Mid 1808 — Late 1808

Finau began to grow tired of the war. It was a kind of conflict not suited to his genius; he loved rather a few hard fought engagements and a speedy conquest. The enemy showed no disposition to come forth from their strong hold and attack him; and he had found by experience, that even the guns produced no sensible effect upon their fortification, situated upon an eminence, and defended by walls of clay. I could easily have devised a method to set the enemy’s fortress on fire; but I considered Toe’umu’s cause quite as just as that of Finau’s, and although the latter was my friend and benefactor, yet he had more than half assisted in the assassination of a man of admirable character (Tupouniua) who was also my friend; besides, I did not choose to be the means of dealing out destruction upon a number of innocent women and children.

Finau heartily wished for a peace, but he did not choose that his wish should be known, lest it should be attributed to fear or any other unworthy motive; in short he wanted to bring about a peace, without being thought to wish for a peace; and the difficulty was to accomplish this. He was, however, by no means deficient in policy, and he soon thought of a method. From time to time he held secret conferences with the priests, chiefly either upon religious subjects or upon political matters, as connected with the will of the gods. He spoke of his determination to remain at Vava’u and prosecute the war till his enemies were destroyed; then on a sudden, as if his heart for the moment relented, he painted in the most striking colors the evils of war, and how sorry he was that the necessity of the case obliged him to punish his rebellious subjects with so dire an evil. He then represented, in the most lively colors, the blessings of peace, and on this side of the prospect touched his hearers so with the beauty of the description that they entreated him to endeavor to make a peace. He then pretended to be inexorable, but always threw in something in favor of the Vava’u people, so that the priests at length thought there was no question at all about the propriety and honor of making a peace, and that it was their duty to persuade him to do it. For when they were inspired they had the same sentiment, and of course they considered it to be the sentiment of the gods, and represented it to him as such; when he, pretending to submit only because it was the divine will, left the matter entirely to them to negotiate, and if they succeeded, it would afford him, he said, at least one great gratification, namely the opportunity of again renewing his friendship with his aunt Toe’umu, and paying her that respect which her superior relationship required.

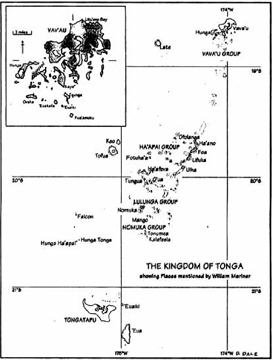

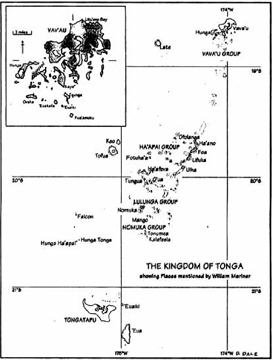

Map 3. A map of the Tonga Islands. Credit: Author’s collection.

The day after the last conference, the priests accordingly dressed themselves in mats, with wreaths of green leaves round their necks as tokens of humility, not towards the enemy, but the gods, as fulfilling a commission sacred in its nature. Thus equipped, they set out on their way to Feletoa. In the meantime, Finau gave orders that none of his men, if they met with a party of the enemy, should commit any act of hostility, but should endeavor on all occasions to avoid them by as speedy a retreat as possible, for as the gods had admonished him to endeavor to make a peace, and the priests were actually fulfilling that endeavor, any act of hostility might defeat their purpose.

The priests went four or five different times to hold conferences with the chiefs of Feletoa before they could bring about a reconciliation. For although the old men seemed willing enough to listen to terms of accommodation, influenced perhaps by their prejudice in favor of Finau as their lawful King, yet the young and spirited warriors, who saw clearly enough into the artful character of Finau, with much less of the above prejudice, constantly objected to make peace with a man on whose honor and integrity they thought it impossible to rely with any degree of certainty, and who would again give room for a quarrel with the Vava’u people whenever it suited his purpose. This was their real thought, and perhaps a just one; though they did not express their sentiments with such latitude to the priests; they merely objected their apprehensions, that in the event of a peace, Finau would, at some fit opportunity, wreak his vengeance upon them personally for having fought against him. At length, however, they said that as their lives were not a matter of so much consequence as the peace and happiness of Toe’umu and her people generally, they were willing to withdraw their objections, that the affair might be speedily settled according to the wishes of the older chiefs. The priests now returned to Neiafu with the warmest assurances from the chiefs of Feletoa, that they would pay Finau an amicable visit the following day.

The next morning the chiefs and warriors of Feletoa, with several women, were seen coming towards Neiafu, advancing two and two, all armed, painted and decorated with streamers, forming altogether a very beautiful and romantic procession, bringing with them abundance of ngatu, yams, etc. as presents to their relations. In this way they entered the fortress of Finau, and came into the King’s presence on the mala’e, where he was seated with his chiefs and matapules. The Vava’u people then laid down their spears, which were afterwards shared out to three of Finau’s principal chiefs, who again shared them out to all those below them in rank. The visitors come armed for the sake of the parade, giving up their arms afterwards as presents; those that receive them must be unarmed as a proof of their amicable disposition, and that they do not mean to get them in their power by stratagem. They seated themselves round the mala’e and kava was prepared, the young chiefs and warriors of Feletoa waiting on the company. It is an honorable office to assist at kava parties, it is therefore generally filled by young chiefs.

All this time Finau’s men were unarmed (agreeably to the custom on such occasions), but by his orders the greater part remained at their houses where their arms were deposited, for he was upon his guard lest his guests had some stratagem to play. He had merely signified to his men, that it would be better for them to remain at their houses, as it would inspire the Vava’u chiefs with more confidence than if they were present in a body.

During the time the kava was being served out, the King made a speech, addressed principally to the chiefs of Feletoa, in which he acknowledged that they were not to be blamed for their fears and apprehensions as long as they believed him to be the treacherous character which his enemies had represented him; but he hoped that these calumnies were now at an end. He was willing, he said, to excuse them for having fought in honor of the memory of their late chief Tupouniua against his murderers, for if they had not done so, he should have considered them cowards; but as most of these murderers had now by their death expiated their crime, and as he himself, as he solemnly assured them, was perfectly innocent of that affair, the present peace, he was convinced, was a most honorable one to all parties. He then made the most solemn protestations of the sincerity of his intentions towards them, and as a proof of his wish to avoid all future occasions of quarrel, he should make this his place of residence, out of the love and respect he had for them; while he should consign the government of the Ha’apai islands to Tupouto’a, to send him annual tribute.

When the kava was finished the company rose up, and the Vava’u party returned to Feletoa, to prepare an entertainment for the Ha’apai people the following day.

The microcosms of the ancient Tonga Islands provided all the elements thought to be the province of international relations on the grand scale of World Powers. Finau issued ‘general mobilization orders’ to raise his army of several divisions. His war ‘surtax’ was accomplished by having each man supply himself with a good store of provisions and by having supplies shipped out to his expeditionary forces. In the conduct of this war there were numerous power-plays among the leaders and personal rivalries were rampant. The elements of invasions, beach-head landings, and organized military combat were present. At times, unrelieved savagery occurred. ‘Peace feelers,’ and ‘peace negotiations’ were initiated when a military conquest could not be achieved. Numerous misunderstandings occurred continuously among the participants.

Finau resorted to political moves to gain a conquest when his direct military assault bogged down. After it was all over, Mariner reports in a later chapter that many thinking men wondered what it was all about, and what induced them to be so wasteful with their land, their resources, and especially their lives.

Early the next morning all the chiefs, matapules, and warriors of Neiafu painted and decorated themselves with streamers, and put on mats, in token of Finau’s inferiority as a relation to his aunt Toe’umu, chief of the fortress of Feletoa. They took spears in their hands, and, thus equipped, marched out of Neiafu two and two, with Finau at their head, carrying with them presents for their relations in the opposite garrison. In this order they entered Feletoa, and proceeded to the mala’e, where all the chiefs and matapules of Toe’umu were seated ready to receive them. A quantity of hogs, yams, and fowls, were placed in the middle of the circle, at the upper end of which a place was left vacant for the King to preside in; for, his aunt not being there, he was the greatest chief present. Had Toe’umu been present, she must have presided at the head of the circle, and the King, as her inferior relation, must have seated himself opposite to her, on the outside of the circle, among the common people; for no two relations of different rank can sit in the same circle together. On this account, and out of respect to Finau, he being sovereign, Toe’umu did not make her appearance. Finau being seated, his men, as they came in, deposited their spears in the middle of the circle, to be afterwards shared out in the same manner as was done by the Vava’u people at Neiafu the day before. They then retired to the outside of the circle, ready to wait upon the company. A large root of kava was then split into pieces, and distributed to be chewed as usual. While the kava was preparing, the provisions were shared out, ready to be eaten after the kava was drunk. This being done, and the provisions consumed, a second course of kava was prepared and served out, of which Finau having drunk a small quantity, retired to pay a visit to his aunt. When he arrived in her presence he went up to her, and, with great respect, kissed her hand, and she, in return, kissed his forehead.

When a person salutes a superior relation, he kisses the hand of the party; if a very superior relation, he kisses the foot. The superior in return kisses the forehead. There may be some doubt as to the propriety of the term to kiss in this ceremony, for it is not performed by the lips after our usual mode, but rather by the application of the upper lip and the nostrils, and has more the appearance of smelling. When two equals are about to salute, each applies his upper lip and nostrils to the forehead of the other, or they apply their lips to the lips of the other, but without any movement of them, or smack, as in our mode. Our kiss they never adopt, not even between the sexes, but, on the contrary, always ridicule it, and term it the white man’s kiss.

Finau then sat down to drink kava with her and her attendants, and, as she presided, he of course sat outside, facing her. When the kava was finished, he walked out to view the fortifications, where the matapules of Toe’umu waited on him, and pointed out everything worthy of notice. They descanted on the excellence of the plan, and then gave him anecdotes of the war, telling him where such a chief was killed, where another lost his arm or his leg, where a cannon-ball had struck, etc. As they viewed the outside of the works, they pointed out where the different murderers of Tupouniua met their fate. All this, however, they told him in answer to his queries; for it is a thing very remarkable in the character of the people of Tonga, that they never exult in any feats of bravery they may have performed, but, on the contrary, take every opportunity of praising their adversaries; and this a man will do, although his adversary may be plainly a coward, and will make an excuse for him, such as the unfavorableness of the opportunity, or great fatigue, or in state of health, or badness of his ground. In their games of wrestling they act up to the same principle, never to speak ill of their antagonist afterwards, but always to praise him. As an illustration of this character it may be remarked, that the man who called himself Fanna Fonua, a great gun, who ventured his life in his hazardous approach to me, and threw his spear at the muzzle of my carronade, never afterwards boasted of it, nor appeared to think he had done anything extraordinary, or at least worthy of after-notice. Their notions of true bravery appear to be very correct, and the light in which they viewed this act of Fanna Fonua serves for an example. They considered it in short a rash action, and unworthy a great and brave mind, that never risks any danger but with a moral certainty, or at least reasonable expectation, of doing some service to his cause. In these respects they accuse Europeans of a great deal of vanity and selfishness, and, unfortunately, with too much appearance of justice. It must be remarked, however, that these noble sentiments belong to chiefs, matapules, and professed warriors; not much to the lowest orders, many of whom will knock a dead man about the head with a club till they have notched and blooded it a good deal, and pretend it was done in the battle against a living foe; but such things are always suspected, and held in ridicule.

Finau having for a considerable time inspected the fortification, praising every where the judgment with which it was planned, retired to the house which had formerly belonged to Tupouniua, where he passed the night. The following morning he summoned a general meeting of all the inhabitants of Vava’u, which was soon accomplished, as the people were all at one or other of the two fortresses. He then gave directions to all the principal men respecting the cultivation of the country, which the late war had reduced to a sad state. He commanded that everyone should be as frugal as possible in his food, that the present scarcity might be recompensed with future abundance. He ordered his fishermen to supply him and his chiefs with plenty of fish, that the consumption of pork might be lessened. Having settled these matters, he next gave orders that the large fortress of Feletoa should be taken down, its fencing carried away by anybody who might want it, its banks leveled with the ground, and its ditches filled up; urging, as his reason, that there was no necessity for a garrisoned place in time of peace, particularly in a spot which could be so much better employed for building an additional number of more commodious dwellings. The fortress of Neiafu, he said, might remain, for it was a place not convenient to live at, and therefore it was not worth while to take any trouble about it. These were his ostensible reasons, but his real motives were easy to be seen into. He was apprehensive, that, in the event of another insurrection, his enemies might again possess themselves of this stronghold; but as to the other fortress, if he did not succeed in securing it for himself, he could easily dispossess his enemies of it, by destroying it with his carronades whenever he thought proper.

These orders were begun immediately to be put into execution, under the inspection of the chiefs of the different districts of the island. The following day the King gave orders to Tupouto’a to proceed back to the Ha’apai Islands; of which he constituted him tributary chief; the tributes to be sent to Vava’u half yearly, as usual. The tribute generally consists of yams, mats, ngatu, dried fish, live birds, etc.; and is levied upon every man’s property in proportion as he can spare. The quantity is sometimes determined by the chief of each district, though generally by the will of each individual, who will always take care to send quite as much as he can well afford, lest the superior chief should be offended with him, and deprive him of all that he has. This tribute is paid twice a year; once at the ceremony of ‘Inasi, [The word means literally: to share out] or offering the first fruits of the season to the gods, in or about the beginning of October [Tonga being in the southern hemisphere, October is spring time.]; and again, at some other time of the year, when the tributary chief may think proper, and is generally done when some article is in great plenty. The tribute levied at the time of the ‘Inasi is general and absolute; that which is paid on the other occasion comes more in form of a present, but is so established by old custom, that, if it were omitted, it would amount to little less than an act of rebellion. It may here with propriety be observed, that the practice of making presents to superior chiefs is very general and frequent. The higher class of chiefs generally make a present to the King, of hogs or yams, about once a fortnight. These chiefs, about the same time, receive presents from those below them, and these last from others, and so on, down to the common people. The principle on which all this is grounded is of course fear, but it is termed respect.

At the same time, all the natives of Ha’apai, who had come to the war, were to return with their chief. On this occasion the young Prince (Finau’s son, Moengangongo) went with Tupouto’a to the Ha’apai Islands, as he wished to look over his lands on the island of Foa. I accompanied the Prince, as I preferred his character and habits to those of his father. We arrived safe at this island after a quick passage of about nine hours.

Foa lies about 70 nautical miles south of Vava’u. Mariner and the Prince averaged nearly 8 knots for the trip. There canoe sailed more swiftly than the average modern small sailing yacht.

Shortly after the Prince, Tupouto’a and I arrived at the island of Foa, there came a canoe from Vava’u with the Tongatapu chief Filimoe’atu, [Literally, an enemy of the bonito.] who, it will be recollected, was a relation of Finau, and had joined his cause at Pangaimotu, leaving the island of Tongatapu for that purpose, by leave of his superior, the chief of Hihifo. Filimoe’atu was now on his return to the island of Tongatapu, with a commission from Finau to treat with the chief of Hihifo respecting a particular bird of the species called kalae (trained for sport). [The kalae bird has long legs and a red beak. See illustration.] Filmoe’atu, although belonging to the island of Tongatapu, was never professedly Finau’s enemy, otherwise than as Finau had been associated with the late Tupouniua whom the chief of Hihifo mortally hated. But as Tupouniua was now dead, and consequently all cause of enmity removed, Finau was in hopes he should be able to prevail upon the chief of Hihifo to make him a present of one of the first and best trained birds, of the kind in question, that ever was known, and which this chief had trained up with great care, and had long had in his possession. It was the envy of every chief that had seen it. This particular bird Finau was ardently desirous of, to practice the sport called fana kalae, [to shoot kalae birds] of which I shall give a description.

The sportsman, armed with a bow and arrows, conceals himself within a large cage, made of a sort of wicker-work, covered over with green leaves, but not so much but what he may see his game. On the top of this cage is the cock bird tied by the leg, who makes a noise, and flaps his wings, as if calling other birds to come and fight him. Within is a smaller cage, in which there is the hen bird, who also makes a peculiar noise, as if in answer to the one on the outside; but be this as it may, both cock birds and hens are attracted towards the spot, and are shot by the sportsman. This sport is practiced by none but the King and very great chiefs, for training and keeping these birds require exceeding great care as well as great expense. One man is appointed to each pair of birds, and he has nothing else to do but to attend to the management of them; and, if this is not done with great skill, they will not make the noise necessary to attract others. So much attention, in short, is paid to these birds, that their keepers are authorized to go and demand plantains for them, of whomsoever it may be, and howsoever scarce may be this article of food, even if there were a famine, and the people almost starving. If a keeper, even on such occasions, sees a fine bunch of plantains, he will go and taboo it, which he does by sticking a reed in the tree, and telling the proprietor that those plantains are tabooed for the use of the birds. These keepers live well, and are, in general, very insolent fellows, sometimes committing very great depredations, under frivolous pretensions of procuring food for their birds. The sufferer sometimes makes a complaint to the King, or whatever chief the keeper belongs to; and if the chief thinks the offence really outrageous, he orders the man a severe beating, which is usually done by inflicting heavy slaps with the open hand upon his bare back, or striking him about the head and face with the fist.

Filimoe’atu soon departed from Foa, on his way Hihifo, and arrived at this place without any accident. He was not however, so successful in the object of his journey as he expected to be; for the chief of Hihifo was by no means willing to part with a bird, which, he said, had cost great hazard to himself, and the loss of many lives, to preserve; for he had sustained wars with so many other chiefs, who had quarrelled with him on account of his refusing to give it them, that he felt, he said, more than ever resolved to keep it. However, as Finau had so strong a desire for an excellent and well trained bird of that kind, he would make him a present of a pair, which, although not quite so good as the one in question, yet would be found exceedingly valuable. Before parting, however, he qualified his refusal of the rare bird by saying, that if he ever did give it away, it must be after very mature deliberation, for it had already cost him a vast deal, and was certainly the best bird that had ever been trained. He was heartily glad to hear of the death of Tupouniua, and declared that no personal enmity existed on his part towards Finau; but, on the contrary, felt so great an attachment for him, that he would most willingly return with Filimoe’atu to Vava’u to pay a visit to Finau, but that his matapules would not allow him. Filimoe’atu having remained a day and a night with this chief, returned with the two birds to Finau, and gave him an account of his interview with the chief of Hihifo. Finau received the present, but was by no means well pleased with the refusal of the bird, on which he had so much set his heart. The following morning, however, he went out to try his success with these two, and which so far exceeded his expectations, that he wanted more than ever to have the excellent bird, and he immediately set about to obtain it by rich presents. He accordingly got ready seahorses’ teeth, beads, axes, a looking-glass, several iron bolts, and a grinding stone, all of which he had procured from European ships, and chiefly from the Port au Prince. Besides these things, he ordered to be got ready several bales of Vava’u ngatu, fine Samoan mats, and a large quantity of kava; the whole of which he gave in charge to Filimoe’atu to take immediately to Hihifo, and present them to the chief, except some of the kava, which he was to distribute among the lower chiefs and matapules, to engage them more readily in his interest. Finau himself accompanied Filimoe’atu as far as Ha’ano, (one of the Ha’apai Islands,) and took many of his principal chiefs along with him, with a view of lessening the consumption of food at Vava’u. On this expedition there were five canoes, all of which arrived safe at Ha’ano; and from this island Filimoe’atu proceeded in one canoe with thirty men to Hihifo, where he also arrived safe, and distributed his presents.

The chief of Hihifo, on this second urgent application from Finau, after some consideration, answered, that as he could not make any use of the bird himself, his time being so much taken up in constant warfare with his neighbours, and as it would not be consistent with the character of a chief to retain from another that which he could not use himself, he would, at once, resign the bird to Finau, notwithstanding the high value he placed on it, and the immense care and trouble it had cost him. The famous bird was accordingly consigned to the charge of Filimoe’atu, who returned with all convenient speed to tell the King the success of his journey. Finau was still at the Ha’apai Islands, when he received his long wished-for present; but he made no use of it till about three weeks afterwards, when he had returned to Vava’u.

In the meantime Makapapa, Lolohea Pipiki [Literally: lolohea, the shade of the hea tree; and, pipiki, to be asleep. Hence, to be asleep in the shade of the hea tree] and three others, all chiefs and warriors, secretly left Vava’u, and sailed for Tongatapu, to join Takai, (who formerly burnt Finau’s fortress of Nuku’alofa in so treacherous a manner) chief of the fortress of Pea [Now a small settlement in the central district of Tongatapu]. They took this time to leave, being apprehensive that the King might hereafter wreak his vengeance on them for fighting against him.

While Finau was yet at the Ha’apai Islands, I accompanied the Prince to the island of Tofua, to procure iron-wood, which is found there in great abundance. [The island of Tofua is the blown out cone of a volcano with elevations to 1600 feet. It is adjacent to the perfect cone-shaped volcano of Kao which reaches to 3380 feet, the highest point in Tonga. Both of these islands lie about 40 nautical miles west of Ha’apai] The Prince first obtained leave from Tu’i Tonga, the divine chief, for this island is his property, and therefore considered sacred; besides, it is supposed to be the residence of the sea gods, and on this account the people firmly believe that no sharks will hurt a man who is swimming near upon its coast, but, on the contrary, swim round him, and even pass so close as to touch him, without showing the least hungry disposition. I, however, never had an opportunity of witnessing the miraculous abstinence of this sort of fish.

On the island of Tofua there is a small volcano, situated near the northern extremity, from which smoke almost constantly issues, and pumice-stones are very frequently thrown out. An eruption of flame takes place, sometimes twice or thrice a week, and at other times scarcely once in two months, and generally lasts from one to two or three days. The way to the top is extremely difficult; but I resolved to ascent it. Taking one of the natives of the island for a guide. We began the ascent early in the morning, and, although our progress was much impeded by the quantity of loose pumice-stone, and often rendered very dangerous, we reached the top in about four hours. There was at this time no eruption of flame, which had ceased a few hours before, after having lasted three days; smoke there was, however, in abundance, but which did not much annoy us, as we were on the windward side; sundry explosions were also heard from within, like the noise of water being thrown upon burning pitch. The crater was about thirty feet diameter. While we were here, I took care not to let my companion approach too near, lest he might have some sinister intent. Such precaution was by no means unnecessary, as this species of treachery, when it can be performed secretly, is not unusual, particularly among great warriors, when they have some petty interest to consult. This, however, is not to be considered the natural disposition of the Tonga people, but a practice which, along with that of war, they have learned from the natives of the Fiji Islands, where a man never goes out, even with his greatest friend, without being armed, and cautiously upon his guard. I had, therefore, provided myself with a pistol, as a defense against any violent measures on the part of my companion. On their return down the mountain, I told my companion that I might have shot him dead, and nobody would have been the wiser, to which the man replied, “I see you are loto-poto, [clever] like the Fiji people,” meaning that I possessed policy and caution against treachery; and he added, “As I am unarmed, it is a proof that I had no ill design, and therefore did not suspect any in you.”

While on this island, I went to see the grave of an Englishman, John Norton, belonging to the boat of the Bounty, Captain Bligh, whose crew had mutinied. I was led to visit this spot from a motive of curiosity, excited by the account which the natives had given me of the death of this man. Lest, however, the reader may have forgotten this particular circumstance in the narrative of Captain Bligh, I shall first give the account as related by this gentleman.

Having put into this island for supplies, and, after having remained a few days, Bligh discovered that the natives had a design against him; in consequence of which he made the best of his way with his men to their boat. Bligh’s narrative then proceeds in the following words:

“When I came to the boat, and was seeing the people embark, Nageete wanted me to stay to speak to Eefow; but I found he was encouraging them to the attack, and I determined, had it then begun, to have killed him for his treacherous behaviour. I ordered the carpenter not to quit me until the other people were in the boat. Nageete, finding I would not stay, loosed himself from my hold, and went off, and we all got into the boat, except one man, who, while I was getting on board, quitted it, and ran up the beach to cast the stern-fast off, notwithstanding the master and others calling him to return, while they were hauling me out of the water.

“I was no sooner in the boat than the attack began by about two hundred men; the unfortunate poor man, who had run up the beach, was knocked down, and the stones flew like a shower of shot. Many Indians got hold of the stern rope, and were near hauling us on shore, and would certainly have done it, if I had not had a knife in my pocket, with which I cut the rope. We then hauled off to the grapnel, everyone being more or less hurt. At this time I saw five of the natives about the poor man they had killed, and two of them were beating him about the head with stones in their hands.

“We had no time to reflect, before, to my surprise, they filled their canoes with stones, and twelve men came off after us to renew the attack, which they did so effectually as nearly to disable all of us. Our grapnel was foul, but Providence here assisted us; the fluke broke, and we got to our oars and pulled to sea. They, however, could paddle round us, so that we were obliged to sustain the attack without being able to return it, except with such stones as lodged in the boat, and in this I found we were very inferior to them. We could not close, because our boat was lumbered and heavy, and that they knew very well. I therefore adopted the expedient of throwing overboard some cloths, which they lost time in picking up; and, as it was now almost dark, they gave over the attack, and returned towards the shore, leaving us to reflect on our unhappy situation.

“The poor man I lost was John Norton: this was his second voyage with me as quarter-master, and his worthy character made me lament his loss very much. He has left an aged parent, I am told, whom he supported.”

The account the natives gave was to the following purpose. Part of Captain Bligh’s crew had been on shore to procure water, and had all returned into their boat, except one man, who was making the best of his way after his companions, with an axe in his hand; some of the natives, perceiving the axe, resolved to possess themselves of it, particularly one of them, who was a carpenter; they accordingly pursued him, and this carpenter throwing a stone at him, knocked him down, and, coming up, beat him on the head with stones till he was dead. They then stripped the body, and dragged it up the country towards a mala’e, where they left it exposed two or three days, and afterwards buried it near the spot. They said very little about a general attack, merely stating, that some of the natives threw stones at Captain Bligh’s boat; and I, at that time, not having read the narrative, did not inquire into such particulars as I otherwise would have done. The most wonderful part of the story is, that the whole track of ground through which the body was dragged, had ever since been destitute of grass, as well as the spot on which it lay for two or three days. It was this circumstance, principally, that engaged me to visit the place, and there, indeed, I found the bare track of ground from the beach to near the place where they say he was buried; nor has it much the appearance of a beaten path, besides that it leads to and from places, where there are but few inhabitants. At the termination of this track there is a bare place, lying transversely, about the length and breadth of a man.

However trivial such accounts may appear in themselves, they are worth mentioning, with a view to contrast them with the accounts given by credible travellers, that they may tend to prove how far the statements of the natives may be depended on; besides which, in some instances, as in the present, they show what kind of superstitions they are subject to. As to the bare track, although it may not now have much the appearance of a beaten path, owing to the grass having grown irregularly on either side, yet there is every probability that, some years back, it was such, in a great degree, though now little trod. Those who are willing to keep up the spirit of the wonderful, have attributed it to this supernatural cause. Superstitions, in all countries, are much of the same kind; we have similar ones in our own; but, while men of cultivated minds disregard them, the vulgar in general most firmly believe them, particularly where there is some sensible object that appears to corroborate the tale.

While Finau was yet at the Ha’apai Islands, he often held conversations at his kava parties with Filimoe’atu respecting the nature of affairs at Tongatapu. Among other things, this chief related, that a ship from Botany Bay had touched there about a week before he arrived, and which had on board a Tonga chief, Palumatamo’ungea, and his wife, Fatafehi, both of whom had formerly left Tonga (before the death of Tuku’aho), and had resided some years at the Fiji Islands, from which place they afterwards went along with one Selly (as they pronounced it), or, probably, Selby, an Englishman, in a vessel belonging to Botany Bay, to reside there.

Botany Bay, on the east coast of Australia, was discovered on the 18th of April in 1770 by Captain Cook on his first voyage into the Pacific Ocean in the ship, Endeavor. He called the place “Botany Bay” because Mr. Banks (later to become Sir Joseph Banks), his gentleman scientist, discovered so many new and unusual botanical species during the course of this first contact with the Australian continent. A settlement, chiefly and English prison colony, had afterwards been established at the head of the bay.

At this latter place, Palumatamo’ungea and his wife remained about two years, and now, on their return to Tonga, finding the island in such an unsettled state, they chose rather (notwithstanding the earnest entreaties of their friends) to go back again to Botany Bay. The account they gave of the English customs at this place, and the treatment they met with, it may be worth while to mention. The first thing that he and his wife had to do, when they arrived at the governor’s house, where they went to reside, was to sweep out a large court yard, and clean down a great pair of stairs; in vain they endeavored to explain, that, in their own country they were chiefs, and, being accustomed to be waited on, were quite unused to such employments. Their expostulations were taken no notice of, and work they must. At first their life was so uncomfortable, that they wished to die; no one seemed to protect them; all the houses were shut against them; if they saw anybody eating, they were not invited to partake. Nothing was to be got without money, of which they could not comprehend the value, nor how this same money was to be obtained in any quantity; if they asked for it, nobody would give them any, unless they worked for it, and then it was so small in quantity, that they could not get one tenth part of what they wanted with it. One day, while sauntering about, the chief fixed his eyes upon a cook’s shop, and, seeing several people enter, and others, again, coming out with victuals, he made sure that they were sharing out food, according to the old Tonga fashion, and in he went, glad enough of the occasion, expecting to get some pork; after waiting some time, with anxiety to be helped to his share, the master of the shop asked him what he wanted, and, being answered in an unknown language, straightway kicked him out, taking him for a thief, that only wanted an opportunity to steal. Thus, he said, even being a chief did not prevent him being used ill, for, when he told them he was a chief, they gave him to understand, that money made a man a chief. After a time, however, he acknowledged that he got better used, in proportion as he became acquainted with the customs and language. He expressed his astonishment at the perseverance with which the white people worked from morning till night, to get money. He could not conceive how they were able to endure so much labour.

After having heard this account, Finau asked several questions, respecting the nature of money. “What was it made of? Was it like iron? Could it be fashioned like iron into various useful instruments? If not, why could not people procure what they wanted in the way of barter? But where was money to be got? If it was made, then every man ought to spend his time in making money; that when he had got plenty, he might be able afterwards to obtain whatever he wanted.”

In answer to the last observation, I replied that the material of which money was made was very scarce and difficult to be got, and that only chiefs and great men could procure readily a large quantity of it; and this either by being inheritors of plantations or houses, which they allowed others to have, for paying them so much tribute in money every year; or by their public services; or by paying small sums of money for things when they were in plenty, and afterwards letting others have them for larger sums, when they were scarce. As to the lower classes of people, they worked hard, and got paid by their employers in small quantities of money, as the reward of their labour. That the King was the only person that was allowed to make (to coin) money, and that he put his mark upon all that he made, that it might be known to be true; that no person could readily procure the material of which it was made, without paying money for it; and if contrary to the “taboo” of the King, he turned this material into money, he would scarcely have made as much, as he had given for it. I was then going on to show the convenience of money as a medium of exchange, when Filimoe’atu interrupted me, saying to Finau, “I understand how it is. Money is less cumbersome than goods, and it is very convenient for a man to exchange away his goods for money; which, at any other time, he could exchange again for the same or any other goods that he might want; whereas the goods themselves might have spoiled by keeping (particularly if provisions); but the money he supposed would not spoil; and although it was of no true value itself, yet being scarce and difficult to be got without giving something useful and really valuable for it, it was imagined to be of value; and if everybody considered it so, and would readily give their goods for it, he did not see but what it was of a sort of real value to all who possessed it, as long as their neighbours chose to take it in the same way.”

I found I could not give a better explanation, I therefore told Filimoe’atu that his notion of the nature of money was a just one. After a pause of some length, Finau replied that the explanation did not satisfy him. He still thought it a foolish thing that people should place a value on money, when they either could not or would not apply it to any useful (physical) purpose. “If,” said he, “it were made of iron, and could be converted into knives, axes, and chisels, there would be some sense in placing a value on it; but as it was, he saw none. If a man,” he added, “has more yams than he wants, let him exchange some of them away for pork or ngatu; certainly money was much handier, and more convenient, but then as it would not spoil by being kept, people would store it up, instead of sharing it out, as a chief ought to do, and thus become selfish. Whereas, if provision [food] was the principal property of a man, and it ought to be, as being both the most useful and the most necessary, he could not store it up, for it would spoil, and so he would be obliged either to exchange it away for something else useful, or share it out to his neighbours, and inferior chiefs and dependants, for nothing.” He concluded by saying, “I understand now very well what it is that makes the Papalangis [Europeans] so selfish — it is this money!”

When I informed Finau that dollars were money, he was greatly surprised, having always taken them for playing counters, and things of little value; and he was exceedingly sorry he had not secured all the dollars out of the Port au Prince, before he had ordered her to be burnt. “I had always thought,” said he, “that your ship belonged to some poor fellow, perhaps to King George’s cook.” (At these islands a cook is considered one of the lowest of mankind in point of rank.) “Captain Cook’s ship, which belonged to the King, had plenty of beads, axes, and looking glasses on board, while yours had nothing but iron-hoops, oil, skins, and twelve thousand playing counters, as I thought them. But if everyone of these was money, your ship must have belonged to a very great chief indeed.”

Finau and his chiefs having now remained at the Ha’apai Islands nearly six weeks, resolved to return to Vava’u, and the following day set sail; the Prince and I accompanied them. As soon as we arrived at Vava’u, the King gave orders that all the dogs in the island, except a few that belonged to chiefs, should be killed, because they destroyed the game, particularly the kalae; after which he promised himself great sport with his favorite bird. As the breed of dogs was scarce at these islands, there were not more than fifty or sixty killed on this occasion; but on these several of the chiefs made a hearty repast. Finau was particularly fond of dog’s flesh, but he ordered it to be called pork; because women and many men had a degree of abhorrence at this sort of diet. The parts of the dog in most esteem are the neck and hinder quarters. The animal is killed by blows on the head, and cooked in the same manner as a hog. I frequently partook of it, and found it very good; the fat is considered excellent. At the Hawai’i Islands the practice was almost universal when I was there, so that more dog’s flesh was eaten than pork, the hogs being preserved to be used as a trading commodity with European and American vessels. At the Hawai’i Islands most of the male dogs are operated upon, and afterwards fattened for the express purpose. I think their flesh is as good and tender as that of a sucking pig.

Finau having ordered all things to be got ready, went out early in the morning after his arrival, to try the excellence of his bird; and had very great sport. The day following he went out again; but the bird, from some cause of another, would not make any noise; and this put Finau into such a passion that he knocked it on the ground, and beat it with an arrow, and, after having almost killed it, gave it away to one of his chiefs, declaring how vexatious it was to have a bird that would not speak after having had so much trouble with it. He afterwards used the two birds that were first sent to him, and was tolerably well satisfied with them.

Finau, having at this time no business of importance on which to employ his attention, resolved to go to the island of Hunga, lying at a small distance to the southward of Vava’u, in order to inspect the plantations there, and to recreate himself a little with the sport of shooting birds and rats. I, as usual, formed one of the party. On this island there is a peculiar cavern, situated on the western coast, the entrance to which is at least a fathom beneath the surface of the sea at low water; and was first discovered by a young chief, while diving after a turtle. [In naming the island where he found this cave, Mariner’s memory erred a little. The island of Hunga lies adjacent to the island of Nuapapu and both are just south of Vava’u; but the cave is on Nuapapu, not Hunga.] The nature of this cavern will be better understood if we imagine a hollow rock rising sixty feet or more above the surface of the water; into the cavity of which there is no known entrance but one, and that is on the side of the rock, as low down as six feet under the water, into which it flows; and consequently the base of the cavern may be said to be the sea itself. Finau and his friends, being on this part of the island, proposed one afternoon on a sudden thought, to go into this cavern, and drink kava. I was not with them at the time this proposal was made; but happening to come down a little while after to the shore, and seeing some of the young chiefs diving into the water, one after another, and not rise again, I was a little surprised, and inquired of the last, who was just preparing to take the same step, what they were about? “Follow me,” said he, “and I will take you where you have never been before; and where Finau, and his chiefs and matapules, are now assembled.”

I, supposing it to be the famous cavern of which I had heard some account, without any further hesitation, prepared myself to follow my companion, who dived into the water, and I after him, and, guided by the light reflected from his heels, entered the opening in the rock, and rose into the cavern. I was no sooner above the surface of the water than, sure enough, I heard the voices of the King and his friends. Being directed by my guide, I climbed upon a jutting portion of rock, and sat down. All the light that came into this place was reflected from the bottom, and was sufficient, after remaining about five minutes, to show objects with some little distinctness; at least I could discover, being directed by the voice, Finau and the rest of the company, seated like himself, round the cavern. It is proper to mention that in the presence of a superior chief, it is considered very disrespectful to be undressed. Under such circumstances as the present, therefore, everyone retires a little, and as soon as he has divested himself of his usual dress, slips on an apron made of the leaves of the si tree, or of matting called kie. The same respect is shown if it is necessary to undress near a chief’s grave; because some ‘Otua or God may be present.

As it was desirable to have a stronger illumination, I dived out again, and procuring my pistol, primed it well, tied plenty of ngatu tight round it, and wrapped the whole up in a plantain leaf. I directed an attendant to bring a torch in the same way. Thus prepared, we re-entered the cavern as speedily as possible, unwrapped the ngatu, a great portion of which was perfectly dry, fired it by the flash of the powder, and lighted the torch. The place was now illuminated tolerably well, for the first time, perhaps, since its existence. It appeared (by guess) to be about 40 feet wide in the main part, but which branched off, on one side, in two narrower portions. The medium height seemed also about 40 feet. The roof was hung with stalactites in a very curious way, resembling, upon a cursory view, the gothic arches and ornaments of an old church. After having examined the place, we drank kava, and passed away the time in conversation upon different subjects. Among other things, an old matapule, after having mentioned how the cavern was discovered by a young chief in the act of diving after a turtle, related and interesting account of the use which this chief made of his accidental discovery. The circumstances are as follow:

In former times there lived a tui (governor) of Vava’u, who exercised a very tyrannical deportment towards his people; at length, when it was no longer to be borne, a certain chief meditated a plan of insurrection, and was resolved to free his countrymen from such odious slavery, or to be sacrificed himself in the attempt. Being however treacherously deceived by one of his own party, the tyrant became acquainted with his plan, and immediately had him arrested. He was condemned to be taken out to sea and drowned, and all his family and relations were ordered to be massacred, that none of his race might remain. One of his daughters, a beautiful girl, young and interesting, had been reserved to be the wife of a chief of considerable rank, and she too would have sunk, the victim of the merciless destroyer, had it not been for the generous exertions of another young chief, who a short time before had discovered the cavern of Hunga. This discovery he had kept within his breast a profound secret, reserving it as a place of retreat for himself, in case he should be unsuccessful in a plan of revolt which he also had in view. He had long been enamoured of this beautiful young maiden, but had never dared to make her acquainted with the soft emotions of his heart, knowing that she was betrothed to a chief of higher rank and greater power. But now the dreadful moment arrived when she was about to be cruelly sacrificed to the rancour of a man, to whom he was a most deadly enemy. No time was to be lost; he flew to her abode, communicated in a few short words the decree of the tyrant, declared himself her deliverer if she would trust to his honor, and, with eyes speaking the most tender affections, he waited with breathless expectation for an answer. Soon her consenting hand was clasped in his. The shades of evening favored their escape; while the wood, the covert, or the grove, afforded her concealment, till her lover had brought a small canoe to a lonely part of the beach. In this they speedily embarked, and as he paddled her across the smooth wave, he related his discovery of the cavern destined to be her asylum till an opportunity offered of conveying her to the Fiji Islands. She, who had entrusted her personal safety entirely to his care, hesitated not to consent to whatever plan he might think promotive of their ultimate escape; her heart being full of gratitude, love and confidence found an easy access. They soon arrived at the rock, he leaped into the water, and she, instructed by him, followed close after. They rose into the cavern, and rested from their fears and their fatigue, partaking of some refreshment which he had brought there for himself, little thinking, at the time, of the happiness that was in store for him. Early in the morning he returned to Vava’u to avoid suspicion. He did not fail, in the course of the day, to repair again to the place which held all that was dear to him. He brought her mats to lie on, the finest ngatu for a change of dress, the best of food for her support, sandalwood oil, coconuts, and everything he could think of to render her life as comfortable as possible. He gave her as much of his company as prudence would allow, and at the most appropriate times, lest the prying eye of curiosity should find out his retreat. He pleaded his tale of love with the most impassioned eloquence, half of which would have been sufficient to have won her warmest affections, for she owed her life to his prompt and generous exertions at the risk of his own. He was delighted when he heard the confession from her own lips, that she had long regarded him with a favorable eye, but a sense of duty had caused her to smother the growing fondness, till the late sad misfortune of her family, and the circumstances attending her escape, had revived all her latent affections, to bestow them wholly upon a man to whom they were so justly due. How happy were they in this solitary retreat! Tyrannic power now no longer reached them — shut out from the world and all its cares and perplexities — secure from all the eventful changes attending upon greatness, cruelty, and ambition — themselves were the only powers they served, and they were infinitely delighted with this simple form of government. But although this asylum was their great security in their happiest moments, they could not always enjoy each other’s company; it was equally necessary to their safety that he should be often absent from her, and frequently for a length of time, lest his conduct should be watched. The young chief therefore panted for an opportunity to convey her to happier scenes, where his ardent imagination pictured to him the means of procuring for her every enjoyment and comfort, which her amiable qualifications so well entitled her to. It was not a great while before, an opportunity offered; he devised the means of restoring her with safety to the cheerful light of day. He signified to his inferior chiefs and matapules, that it was his intention to go to the Fiji Islands, and he wished them to accompany him with their wives and female attendants, but he desired them on no account to mention to the latter the place of their destination, lest they should inadvertently betray their intention, and the governing chief prevent their departure. A large canoe was soon got ready, and every necessary preparation made for their voyage. As they were on the point of their departure, they asked him if he would not take a Tonga wife with him. He replied, “No! But I shall probably find one by the way.”

This they thought a joke, but in obedience to his orders they said no more, and, everybody being on board, they put to sea. As they approached the shores of Hunga, he directed them to steer to such a point, and having approached close to a rock, according to his orders, he got up, and desired them to wait there while he went into the sea to fetch his wife; and without staying to be asked any questions, he sprang into the water from that side of the canoe farthest from the rock, swam under the canoe, and proceeded forward into the sanctuary which had so well concealed his greatest and dearest treasure. Everybody on board was greatly surprised at his strange conduct, and began to think him insane. After a little lapse of time, not seeing him come up, they were greatly alarmed for his safety, imagining a shark must have seized him. While they were all in the greatest concern, debating what was best to be done, whether they ought to dive down after him, or wait according to his orders, for that perhaps he had only swam round and was come up in some niche of the rock, intending to surprise them, their wonder was increased beyond all powers of expression, when they saw him rise to the surface of the water, and come into the canoe with a beautiful female. At first they mistook her for a goddess, and their astonishment was not lessened when they recognized her countenance, and found her to be a person, whom they had no doubt was killed in the general massacre of her family; and this they thought must be her apparition. But how agreeably was their wonder softened down into the most interesting feelings, when the young chief related to them the discovery of the cavern and the whole circumstance of her escape. All the young men on board could not refrain envying him his happiness in the the possession of so lovely and interesting a creature. They arrived safe at one of the Fiji Islands, and resided with a certain chief for two years. At the end of which time, hearing of the death of the tyrant of Vava’u, the young chief returned with his wife to the last mentioned island, and lived long in peace and happiness.

Lord Byron used Mariner’s account of this love story as the substance for some lines in his poem, The Island or Christian and His Comrades.

How a young chief, a thousand moons ago,

Diving for turtle in the depths below,

Had risen, in tracking fast his ocean prey,

Into the cave which round and o’er them lay;

How in some disparate feud of after-time

He shelter’d there a daughter of the clime,

A foe beloved, and offspring of a foe,

Saved by his tribe but for a captive’s woe;

How when the storm of war was still’d, he led

His island clan to where the waters spread

Their deep-green shadow o’er the rocky door,

Then dived — it seem’d as if to rise no more;

His wondering mates, amazed within their bark,

Or deem’d him mad, or prey to the blue shark;

Row’d round in sorrow the sea-girded rock,

Then paused upon their paddles from the shock;

When, fresh and springing from the deep, they saw

A goddess rise — so deem’d they in their awe;

And their companion, glorious by her side,

Proud and exulting in his mermaid bride:

Such, as to matter of fact, is the substance of the account given by the old matapule. There was one thing however which he stated, rather in opposition to probability, namely that the chief’s daughter remained in the cavern two or three months, before her lover found an opportunity of taking her to the Fiji Islands. If this be true, there must have been some other concealed opening in the cavern to have afforded a fresh supply of air. With a view to ascertain this, I swam with the torch in my hand up both the avenues before spoken of, but without discovering any opening. I also climbed every accessible place, with as little success. If the story be true, and, however romantic it may be considered, it is still very possible, in all likelihood the duration of her stay in the cavern was not much more than one fourth of the time mentioned; and if we take the cube of 40, which is about the number of feet the place extended either in height, length, or breadth, we shall have about a sufficient number of cubic feet of air to serve for the subsistence of one individual about a month, allowing a cubic foot of air for every minute’s natural respiration; and if the frequent visits of the young chief be taken into account, there was air enough to last them about a fortnight or three weeks. But setting calculations aside, there is one ascertained fact, namely that the air was very pure at the time I was there, and none of the company made any complaint, relating to this matter, after breathing the air for the space of two hours. After all, there may be other openings which are not accessible, and which do not admit the light, not being sufficiently straight and regular; and though these openings may be but small, they may still be sufficient to renew the whole air of the cavern in no great space of time, seeing that the rise and fall of the tide in the lower part of it would act as bellows without a valve, producing the same effect, by expiration and inspiration, as the action of the diaphragm of animals. If, on the contrary, there be no other opening, then the rise and fall of the tide in the cavern ought not to be so great as out of it, because the pressure of the internal air would impede its rise, and in the same proportion it would have less extent to fall. It did not occur to me to ascertain whether this was the fact. I believe that this place is very seldom visited by the natives.

Finau and his party having finished their kava, dived out of the cavern, and resumed their proper dress; after which they proceeded across the country, and got into the public roads, to amuse themselves with the sport of shooting rats. These animals are not so large as in our parts of the world, but rather between the size of a mouse and a rat, and much of the same colour. They live chiefly upon such vegetable substances, as sugar-cane, breadfruit, etc. They constitute an article of food with the lower orders of people, but who are not allowed to make a sport of shooting them, this privilege being reserved for chiefs, matapules, and mu’as. The plan and regulations of the game of fana kuma (rat shooting) are as follows.

A party of chiefs having resolved to go rat-shooting, some of their attendants are ordered to procure and roast some coconut, which being done, and the chiefs having informed them what road they mean to take, they proceed along the appointed road, chewing the roasted nut very finely as they go, and spitting, or rather blowing, a little of it at a time out of their mouths with considerable force, but so as not to scatter the particles far from each other; for if they were widely distributed, the rat would not be tempted to stop and pick them up, and if the pieces were too large, he would run away with one piece instead of stopping to eat his fill. The bait is thus distributed, at moderate distances, on each side of the road, and the men proceed till they arrive at the place appointed for them to stop at. If in their way they come to any crossroads, they stick a reed in the ground in the middle of such crossroads, as a taboo or mark of prohibition for anyone to come down that way, and disturb the rats while the chiefs are shooting. This no one will do; for even if a considerable chief be passing that way, on seeing the taboo he will stop at a distance, and sit down on the ground, out of respect or politeness to his fellow chiefs, and wait patiently till the shooting party has gone by. A petty chief, or one of the lower orders, would not dare to infringe upon this taboo at the risk of his life. The distributors of the bait being arrived at the place appointed for them to stop at, sit down to prepare kava, having previously given the orders of their chiefs to the owners of the neighboring plantations to send a supply of refreshments, such as pork, yams, fowls, and ripe plantains.

The company of chiefs having divided themselves into two parties, set out about ten minutes after the puhi, [to blow forcibly from the mouth] (or company that distributes the bait) and follow one another closely in a row along the middle of the road, armed with bows and arrows. It must be noticed, however, that the two parties are mixed; the greatest chief, in general, proceeding first, behind him one of the opposite party, then one of the same party with the first, and behind him again one of the other party, and so on alternately. The rules of the game are these: no one may shoot a rat that is in advance of him, except he who happens to be first in the row (for their situations change, as will directly be seen); but anyone may shoot a rat that is either abreast of him or behind him. As soon as a man has shot, whether he hits the rat or not, he changes his situation with the man behind him; so that it may happen that the last man, if he has not shot so often as the others, may come to be first, and vice versa; the first come to be last. For the same reason, two or three, or more, of the same party, may come to be immediately behind one another. Whichever party kills ten rats first, wins the game. If there be plenty of rats, they generally play three or four games. As soon as they arrive at any crossroads they pull up the reeds placed as a taboo, that passengers coming afterwards may not be interrupted in their progress. When they have arrived at the place where the puhi are waiting, they sit down and partake of what is prepared for them. Afterwards, if they are disposed to pursue their diversion, they send the puhi on to prepare another portion of the road. The length of road prepared at a time is generally about a quarter of a mile. If, during the game, anyone of either party sees a fair shot at a bird, he may take aim at it; if he kills it, it counts the same as a rat, but whether he hits it or not, if he ventures a shot, he changes place with the one behind him. Every now and then they stop and make a peculiar noise with the lips, like the squeaking of a rat, which frequently brings them out of the bushes, and they sit upright on their haunches, as if in the attitude of listening. If a rat is alarmed by their approach, and is running away, one or more cry out “tu’u!” (stop!) with a sudden percussion of the tongue, and is used, we may suppose, on account of the sharp and sudden tone with which it may be pronounced. This has generally the effect of making the rat stop, when he sits up, and appears too much frightened to attempt his escape. When he is in the act of running away, the squeaking noise with the lips, instead of stopping him, would cause him to run faster. They frequently also use another sound, similar to what we use when we wish to answer in the affirmative without opening the lips, consisting in a sort of humming noise, sounding through the nostrils, but rather more short and sudden. The arrows used on these occasions are nearly six feet long, (the war-arrows being about three feet,) made of reed, headed with ironwood. They are not feathered, and their great length is requisite, that they may go straight enough to hit a small object; besides which, it is advantageous in taking an aim through a thick bush. Each individual in the party has only two arrows, for, as soon as he has discharged one from his bow, it is immediately brought to him by one of the attendants who follow the party. The bows also are rather longer than those used in war, being about six feet, the war-bows being about four feet and a half; nor are they so strong, lest the difficulty of bending them should occasion a slight trembling of the hand, which would render the aim less certain.

Finau and his friends having finished their shooting excursion, and taken some refreshment, directed their walk at random across the island, and arrived near a rock, noted by the natives as being (in their estimation) the immediate cause of the origin of all the Tonga Islands.

It happened once (before these islands were in existence) that one of their gods (Tangaloa) went out a fishing with a line and hook. [Tangaloa is the great God of the sky. His name appears is a variety of Polynesian myths throughout the widely scattered islands of the Pacific Ocean. In other islands the name of this heroic God becomes Tangaroa or Ta’aroa.] It chanced, however, that the hook got fixed in a rock at the bottom of the sea, and, in consequence of the God pulling in his line, he drew up all the Tonga Islands, which, they say, would have formed one great land; but the line accidentally breaking, the act was incomplete, and matters were left as they now are. They show a hole in the rock, about two feet diameter, which quite perforates it, and is which Tangaloa’s hook got fixed. It is moreover said that Tu’i Tonga (the divine chief) had, till within a few years, this very hook in his possession, which had been handed down to him by his forefathers; but, unfortunately, his house catching fire, the basket in which the hook was kept got burnt with its contents. I once asked Tu’i Tonga what sort of a hook it was, and was told that it was made of tortoise shell, strengthened by a piece of the bone of a whale. In size and shape it was just like a large albacore hook, measuring six or seven inches long, from the curve to the part where the line was attached, and an inch and a half between the barb and the stem. I objected that such a hook must have been too weak for the purpose. “Oh no,” said Tu’i Tonga, “You must recollect that is was a God’s hook, and could not break.”

“How came then the line to break?” I asked. “Was it not also the property of a God?”

“I do not know how that was,” replied Tu’i Tonga; “but such is the account they give, and I know nothing further about it.”

A few days after this excursion, Finau having portioned out several of the smaller islands to the government of certain of his chiefs and matapules, returned with his party to Vava’u. As soon as he arrived at Feletoa, he issued orders for a general assembly of the people, to be present on an appointed day, at a general fono, or harangue, to be addressed to them in regard to the affairs of agriculture, and to remind them of their duty towards their chiefs, and how they ought to behave at all public ceremonies; in short, upon such subjects as were more or less connected with agriculture, or with moral and political duty. These fonos are frequently held, and often upon subjects of a minor importance, such, for instance, as the expediency of repairing Finau’s canoe. On such an occasion, the owner of a certain plantation would be appointed to provide the carpenters with provisions, another to provide them with canoe-timber, a third with a peculiar kind of wood for wedges, a fourth with plait, etc. — the same with more extensive matters, as constructing a large house, planting of yams or bananas, supplying provisions for feasts, burials, etc. so that in all these matters a tax is laid upon the people, every principal owner of land providing his share. The fono now about to be held was of a general nature, to be addressed to all the people, or at least to the petty chiefs. The petty chiefs themselves often address fonos to their own dependants, when they want anything done. It must be observed, that in all these fonos, whether general or partial, the labour and care fall entirely upon the lower order of the people; for although in the general fono the petty chiefs take the care ostensibly to themselves, yet afterwards, by a minor fono, each confers it on his dependants. Notwithstanding all this, the lower classes have time enough on their hands, and means enough in their possession, to live comfortably; that is to say, they have food sufficient for themselves and their children, however large their families, and enough clothing; and withal need never be in want of a house, for that is easily built. In short, real poverty is not known among them. A fono, although it may regard some affair of a public nature, is not always upon a subject where a tax is necessary to be levied, but frequently upon some matter connected with civil policy; as for instance: when a piece of ground is laid waste by war, certain persons are appointed to cultivate it; and the chiefs are ordered not to oppress them with taxes, or with visits on their plantations, before they can supply means. It not infrequently happens that young chiefs molest women whom they meet on the road; then their husbands, if they are married women, make complaints to the older chiefs and matapules, and Finau, in consequence, orders a fono to be addressed to the people, in which the impropriety of the conduct of the young chiefs is pointed out. The offenders receive a suitable admonition, and are ordered to desist from such ill behaviour for the future. From one cause or another, there is usually a fono, either general or partial, every fourteen or twenty days. It will be easily understood that addresses of this kind are absolutely and frequently necessary, for the preservation of tolerable decency and good order, among a people who have no knowledge of any means of graphic communication. The speech is generally made by some old and principal matapule, as it was on this occasion, when the ceremony was held at Makave, about two miles and a half from Feletoa. The matapules hold a rank in society next below chiefs; they are the ministers, as it were, and counsellors of chiefs. It is their duty also to attend to public ceremonies, and to keep an eye upon the morals and general conduct of the people. As usual, a large bowl of kava was provided. The chiefs and warriors of Vava’u took a very active part in the preparation of the kava, to demonstrate to Finau their attention and loyalty. After the first bowl was drunk, while all were in expectation that Finau would give out some more kava root to be prepared, on a sudden he pronounced aloud the word “puke” (hold or arrest). Instantly all the chiefs and warriors that had been particularly active against him in the late war were seized by men previously appointed. Their hands were tied fast behind them; and they were taken down to the beach, where, with the club, several were immediately dispatched; and the remainder were reserved till the afternoon, for what is considered a more signal punishment, namely to be taken out to sea, and sunk in old leaky canoes. This transaction seemed to show how little was to be trusted to the honor of Finau, and how well founded were the suspicions of those Vava’u chiefs, who had said that no reliance was to be placed in him; and that there was little doubt but that he would take an early opportunity of exercising his revenge. They therefore acted a wise part, who, as soon as the peace was concluded, fled at the earliest opportunity, some to the island of Tongatapu, others to the Fiji Islands. It must, however, be acknowledged that Finau had received information of a conspiracy which these chiefs were designing against him; and if this be true, his conduct was certainly less reproachable. Finau being apprehensive that this attempt might fail, or that the Vava’u people, in consequence, might again rise up against him, had previously sent a canoe to the Ha’apai Islands, with orders to Tupouto’a that he and his chiefs should hold themselves in readiness to repair to his assistance at a moment’s notice. There proved, however, to be no necessity for their intervention, the conspiracy succeeding in a degree equal to his expectation. Some difficulty, however, was found in securing Kakahu a very great and brave warrior and matapule, amazingly courageous and strong, although he was highly diseased with scrofula.

Scrofula is an old term for tuberculosis of the skin and lymphatic glands. Although tuberculosis became a scourge in Tonga, and became one of the common causes of death in the islands, it is probable that the population was first infected with the disease in the course of their contact with Europeans. It is to be remembered, for example, that Captain Cooks’s second in command, Captain Clerke, who had contracted the disease while in a debtor’s prison in London died of tuberculosis in the course of Cook’s third voyage — the same voyage during which he spent so much time in Tonga, nearly three months. There was little, if any, natural resistance in the Tongan population to the spread of this germ. Therefore, more than likely, Captain Clerke and perhaps others in the crew, infected some of their Tongan friends with this disease.

The chief, Kakahu, probably had a disease related to syphilis called yaws. This disease was endemic in the South Pacific. Yaws can produce extensive ulcerations, but does not often kill its victims. Mariner reported that although Kakahu was “highly diseased” he was nevertheless “amazingly strong”—a condition unlikely if he had had tuberculosis.

Like most great warriors, Kakahu was always (according to the Fiji practice) upon his guard against treachery. They had therefore recourse to stratagem on this occasion. My services were required as the means, for I was present at the consultation of Finau and his chiefs upon the subject, and I consented, being informed that the King’s intentions were merely to confine him as a prisoner till some part of his conduct were examined into; and had it not been for the part which I was appointed to act in the business, two or three no doubt would have been killed, and several wounded, in the attempt. It must be mentioned that Kakahu, owing to his diseased appearance, was not present at the kava party after the fono (Indeed, he was seldom present on any public occasion, except to fight.). It was resolved, therefore, that a young warrior, in company with myself and others, should go and present him with kava at his residence, as soon as the above chiefs were seized. I was to sit next to him, and was to ask him for his spear, as if to look at it from curiosity; for this spear was a remarkable good one, headed with the bones of the tail of the fai (sting-ray), and which he always carried about with him. I could take this liberty better than anyone else, as I was more or less acquainted with him; and being a foreigner, my curiosity would appear more plausible, and less subject to suspicion. Having got it into my hands, I was to throw it away, and this was to be the signal for the seizure. Before Kakahu had time to hear of what was going forward at Makave, the appointed party arrived at his house, and presented him kava. I took a seat next to him; and, after a while, asked him for his spear, that I might examine the head of it; which having got into my possession, I watched an opportunity, and threw it suddenly away. In a moment Kakahu’s enemies were upon him; but he sprang from the ground like an enraged lion, and burst away from them repeatedly, with such prodigious strength, that it was with the greatest difficulty they could bind and secure him. They then took their prisoner down to the sea-coast, and put him on board a canoe, to be drowned with the rest in the afternoon.

I was not, in many instances, a voluntary supporter of Finau’s conduct. As necessity has no law, in some cases I was obliged to conform, where I could willingly have been excused, upon the principle, that of two evils, the least is to be chosen. To an honest mind it is always an ungrateful task to use any species of deception. I was in the service of the King who thought it proper to secure certain persons, among whom was one who could not easily have been taken without my assistance; that is to say, without bloodshed and a loss of lives. The King was on all occasions my friend and protector; I felt it therefore my duty to conform to his views, where there appeared nothing intrinsically bad. Had I known what would have been the fate of — let the consequences be what they might — I would not have submitted; and, in that case, by losing Finau’s friendship, and incurring his displeasure, I would not, in all probability, have lived for you to have heard of me.