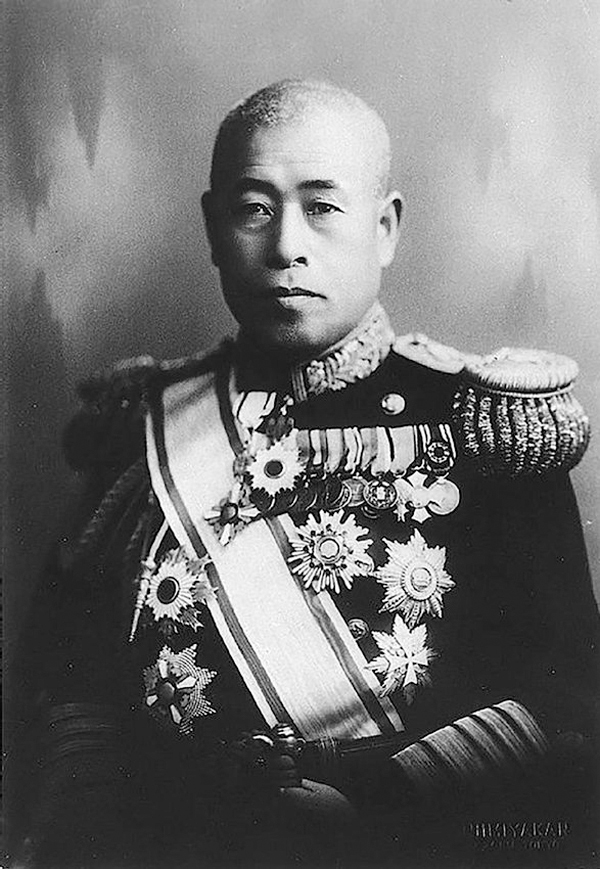

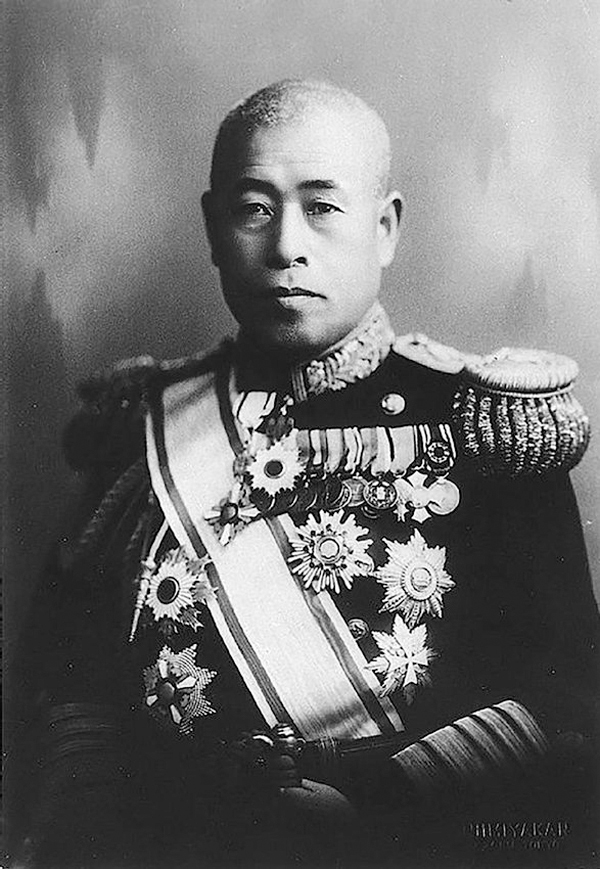

Admiral Yamamoto.

I n European waters aircraft had already massively affected the war and would continue to do so. Air reconnaissance had revealed the location of Bismarck after the shadowing cruisers had lost contact and an air strike had slowed her so that the encircling surface vessels could close and sink her. Eventually her sister ship Tirpitz was to be crippled and then sunk by land-based Lancaster bombers. But it was in the Mediterranean that the blueprint for carrier-based strikes was to be revealed. The crippling of three Italian battleships in their defended base at Taranto, by a handful of obsolescent and slow Swordfish torpedo bombers, was an object lesson in the effective use of naval air power, which would be particularly significant in the vast spaces of the Pacific.

The Japanese, limited in battleship strength by the Washington Treaties, had begun to create a carrier force with purpose-built aircraft and to devise a new strategy for its use. It was to alter radically the war in this theatre, where the vast distances involved meant the there was no possibility that land-based air power alone could determine events. Both America and Japan had given attention to the building of carriers and to the development of a separate naval air service, though the Japanese had a far clearer idea of how they would make use of the weapon. In the US Navy there was still a powerful battleship lobby and some distrust of the claims of naval aviation.

The original experimental carriers USS Langley and the Japanese Hosho were given support roles as an aircraft transport and a training ship respectively, but each navy had seven fleet carriers in commission in December 1941, with more under construction. After the conversion of Lexington and Saratoga, the Americans had built two smaller carriers, Ranger and Wasp in the 1930s, and three ships of the Yorktown class between 1937 and 1941. Eleven more (the Essex class) were on order, but the first of these was not in commission until late 1942. To their early conversions of Akagi and Kaga the Japanese had added the small Ryujo in 1933; while Hiryu and Soryu joined the fleet in 1939 and Shokaku and Zuikaku by 1941. Further Japanese building was for the conversion of liners, oilers and tenders, eight in all, so that they would quickly fall behind the Americans.

Admiral Yamamoto.

In 1941, the American Pacific Fleet, based at Pearl Harbor in the Hawaiian Islands, had eight battleships on its strength, as well as three fleet carriers. The Japanese Admiral Yamamoto had devised a plan of a surprise air strike by a carrier task force, to knock out this fleet and gain the initiative in the Pacific.

He warned his government that the industrial might of the USA would lead to a recovery, but that he could hope to achieve mastery of the sea for a year or eighteen months. In December 1941, therefore, a task force comprising six fleet carriers, escorted by the battleships Kirishima and Hiei, with three cruisers and nine destroyers, was clandestinely on its way. Meanwhile diplomatic activity indicated the steadily worsening relations between the two powers. Eventually problems with decoding delayed any formal declaration of war until after news of the attack had reached Washington, leading President Roosevelt to brand 7 December 1941 as ‘a day that will live in infamy’.

The aerial attack was timed for 8am on a Sunday morning with the fleet base in a peacetime mode, no hint of impending war having been received, though warning messages were on the way. Admiral Chuichi Nagumo, commanding the task force, dispatched an initial strike force of 140 aircraft (forty-nine bombers, fifty-one dive bombers and forty torpedo bombers) escorted by forty-three fighters, followed by a second wave of 171. Their targets, in order of priority, were the American carriers, then the battleships, the oil storage tanks and the aircraft at the three airfields. As it happened, the American carriers were not in harbour at the time of the attack, so that the battleships became the prime targets.

In the first attack, California, West Virginia, and Oklahoma suffered torpedo hits: Oklahoma capsized and sank, as did the old target ship Utah, torpedoed by the second wave of ‘Kate’ torpedo bombers, which also crippled Nevada. (‘Kate’ and ‘Val’ were Allied reporting names for the bombers.) In the subsequent attacks by ‘Val’ dive-bombers, Arizona blew up, and Maryland, Pennsylvania and Tennessee were all struck. All eight American battleships were therefore out of action for the immediate future, though only Arizona and Oklahoma were total losses. The other ships were repaired, and in some cases almost completely rebuilt, but it was months before any of them rejoined the fleet. Admiral Nagumo’s failure to launch a second strike, and destroy the machine shops and the oil tanks, meant that the victory was less complete than it might have been.

Having put the American battle fleet out of the reckoning, a further Japanese strike three days later accounted for the new British battleship Prince of Wales and the old battle cruiser Repulse. They should have been accompanied by the fleet carrier Formidable, but she had been damaged by grounding so, lacking effective air cover, they were discovered by Japanese land-based bombers off the coast of Malaya. First Prince of Wales was crippled, her steering wrecked and her antiaircraft turrets immobilised. Repulse was skilfully handled, avoiding both bombs and torpedoes from the first two strikes, but a third wellco-ordinated attack first damaged her steering, and three torpedo hits sank her.

HMS Repulse.

Prince of Wales, unable to defend herself, soon followed. At Pearl Harbor the American battleships had been stationary and not (so they thought) at war. Here were ships under way, their turrets manned, and yet they succumbed. It appeared that the argument, which had raged since General Mitchell’s aircraft had sunk the Ostfriesland, had now been settled.

A small American, British, Dutch and Australian cruiser force was next overwhelmed in the Java Sea and Japan controlled the Pacific, overrunning French Indo-China, the Dutch East Indies, the Philippines, Hong Kong, Singapore and Malaya, giving them resources including rice, oil and rubber to support their war effort. Their invasion forces, escorted by the four Kongo class battleships and by heavy cruisers, enabled them to pick their targets. By this time France and the Netherlands were already under German occupation and Britain fighting for survival; none could give much support to their far eastern assets.

The Japanese mastery of the Pacific turned out to be much more short-lived than Yamamoto had expected. The American carriers had been absent from Pearl Harbor, Saratoga on the Pacific coast, while Lexington and Enterprise had been delivering aircraft for the defence of Midway and Wake islands. Their survival meant that they were now the focal point of the fight back, with battleships reduced to escort duties and shore bombardment.

An American counter offensive began with the battle of the Coral Sea in early 1942. The Japanese attempt to extend their perimeter by taking Port Moresby in New Guinea and threatening a strike against Australia resulted in the first-ever naval action in which the opposing fleets never made contact, all the fighting being done by the aircrews. The Japanese appeared to hold every advantage, but superior American intelligence work had made known the enemy plans. The Japanese deployed the light cruiser Shoho, escorted by four heavy cruisers, with the fleet carriers Zuikaku and Shokaku, similarly escorted, providing distant support. Against this were deployed the American carrier Task Force 17, spearheaded by USS Yorktown and TF 16 (USS Lexington), with cruisers necessarily providing the escort. The Japanese admiral had devised an elaborate plan to trap the Americans between his two forces, but his calculations assumed only one US carrier. The ensuing battle was a tactical draw, with the sinking of Shoho and the loss of forty-five aircraft and of USS Lexington, (thirty-six aircraft lost) and heavy damage to the Shokaku, but a strategic victory in that it ended the period of Japanese expansion. Perhaps equally significant was a rise in American morale, with the end of an assumption (on both sides) of Japanese invincibility.

Neither Shokaku nor Zuikaku was therefore available for the next Japanese enterprise. This was an attack on the American base on Midway Island, and again American intelligence work revealed the enemy plans, which were extremely complex and included decoy attacks on the Aleutian Islands. In all Yamamoto deployed four fleet carriers (with 260 aircraft embarked), three light fleet carriers and two seaplane carriers, with no fewer than nine battleships in support, including the newest and biggest, the 18-inch Yamato. Against this armada Admiral Frank Fletcher’s TF17 had the carrier Yorktown with seventy-five aircraft, and Rear Admiral Raymond Spruance’s TF16 had Enterprise and Hornet with 168 aircraft between them, and a total of eight cruisers forming the main escort. The odds were therefore more even than Yamamoto had expected; his intelligence had discounted Yorktown because of damage received in the Coral Sea and he was unaware of the arrival in the Pacific of Hornet. Again, the aircrews on both sides did all the fighting, with the result being an overwhelming American victory. They sank all four Japanese fleet carriers, Kaga, Akagi, Hiryu and Soryu, with all of their aircraft flown by the victors of Pearl Harbor. This was somewhat offset by the loss of 109 US naval aircraft, though many of the crews were rescued. No significant part was played by the Japanese battleships, though Haruna suffered slight damage. The balance of power in the Pacific had suddenly changed.

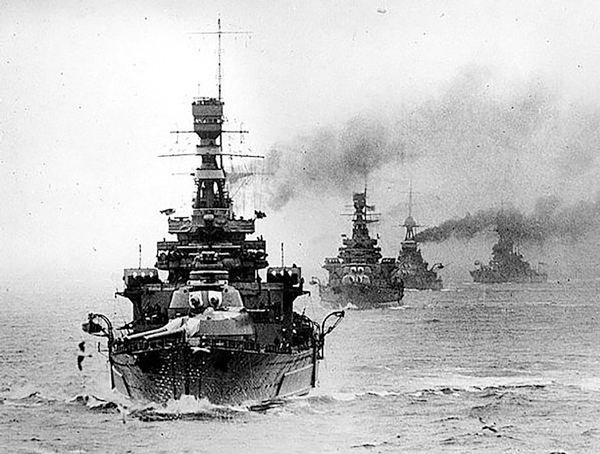

The Americans now began to redeploy their battleship strength, as well as introducing new carriers. By mid-1942 the refitted Colorado, together with Tennessee and Maryland, their damage received at Pearl Harbor repaired, were again ready for action and they were joined by the new ships North Carolina and Washington. By May 1943 the repairs to Nevada and Pennsylvania were complete, and New Mexico, Idaho and Mississippi were assigned to the Pacific, albeit now in the secondary role of fire support and escorts.

The subsequent battle of the Philippine Sea was known to American aviators as ‘the Great Marianas Turkey Shoot’, which really says it all. Again this was a battle between the aircrews, and by this time the Japanese were at a severe disadvantage. Most of their experienced crews had been lost and they were using the same aircraft types as in 1941. The Americans by now had the Helldiver, the Avenger torpedo bomber and the F6F Hellcat, which far outclassed their Japanese opponents.

F6F Hellcat fighter.

The final confrontation in the Pacific was the battle of Leyte Gulf, fought as the Americans sought to regain the Philippine Islands. Here the largest number of warships ever deployed in a single battle faced one another. The American Third Fleet was commanded by Admiral William Halsey. Task Force 38 (Vice Admiral Marc Mitscher) comprised in all nine fleet carriers and eight light carriers, with the battleships Iowa, New Jersey, Massachusetts and South Dakota, fourteen cruisers and fifty-seven destroyers and was divided into four task groups. TF 34 was the heavy striking force under Vice Admiral Willis A. Lee, who commanded the battleships Washington and Alabama and could deploy also the four battleships of TF 38. TF 77 under Vice Admiral Thomas Kincaid comprised the battleships Mississippi, Maryland, West Virginia, Tennessee, Pennsylvania and the rebuilt California. The Japanese operation was complicated even by their standards, with four separate forces, designated Forces A & C, Carrier Force and 2nd Striking Force, and these forced actions in four different areas around the Philippines.

The first Japanese battleship loss was in the Sibuyan Sea, where the huge Musashi was overwhelmed by aircraft torpedoes and bombs and sank. Then in the Surigao Strait the Fuso was first hit by bombs and then sunk by aerial torpedoes while her sister Yamashiro was struck by two torpedoes from the American destroyer Grant, and then by gunfire from the battleships West Virginia, Tennessee and California which sank her. Off Samar the escort carriers of the Task Group 77.4 came under the fire of Yamato and her four supporting battleships. Two of the American escort carriers were sunk and others damaged both by gunfire and by kamikaze attacks, but they were eventually relieved by American air and surface units. These drove off the assailants, inflicting damage on Nagato, Ise and Hyuga.

In all, 282 ships had been involved and the Japanese losses had been catastrophic – four fleet carriers and their aircraft, three battleships, six heavy and three light cruisers and eight destroyers. The Americans had lost one light carrier, two escort carriers and three destroyers. Their way to the reconquest of the Philippines was open and their mastery of the Pacific complete.

The Japanese could still deploy four conventional battleships and the two battleship-carriers Ise and Hyuga. The two after-turrets in these vessels had been removed to allow a flying-off deck to operate twentytwo seaplanes to be launched by catapult and recovered by crane after landing alongside, but there is no evidence that these aircraft were ever embarked. Both ships were sunk by aerial torpedo in the Inland Sea in June 1945. Yamato was sunk by aerial torpedo off Okinawa, in a desperate suicide mission – she had fuel only for a one-way trip. As well as a lack of fuel, there was a lack of aircraft: the Shinano, sister ship of the Yamato, was completed as a carrier, but had no aircraft embarked when she was torpedoed and sunk by the submarine Archerfish.

Mutsu had already been destroyed by a magazine explosion in the Inland Sea in June 1943, and Nagato, survived the war only to be expended as a target vessel at Bikini Atoll in 1946. The final act was the signing of the Japanese surrender on board USS Missouri. There were those who thought that a carrier might have been a more appropriate location.