Pabst Blue Ribbon (PBR) was dead.

It was 2001, and the iconic American brew was on track to sell fewer than a million barrels of beer in the United States for the year, capping 23 straight years of declining sales.1 To put that in perspective, PBR had regularly sold more than 20 million barrels a year to U.S. consumers in the 1970s.2 But by 2001, the brand had sunk so low that there was little to no hope of resuscitation.

It was around then that my team and I got the call to help bring it back. But there was a catch: there would be no advertising and no traditional marketing of any kind. And our marketing budget would be only slightly more than zero. To be honest, my firm got the job largely because we were young, brash, and cheap. I couldn’t have been more proud.

How did PBR achieve this lowly state? Partially by design. In 1985, Paul Kalmanovitz, a brewing and real estate magnate, assumed control of Pabst Brewing Company, which included brands like Lone Star and Olympia. Some believe that Kalmanovitz intentionally neglected the PBR brand so that its somewhat tarnished, blue-collar image would fade from public view, at which point he could build it back up again from scratch. For years, PBR received virtually no advertising or promotional support.

The first part of Kalmanovitz’s plan worked beautifully. Unfortunately, he died before he had a chance to initiate phase 2. And he made an even bigger mistake: Kalmanovitz left the brand to a charitable trust, violating a U.S. law that prohibits charities from owning for-profit companies. Ultimately, the IRS gave the trust until 2010 to sell the business.3

Neal Stewart, PBR’s brand manager, came to me for help. Together, we scoured the company’s sales data, looking for any sign of hope, some spark we could fan into a flame. Soon, we noticed something intriguing. There were five places in America that PBR was selling, all with seemingly very different demographics. In these cities, sales were not only healthy (relatively speaking) but growing. Neal and I scratched our heads trying to figure out what it was about those cities. We hopped on a plane and checked out as many as our meager funds would allow, thereby expending most of our marketing budget.

As we talked with PBR drinkers, a picture began to emerge. Many of these new customers had just turned 21, meaning they had been born in the late 1970s. A lot of these young people had hardcore yuppies for parents.

Today, the term yuppie refers to any moderately ambitious young person with a good job, a nice apartment, and no visible tattoos. But when they first emerged in the late 1970s and early 1980s, yuppies were a kind of political movement of people who strongly rejected the 1960s counterculture. They were anti-hippies who embraced structure, money, and status symbols like Polo shirts and “Beamers.”

In order to rebel against their yuppie parents, these young people had decided to buy their clothes from the Salvation Army, work as bike messengers or tattoo artists, grow ridiculous sideburns, and drink the least pretentious, most unglamorous beers they could find.

These were the early hipsters. Like yuppie, the meaning of hipster has now been watered down to mean anyone with skinny jeans and a pack of American Spirit. But back then, hipsters were building a new ethos for their generation, one that rejected traditional notions of status and prestige. The more a thing was considered “cool” by the mainstream, the less these young people wanted to do with it. The worst transgression for a hipster was to do something just because he wanted to be seen doing it, whether it was drinking a particular brand of beer or driving a particular kind of car. The key word was authentic. So they swarmed to things that the mainstream culture deemed hopelessly unhip.

At the time, nothing was less hip than PBR. Nothing was cheaper either. And the newly perceived target market was highly price sensitive.

The fact that PBR had no money for traditional advertising was a blessing in disguise. Throwing a bunch of TV commercials on the air, particularly ones that tried to capitalize on the brand’s newfound hipster cred, would have been a disaster. The fact that these young people had never seen a PBR ad was a huge selling point for them. It reminded them of a time when men drank beer because they liked to, not because they had been promised a backyard full of bikini models. Traditional advertising, particularly of the kind produced by big beer companies in those days, would have killed whatever tiny momentum the brand had built. In fact, any indication that the brand was trying too hard to be liked would have backfired big time.

Not that I was a fan of traditional advertising anyway. Even as a relatively young person in 2001, I had seen the writing on the wall. Broadcast wasn’t working the way it used to, and the big success stories of the day, brands such as Google and TiVo, were thriving due to word of mouth, not TV commercials. The trick was to get the most influential people among this already influential group of early hipsters to talk to their friends about PBR. All we had to do was give them good stories to share.

First, Neal and I figured out what made the brand talkable (a word you’ll be seeing a lot in this book). By talking to the young people in Portland and Pittsburgh, we discovered that they loved PBR for being unpretentious and low profile. So we hit the streets and started offering our support to creative people doing cool, interesting things just for the sake of it. If we found young people having bike messenger races, we’d hang out with them and offer them a sign to hang at their next event. We brought beer and hats to gallery openings, skating parties, juggling contests—you name it. We gave six packs of beer to Mini Kiss, a Kiss tribute band whose members were all little people.

And we never just handed out stuff and walked away. We talked to these young people about the stuff they were into. And of course, we talked about the beer.

There were no scantily clad girls passing out glow-in-the-dark coasters in sports bars, and there were no brand executives in suits making sure the events didn’t violate their corporate guidelines. If we gave someone a sign, he wasn’t required to hang it a certain way or to guarantee a certain number of attendees.

The message was simple: PBR thinks you’re awesome, and we want to help you keep being awesome.

For someone who isn’t looking to be recognized, recognition–particularly from a beloved brand–can be a powerful thing. Even more powerful is when that brand asks for nothing in return. We made an impression with these young people, and we started a lot of conversations.

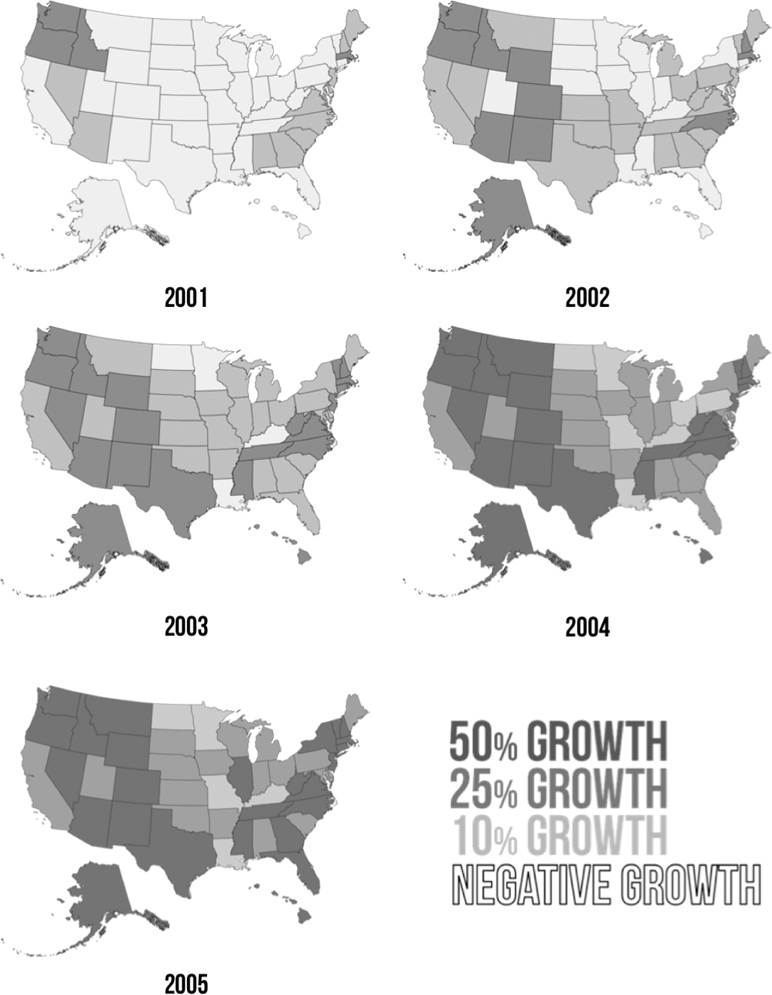

Slowly but surely, the brand began to grow (Figure 1.1). As the new hipster “tribe” spread out across the country, they brought a love of PBR with them. It required a lot of legwork from Neal, the brand, me, and a lot of others, but PBR gradually became the cool beer to drink if you didn’t care about being cool.

Figure 1.1 Pabst Blue Ribbon Sales Growth, 2001 to 2005

In 2002, PBR grew 5 percent. In 2003 and 2004, it grew 15 percent. In 2004, Pabst Brewing Company was featured in a New York Times Magazine story with the headline “The Marketing of No Marketing,” and it was named one of Fast Company’s Most Innovative Companies.4

By 2006, PBR had recorded a combined annual growth of 55 percent, and it had almost doubled its volume. Whereas in 2001 PBR was showing no growth in all but 14 U.S. states, by 2006 it had grown a minimum of 10 percent in every state, and 50 percent in more than 30 states.5 From 2008 to 2012, it was one of the top-growing beer brands in the United States.

The program worked because we gave influential people a great story to share: the story of an honest, unpretentious beer brand that genuinely supports individualism and creativity. Today, PBR is as closely associated with hipsters as Arcade Fire and ironic facial hair. So much so that, at this point, the company can sit back and reap the rewards of the consumer-to-consumer brand advocacy that results from word of mouth marketing.

All vital brands have a story to tell. Every story will be relevant and interesting to some group of people out there. And among every group of people are the influencers: the 10 percent who are compelled by their nature to tell friends about this cool new thing they found.

People are talking, and brands are a big part of the conversation. You just have to give them something to talk about.

Writers have to write, singers have to sing, and influencers have to share stories with their friends.

It really is that simple. Influencers–a group that we now know makes up about 10 percent of the population across all ages–are compelled to talk about their passions to friends, family members, and even strangers who share their interests. It is a psychological necessity for them. Just as Michael Stipe would probably go mad without producing some kind of art, or Stephen King would wither and die without his typewriter, influencers would feel pain if they couldn’t share their stories with people.

What happens to a person in childhood to generate this personality trait? Who knows? Frankly, who cares? The point is, these people exist, and you cannot stop them from sharing stories.

What you can do is get them to spread stories about your brand or product. You just have to hand the right story to the right people at the right time. Or as I like to say, if you want to catch fish, you have to use the proper bait. The trick is coming up with the best bait possible and throwing it to the fish you want to catch.

This is how word of mouth marketing works. And it does work, far better than any other form of marketing does these days. You just have to learn how to fish. This book will teach you how to do that.

Influencers are the key to word of mouth marketing. They are the ones who will carry the story about your brand or product from person to person.

If you are in marketing, you have known about influencers for a long time now. Still, it’s remarkable how little most of us really know about them. If you’re going to conduct word of mouth marketing, you need to understand what makes influencers do their thing, and how it affects other people.

Though influencers have always existed, it has only been in the last 25 years that marketers have needed to concern themselves with them. Prior to that, mainstream media did a great job helping the cereal makers and gas stations and movie studios of the world sell stuff. For every dollar they spent on TV ads, they knew they could expect more than a dollar in return. So everyone bought as much commercial time as they could. A full-page ad in the local paper got your small business a lot of attention and started conversations. Influence was something you could buy by the inch or by the second.

In the mid-1990s, as technologies and tastes began to evolve, those returns started to diminish. Some marketers saw the writing on the wall; others tried to wait it out. Today, many of the channels that used to work have become utterly ineffective. Others don’t even exist anymore. How many towns in America even have a daily newspaper these days? The old ways of doing business are gone, and marketers are searching for another way.

In a deeply fragmented culture such as ours, where people have tuned out advertising and tuned in to their own deeply individualized communities, no single channel is as consistent, effective, or reliable as those maintained by real influencers.

How do we know that influencers are real? Our first hint came in 1940, when sociologist Paul Felix Lazarsfeld conducted his now-legendary “People’s Choice” study. During the 1940 presidential election season, Lazarsfeld and his colleagues repeatedly interviewed thousands of voters to track how they decided which candidate to support. Their study divided voters into two groups: “opinion leaders” and “opinion followers.” The latter group made its decisions based largely on information passed on to them by the former, much smaller group.

Since then, decades of market research have shown that this dynamic holds true in all realms of life, not just politics. Decisions about what to buy, what trends to follow, even where to live, all hinge largely on the power of the few most influential people among us.

In his 1984 book, Influence: the Psychology of Persuasion, Robert Cialdini identified the six key principles of influence: reciprocity, commitment and consistency, social proof, authority, liking, and scarcity. His book is required reading for anyone who needs to understand the dynamics of influence.

In his 2003 book, The Influentials, word of mouth marketing pioneer Ed Keller told us who the influencers were and how many of them were out there. Through extensive research, he had found that 1 in 10 Americans was making most of the buying decisions for the other 9. That 10 percent was responsible for everything from the shift toward energy-efficient cars in the 1970s to the mass adoption of cell phones in the 2000s, he wrote. And as the culture became ever more fragmented, he said, that 10 percent only became more powerful.

Now, I’m going to tell you how to find influencers and make them work for you.

Influencers are not necessarily the most affluent people, nor the best educated. They are not, as people often assume, the vaunted “early adopters” so worshipped in our tech-obsessed culture.

Influencers are the people most deeply involved in their community, however that community is defined. It can be a school district, a college fraternity, a sub-Reddit devoted to chemistry, or a group of Portland hipsters. They are the ones constantly sharing their thoughts on the latest trend, article, or product that they know interests you too. They are the ones who told you about the latest restaurant you tried or who warned you about that awful movie you nearly saw. They are the ones who always seem to know about the trends before you do.

Having studied, thought about, and worked with them over the course of my career, I have observed that all influencers share three personality traits. Let’s take a look at each one.

In the movie City Slickers, the Daniel Stern character says he talked to his dad about baseball as a teenager because they couldn’t talk about anything else. It’s the only way they were able to express their love for each other.

For influencers, sharing stories is an expression of love. It is how they build and deepen relationships with people. They can’t just walk around all day saying, “I would like to have a closer relationship with you.” Instead, they share stories to build ties with the people around them.

Because they have this compulsion, influencers have arranged their lives to collect information about the things they’re passionate about. After all, they need to feed the beast. They know what they are interested in, and they are sure to find out about it first. They always want to bring you new information.

Lots of us like to try new things. But not all of us want to try new things simply because they are new. This is what makes influencers special. They don’t need incentives or persuasion. For them, newness is a selling point all its own.

Think about it: influencers need stories to share with people, and what’s easier to talk about than, “I tried this new thing you will love”? Stories about new things provide fresh content for influencers, so they are always in search of them.

A middle-aged golf enthusiast will drive three towns over to be the first to try the buzzed-about new putter. A twentysomething influencer will go out on a rainy Monday night to hear a new band before her friends do. A 10-year-old influencer will subscribe to the Lego catalog so that he can tell his friends about the new play sets before they hit stores.

An influencer knows if he has information first, you will not only listen to what he says but you will also come back to him for another conversation once you have something to say about it. Yay, more conversation! He also knows that if he has tried something many more times than you have, you will come to regard him as an expert, and you will seek his counsel when you have questions on the topic.

New information is fuel for influencers, so they are drawn to things that they haven’t heard of before. You don’t have to worry about incentivizing influencers to sample that new toothpaste or listen to that new recording. The incentive is already there. Just say the word “new.”

True influencers are compelled by something deep inside them to share stories about brands and products. It’s just the way they are.

Trying to motivate them through discounts or rebates won’t work. In fact, most influencers will be driven away by such things because they will feel that you’re trying to buy their loyalty rather than earn it. Worse, your financial incentive might pollute the relationships they are trying to build by telling stories about your brand.

Let me explain with an example from my own work.

A few years ago, my agency was helping out a private school called Academe of the Oaks in our hometown of Atlanta, Georgia. This school overwhelmingly relied on word of mouth from its students’ parents to bring in new applicants. To drive that word of mouth, the school offered a $500 tuition rebate to any parent who referred a new family. Basically, the school was betting that at least some of its students’ parents were community influencers.

To keep track of the referrals, the school asked new families to write the name of the person who referred them at the bottom of the application.

Big mistake.

In three years of running this program, only a few parents claimed their tuition discount. Why? Because the program was a turnoff to parents who actually had influencer personalities. The last thing they wanted was their friends’ thinking that they were recommending the school just to get $500 off their own tuition. The program was killing word of mouth because it provided exactly the wrong kind of motivation for influencers.

By convincing them to drop the $500 bounty and to use a few other word of mouth tactics–which we’ll discuss in Chapter 3–we moved the school from budget crisis to expansion mode. Now it has kids on waiting lists.

Influencers share stories because they want to build bonds with people. For them, that is the reward, and it comes from a place deep within them. If they think what you’re selling will be interesting to people they know, that is all the motivation they need. You cannot buy their interest–or their approval–with discounts or rewards.

For dyed-in-the-wool marketers, people who have spent their entire careers trying to entice consumers with offers, this can be a tough mindset to grasp. I get that. We have been trained to dangle 10 percent off, two-for-one, limited-time-only promos. But those things won’t work well with the influencers. So working with them means thinking differently.

The influencer ecosystem is very much a democracy. Power is granted by the people. The only reason influencers have any power at all is that 90 percent of the population willingly follows their lead. That 10 percent sets the trends, and the rest of us go along with them. Most of the time, we don’t even realize it. But we are happy to do it.

This is true across every category and every age group. Middle-aged men are following influencers when they buy a BMW as much as seven-year-old girls are when they buy Silly Bandz (or, more accurately, pester their parents to). Regardless, the 10 percent rule holds: 10 percent of the population decides what to buy, the other 90 percent goes along for the ride.

Though influencers have probably always existed in some sense, they have never held more power than they do now. There are a couple of reasons for this.

Everyday people have lost faith in mass media and, particularly, in marketing messages. According to a 2010 study by social scientist and marketing researcher Daniel Yankelovich, 75 percent of Americans do not believe that companies tell the truth in their advertising, and that’s across all channels. So we bailed. We have been so inundated with jingles and promises and guarantees for so long that we have simply tuned them out (and thanks to technologies like DVRs and ad blockers, we can). From the mid-1990s to the mid-2000s, we gradually gave up on the idea that companies are going to help us make good decisions. These days, I expect my friends to help me do that, and so do most other people.

That is not an opinion. It is a fact–and a well-established one at that. According to a 2010 report by McKinsey & Company, up to 50 percent of all purchasing decisions are based primarily on a friend’s recommendation. And according to research firm Nielsen, 92 percent of consumers trust recommendations from people they know, and–this is the most amazing part–70 percent trust online recommendations from strangers.6

Yes, they would rather trust a stranger on the Internet than your TV commercial.

In the music business, it is largely accepted that the days of blockbuster album sales–Michael Jackson’s Thriller, U2’s Joshua Tree, records that sell tens of millions of copies–are long behind us. This is because there is no single pop culture anymore. Today, we are all tuned in to our own subcultures, our own personalized media mixes. And each of these subcultures has its own influencer class. All the emo kids listen to a handful of emo influencers, all the marathon runners listen to the running influencers, and so on. Mass media simply isn’t set up to address that kind of specialization.

Once in a while, an artist breaks into what remains of the mainstream to become a crossover hit, like Lady Gaga or Katy Perry. But even their albums rarely sell more than 2 or 3 million copies. Thriller, by comparison, has sold somewhere between 60 and 100 million.7

Influencers, on the other hand, thrive on it. Nothing thrills an influencer like having a group of people coming to her for advice and recommendations on a mutual obsession. In this way, a segmented culture reinforces its own divisions. For example, once I know that people look to me for guidance on, say, classic horror movies, I am going to double my efforts at becoming an expert in the field.

That is an enormous amount of buying power in the hands of a few people. These days, a word from a friend or an established expert in his category is far more powerful than any TV commercial starring a celebrity, no matter how much that celebrity may be getting paid.

The power of word of mouth marketing is that it is a targeted message from a trusted source, every single time.

Another reason we look to influencers more now is that we are simply too busy. Time and money are scarce. As an average American who is fully consumed with my job, my family, and all my other commitments, I do not have time to research what tequila I should be buying or what gym I should join. Frankly, these things aren’t that important to me. Instead, I let my influencer friends—to whom these things are important–figure that out for me. Then, the one time every year that I need it, I call them and ask for their recommendation.

So why do companies still spend time trying to reach 100 percent of the population with their advertising messages?

Excellent question. In my experience, most marketers already know that there is a lot of waste when using this channel. They know that the vast majority of people who see their commercials will not be moved to do or buy anything, much less convince anyone else to. But as the classic John Wanamaker quote (which, because this is a marketing book, I am legally obligated to include) goes, most marketers know that half their advertising budget is being wasted, they just don’t know which half. So they keep spending all of it in the hopes that some of it will make an impact.

The truth is, if you are spending most of your budget on media that promises reach and frequency (I’m looking at you, broadcast television), you are probably wasting far more than half of your advertising budget. Actually, 90 percent is more like it.

As those channels have broken down, influencer networks have strengthened. Luckily for us, that makes them easier than ever to find.

When I think about influencers, I think about the first time I visited Hawaii. I remember looking out at the water and thinking how beautiful it was. I couldn’t see any fish, and at least at first, I didn’t really think about them. It was enough to appreciate what I could see of the ocean from a distance.

Then I decided to go snorkeling. Once I put my mask on and my head underwater, I discovered about 50 fish swimming around me. It was a whole other world, and it was gorgeous. Had I never put my head underwater, I never would have seen they were there. The fish didn’t care either way.

Influencers are a lot like that. Most of the time, we don’t think about them, largely because we can’t see them. But they are out there, doing their thing, whether you pay attention to them or not. If you want to figure them out, you have to get your head below the surface.

There are three rules to finding and working with influencers: let them come to you, use the right bait, and fish where the fish are.

If I gave you a net and fins and a speargun, could you catch a fish? Maybe. You would have to swim very fast and take careful aim at a moving target. But you might be able to do it. Of course, that would get you only one fish, and you would have expended an awful lot of time and energy.

Or you can let them come to you.

It’s the same with influencers. There are plenty of agencies and research firms that would be thrilled to take your money to help you find the people who are most likely to be influential in your category. You can then bring those alleged influencers into your office and ask them questions about their passions and hobbies. Observe them. Are they sharing stories with you in a way that indicates they do so naturally? Do they seem to have good social skills? Do they show genuine enthusiasm about certain products or topics? You can go through all the checklists and say, “OK, this person may be an influencer.”

But there is an easier and far more effective way to attract influencers. Get some good bait and dangle it in the water. The truly passionate people will come check it out. They will come to you. The trick is figuring out what bait to use for the particular fish you want to catch.

Follow me back to Hawaii for a moment. As I was snorkeling, some guy, clearly a local, waded into the water carrying a bag of frozen peas—not your usual beach snack. Well, this guy knew what he was doing. He grabbed a handful of those peas and threw them in the water.

If I was impressed by the 50 fish I saw when I first put my head underwater, I was downright astonished at what the peas attracted: the 50 fish turned into about 300! And every kind you could imagine, just streaming out of the reef—which itself is stocked with nutrients—to check out the peas.

Just like the fish, influencers are swimming around in a sea of information, but they are always looking for new stories to consume. They love a good story, or an opportunity to share something new. You just have to offer them the right bait. That’s how you lure an influencer.

In the case of marketers, your bait is a story about your brand or product. The trick is figuring out what the right story is and presenting it in a way that is most attractive to influencers.

You have to offer something of interest. Something authentic, new, interesting, and cool. In short, something worth talking about.

Let’s start with a bad example of influencer bait. Let’s say you are a furniture company, and you make a high chair that is so wonderfully designed it’s been included on lists of the best-designed items on earth. You have a hugely devoted following, and most people with young children have at least heard of your chair. Now, here comes the seventy-fifth anniversary of your company, and you want to sing it from the mountaintops. Well, guess what? Other than your employees and another 20 fans worldwide who have named their children after your company, nobody cares. In fact, other than those people, nobody cares about any of the following: your anniversary, the fact that your company is family owned, or how proud you are that your grandfather started the company 75 years ago. Too many companies want to talk about stuff that matters greatly within their four walls but isn’t likely to inspire a single conversation outside of them. Don’t fall into the trap of thinking that just because it’s important to you, it’s interesting to anybody else.

Here’s some good influencer bait: a new study shows that children who use your high chair sit in an adult chair and feed themselves far earlier than other kids. That’s a story that will get picked up and talked about because it is relevant and interesting to parents of young children everywhere.

You need to ask yourself, what is something about my brand that can really inspire a conversation? And who are the people who will want to have this conversation?

It’s important to note that not all the fish actually ate those peas. Some just swam up, tasted them, and then went about their fishy business. Others only glanced at them and swam past. Some, of course, gobbled them up.

Even if your brand story hits all the right notes, not every influencer is going to be interested in it. That’s natural. No influencer is influential in every category. In fact, we find that most are influential in three to five categories maximum. So you need to make sure you’re offering the right bait to the right fish.

Of course, you have to get the bait in front of the fish. Which brings us to our third rule.

You wouldn’t fish for sharks in shallow water, and you wouldn’t look for NASCAR enthusiasts at a Sephora in Manhattan. You have to throw your bait into the waters frequented by your fish.

Luckily for us, people of similar interests have a tendency to congregate. Figure out where your fish are schooling, and then take your bait to them. Tell your story in a fan forum, drive your new pickup to the parking lot of a monster truck show, or show off your amazing new sweeper in front of parents lining up to see Santa (more on that later).

If you want to catch sharks, you’ve got to get in a boat and venture into deeper water. And you’ve got to have huge chunks of big, bloody bait to throw in. Fish where the fish are.

Once you’ve caught your influencers, what are you going to do with them? In many ways, word of mouth marketing is like fishing in a catch-and-release river. You’re not going to stuff these influencers and mount them on the wall. You want them to take your bait and go back to where they congregate with like-minded people so they can spread it around. You need to have a system in place so that they can keep coming back for more.

Just as fish will continually return to a spot that contains food, influencers will come back to you if you are constantly supplying interesting, shareable information. Keep feeding them stories, and they will keep coming back.

The most important thing to remember is this: don’t chase them. Influencers have a deep desire to identify themselves to you. Your job is to give them as many opportunities as possible to do so and then to feed them what they want. And keep feeding them. That’s how you spread your story as effectively as possible to as many people as possible.

As marketers, we need to focus on what the story is and where we’re going to throw that story into the water. That is the sum total of what our jobs will be if we’re trying to work through people who are influential.

A few years ago, some companies in Asia got busted for putting ground-up gypsum–a mineral commonly used as fertilizer or as a prime ingredient in plaster and drywall–into baby formula. Apparently, it helped make the product more filling. Once caught, they dropped gypsum as an ingredient and then placed stickers on their packaging announcing, “Now gypsum free!”

True? Yes. Authentic? No.

Influencers are sharers, not sellers. They do not want to be bought, and they will have a negative reaction to anyone they suspect is trying to sell them something. Try it, and you will drive them away.

Influencers can smell PR talk, and they’re not interested in it. You have got to approach them with an authentic, believable message, or you will be wasting your time and theirs.

Your story has to be true, and not just cleared-by-the-lawyers true. It has to be honest, and it has to respect your audience’s intelligence.

Here’s another way to tell when you’re being authentic: Most of the time, authenticity is scary to a company. It requires that you share a fairly unvarnished reality, and an unvarnished reality is going to have lumps. In a world where your competition is all basically the same, it may seem like being the same is the safe bet. But once you make the decision not to be that way, you begin to set yourself apart. You create some cognitive dissonance. And that not only gets a customer’s attention but it also gets her respect.

To illustrate my point, consider an exception that proves the rule about advertising. In 2009, Domino’s Pizza launched a TV campaign that featured real employees listening to real focus groups talk about how awful their pizza was. The word “cardboard” was tossed around like so much shredded mozzarella. These employees, including the CEO, promised to do better. It was how they introduced their new pizza, allegedly redesigned “from the crust up.”

That commercial had power because it deviated from the norm–namely, decades of TV commercials featuring cheesy glamour shots of what we all knew were less-than-premium products. Jaded as we are about commercial messages, most of us assumed Domino’s knew it was pulling the wool over our eyes (or at least trying) and didn’t particularly care as long as the orders kept coming in. Seeing the company’s executives get their feelings hurt by criticism of their food was enough to make customers stop and pay attention. That commercial was something to talk about. And who wasn’t just a little curious to try that new pizza?

And let’s remember: In the Internet age, when everyone is a critic, reporter, and publisher, your company is probably fooling itself if it thinks it can successfully push an inauthentic image of itself. In an age of radical transparency, transparency itself isn’t so radical. It’s just the smart, honest thing to do.

Still, some people in your company are going to say, “We can’t do that. We’ve never done it that way before.” There are going to be people who don’t want to do it. So it’s going to be hard. You’re going to have to have meetings, build a team, be politically astute. But the payoff comes when you start having conversations with consumers, and they see you are being authentic, and they stand up and pay attention. And then they tell their friends about it. The more authentic you are, the more cognitive dissonance you will create. People aren’t used to hearing, “Hey, our product could be better, and we’re trying to improve it now.”

If your story is not authentic, influencers will not share it because that story will hurt their credibility with the people they are trying to influence. This is why you have to deal with influencers in the most authentic way possible. If an influencer smells something that’s funny or thinks something is weird, she is not going to share that with her friends.

Advertising is, by its very nature, selective. The creative process for making an ad is focused on emphasizing the appealing elements of your product while leaving out the other stuff.

That is the exact opposite of how you need to approach influencers. You need to give them enough information to do their “job” properly.

Word of mouth marketing can be difficult for advertising people who are trained to stress the positive and ignore the negative or even just to highlight the feature the company wants to talk about. When it comes to influencers, you have to give them as much of the story as you can and let them choose what to talk about. In many ways, that’s what you’re using them for. They are the ultimate targeting mechanism. They can decide on the spot whom to tell what about your brand, and what not to tell them.

Not because they care about your bottom line. They don’t. They care about sharing useful information with their network.

True influencers don’t waste people’s time by telling, for example, a grandmother about the latest iPhone’s cool new social gaming features. A true influencer will tell his grandmother about the phone’s new video-chatting app that will let her see and talk to her grandkids on weekends. As a marketer, you have to give her enough information to make that decision.

I have a friend who is a huge fan of all things Disney, particularly the parks. When she goes to a soccer game, she may talk to five different people about what’s new at Disney World–and those will be five different conversations. She’ll tell the guy who’s in danger of losing his job about the new value package, but she’ll tell the woman who just made partner about the new bed sheets at the Grand Floridian.

The influencer seeks to always have the most up-to-date and accurate information because she wants to have a continued relationship with the people she’s influencing. She wants to be a resource. And she wants to be a resource because she’s superinterested and superpassionate about her thing, whether it be Disney World or wine or tropical fish.

The more aspects of your story and the more pieces of the puzzle you give to an influencer, the more able she is to put those pieces together in a way that is relevant to the person she is talking to. In that way, influencers are more efficient than a company ever could be. They will nearly always send a very targeted message directly to the appropriate person.

No one has ever written an algorithm that is more efficient, accurate, or reliable than the human brain.

Also bear in mind that these people are storytellers. What respectable storyteller would tell the story of Goldilocks without the scary part where the bears get angry about the intruder? Nobody wants to hear, or tell, half a story. So you have to tell a complete one, not just the parts you want to emphasize.

The path that information travels when spread by an influencer can be a very circuitous one. Unlike your television commercial, it is not being pushed in someone’s face during every timeout of every Sunday NFL game. The information spreads at its own organic, socially acceptable pace. This requires something else marketers–and frankly, their bosses–aren’t known for: patience.

Let’s say you and I are friends. In reality, we will probably get together, what, every two months? Maybe less? Now let’s say I know that you love barbecue sauce every bit as much as I do. Does that mean I am going to call you the moment I find out about a new flavor or recipe? Probably not. In the grand scheme of things, it’s just not that important. More likely, I will wait until I see you again, and then I will make a point of telling you about it. And you might not act on the new information until I ask you if you’ve tried it when I see you again two months later.

When left to its own devices, word of mouth travels at a leisurely pace. Sometimes, as in the case of a new movie, that pace is a fast one because time is a factor. Otherwise, it can wait. So we have to as well. With rare exceptions, you can’t share stories with an influencer today and expect to see your sales increase a month from today. Word of mouth requires patience.

Don’t think that information traveling at a slower, more natural pace will somehow make less of an impact once it finds its target. On the contrary, that organic pace gives word of mouth marketing its power because it’s so unlike in-your-face advertising. Word of mouth marketing is shared willingly and naturally. The listener’s defenses aren’t up; he is receptive to new information. In-your-face advertising makes people feel bombarded. Word of mouth makes them feel like they are part of the club.

This is one reason it’s important to plan your word of mouth campaigns far in advance, to work with influencers as early as you can. You can’t force a seed to grow into a plant more quickly. Plant the seed today and reap the harvest later. Give a Disney fanatic information about the park and trust that, when the time comes, the information will find its mark. Because even if it’s been months since I’ve seen my friend who knows everything about Disney, whom do you think I’m going to call if I do plan a trip to Orlando? That’s when your seed will bear fruit.

But first, you have to plant the seed. How do you do that with influencers? It requires a little bit of generosity on your part. It requires you to give them a taste. As we’ll discuss in the next chapter, it requires you to give them their two-ounce sample.