chapter three

Courage

“Don’t wish me happiness.

I don’t expect to be happy all the time.

It has gotten beyond that somehow.

Wish me courage, and strength, and

a sense of humor. I will need them all.”

Anne Morrow Lindbergh A Gift from the Sea

Salvaged Heirlooms from Faraway Places

“Bir elin nesi var, Iki elin sesi var.”

“One hand has nothing, two hands have sound.”

Turkish saying, author unknown

There is a certain power in old things that are loved and handed down, carrying their stories with them like a message in a bottle. My friend Sevgi built a business by taking very old, worn-out things, Turkish kilim rugs, and transforming them into beautiful, purposeful things—unique purses and bags, shoes, belts and other accessories.

She called her business Carpetbackers. She scoured the bazaars and second-hand shops of Turkey for her rugs, created designs for her factory there, and sold them at wholesale markets all over the United States. I have one of her purses and I love the artistry and intricacy of the kilim rug design, but also the idea that long ago in a distant country this was part of someone’s home, someone’s life, was lived on and worn out—and then recreated into something stylish and beautiful that is sporting about the US in 2015.

Sevgi and I used to marvel at the coincidence that we became friends at a small liberal arts college in Memphis, Tennessee, in 1981, after we had both lived in Turkey as children at the same time during the early seventies. She lived in Istanbul and I lived in Izmir, but we traveled to each other’s cities quite often, and I like to think that we passed each other in a bazaar or marketplace back then, smiling shyly as we picked out trinkets or sweets from a street vendor’s cart.

My father was an Air Force Sergeant and our family moved around the world for much of my childhood. My parents and brothers lived in England before I came along in September of 1963, at Homestead Air Force Base near Miami. I started kindergarten at General Arnold School in Lincoln Nebraska, but before that I had already lived in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina and Austin, Texas – a true Air Force brat.

When I was in second grade my Dad got the news that we would be transferred to Izmir, Turkey. Turkey? We were all anxious about it, having no idea what to expect from life in a Muslim country so exotic and far away, but our two years there became my family’s most memorable, wonderful adventure.

I loved everything about Turkey—the beautiful, dramatic beaches and landscape, the language, the colorful, chaotic bazaars, the friendly people and outlandish street peddlers to whom my mother would call down from our apartment balcony for chai in the afternoons. Wiry brown boys would carry it up on elaborate brass trays, the hot chai steaming in its tiny, exquisite gold-rimmed glasses.

Every week my mother would send me flying down the stairs with a few liras to buy Turkish sweets and candies from the cart vendors, yelling out in my meager Turkish, “Geliyorum!” (Hold on, I’m coming!). The peddlers always had a big smile for the small American girl with the wispy white-blonde hair and the sweet tooth.

I immediately became friends with a little Turkish girl in our building, the apartment manager’s daughter, and I would often have dinner with their family, seated on richly colored kilim rugs on the floor. Their doorway was covered with beautiful blue glass “evil eyes” to ward off bad spirits, and I was mesmerized by it. None of them spoke a word of English and I spoke no Turkish in the beginning, but that did not get in our way— we were both seven-year-old girls who loved dolls, and that was all that mattered.

My new friend was fascinated with my extensive collection of Barbies and their stylish American wardrobes and accessories. She and I would play for hours, sending Barbie, PJ, and Skipper out on all kinds of perfectly accessorized adventures speaking “half-half” Turkish-English. I can still see my Malibu Barbie, coolly insouciant as she lounged on exotic kilim rug beaches in her bikini and tiny sunglasses.

I certainly didn’t expect to meet my next Turkish friend in 1981 in Memphis, Tennessee, but I’m so very grateful that I did. Sevgi is one of the bravest, most unconventional people I have ever met. She never takes the expected path, but instead forges ahead with something no one else has thought of. She was a Phi Beta Kappa business major, but instead of taking an entry-level job somewhere in Atlanta with the rest of us after college, she signed with a modeling agency and flew off to Japan to work. (Yes, she’s tall and beautiful too.)

A few years later she started her business, managing production from her factory in Turkey and traveling across the US to merchandise her products. Fluent in four languages, Sevgi has lived all over the world and recently returned full time to the United States after living in Gibraltar for eight years.

When I think of Sevgi, I am reminded of these words from Helen Keller: Life is either a daring adventure or nothing at all. Sevgi’s story is about two women, Bedia and Sumer, her grandmother and mother, both of whom personify a true sense of daring, adventure, and love of life.

“I was no longer scared.

I could see what was inside me.”

Amy Tan

The Joy Luck Club

Turkish Rebels

Sevgi’s Story

My mother Sumer was just one year old when it happened, too young to comprehend the incident that caused her mother to develop a hard, impenetrable shell, withholding the love and warmth that she so desperately needed. As my grandmother Bedia was changing her diaper one morning, Kaya, her firstborn son, who had been playing by her side just seconds before, was suddenly nowhere in sight. In terror, Bedia stared at the wind-ruffled curtains of the open fifth-floor window.

The day before, Kaya had been mesmerized by an acrobat walking on a tightrope. Maneuvering his tiny body through the window guards, Kaya was seen by neighbors trying to balance himself on the ledge, holding out his arms, shouting, “Look at me! Look at me!” Down the steps ran my desperate grandmother. Grabbing her son, she ran all the way to the hospital ten blocks away, clutching his lifeless body.

Sumer’s childhood was infused with the feeling that her mother was withdrawn from her, unlike the way she treated her older sister and brothers. “She doesn’t like me,” Sumer told her older sister when she was five years old. In horror, she listened to her sister explain what had happened four years earlier. From that day on, feeling forlorn and responsible, she recoiled from her distant mother, the wall between the two growing taller.

Sumer grew up in an old neighborhood in Istanbul, with cobblestone streets and slanted wooden buildings. Bedia, who was fiercely feminist, shunned wearing a veil and refused to set foot in a mosque, where women and men had to pray separately. She was tough, having worked in a factory at the age of ten while her father was at war and her mother pregnant.

When my grandfather, Arif, was stricken with severe diabetes and had to quit his job, Bedia took control and started working from home sewing scarves for Vakko Department Store. All day she toiled in front of the sewing machine, a filterless Birinci cigarette hanging from her mouth. In the evenings, she liked to play solitaire as Arif read Pardayanlar, a swashbuckler series, to the children and their friends. The diabetes did little to thwart his humor—my mother remembers his laughter permeating the house.

Forced to grow up at a tender age, Sumer’s shyness and insecurity gave way to a strong and independent spirit. She adored school. “Raise your hand if you have a piano at home and would like to take piano lessons at lunchtime,” asked the teacher one day. Sumer’s hand was the first to go up.

“Your daughter is a very talented piano player,” the teacher told her mother at a school meeting months later. Bedia was taken aback. “But we have no piano at home,” she answered. That evening, with her head held low, Sumer led her mother to the windowsill where she had hand-drawn a keyboard, hidden safely behind the curtains. A few days later, Sumer came home to find two men hauling a piano up the staircase. Sumer and her sister had to eventually quit school to stay at home sewing scarves to help make ends meet. When old enough, they both began work as “coffee girls” at the Istanbul Hilton Hotel, wearing ornate Turkish costumes, and befriending travelers from all over the world. One such group was the Copp family of Memphis, Tennessee, who asked her if she would like to be sponsored and return to the United States with them.

“No,” her parents told her, “absolutely not!” Persistent and determined, Sumer sought the help of an influential friend, a well-known Turkish poet, and was able to access the necessary paperwork for her move to the United States, only to defiantly inform her parents the night before her departure.

In Memphis, living in the posh yet warm home of the Copp family in Morningside Park, Sumer attended White Station High School. With just six years of education behind her, she tested at the senior level after one year at White Station.

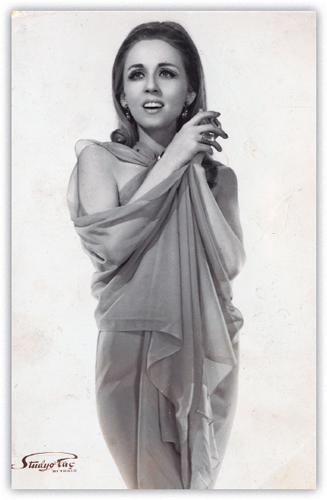

A newspaper article about her in the Memphis Commercial Appeal prompted The Lausanne School for Girls to offer her a full scholarship for her senior year. While studying at Lausanne, Sumer became a scholarship student at Memphis College of Music. After graduation, she was awarded a full scholarship to study voice at what is now Rhodes College, where I would attend decades later.

Through friends there, she met and fell in love with my father. With her dreams set on studying opera at Juilliard, she discovered she was pregnant with my sister. Marriage and three more children quickly followed. The “Turkish Girl” at first felt unaccepted by my father’s traditional southern family, but she soon captured their hearts with her warmth and beauty.

They settled in Memphis and my father began working alongside his dad in the appliance parts business started by my entrepreneurial grandfather. It was Memphis in the early sixties: a hotbed of racial tension and social change. Just like her mother Bedia, who had rebelled against the second-class treatment of women in religion, Sumer’s sense of justice and defiant spirit led her straight into the Civil Rights Movement.

In her Volkswagen Kombi, Sumer drove black voters to and from the voting booths. She opened a bank account at Tri-State Bank, which had mostly black customers, where she made many friends. Supporters and friends of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., such as Dr. Billy Kyles, frequented our home, where my mother and father hosted social gatherings and meetings.

When Dr. King arrived in Memphis for a televised church service, Sumer was the only white person sitting in the choir pews. During the service, when all stood up, hand in hand, singing “We Shall Overcome,” Dr King, who had been sitting in front of my mother, turned around and noticed her. The cameras zoomed in as he leaned over to embrace her, and they finished the song with their hands clasped.

When my parents returned home that night, they found my irate great-grandfather, who was unaccepting of their involvement in the Civil Rights Movement, waiting for them at the front door. I can only imagine the shouting match that ensued, but my parents were unyielding. Together they forged their own social circles in Memphis, raising their young family with values of social justice and respect.

In 1967, eleven years after leaving Turkey, Sumer returned home for a visit. Old friends, who had heard of her American training in voice and piano, encouraged her to perform at a local festival. The crowd was mesmerized by her operatic vibrato as she sang popular American songs like “Summertime” and Elvis Presley’s “In the Ghetto.” The audiences grew larger and more enthusiastic as she performed several more times during her visit.

Sumer’s dreams of singing and performing were reignited, and with four children in tow, my parents moved from Memphis to Istanbul. My father found work as a contractor providing goods for the PX stores, where military personnel in Turkey shopped for US products. He loved his new life in Turkey, where he charmed everyone he met with his friendly manner and captivating blue eyes. My mother was quickly on her way to becoming a famous pop singer, performing in concerts across the country and releasing the first of several albums. Then, in May of 1970, our world came crashing down when my father was killed in a car accident. He was 35.

My mother was devastated. With four children to support, she went into survival mode and continued her singing career. Performing regularly at a club nearby, she managed to keep us all going on her own. There was nothing she couldn’t do. I remember how she rolled up her sleeves at home, even fixing the heating unit in our house herself, her slender arms covered in black soot.

For extra income, our beautifully renovated two-story home in Tarabya, a suburb of Istanbul, was turned into a makeshift movie set for Turkish films. Tall light fixtures were constantly carried up and down the stairs, the floors and furniture meticulously wiped and polished for each scene. With the income from the movie business and her singing, my mother was able to provide us with a beautiful home with a large garden filled with fruit trees and a swing set that still sits there today.

We regularly spent time with my grandmother Bedia and grandfather Arif, and also my mother’s siblings. I remember my grandfather Arif making us laugh with his stories as we four grandchildren stood in line to massage his achy shoulders in exchange for fruit candies and liras. I remember my grandmother Bedia as a tough woman with a work-hardened face who would suddenly surprise me with a fierce bear hug.

My mother says she will never forget the look of shock and pride in Bedia’s eyes the first time she saw her sing onstage. She was overcome with joy that Sumer had accomplished something that she herself was never allowed. It was only then that Sumer learned that Bedia had also once dreamed of being a singer, had even sung on one of the very first records ever produced in Turkey in 1936, but her disapproving family considered it scandalous and stopped the release of the record.

Sumer still struggled with the wall that existed between her and her mother, but sensed that Bedia was proud of all she had accomplished in the years since her defiant act of running away to the United States in high school. In 1972, Bedia was diagnosed with liver cancer. Ironically, my mother was the only sibling at her side in her last moments.

As she held her mother in the hospital bed, Bedia’s protective shield broke away and she tearfully apologized for holding back the love she felt she could not relinquish for all those years. When her soul left her body, Bedia’s hardened, lined features finally softened and became a face at peace, the look of a woman reunited with her three-year-old son.

Suffering this second loss, my mother courageously carried on. She gave us a childhood of music and laughter, despite her own pain. She threw her energy into her career, recording several more albums. She became a famous pop star, and we four children even performed on one of her albums, singing the Turkish version of “Sing a Song” by The Carpenters.

Television appearances followed, and soon the paparazzi began to intrude on our lives. Alone, my mother felt unable to protect us from a stalker who eventually set fire to the utility room adjacent to our house. After that, the demands of her celebrity and career on the heels of so much loss became overwhelming and she decided to move us back to Memphis in January of 1975, where our American grandparents welcomed us home with open arms.

I was twelve years old. Although we had spent several summers in the United States with my grandparents, moving back was a culture shock. Television and toys replaced climbing trees, playing soccer, jumping into the Bosphorus with our dogs, picking fruit, and growing vegetable gardens. School was now “too easy,” and it took some time before friendships formed. At first we did not fit in and had to survive the persistent teasing refrain, “Turkey…Gobble! Gobble!”

Our return coincided with the start of busing, which my mother celebrated despite the heated resistance of many during that time. Some transferred to private schools, but Sumer was determined that we remain in the public system. Her dream of seeing her children receive a top-quality music education was fulfilled, as we all excelled in our school band program.

With her outgoing personality, my mother became a confidant of many of our friends, and our home the neighborhood hangout. Not only was she doing the job of double-parenting four kids, she was becoming, as we grew older, our best friend.

As we all left home to attend college and tackle life, my mother found an opportunity to return to Turkey in 1987 and has been living there ever since. Sadly, the country has taken a terrible turn in recent years, with increasingly less religious and social tolerance. My mother described it to me eloquently in a letter:

“It is a recurring nightmare from which one cannot break free. The sun is shining with total absence of light—garlands of ignorance, greed, wickedness, deception, chicanery, cruelty; vultures in turbans and brides in black veils—spiraling undercurrent gobbling up all that is good—art, music, ballet, theater, poetry, philosophy, and basic freedom. Women are sent back to the Middle Ages and little boys are being brainwashed. Bleak? Oh, yes. Worst of all? No one in the world cares.”

It is a sad irony that my passionate and adventurous mother, who has bravely stood up for justice throughout her life and taken great risks to fulfill her dreams, is now watching her beloved homeland become less free and tolerant than it was more than forty years ago. In her seventies now, she remains defiant. She stands, a testament to all that can be accomplished by a woman of fortitude and daring, unafraid to venture beyond the safe and comfortable confines created by others. Her name is Sumer. She stands.