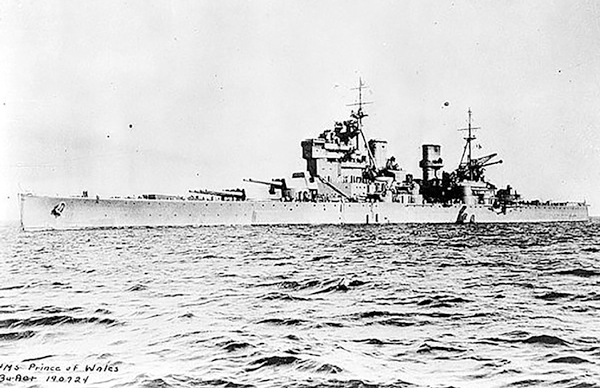

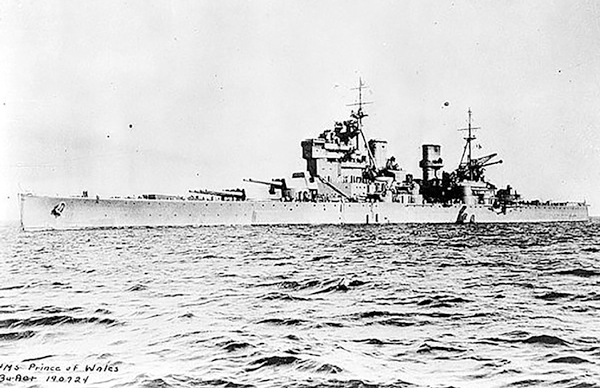

HMS Prince of Wales.

W hen Britain and France responded to Germany’s attack on Poland in September 1939 by declaring war, they had no way of intervening directly by land or air, and the period known as the Phoney War began. The war at sea, however, began from the first day and here the Allies had a degree of superiority even greater than in 1914. Germany had in commission only Scharnhorst, Gneisenau and the three pocket battleships. The Royal Navy, by contrast, had fifteen capital ships, though the latest refitting of Queen Elizabeth and Valiant was not quite complete. Twelve of the ships were, however, of First World War vintage despite some modernization. The most modern were the two Nelson class, already in service for twelve years. France had six old dreadnoughts and the two Dunkerque class in commission. These could be stationed in the Mediterranean against any possible threat from Hitler’s ally Mussolini. Although the Pact of Steel, signed six months earlier in May 1939, had changed the Rome–Berlin Axis into a military alliance, Italy was unprepared for war and for the time being remained neutral.

The only naval strategy open to Germany was the classic recourse of the weaker power, the ‘guerre de course’. In anticipation of the opening of hostilities, Deutschland and Admiral Graf Spee were already at sea in August 1939 and were able to strike at the Atlantic trade routes. Deutschland sank only two ships of 6,000 tons before her recall, when she was renamed Lützow, lest the loss of a ship named after the Fatherland should have adverse propaganda value.

Admiral Graf Spee had more success in the South Atlantic and in a brief foray into the Indian Ocean. Here ships were sailing independently and the raider picked off nine, with an aggregate of 50,000 tons. Her captain, Hans Wilhelm Langsdorff, scrupulously observed the rules of cruiser warfare: her victims were stopped by warning shots and their crews taken off before the vessels were sunk. The captains and first engineers were kept aboard Graf Spee while the remaining crew members were transferred to the raider’s supply ship, Altmark from which they were eventually released (in Norwegian waters) by the destroyer HMS Cossack.

No fewer than eight different hunting groups were employed in the search for the German raider, including the battle cruiser HMS Renown and the French ships, Strasbourg and Dunkerque, all of which were faster and more heavily armoured than the Graf Spee. Also, there were two carriers and fourteen cruisers assigned to the task. It was Commodore Henry Harwood’s three cruisers of Force G which eventually intercepted Graf Spee off the estuary of the River Plate and there followed a running battle. The 11-inch guns of the raider gave her a total weight of broadside double that of her opponents, but they were mounted in two turrets and she had three opponents, which attacked her from different quarters.

By concentrating her fire on the 8-inch gunned cruiser Exeter she was able to put out of action the most powerful of the British vessels in Force G, but sustained damage and lacked the speed to escape. Pursued by the 6-inch gunned cruisers, Ajax and Achilles, (the latter a ship of the New Zealand navy), Graf Spee took refuge in the neutral port of Montevideo, capital of Uruguay.

Intense naval and diplomatic activity followed Captain Langsdorff’s request for time to be allowed for the repair of his ship. While British opposition to the completion of any but essential repairs outwardly suggested the desire for the warship to put to sea again as soon as possible, the sailing of a series of British merchant vessels was arranged to delay her departure. International law decreed that twenty-four hours had to elapse between the sailings of ships of rival belligerents from a neutral port. Meanwhile, the damaged Exeter had been ordered back to the Falkland Islands to be replaced by the 8-inch gunned HMS Cumberland. It would be some days before more substantial help could arrive. The faulty intelligence that Renown and the carrier Ark Royal had reinforced the waiting cruisers was enough to convince the Germans that it would not be possible for Graf Spee to return to Germany and she was scuttled in the estuary of the Plate.

If the first blood had been gained by Britain, the German surface raiders now had success. The Admiral Scheer attacked the convoy HX 84, escorted only by the armed merchant cruiser HMS Jervis Bay. The auxiliary cruiser bravely engaged the German warship, enabling the convoy to scatter, so that all but six of the merchantmen escaped.

In all Admiral Scheer sank seventeen victims, totalling 113,000 tons in five months at large, before returning to Kiel. Neither she nor Lützow were again to menace the Atlantic routes. Scharnhorst had also sunk an armed merchant cruiser, the P&O liner Rawalpindi on patrol off Iceland in 1939. In February 1941 she sailed with Gneisenau on a cruise commanded by Admiral Günther Lütjens, which led to the destruction of twenty-two ships, a total of 115,000 tons. That this was not larger was due to the Admiralty policy of using battleships as escorts to convoys. The German raiders three times encountered convoys escorted by capital ships and each time they refused to risk damage in action with a more heavily-armed, if slower opponent.

In February 1941 they came upon convoy HX 106, escorted by HMS Ramillies, and in March they fell in with a Sierra Leone convoy, escorted by another 15-inch battleship, HMS Malaya. Similarly they found convoy SL 67 protected by the 16-inch HMS Rodney. The old, unmodernised battleships of the Revenge class were ideally suited to this work, where their lack of speed was of little disadvantage and where their 15-inch guns could deliver the kind of blow which no raider could risk taking. The destruction of the raider would be the ideal outcome, but not the sole aim: serious damage would be enough to put an end to her depredations. HMS Ramillies had already escorted troop convoys to France in 1939, Resolution and Revenge had protected transatlantic convoys carrying Canadian troops to England, while Malaya protected convoys with reinforcements for the Eighth Army in North Africa, via the Cape of Good Hope. Similar duties fell to Nelson and Rodney in 1942, and to the battle cruisers Repulse and Hood, which had the added advantage of speed.

The crucial point in the threat by surface raiders on the shipping lanes came in May 1942. The newly-completed Bismarck, accompanied by the 8-inch heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen and again commanded by Admiral Lütjens, was ordered into the Atlantic. The two ships had first been identified as they passed through the Kattegat, off Denmark, and were then spotted by RAF reconnaissance aircraft in Korsfjord, Norway. The Norwegian resistance and Fleet Air Arm reconnaissance then showed them to have sailed and Admiral Tovey deployed all units of the Home Fleet to cover possible routes into the Atlantic. The least likely was that to the north of Scotland, which could be watched from Scapa Flow, where a scouting force of four light cruisers was backed by King George V and Repulse, together with the carrier Victorious. The passage between the Faroes and Iceland was also covered by three cruisers, with HMS Prince of Wales and HMS Hood off Iceland. The most distant, and the likeliest route for Lütjens to choose, was the Denmark Strait between Iceland and Greenland where the 8-inch cruisers Norfolk and Suffolk were on patrol.

It was in the Denmark Strait that Suffolk sighted the German ships, keeping them under observation by radar while she was joined by Norfolk, and then by Hood and Prince of Wales. Soon after dawn on 24 May, Hood opened fire on the leading German vessel Prinz Eugen, while Prince of Wales correctly identified Bismarck and also opened fire. The British ships, approaching at a shallow angle, could only use their forward turrets. The range was closing slowly when both German ships targeted Hood. It is now thought by some that an 8-inch shell from Prinz Eugen hit the lightly protected 4-inch guns magazine and the explosion penetrated to the main 15-inch magazine. Hood was destroyed as suddenly as her predecessors had been at Jutland. Only three members of the crew survived; 1,415 men on board lost their lives.

The newly-commissioned Prince of Wales, already experiencing trouble with B turret, was now the target for both German ships, had five of her ten 14-inch guns put out of action. She was also severely hit as she turned away to break off the engagement.

She had, however, caused damage to Bismarck leading to a leak of oil fuel and seawater contamination to her fuel tanks. This damage combined to lead Lütjens to decide that he must abandon the enterprise, and make for Brest, where there was a dry dock capable of taking a ship the size of Bismarck to enable repairs to be made. Prinz Eugen was detached to make her own way to safety, while Prince of Wales remained in support of the covering cruisers. Admiral Sir John ‘Jack’ Tovey left Scapa Flow with his main force, at the same time detaching other ships to join the hunt – these included Rodney, Ramillies and Revenge as well as Force H from Gibraltar. An attack by Swordfish torpedo bombers from Victorious scored one hit, but failed to stop the battleship which then contrived to elude the shadowing cruisers during the night. A sighting by a Catalina of RAF Coastal Command regained contact, and another strike from Ark Royal’s Swordfish succeeded in achieving two torpedo hits. One, amidships, caused little damage, but the second hit the rudder and made the ship unmanoeuverable. Bismarck survived determined destroyer attacks during the night, but King George V and Rodney were within range at dawn and she was first crippled by gunfire, and a torpedo hit from Rodney (an event unique in the age of the battleship) and then sunk by a torpedo by the cruiser Dorsetshire. Even then her surviving crew member claimed that she had been scuttled, giving rise to claims that she and her sister were unsinkable.

HMS Prince of Wales.

Whatever the truth of such assertions, and despite the blow she had struck by the sinking of Hood, the inescapable fact was that Bismarck was gone, and with her the threat from surface ships to the Atlantic trade routes. This was only the first stage of the battle of the Atlantic, but from this point it was to be the submarine which posed the main threat, and it was the escort group – destroyers, corvettes and eventually the escort carrier and long-range aircraft – which was to combat that threat. Battleships were to be deployed less frequently in the Atlantic, though in August 1941 Prince of Wales took Mr Churchill to Newfoundland for a meeting with President Roosevelt, escorting a convoy home, while Duke of York’s first operation was also as escort to a convoy in December of that year. By that time, the Americans were mounting Neutrality Patrols which involved Texas, New York and Arkansas, while after her entry into the war, Mississippi, New Mexico and Idaho were also employed as escorts.

Prinz Eugen had successfully evaded the British ships after parting company from Bismarck and had joined Scharnhorst and Gneisenau in Brest. There the air attacks, which had already inflicted enough damage to prevent the battle cruisers from joining Bismarck in her foray, continued. Eventually Admiral Otto Ciliax was ordered to risk the hazardous passage of the direct route through the Channel to bring the three ships back to the relative safety of a German port. This, aided by a series of accidents and the slow reaction of the British, he contrived to do. After fighting off successive attacks by motor torpedo boats, Swordfish torpedo bombers of the Fleet Air Arm, and Hudsons and Beauforts of the Royal Air Force, both Scharnhorst and Gneisenau struck mines off the Dutch coast. They reached the safety of Wilhelmshaven and Brunsbüttel respectively, but were in need of substantial repair. Gneisenau never put to sea again. Their presence, together with Lützow and Admiral Scheer as well as Tirpitz, threatened the Arctic supply convoys to Murmansk and Archangel which began in August 1941, following Hitler’s attack on the Soviet Union. It was therefore necessary for the Admiralty to retain two modern battleships and a carrier at Scapa Flow to counter this menace. They were supported in this task by USS Washington in 1942, and in the following year by the Alabama and South Dakota. The battleships were deployed as distant cover to the convoys, being kept to the west of the narrow channel between the north of Norway and the edge of the Arctic ice. Cruisers were employed as the main cover, with a close escort of destroyers, anti-aircraft ships and escort carriers.

An operation involving Tirpitz, Lützow, and Scheer was planned against convoy British convoy PQ17. The Admiralty ordered the escort to leave and the convoy to scatter. The surface threat did not materialise, but the merchantmen were defenceless against the onslaught of submarines and of aircraft flown from bases in Norway. It was a disaster, only ten of thirty-three merchantmen reached Murmansk. The battleships King George V and Washington were too far to the west to be involved. The same was true of Duke of York and Anson when PQ18 was attacked in September 1942.

The success of the escorting destroyers and cruisers, in driving off the attacks by Lützow and the 8-inch cruiser Admiral Hipper on the convoy JW51B in December 1942, had far-reaching effects. Hitler, infuriated by the failure, told Admiral Raedar of his ‘firm and unalterable resolve’ to decommission all the capital ships whose guns would be used to equip coastal batteries and whose crews would be redeployed. This precipitated Raeder’s resignation, and his replacement by Admiral Karl Dönitz, but the big ships were retained. Dönitz was able to convince Hitler that the work of breaking up the ships was too lengthy and involved too big a task for Germany to undertake at that stage of the war.

Scharnhorst and Tirpitz were the two most powerful of the German warships, and both became major targets for British forces. An assault on the great Normandie dock at St Nazaire had already been carried out to deny Tirpitz the one major repair yard which would have enabled her to operate in the Atlantic. Now that she was based in a Norwegian fjord, she was the object of a daring attack by midget submarines. Towed across the North Sea, three of these X-craft penetrated the net defences around the battleship; the explosions of the charges which they placed beneath her hull put her out of action for six months. She was therefore unable to accompany Scharnhorst on her attack on convoy JW55B and the returning RA55A in December 1943. Intercepted by the cruisers of Rear Admiral Sir Robert Burnett, Scharnhorst was brought within the range of the 14-inch guns of HMS Duke of York, and sunk off North Cape.

Tirpitz was the target of repeated air attacks, first by aircraft of the Fleet Air Arm and then by the Royal Air Force. Finally, in November 1944, she was overwhelmed by 12,000 pound Tallboy bombs dropped by Lancasters of 9 and 617 Squadrons. She capsized and sank in Tromso Fjord, never having fired her great guns in action.

HMS Duke of York.

Battleships had also been used in home waters in support of military operations. The German invasion of Norway in 1940 had seen the deployment of the two battle cruisers which were involved in action: HMS Renown along with the Gneisenau suffering damage, the latter being torpedoed by the submarine HMS Clyde. Scharnhorst sank the carrier HMS Glorious, but was then struck by a torpedo from the destroyer HMS Acasta. Both German ships were under repair for some months, along with Lützow, hit by coastal batteries and later torpedoed by the submarine HMS Spearfish. The heavy German cruiser Admiral Hipper also needed dockyard attention after her unequal duel with the destroyer Glowworm. The Germans also lost the 8-inch cruiser Blucher to coastal batteries, and two light cruisers: Königsberg to dive bombers of the Fleet Air Arm and Karlsruhe torpedoed by the submarine HMS Truant. Ten destroyers were sunk at Narvik, where HMS Warspite was in support during the second of the two battles.

This rendered the German navy virtually non-existent at the time of the hastily-prepared Operation Sealion, the projected invasion of Britain. While air superiority was the first requirement, which was, of course, never achieved, there would have been quite inadequate naval escort for any seaborne invasion force. Such an assault would have faced attack by Nelson, Rodney and Repulse from Scapa Flow, with Valiant, Barham, Resolution, and Renown at Gibraltar. How these would have fared against air attack in confined waters is imponderable, but certainly the success of such an invasion would not have been as assured as has often been suggested.

HMS Royal Oak. (© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London)

The British ships had not escaped unscathed in the first year of war. HMS Nelson had been mined off Scotland in December 1939 and did not rejoin the fleet until the following August. In the same month Barham was torpedoed by U-30 off the Clyde and was in dock until April 1940. Rodney had been hit by a bomb which failed to explode, and Malaya was torpedoed by U-106 off Cape Verde while escorting a convoy, but all of these survived. Less fortunate was Royal Oak, torpedoed and sunk at her mooring in Scapa Flow by U-47. An old and unmodernised ship, she was of limited value, but her destruction and the loss of over 800 crew in what was thought to be a secure anchorage, was a blow to morale. Two of her 15-inch turrets were salvaged and were used to arm the monitors Abercrombie and Roberts, designed for coastal bombardment.

The surviving German pre-dreadnoughts Schliessen and Schleswig-Holstein had bombarded the Polish port of Gdansk in the opening days of the war, while Lützow and Scheer shelled Soviet positions in the campaigns of 1944–5. All four of these ships, together with Gneisenau, were heavily damaged by air attacks in the closing months of the war, and sank in shallow waters. By the time of Hitler’s death his battle fleet had ceased to exist.

The Allies were able to deploy units of their battle fleets in support of the Normandy landings and subsequent operations. Warspite, Rodney, Nelson, Ramillies, together with USS Arkansas, Texas and Nevada were part of Operation Neptune, the naval operation on D-Day, while Malaya saw her final action off St Malo in December 1944. With the balance in the war at sea, it now proved possible to send the more modern ships out to the Pacific, to lay up Revenge and Resolution and to lend Royal Sovereign to Russia. Renamed Archangelsk, she served with the Soviet navy until 1949. Of the two old French battleships interned in English ports during the war, Paris had been an accommodation ship at Plymouth, while Courbet was sunk along with the old target ship Centurion as part of the breakwater for the Mulberry Harbour.