chapter two

Hope

Hope is the thing with feathers–

That perches in the soul–

And sings the tune without the words–

And never stops–at all–

And sweetest–in the Gale– is heard –

And sore must be the storm–

That could abash the little Bird

That kept so many warm–

I’ve heard it in the chillest land –

And on the strangest Sea–

Yet – never–in Extremity,

It asked a crumb–of me.

Emily Dickinson

Grandma Julia, My Irish Blessing

“Above all, be the heroine of your life, not the victim.”

Nora Ephron

Wellesley Class of 1996 Commencement Address

My beloved grandmother, Julia O’Toole Wessell, came to this country from Ireland in 1929 at age nineteen. She sailed alone across the Atlantic on a ship called the Adriatic, part of the famous White Star Line, which included the Titanic. As a little girl, I loved to hear Grandma tell stories of her dangerous and exciting journey. She was a natural storyteller (and honestly a bit of an exaggerator, as all good storytellers are) and she kept me spellbound with tales told in her musical Irish brogue.

Julia set off from her small village of Dun Laoghaire alone, leaving behind her parents and younger siblings, Mae and Denis. Dun Laoghaire is a beautiful little seaport town, and my grandmother loved to tell how the English troops landed there during the Easter Rebellion of 1916 and marched into Dublin. My great-grandmother, Catherine Fitzpatrick, went into labor with her youngest daughter Mae the day the troops came ashore, and Julia, just a tiny girl of six, had to run out into the streets filled with marching English soldiers to fetch the doctor.

As an adult, I understood that Grandma came to this country fleeing poverty (her father was an invalid, having been exposed to mustard gas as a soldier during World War I). But listening to her stories as a child, I would never have known that. Julia O’Toole was an incredibly proud woman— no matter her circumstances, she always viewed her experiences, past and present, in the rosiest possible light.

In her stories of her voyage on the White Star Line, she sounded more like a movie star or heiress than a poor girl traveling alone with little more than the clothes on her back and a bit of money pinned to her underwear. From her life, I have learned many things, but the one that has served me best is to put on some lipstick and laugh at circumstance whenever you can (even after a good cry).

Grandma was a bit of a snob about the fact that she had a sponsor in the United States, her Aunt Nora, who worked as a laundress in New York City and saved enough to pay her passage in third class on the Adriatic. This meant that she did not have to travel in steerage, nor did she have to suffer the indignities of Ellis Island.

“I had a sponsor, don’t you know, Kelley,” she would say to me in confiding tones, shaking a be-ringed finger so I understood the gravity and importance of such a thing. “I was not in steerage with the rest of the rabble. I was not with the likes of them. We had gay dances and parties. Oh, the dances! I was lovely, a lovely lass like you, and my feet were never at rest with all the dancing. The handsome gentlemen were lined up for me to dance with them!”

Grandma was a bit vain about her looks, and especially so in retrospect. From her descriptions, her younger self sounded a bit like a cross between Grace Kelly and Marilyn Monroe. While this is not exactly confirmed in her photos, her creative license was one of the many things I adored about her nonetheless. As I said, she put a positive spin on everything!

My favorite part of her voyage story was when she was crowned “Miss White Star Line” on the final night of her journey. My grandmother was so charming and outgoing that she had befriended all of the employees on the ship, and they wanted to make her last evening special. “At the 3rd Class Costume Ball I was dressed as Miss White Star Line,” she would tell me, eyes shining with the memory. “The chambermaids all got together and pinned monogrammed napkins all over my dress and created a gorgeous, elaborate headpiece for me. I won first prize! We were all in high spirits, as we would be docking into America the next day. Everyone was talking about sailing past the Statue of Liberty, seeing it shining ahead on the water. Oh, the excitement on the ship, Kelley! My heart was pounding as I danced. It was thrilling to be nineteen, a beautiful young girl, and beginning my adventures in the greatest country on earth.”

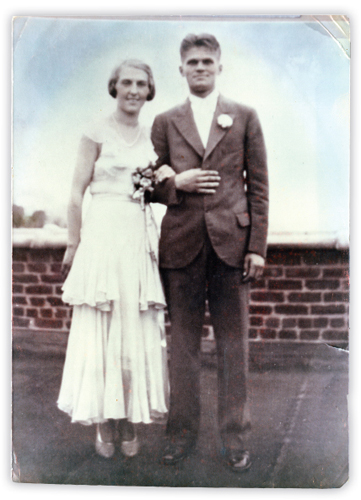

My grandparents, Julia and Harry, on their wedding day.

Listening to her stories as a teenager, I was in awe of her bravery: traveling alone at such a young age with no way to ever reach her family if she needed them. It was dangerous, romantic, the stuff of novels—and I ate it up. Grandma was always being pursued by handsome “rogues and devils.” “Of course I had to put a stop to their fresh ways, don’t you know,” she’d tell me with a wink.

She had left behind a fiancé, Boxer Byrne, a soldier who was “black Irish handsome” and mad for her. I always felt a little sorry for Boxer, who was devastated by her headstrong departure for America, leaving him heartbroken and alone. The story went that after Grandma left, all the O’Tooles would take cover when they saw Boxer approaching. He’d come up to them, red-faced and bellowing, “Where’s Julia?” I always hoped that he’d found a new fiancée after that.

Her first job was as a live-in maid at the mansion of the owners of the Saks Fifth Avenue store. According to my Aunt Julie, this is where she developed her love of fashion and home décor, which lasted all of her life. As she recalls, “She adapted well after she learned the ropes and, when looking for the dumbwaiter, knew to look for a contraption in the hall, not a speechless man!”

She was provided with a safe and comfortable room, good food, some time off, and was able to attend Mass. She missed her family terribly and sent money home to Ireland every month, something she did her entire life, even after she married and had children, when she could spare only a few dollars at a time.

Her work as a live-in maid provided her a ready-made social life that eased her homesickness, as there were lots of other young women working in the house that she befriended. Grandma loved to tell stories of how she and the other girls would flirt with the delivery boys in the markets and make dates to meet them on various New York street corners. They would go up to the top floor of the mansion and peek to see if the boys would show up!

A year or two after her arrival in the United States, Grandma contracted rheumatic fever and became very ill. She was terrified that her employers would find out that she was sick, and went to great lengths to conceal her illness from them. “I would have been deported if I could not work, don’t you know, and sent back to Ireland, which was a mark of great shame. I would have been a burden on the state,” she would tell me gravely.

For some reason her rheumatic fever stories always featured her crawling downstairs in a weakened state before the family awakened in order to secretly drink water from the flower vases because of her terrible, unquenchable thirst. I never quite understood that one but it certainly increased the drama factor in her story!

When she became very ill, her employer, a kind woman, did not fire her or have her deported but sent her to a hospital. To aid in her recovery, the woman then sent Grandma to her summer home in Deal Beach, New Jersey, to spend a month by the ocean. She rode all the way to the coast in an open roadster, driven by the son of the family. Grandma loved it, of course!

Grandma’s Visits

All during my childhood and teens, Grandma gave me wonderful, glittering things when she would visit from New York. Just the words New York conjured images of glamour and sophistication for me. She brought me her old purses and costume jewelry she no longer wore—the bigger the better, as far as I was concerned. I can probably blame her for my purse obsession. Photographs of me riding my tricycle at age three feature a large lady’s handbag circa 1945 draped over the handle-bars. Even at three I could not venture down the driveway without my bag!

Grandma’s precious castoffs always had a great story behind them. “Oh, Kelley, Mrs. Werthheimer gave this one to me the summer I was twenty-one and I carried it the night I met your grandfather at Gristedes Market and we went out for a chocolate malted together. I looked quite stylish and your grandfather was so handsome with his gorgeous Swedish hair and dimpled chin.” Everything Mrs. Werthheimer and Mrs. Roskin gave Grandma was “fine, fine” and “only the best.” Grandma’s employers were wealthy women, or as she liked to say in awed tones with a raised eyebrow, “high society.”

As a little girl I loved all the heavy purses and glittering, colorful necklaces and brooches, and I would accessorize my Sears T-shirts and shorts with multiple elegant “jewels.” When I was fifteen, Grandma gave me a small beaded evening purse, which I prize to this day. It is covered in intricate ivory glass beads and seed pearls, with a sparkling design fashioned of crystal buttons at the clasp. Inside is a beautiful cream lining of pure silk.

I was dazzled by it. I can still see Grandma’s shining face as she pressed it into my hands, voice hushed with significance. Have I mentioned that she loved to make a production of everything? “Now this, Kelley, is very special indeed, and I have been waiting for you to be old enough to have it,” she said. “It’s from a very fine store in New York and Mrs. Roskin gave it to me to carry when your grandfather and I went to The Top of the World Lodge for cocktails and dinner on our wedding anniversary. I want you to have it, and promise me you’ll carry it to wonderful parties and dances where I know you will be the belle of the ball!”

And she went on to describe her elegant employer carrying this “fine, fine” purse to the ballet and the opera, and to all the beautiful charity balls and sparkling parties she attended in New York. I was fifteen then, and for the first time my attention shifted from the wealthy society ladies and their fabulous castoffs to my grandmother herself.

My entire life I had listened to Grandma’s tales of Mrs. Wertheimer and Mrs. Roskin, whom she “worked for,” but until that moment it had never really occurred to me to ask her what she actually did. I was too dazzled by the items themselves, and the stories surrounding them, to really think about my grandmother as a person other than “Grandma.”

We were cuddled on the sofa in my parent’s knotty wood-paneled 1970s style den, and I remember asking, “Grandma, what was your job for Mrs. Roskin?” She leaned in, confiding, “Oh, Kelley, I did everything for her, handled all of her affairs. But most importantly, I was her confidante, her trusted advisor, and her most steadfast friend.”

I nodded, fascinated as always by the dramatic language and passion my grandmother brought to every conversation. It didn’t really occur to me in that moment that this was a rather unorthodox job description. I just drank it all in: my grandmother, the trusted advisor.

Later, after Grandma and Grandpa had driven back to New York in their cavernous Oldsmobile (Grandma buttoned stylishly into her “car coat” in the passenger seat), I proudly showed my mother the sparkling evening purse. I was chattering on about how exciting Grandma’s life and jobs in New York had been when I glimpsed a fleeting sadness in my mother’s eyes. “Kelley,” she said quietly, “Grandma was Mrs. Roskin’s maid.”

At the time, my teenage self was a bit let down. My glamorous grandma from New York was a maid? But now, her life and legacy is something I am fiercely proud of. The optimistic and passionate way my grandmother lived her life taught me a valuable lesson: that the situation you find yourself in, whether it’s your job or your health or your family, does not define who you are. Our essential spirit does not have to reflect our external circumstance.

I have no doubt that my grandmother, who worked for Mrs. Roskin for more than thirty years, did become her trusted advisor, her true and constant friend. My grandmother worked hard, did her job with extraordinary care and pride, and thrived in her adopted America. The spirit of my grandmother, and those like her, is the spirit that has made this country great.

Julia O’Toole Wessell took great satisfaction in the fact that she was a hard worker who helped support her family of four children through very difficult times. Yes, she loved glamour and elegance, and yes, she was a maid. She saw no disconnect in that. And thanks to her, neither do I. The value of doing a job and doing it well is enough in itself.

Anthony Trollope wrote that while it is necessary for a young person starting out in life to decide whether he will make hats or shoes, the more important decision is whether to make excellent—or mediocre—hats or shoes. My grandmother cleaned, tidied, organized, and beautified. She did her job with excellence, and she did it with inimitable style.

KC

“You must learn some of my philosophy.

Think only of the past as its remembrance gives you pleasure.”

Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice

I know some people might say my grandmother was an embellisher, someone who made her life out to be something it really wasn’t. I disagree. She had the ability to take whatever she had, no matter how small, and truly make it shine. There was something utterly compelling and undeniably American about her optimism. She never felt sorry for herself. She put on her lipstick—usually a bright Max Factor coral—fixed a nice pot of tea and had a good laugh.

She adored looking good. My grandmother was one of those women who never gave up on the idea of herself as a desirable, beautiful woman. Just coming over for dinner with our family, when she was well into her eighties, Grandma would be fully made up, hair styled, wearing a great outfit and jewelry. She was quite censorious of the sweat suit wearers of our time. She believed in making an effort.

This outlook was forged over decades of living a life that was never easy. As I grew older, my mother told me more stories of how she and her two sisters and brother worked all through school to help keep their struggling family afloat. My grandfather, Harry Wessell, a first generation American, worked construction and helped build the Holland Tunnel. His father, Thor Albert Wessell, had come through Ellis Island from Sweden in 1890.

My grandfather grew up in the gritty Hell’s Kitchen section of Manhattan, home to many poor and working class immigrants at the time. He had to quit school in the eighth grade to help put food on the table. Like my grandmother, he was a dreamer and an optimist. He tried to start several businesses but was usually unsuccessful. Despite his lack of education, he was a prolific writer of fiery letters to the editor of the local newspapers throughout his life.

My mother and all of her siblings worked various jobs after school from an early age to help support their family. My mom, a pretty, popular majorette in high school, worked in the cafeteria, cleaning trays and wiping down tables between lunch shifts to get the hot lunch for free.

I asked her once if she was ever embarrassed about cleaning the cafeteria in front of her friends and I was surprised by her response: “No!” she said. “I was really proud of myself for getting that job, which lots of other kids wanted back then. I earned the money to buy myself a hot lunch, which was great since I was sick of packing peanut butter sandwiches.” By today’s standards, they were poor, but my mother doesn’t ever remember feeling that way. She believes my grandparents’ outlook, their optimism and humor, fierce pride and work ethic, had everything to do with that, in spite of the hard times.

My mother remembers the year that my grandfather lost all of their savings in a failed construction venture and couldn’t find work. My mother, her older sister, and brother had outgrown their coats and had nothing to get them though the freezing upstate New York winter. The family had only one car and everyone had to do lots of walking, no matter the weather.

During that difficult season, my grandparents gratefully accepted coats and clothing from the Salvation Army, whose kind volunteers also showed up at their door with a Christmas dinner, complete with a small, brightly decorated bottle brush tree and wrapped toys. My Aunt Julie still remembers how delighted she was with her gift, a soft brown teddy bear.

According to my mother, accepting this charity hurt my grandparents’ pride, but there was no other choice. They survived the winter, but my grandmother never forgot how humbling it was to be the recipient of those donated coats and gifts. The following year, the day after Thanksgiving, my grandmother woke my mother and her older sister early and took them down to the Salvation Army to ring the bell and help out.

My mother told me that she only once dared to complain about having to get up early to volunteer for the Salvation Army. “My mother set me straight,” she said. “She looked me hard in the eye and said, ‘We have a debt to the Salvation Army. They gave us Christian charity when we needed them. And we will repay our debt by helping them help others. We will hold our heads high.’ ”

This was the pride of my grandmother, and the work ethic of her entire generation. You could not hold your head high without hard work. They may have received coats from the Salvation Army one year, but they would help give them out the next.

In spite of these hardships, my grandmother had a great hopefulness about her that never wavered. Many immigrants of her generation expected life to be hard and full of struggle, so they kept their dreams modest, their lives focused on saving and preparing themselves for whatever loss or difficulty lay around the corner.

But my grandmother, even into her old age, kept a joyful expectation of surprise about her. I know her strong faith in God’s goodness was a big part of that. She always had a beautiful strand of rosary beads nearby that I found fascinating and mysterious, having been raised a Baptist. Her Catholic faith was an integral part of her inherent optimism, a source of both joy and sustenance for her.

She and my grandfather did achieve their own piece of the American dream. All four of their children were successful and helped them in their own ways after my grandparents retired. My grandparents eventually left New York and settled into a small rented house near my parents’ home in Russellville, Kentucky, where Grandma was an immediate hit, charming everyone in town with her infectious laughter and irresistible tales. In the winters, they enjoyed a month at my parents’ beachfront condo in Florida, playing golf and making friends with the other retired snowbirds.

With her musical Irish brogue, stylish scarves, and love of a highball by the pool, I’ll bet those other retired ladies had no idea just how hard my grandmother’s life had been. Not that she would want them to— she would much rather brag about her successful, educated children and grandchildren, her American dream.

She always made me feel that I had made her proud, and she absolutely adored Rand. He used to joke that Grandma was good for his ophthalmology practice. Whenever she had an appointment to see him, she would sit in the waiting room and brag to anyone within earshot about what a brilliant surgeon he was. “He knows everything about the eye, don’t you know,” she would say in serious, confiding tones to whomever was seated next to her.

She was that way with all of her children and grandchildren: lavish with praise, delighted with even the smallest achievement, and a true believer in all of our best qualities and talents. I remember taking her to Wal-Mart when I was home for a visit from college, and she walked me around the store so she could introduce me to the manager and all of her favorite cashiers, just so they could see “how gorgeous my granddaughter is!” While it was occasionally embarrassing, she made each of us feel special, worthy, and loved.

In Memory

The last time that I saw my grandmother was in July of 1996. I’ll never forget that afternoon, and it has served as a reminder to me ever since—a reminder to recognize what is truly important in life, even in the busyness of the everyday, and make time for it and value it.

It was around three in the afternoon and I had just gotten our four-month-old baby Duncan down for a nap. I had sent three-year-old William off to the park with a babysitter while I hastily readied my house for cookout guests that evening. I was fairly new to both cooking and entertaining and not feeling at all confident as I rushed around picking up toy trucks, cleaning surfaces, marinating chicken, and chopping vegetables.

I was panicking a bit and starting to regret inviting so many people. I impatiently barked hello into the phone when it wouldn’t stop ringing. It was my mother. “Hey honey!” she said. “I brought Grandma over to Bowling Green and we just got out of her doctor’s appointment. She feels a little more energetic today and wants to stop by your house for a quick visit.” My first reaction, I’m ashamed to say, was annoyance. Didn’t my mom remember I was hosting a cookout for my new book club and their spouses tonight? I was way behind on my food prep and needed to sweep the deck and wipe at least half the fingerprints from the glass doors before my guests arrived. My boys had consumed all of my energy that morning and I hadn’t even had a shower yet. I most certainly did not have time to sit and chat with Mom and Grandma.

I opened my mouth to start my excuses but something in my mother’s voice stopped me cold. Grandma had been losing weight and I knew my mom was worried about her. I found myself saying, “Sure, come on over. I’m here.” In the fifteen minutes before they arrived I kicked about a hundred Legos and Thomas Trains under the couch, dramatically lowered my standards for the presentation of my home, and put my hair in a ponytail.

We sat on the deck in the light summer sunshine. I brought Grandma a glass of white wine. We talked and laughed. Listening to the rainfall of her words, I remember feeling an unusual lack of concern about the ticking clock, the impending arrival of my guests, my messy house and unprepared meal. The afternoon sun felt good as I relaxed and enjoyed the unexpected time with her and my mom. It wasn’t often that it was just the three of us anymore.

Grandma finished her wine and said she was getting tired. I told her that I was so glad that she had made the impromptu visit, and I meant it. She looked out at the backyard of my new home, with its towering oak and hickory trees and view of the lake. She smiled and said, “Everything is so lovely here, Kelley. I always knew you would have such a beautiful home. I know you are going to have much happiness here, and you deserve it, my love.” And she smiled with her shining blue eyes. It felt like a benediction. My happiness was hers. That is what it means to be a mother, a grandmother, to love someone more than yourself. It was a diaphanous moment, pure and light.

My grandmother died suddenly the next night. I am forever grateful for that final, golden afternoon with her and my mother.

Fifteen years later, I carried Grandma’s castoff purse to the White House Christmas Party. As I walked into the foyer, my eyes were wide with the beauty and grandeur of it all—the dozens of sparkling Christmas trees, the Marine Band in their gleaming red and gold brocade uniforms, the glittering people standing in those historic marble halls filled with paintings and crystal chandeliers. Standing there, I took a deep breath and looked down at my arm. That little beaded purse just shined. And I knew Grandma was smiling.