, and between thirty-two and seventy-two 40mm Oerlikons showed the awareness of the need to provide for adequate defence against air attack.

HMS King George V.

USS South Dakota.

USS Missouri.

A design for four Lion class battleships of 40,000 tons was prepared and two keels were laid down, but construction work was abandoned when it became apparent that the need for cruisers, escorts and carriers was more urgent. One further battleship was built during the war, the 44,500 ton Vanguard armed with the four 15-inch twin turrets removed from Courageous and Glorious on their conversion to aircraft carriers, but she was not commissioned until 1946.

In 1937 the Americans began their new battleship construction programme with the two North Carolina class. It had originally been intended that these should mount twelve 14-inch guns in quadruple turrets, but the failure of the Japanese to ratify the London treaty led to a change to nine 16-inch instead, in three triple turrets. As the displacement limit had been observed, a speed of 28 knots was all that could be managed without sacrificing armour. Four South Dakota class of similar size and armament were authorised by Congress in 1939 and the final design was for six Iowa class, of 48,000 tons with nine 16-inch guns and capable of 33 knots.

Japanese battleship Yamato.

Four of these joined the fleet in 1943–4, with the other two being cancelled, as were the succeeding five ships of the Montana class (60,500 tons and twelve 16-inch). Two ships of the Alaska class, completed in 1944, are variously described as large cruisers of 30,000 tons, or as battle cruisers, because of their armament of nine 12-inch. As neither saw action, and as both were laid up immediately after the war ended, the question is academic.

Under conditions of great secrecy, with the building concealed by sisal curtains, Japan built the ultimate in battleships, Yamato and Musashi of 65,000 tons and armed with nine 18.1-inch guns – a huge tender being built to carry the immense gun barrels from the ordnance factory to the dockyard for installation. A third, Shinano, was completed as an aircraft carrier and a fourth cancelled.