Chapter 9

There’s Snoring, and Then There’s Snoring: Dealing with Sleep Apnea

In This Chapter

Understanding the causes of snoring

Understanding the causes of snoring

Looking into treatment options

Looking into treatment options

Identifying dangerous snoring: Sleep apnea

Identifying dangerous snoring: Sleep apnea

How many cartoons have you seen in your lifetime that dealt with snoring? You may laugh when you see the woman holding the pillow over her husband’s face in that comic strip, or when you watch a snoring gag on tele-vision or at the movies. But to a snorer’s long-suffering significant other, snoring is no laughing matter.

Snoring isn’t too much fun for the person sawing those logs, either. When sleep apnea accompanies snoring, the snorer may be chronically sleep-deprived, and his or her brain may be starved for oxygen. This situation can lead to a whole host of medical problems.

Before you decide that snoring is just another one of those little practical jokes on the human race (along with bald heads and thunder thighs), read this chapter. We tell you everything you may want to know about snoring.

We even review all those gadgets and sprays you see on late-night television (when you should be sleeping) that promise to stop snoring. We tell you which ones work and when you can save your money. Your significant other will thank you for checking out this chapter.

Snoring 101

When you’re young, you probably fell asleep and slept through the night without producing any noticeable sound — other than the occasional grunt when your dog stole the covers. But the snorer produces an entire symphony of sounds as air passes through his or her nose and throat. Well, perhaps symphony isn’t exactly the right word. Cacophony is more like it.

Just in case you think snoring isn’t all that big a deal, consider that a New York man was evicted from his apartment for loud snoring. After hearing a tape of the man snoring, the court upheld the landlord’s right to evict, believing the woman’s claim that the snorer was disturbing everyone in the building. The snorer visited a sleep specialist who diagnosed sleep apnea and started treatments to reduce the poor man’s snoring and improve his sleep-related breathing disorder.

Some people are too embarrassed to admit they snore.

Some people are too embarrassed to admit they snore.

Other people may be unaware that they snore (but their bedmates sure know, which is why so many snorers sleep in a room by themselves).

Other people may be unaware that they snore (but their bedmates sure know, which is why so many snorers sleep in a room by themselves).

So what causes snoring? Read on!

Looking at the science of snoring

Several things can cause ordinary snoring. When a person’s airway is narrow, or when it’s partially blocked from a cold or nasal congestion, the increased suction can cause the soft tissues in the upper airway to collapse inward and touch each other. This collapse further blocks the airflow through the nasal passages to the lungs and forces sleepers to breathe through their mouths. As air flows through this narrowed passage, the soft tissues vibrate rapidly, much like the thin membrane that produces sound in a kazoo. And voila — the sound we refer to as snoring is created. Decreased muscle tone, fatty deposits in the throat, and secretions or swelling and inflammation from colds or allergies can also contribute to the problem.

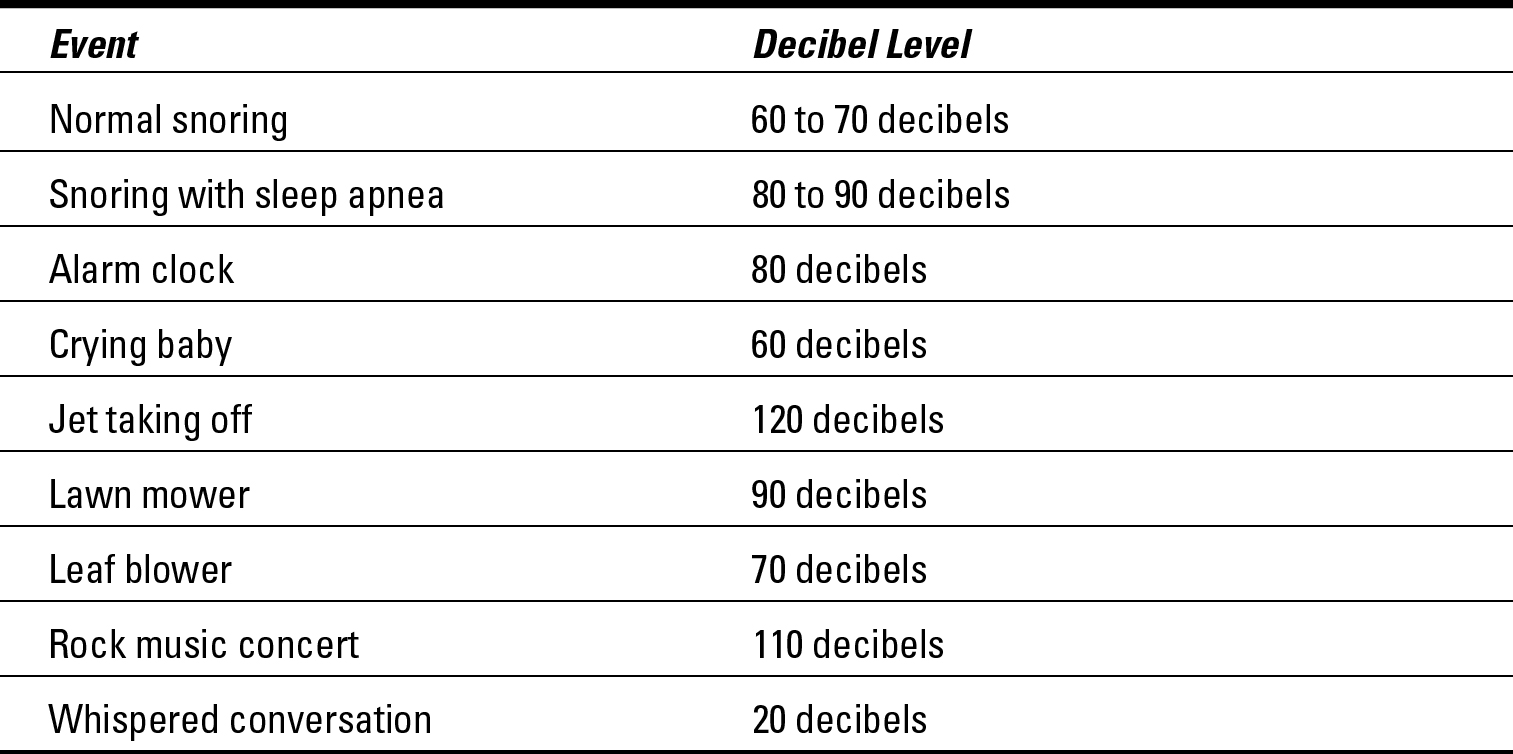

All about decibels — can you hear me now?

Decibels aren’t a measure of loudness (a common misconception), but rather a measure of acoustical force. A decibel is one tenth of a Bel, named after Alexander Graham Bell, the father of the telephone. The decimal scale is logarithmic, increasing 10 fold for every 10 decibels measured. The smallest measurement, 1 decibel, represents the softest sound the human ear can hear — equivalent to a feather falling to the ground.

Human conversation ranges from about 25 to 90 decibels, depending upon whether you’re whispering in your boyfriend’s ear or shouting at your kids. At 70 decibels, the average telephone conversation is louder than the typical 50-decibel face-to-face conversation.

The average snore ranges from 60 to 70 decibels, or about as loud as a vacuum cleaner. Snoring associated with sleep apnea averages 80 to 90 decibels, equivalent to a chain saw or a lawn mower. Earplugs may provide the snorer’s bedmate some relief; non-prescription earplugs block as much as 25 decibels, which should be enough to allow sleep. Unfortunately, you can’t totally block the sound of snoring because the bones of the skull conduct sound to your inner ear.

Snoring usually occurs when you draw a breath in, not when you’re breathing out. Several soft tissues create the noises associated with snoring, including

Your throat

Your throat

Your soft palate (the roof of your mouth)

Your soft palate (the roof of your mouth)

Your uvula

Your uvula

The uvula is the long piece of soft tissue that hangs from the back of your soft palate down into your throat. When an opera singer hits a high C in a cartoon and the camera zooms into her open mouth, that funny-looking piece of flesh you see vibrating is the uvula. You can see your own uvula just by tilting your head back, opening your mouth, and looking at a mirror. If you can’t see it over the horizon of your tongue, you may have a more serious problem. (This condition, called low set soft palate, is commonly associated with obstructive sleep apnea.)

Although common snoring can be annoying and may have even caused a few relationships to fail, it’s generally not dangerous to your health (unless your bedmate tries to keep you from snoring by holding a pillow over your face, or if you slept in the same hotel as John Wesley Hardin, the notorious Texas outlaw who shot a man in a hotel room in Abilene, Kansas, just because he was snoring).

Sleep apnea is a different story. Sleep apnea is a potentially life-threatening condition in which people stop breathing dozens, even hundreds, of times each night. In obstructive sleep apnea, the soft tissue collapses, completely blocking airflow from both the nasal and oral passages for periods ranging from 10 seconds to more than a minute, which prevents oxygen from reaching the lungs. When you experience a fully obstructive event, you and those around you don’t hear anything because no air is moving, so nothing is vibrating. You’re struggling to breathe against a closed airway. When your struggle to breathe finally produces an arousal or awakening, you voluntarily open your airway. Then you take some explosive breaths followed by a return to snoring until the next airway blockage occurs. In central sleep apnea, the airway is open, but you don’t attempt to draw in a breath because the mechanism that regulates your breathing has temporarily failed.

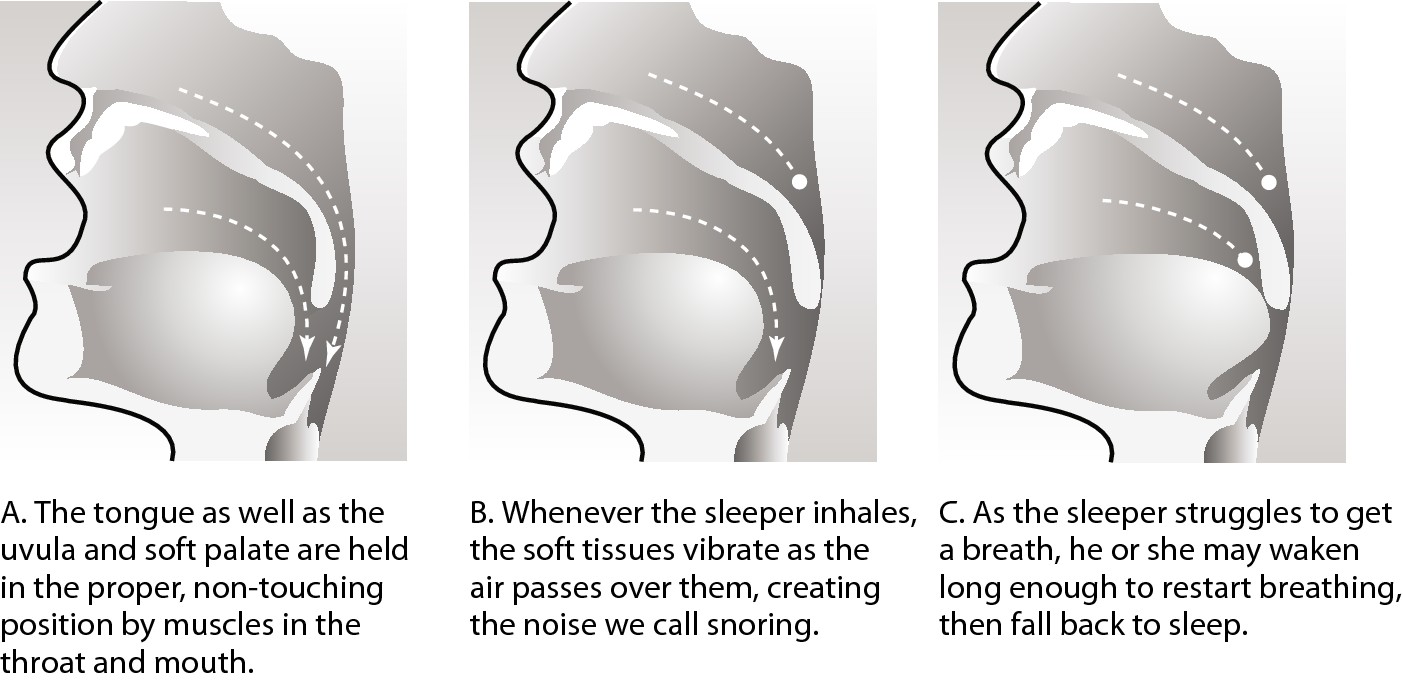

Snoring affects breathing in many ways. In normal breathing (see Figure 9-1a), air flows to the lungs primarily through the nose but can also come in through the mouth. When something causes the soft palate and uvula to collapse into the airway, they touch the back of the throat and shut off the airflow through the nose, which forces the sleeper to switch to mouth breathing (see Figure 9-1b).

In sleep apnea, airflow from both the nose and the mouth are completely blocked by the soft tissue collapse, preventing oxygen from reaching the lungs (see Figure 9-1c).

|

Figure 9-1: How snoring affects breathing. |

|

To help you distinguish between ordinary and dangerous snoring, we review some common causes of everyday snoring and then take a look at what causes the thunderous snoring associated with sleep apnea.

Considering some causes

One night you wake up because someone has just started a chain saw next to your head, and discover your charming bedmate, the one who’s never snored before, sawing logs in bed. Of course, he’s still sound asleep, but you’re now wide-awake. His snoring is so loud that you’re not likely to get back to the Land of Nod unless you move to another room. How could someone who never snored before suddenly start snoring? Several different conditions — both simple and more complex — can cause snoring, including

Breathing problems (from allergies or a cold)

Breathing problems (from allergies or a cold)

A structural problem inside the nose

A structural problem inside the nose

Tonsils and adenoids infections

Tonsils and adenoids infections

A significant weight gain

A significant weight gain

Sleeping on your back

Sleeping on your back

Alcohol and cigarette use

Alcohol and cigarette use

Certain medications

Certain medications

Getting older

Getting older

Before you can take effective steps to stop the snoring, first figure out what’s causing it. We discuss the most common causes of ordinary snoring in the following sections.

Sniffling and sneezing

Any sort of head congestion, whether caused by a common cold or allergies, can lead to snoring. If you’ve been sniffling and sneezing all day, chances are your nose is stopped up, and your nasal passages are swollen, which forces you to breathe through your mouth instead of your nose. Any time you breathe through your mouth, your odds of snoring increase dramatically, particularly if you have a significant amount of congestion inside your breathing passages.

You can end this sort of snoring by clearing your nasal passages so you can breathe through your nose. If you have allergies, ask your doctor for a prescription that clears nose and throat congestion and shrinks swollen tissues so that you may breathe normally during sleep.

If you have a head cold, ask your pharmacist to suggest an over-the-counter (OTC) decongestant.

.jpg)

Living with a crooked nose

Approximately 12 million Americans have deviated septums, which means that the cartilage wall separating the nasal passages has shifted away from the midline to one side or the other. The unevenness in the size of the nasal passages can make breathing through the nose more difficult, and sometimes even causes snoring.

Physical trauma can produce a deviated septum, but it doesn’t have to be a barroom brawl. Babies can even suffer a deviated septum when they make the rigorous passage through the birth canal. But many people aren’t aware that they have the condition, especially when their nose looks normal. (People who have obviously crooked noses resulting from trauma can be fairly positive that they have a deviated septum.)

Left untreated, the condition can lead to chronic nasal congestion and even sinus infections. You can treat a mild deviation with nasal strips to hold the narrowed passage open during sleep. More serious deviations require surgical correction using a procedure called a septoplasty. (See “Considering surgery” later in this chapter for more details on septoplasty.) Depending upon the individual circumstances, doctors may either reposition the septum or remove the portion that is causing the blockage. Septoplasty puts an end to snoring caused by a deviated septum (but not snoring caused by other factors).

Growing pains — tonsils and adenoids

If you managed to get through your childhood without undergoing a tonsillectomy, congratulations. You’re one of the few adults who still have your tonsils. However, infected and enlarged tonsils and adenoids can make you snore. So you may need a tonsillectomy after all, only this time, your mommy won’t sneak ice cream into your hospital room.

Weighing in

If you didn’t have enough to worry about already, extra weight can also cause snoring. As you gain weight, your body deposits excess fat wherever it can find a storage place, including in your throat’s lining. As the fat deposits increase, your breathing passages get narrower and narrower, and soon, you start snoring, or worse.

If your snoring is weight-related, you may stop snoring when you lose your excess weight. If you lose weight and don’t stop snoring, then something else is causing your snoring. Schedule an appointment for a physical and ask your doctor to help you pinpoint the problem.

Sleeping in the king’s position

The ancient Egyptians called the supine sleeping position, where people lie on their backs with their arms folded across their chests, the king’s position. Royalty or not, if you sleep on your back, you’re much more likely to snore because the pull of gravity may cause your mouth to drop open, which shifts you from nasal breathing into mouth breathing. Gravity also flattens the airway increasing its tendency to vibrate.

The idea is that if you sleep on your side you won’t snore. Most snorers’ bedmates don’t buy this theory. Snoring can, and does, occur in all sleep positions. Several gadgets are available to keep you from sleeping on your back, many of them variations on the old “tennis ball in the back of your jammies” idea. Try sleeping with a tennis ball in the small of your back, and you quickly find yourself flipping onto your side. Of course, many people keep right on snoring. If you do, you may have sleep apnea. (See the section, “Knowing When Snoring Is Dangerous: Sleep Apnea” later in this chapter for more on sleep apnea.)

Smoking and drinking

No, this paragraph isn’t a lecture. We just give you the facts about smoking and snoring. Smoking irritates your nasal and throat passages, which in turn increases congestion, which — you guessed it — increases the odds of snoring. So, along with all the other health risks associated with smoking, (oops, guess the lecture crept in after all) smoking can make you a snorer.

Drinking alcohol relaxes all your muscles, including your throat muscles, which increases the tissue pliability, which in turn narrows the airway. This now narrower airway that is less rigid can vibrate more as air passes through. The resulting soft-tissue vibration causes snoring.

If you enjoy an evening cocktail and want to decrease the chance that drinking will make you snore, allow at least four hours between the time you have your mai tai, glass of merlot, or home-brewed specialty, and the time you go to bed. That interval gives your body the time it needs to overcome the alcohol’s sedative and muscle relaxant effects before you fall asleep.

Taking pills when you’re ill

Antihistamines increase the possibility of snoring because they dry out your breathing passages. Several snore-stop products rely on the concept of keeping your throat lubricated; antihistamines do just the opposite — they dry you out, so avoid using them in the evening and close to bedtime.

Tranquilizers are another class of medication that can worsen snoring in the same manner as alcohol — they relax your throat muscles, thereby setting up the soft tissue collapse that produces snoring. Talk to your doctor about dosage timing if snoring becomes a problem after you start taking a tranquilizer. You may also want to try another type of tranquilizer to see if it has a less dramatic effect. Tranquilizers also decrease respiratory drive and make it more difficult to awaken a sleeper who has taken them.

Reaching the not-so-golden age

Along with the many other problems and infirmities that can creep up on people as they get older, you can add an increased tendency to snore. Some studies report that by age 65, more than 60 percent of men snore. Essentially, as you age, things begin to sag. Not just on the outside, they can sag on the inside, too. A couple other factors that contribute to geriatric snoring include

Older people tend to weigh more than when they were in their youth and middle age, and, as we mention in this chapter, increased weight can lead to snoring.

Older people tend to weigh more than when they were in their youth and middle age, and, as we mention in this chapter, increased weight can lead to snoring.

As we age, we tend to lose muscle tone and strength. That loss of tone in the throat can lead to the sort of soft-tissue collapse that causes snoring.

As we age, we tend to lose muscle tone and strength. That loss of tone in the throat can lead to the sort of soft-tissue collapse that causes snoring.

Your mouth and throat’s soft tissues may actually droop as you age, once again setting up a condition for snoring. (Hey, you develop three chins, so why wouldn’t your throat tissues also droop?)

Your mouth and throat’s soft tissues may actually droop as you age, once again setting up a condition for snoring. (Hey, you develop three chins, so why wouldn’t your throat tissues also droop?)

You can’t do much to increase the muscle tone in your throat. (You can’t swallow a dumbbell or do crunches with your larynx.) But you can control your weight and try some of the snoring aids we discuss in the next section to see if you can get some relief.

Evaluating your treatment options

More than 300 products available on the market claim to stop or reduce snoring. Some of them work, and some of them are about as effective as snake oil. Because so many different factors can cause snoring, finding what works for you will be a process of trial and error.

.jpg)

Snoring is the cardinal symptom of obstructive sleep apnea. Taking away the sound doesn’t necessarily improve breathing. Treating just the symptom and not the cause can be dangerous because the real pathology continues to develop and worsen. For example, if you have chest pain caused by cardiac ischemia and you treat it with a painkiller, your heart disease will worsen and develop into heart failure. Alternatively, you will have a heart attack. If the snoring is a sign of obstructive sleep apnea, you must have the apnea treated (not just the snoring), or you greatly increase your risk of developing hypertension, heart disease, and/or stroke.

To treat your snoring, you can choose from three main categories — pills, sprays, and devices. You may find that a combination of treatments works best for you, or you may discover that something as simple as a nasal strip gives you all the snoring relief you need to get a restful night’s sleep.

If you watch late-night television or receive e-mail, chances are you’ve seen an advertisement or two for some new miracle product that claims to stop snoring. You can find a number of anti-snoring remedies at any corner drugstore, and your doctor can even prescribe something in certain cases. The question is — do any of them really work? The answer is a qualified yes. Some of these products are effective against common snoring, but no pill or device you can buy in a drug store will help much if sleep apnea is causing your snoring. If your snoring is really loud, get tested for sleep apnea before you waste a lot of money on gadgets or pills.

Popping pills

Snoring treatments in pill form are formulated to tackle snoring’s underlying cause. For example, if you have allergies, you can purchase either a homeopathic or OTC snoring remedy specifically designed to relieve allergic symptoms. Other herbal medications contain ingredients to shrink soft tissue swelling that may contribute to snoring, while still others dissolve secretions in the throat and nasal passages. These formulas presume that you know the reason why you snore and can select a product with ingredients that address that reason.

Spritzing sprays

Sprays to stop snoring are all the rage right now. They work on the premise that people snore because their throats are dry. Snore-stop spray formulas usually contain one or more food grade oils like almond, olive, sesame, or grape seed oil to lubricate the throat, flavored with orange, mint, or lemon extracts. Lubricating sprays also keep soft tissue from sticking together; in other words, they decrease adhesion, which may serve to quiet or reduce snoring. Before you go to bed, you spray three or four bursts of the product in the back of your throat. People who suffer from ordinary snoring report varying degrees of success with these products, but most do experience some relief.

Trying devices

Some inventors really get excited about the subject of snoring because no one has yet invented a 100-percent sure-fire cure. In garage and basement workshops all across the United States, budding entrepreneurs are busy with their jigsaws and blowtorches, trying to come up with the next million-dollar anti-snoring idea.

Look up “anti-snoring device” on the U.S. Patent Office Web site, and you’ll find 50 patents granted for devices ranging from the Snore Reducer Jacket, a sophisticated version of the old tennis ball in the jammies trick, to nasal dilators (breathing strips), to something you paint on your soft tissues to stiffen them up and keep them from vibrating. (Hold the Viagra jokes, please.)

The following sections describe a few anti-snoring devices that are currently popular.

Sleep cushions

Sleep cushions are pillows you strap to your back that force you to sleep on your side or stomach. They’re helpful for the 60 percent of ordinary snorers who only snore while lying on their backs.

Chin straps

Chin straps are adjustable bands you wear around your head at night to keep your mouth from falling open, the idea being that if your mouth stays closed you can’t snore. Although a chin strap may work for some people, other people have discovered the not-so-delicate art of snoring through their noses. If your bedmate doesn’t mind going to bed with someone who looks like he or she just came from a very strange costume party, chin straps may work for you.

Nasal strips

Nasal strips are thin adhesive strips you place over the bridge of your nose to hold your nasal passages open as you sleep. They’re only effective if your snoring is due to nasal obstruction or congestion. So, unless you’re prone to jamming pennies up your nose, save nasal strips for when you have a cold.

Considering oral appliances

Oral appliances are removable devices you wear in your mouth at night to help prevent snoring. You can choose from three primary types of oral appliances:

Mandibular-advancement devices: These devices consist of custom-made retention plates that fit over your upper and lower teeth. The two pieces are welded together. Once in place, the pieces push the lower jaw forward rather forcefully, which keeps the mouth from falling open. At the same time, the pieces open the airway, thereby preventing snoring. Many users report success, but the devices do take getting used to. For some people, the discomfort is so great that they can’t sleep. Adjustable models make finding a comfortable position easier because they advance the jaw gradually over a period of weeks, allowing the muscles time to adjust to the new position and minimizing discomfort.

Mandibular-advancement devices: These devices consist of custom-made retention plates that fit over your upper and lower teeth. The two pieces are welded together. Once in place, the pieces push the lower jaw forward rather forcefully, which keeps the mouth from falling open. At the same time, the pieces open the airway, thereby preventing snoring. Many users report success, but the devices do take getting used to. For some people, the discomfort is so great that they can’t sleep. Adjustable models make finding a comfortable position easier because they advance the jaw gradually over a period of weeks, allowing the muscles time to adjust to the new position and minimizing discomfort.

Tongue-retaining devices: These devices hold the tongue forward with a bar that keeps it from relaxing into the back of the throat and blocking the airway. Do you remember sucking on a coke bottle and then getting your tongue stuck in the bottle? These devices essentially grab your tongue and pull it forward to keep the base of the tongue clear of the airway. But you guessed it: They’re usually quite uncomfortable.

Tongue-retaining devices: These devices hold the tongue forward with a bar that keeps it from relaxing into the back of the throat and blocking the airway. Do you remember sucking on a coke bottle and then getting your tongue stuck in the bottle? These devices essentially grab your tongue and pull it forward to keep the base of the tongue clear of the airway. But you guessed it: They’re usually quite uncomfortable.

Intraoral appliances: These appliances are custom fitted to the snorer’s oral cavity. When in place, they prevent the collapse of the airway by providing rigid support for the soft palate.

Intraoral appliances: These appliances are custom fitted to the snorer’s oral cavity. When in place, they prevent the collapse of the airway by providing rigid support for the soft palate.

Approximately 45 variations of these appliances are currently on the market. A specialized dentist custom-makes these devices for each patient; they cost about the same as a bridge or any custom dental work — in other words, they’re expensive, as much as $2,000. Less expensive oral appliances that are essentially boil-and-bite mouthpieces, similar to those worn by athletes to protect their teeth, are available for about $60.

Considering surgery

If you’ve tried every pill and gadget and nothing stops your snoring, your doctor may suggest surgery to remove or reduce the size of your uvula, soft palate, and surrounding tissues, or to stiffen the tissues with deliberate scarring. A surgeon may perform one of five different procedures:

Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP)

Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP)

Laser-assisted uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (LAUP)

Laser-assisted uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (LAUP)

Somnoplasty

Somnoplasty

Cautery-assisted palatal stiffening operation (CAPSO)

Cautery-assisted palatal stiffening operation (CAPSO)

Snoreplasty

Snoreplasty

.jpg)

Surgery isn’t for everyone. The more invasive surgeries — UPPP and LAUP — have some downsides. You won’t know if the surgery has been successful until the four- to six-week healing period is over. Furthermore, as with all invasive procedures, you do have a risk of infection and/or complications. UPPP and LAUP are both very painful, relatively expensive, and require extended postoperative recuperation; somnoplasty and CAPSO hurt but not as much. No matter which procedure you choose, soft tissue may grow back, and snoring may start again over time, requiring another round of corrective surgery.

All the procedures in the following sections treat palatal snoring that originates in the soft tissues of the palate and upper throat. Patients should be tested thoroughly prior to surgery, preferably with a sleep study. Testing ensures that they’re good candidates for surgery and determines whether they have sleep apnea or just primary snoring.

Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty

Often called UPPP, mostly because no one can pronounce uvulopalatopharyngoplasty, this procedure is expensive, major surgery performed under general anesthesia in a hospital and requires a one- to three-day postoperative hospital stay. Total cost is somewhere in the neighborhood of $10,000 to $12,000. The surgeon uses a scalpel to remove the tonsils, (if they’re still present) along with portions of the uvula, the soft palate, and pharyngeal arches.

Most doctors consider UPPP a last resort because patients suffer severe postoperative pain for four to six weeks, have difficulty eating and swallowing, may experience a change in the timber or quality of their voice, and run a higher-than-usual risk of hemorrhage and infection because the mouth and throat are so richly supplied with both blood and bacteria. If the doctor removes too much tissue, gastric juices can find their way up into the nose, producing a condition called nasal reflux. Most importantly, UPPP is only effective about 30 to 50 percent of the time. Flip a coin; maybe it will work or maybe it will be an unsuccessful surgery.

Laser-assisted uvulopalatopharyngoplasty

Laser-assisted uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (LAUP) is gaining in popularity. The surgeon uses a laser rather than a scalpel to “cook and cut” portions of the soft tissue in the mouth and throat. Because the laser is so hot, it cauterizes the wound as it cuts. When the wound heals and scars form, the new tissue is smaller and stiffer than before and therefore less likely to cause snoring. More than one procedure may be required to achieve best results. LAUP can also cause a permanent change in your voice. Average cost is about $1,500 to $2,000 per procedure.

Somnoplasty

Somnoplasty is outpatient surgery that uses radio frequency ablation (RFA) to reduce the size of soft tissues. The surgeon uses a tiny probe that sends out radio waves that reduce tissue volume by “cooking” selected tissues. As the body absorbs the dead cells, the offending soft tissues shrink in size, which can help reduce snoring. Postoperative complications are minimal, and pain is easily managed with OTC analgesics. The cost is about $500 per treatment, and more than one procedure is required, resulting in a total cost of $2,000 to $2,500. Because radio ablation is a relatively new technique in sleep medicine, smaller hospitals may not have the equipment required to perform somnoplasty.

Cautery-assisted palatal stiffening operation

Cautery-assisted palatal stiffening operation (CAPSO) uses heat to burn or cauterize tissues of the palate. When the palate heals, the resulting scar tissue is stiffer and less likely to cause snoring. Patients experience significant postoperative pain, but far less than with UPPP or LAUP. The surgery is inexpensive, about $150 per treatment, and can be done on an outpatient basis. Postoperative complications are minimal compared to other procedures, and a recent study reported that 92 percent of CAPSO patients reported short-term relief. However beware, CAPSO is an experimental procedure that hasn’t been fully evaluated. Researchers need to conduct more studies on CAPSO’s efficacy and safety before we can recommend it.

Snoreplasty

Injection snoreplasty is another relatively new procedure. An agent is injected into the soft palate to promote scarring and stiffening of the tissue, thereby reducing the noise of snoring. It’s less painful and much less expensive than three of the four previous procedures, $700 to $1,000 for the two required treatments as opposed to thousands for the other options. Initial results are promising.

Knowing When Snoring Is Dangerous: Sleep Apnea

If your bedmate tells you that you snore so loudly that he or she has to sleep in another room, and he or she can still hear you from that room, you may have sleep apnea, a breathing disorder marked by frequent interruptions of breathing during sleep.

During an apnea episode, you completely stop breathing for at least 10 seconds. The struggle to breathe triggers an emergency alert response in your brain. You wake up just enough to open your airway and gasp for breath, and then fall right back asleep, usually without knowing what has happened.

To meet the medical definition of sleep apnea, these episodes must occur at least five times per hour of sleep. Most people with sleep apnea suffer from 20 to 60 such episodes per hour during the night so they wake up feeling unrefreshed. Yet, many sufferers aren’t aware they have a problem.

Until recently, many medical professionals were still in the dark about sleep apnea and its implications for other health problems. Many family and primary care doctors still don’t look for signs of sleep deprivation in their patients who report excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS), and fail to order additional tests when a patient complains that his or her bedmate snores so loudly it shakes the bedroom walls.

You may be saying, “Well, so what if I snore? I’m not going to waste a bunch of time and money getting treated for that!” Think again. Sleep apnea is a life-threatening condition that can lead to a variety of medical problems and even increase your risk of having an accident. And, the longer it goes untreated, the progressively worse it gets. So you may want to get it looked into after all. Today, not tomorrow.

Categorizing sleep apnea

Sleep apnea is classified according to what causes the interruption in breathing. Treatment for the different types of apnea may vary slightly to obtain the best therapeutic results. Three different kinds of sleep apnea exist:

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is the most common type. Sleepers try to breathe but can’t get any air because of a physical obstruction in their upper airway. Essentially, the airway collapses as the sleeper attempts to inhale. To reopen the airway, the sleeper must awaken, which allows for voluntary airway dilation. Snoring is loud, and patients complain of awakenings with choking or gasping and often have daytime sleepiness.

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is the most common type. Sleepers try to breathe but can’t get any air because of a physical obstruction in their upper airway. Essentially, the airway collapses as the sleeper attempts to inhale. To reopen the airway, the sleeper must awaken, which allows for voluntary airway dilation. Snoring is loud, and patients complain of awakenings with choking or gasping and often have daytime sleepiness.

Central sleep apnea (CSA) is less common. In CSA, the airway is open, but the sleeper doesn’t attempt to draw in a breath due to a temporary failure of the mechanism that regulates breathing. Doctors often find CSA in people with heart failure, metabolic conditions, or a history of stroke.

Central sleep apnea (CSA) is less common. In CSA, the airway is open, but the sleeper doesn’t attempt to draw in a breath due to a temporary failure of the mechanism that regulates breathing. Doctors often find CSA in people with heart failure, metabolic conditions, or a history of stroke.

With mixed sleep apnea (MSA), the sleeper has elements of both central and obstructive sleep apnea; however, MSA is essentially an obstructive airway problem.

With mixed sleep apnea (MSA), the sleeper has elements of both central and obstructive sleep apnea; however, MSA is essentially an obstructive airway problem.

Your doctor uses your medical history along with the results of your sleep lab study and complete physical exam to determine the type of sleep apnea you have, which, in turn, determines the course of treatment prescribed.

Wrecking sleep: What sleep apnea does

Sleep apnea can lead to high blood pressure; contribute to pulmonary hypertension, strokes, congestive heart failure, and other cardiovascular diseases; and cause accidents and premature death. It can also make you feel bone tired.

Sleep apnea causes frequent arousals and awakenings.

Sleep apnea causes frequent arousals and awakenings.

The arousals and awakenings make you spend more time in Stage 1 sleep, which is the lightest and least restorative of the sleep stages.

The arousals and awakenings make you spend more time in Stage 1 sleep, which is the lightest and least restorative of the sleep stages.

Sleep apnea significantly decreases the amount of time you spend in Stage 3 and 4 sleep. Stages 3 and 4 are deep, restorative sleep. Miss these stages and you’ll be a bear the next day. Miss them every night and you set yourself up for a host of health problems.

Sleep apnea significantly decreases the amount of time you spend in Stage 3 and 4 sleep. Stages 3 and 4 are deep, restorative sleep. Miss these stages and you’ll be a bear the next day. Miss them every night and you set yourself up for a host of health problems.

Sleep apnea also decreases rapid eye movement (REM) sleep. You dream during REM sleep, so the constant interruptions of sleep apnea also disrupt our dreams. Sleep apnea episodes are most common during REM sleep because the body is in an utterly relaxed state, which can lead to airway blockage.

Sleep apnea also decreases rapid eye movement (REM) sleep. You dream during REM sleep, so the constant interruptions of sleep apnea also disrupt our dreams. Sleep apnea episodes are most common during REM sleep because the body is in an utterly relaxed state, which can lead to airway blockage.

Between apnea episodes, the sleeper snores very loudly. Very loud snoring that can be heard through closed doors and windows is a key symptom of sleep apnea.

.jpg)

Understanding risk factors for sleep apnea

Anyone can have sleep apnea, but certain factors increase your chances of joining the ranks of the power snorers. Your risk is higher if you

Are male: Studies report sleep apnea in 9 to 24 percent of adult men as opposed to just 4 to 15 percent of adult women.

Are male: Studies report sleep apnea in 9 to 24 percent of adult men as opposed to just 4 to 15 percent of adult women.

Are African American: For reasons not yet understood, African Americans have a higher risk of sleep apnea than any other ethnic group.

Are African American: For reasons not yet understood, African Americans have a higher risk of sleep apnea than any other ethnic group.

Are overweight: Although all overweight people have a higher risk, particularly the morbidly obese, people who have what is popularly known as the “pear shape,” who deposit most of their fat around their middles, have a higher incidence of sleep apnea than people whose excess weight is more evenly distributed.

Are overweight: Although all overweight people have a higher risk, particularly the morbidly obese, people who have what is popularly known as the “pear shape,” who deposit most of their fat around their middles, have a higher incidence of sleep apnea than people whose excess weight is more evenly distributed.

Are older than 40: Studies show the prevalence of sleep apnea increases with age, although doctors believe that 2 to 4 percent of all children have the condition as well.

Are older than 40: Studies show the prevalence of sleep apnea increases with age, although doctors believe that 2 to 4 percent of all children have the condition as well.

Are a smoker: Studies suggest that smokers with a two-pack a day habit run a 40 percent higher risk of developing sleep apnea than their non-smoking friends.

Are a smoker: Studies suggest that smokers with a two-pack a day habit run a 40 percent higher risk of developing sleep apnea than their non-smoking friends.

Have a history of chronic respiratory track problems: Conditions like asthma and chronic bronchitis put you at higher risk for the breathing disturbances associated with sleep apnea.

Have a history of chronic respiratory track problems: Conditions like asthma and chronic bronchitis put you at higher risk for the breathing disturbances associated with sleep apnea.

Have sleep apnea in your family: A family history of sleep apnea increases your risk two to four times.

Have sleep apnea in your family: A family history of sleep apnea increases your risk two to four times.

Numerous scientific studies have shown a correlation between neck size and obstructive sleep apnea. Men with necks larger than 17 inches in diameter and women with necks larger than 15.5 inches are more likely to snore and have sleep apnea.

In addition, people with certain physical characteristics in their faces and mouths run a higher risk. They include

A high palate — may be genetic but also can result from bottle feeding, pacifier use, and thumb sucking

A high palate — may be genetic but also can result from bottle feeding, pacifier use, and thumb sucking

Long-face syndrome — people with long faces usually also have high palates

Long-face syndrome — people with long faces usually also have high palates

A receding chin

A receding chin

An overbite

An overbite

A narrow upper jaw

A narrow upper jaw

A large tongue

A large tongue

A large uvula

A large uvula

Excessive soft tissue in the oral cavity

Excessive soft tissue in the oral cavity

.jpg)

Recognizing symptoms of sleep apnea for an accurate diagnosis

Wouldn’t life be better if we all came with warning tags and instruction books we could just take to our doctors? “May be subject to sleep apnea” is one tag that would raise a lot of eyebrows because, as we mentioned, most primary care physicians just aren’t primed to look for sleep disorders. Most people aren’t all that familiar with the symptoms of sleep apnea either, and figuring out that you have a problem can be especially difficult when symptoms appear gradually. (Sleep apnea symptoms usually appear gradually, but can appear suddenly when they result from a traumatic injury.)

Very loud snoring: Sleep apnea produces distinctive snoring. As sleepers repeatedly struggle to reopen their collapsed airways and suck in great gulps of air, they produce an amazing assortment of gasps, gurgles, wheezes, alarming choking noises, grunts, and of course, snores. But these aren’t just any old snores; these are loud snores — snores that other people can hear and feel all over the house, snores that even your neighbors can hear with the windows closed.

Very loud snoring: Sleep apnea produces distinctive snoring. As sleepers repeatedly struggle to reopen their collapsed airways and suck in great gulps of air, they produce an amazing assortment of gasps, gurgles, wheezes, alarming choking noises, grunts, and of course, snores. But these aren’t just any old snores; these are loud snores — snores that other people can hear and feel all over the house, snores that even your neighbors can hear with the windows closed.

Snoring is a sensitive but not specific marker for sleep apnea. That is, 90 percent of people who have sleep apnea snore, but less than 50 percent of snorers have sleep apnea. Therefore, make sure your doctor considers snoring in combination with other signs and symptoms that we cover in the following sections. Also, be aware that some people with medically significant sleep apnea don’t snore.

Excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS): If you wake up feeling like you haven’t slept, or have a tendency to nod off whenever you get still and quiet for a few minutes (say, at your desk at work especially after a large lunch, in business meetings, and even at the movies), not only is it embarrassing (and potentially detrimental to your career), but also another good clue that you may have sleep apnea. If EDS becomes severe enough, a person may inadvertently fall asleep without warning, which can be extremely dangerous, especially if the individual is operating heavy equipment (like an automobile).

Excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS): If you wake up feeling like you haven’t slept, or have a tendency to nod off whenever you get still and quiet for a few minutes (say, at your desk at work especially after a large lunch, in business meetings, and even at the movies), not only is it embarrassing (and potentially detrimental to your career), but also another good clue that you may have sleep apnea. If EDS becomes severe enough, a person may inadvertently fall asleep without warning, which can be extremely dangerous, especially if the individual is operating heavy equipment (like an automobile).

Interrupted breathing: If your bedmate tells you that you woke him or her up with your snoring, and then you really woke him or her up when you stopped breathing altogether, you can bet you probably have sleep apnea.

Interrupted breathing: If your bedmate tells you that you woke him or her up with your snoring, and then you really woke him or her up when you stopped breathing altogether, you can bet you probably have sleep apnea.

Decreased daytime alertness: If you’re normally a pretty sharp tack, but realize you’re no longer as alert as you used to be, you may be suffering from sleep apnea, especially if you have one or more other symptoms. Decreased alertness makes you more prone to accidents and more frequent mistakes, memory loss, and instances of impaired judgment.

Decreased daytime alertness: If you’re normally a pretty sharp tack, but realize you’re no longer as alert as you used to be, you may be suffering from sleep apnea, especially if you have one or more other symptoms. Decreased alertness makes you more prone to accidents and more frequent mistakes, memory loss, and instances of impaired judgment.

Morning headaches: Morning headaches may be caused by serious oxygen deprivation occurring late in the night when most of your REM sleep is occurring.

Morning headaches: Morning headaches may be caused by serious oxygen deprivation occurring late in the night when most of your REM sleep is occurring.

Dry mouth: If you wake up with a dry mouth, you’ve been breathing through your mouth for an extended period overnight, which could be an indication of sleep apnea.

Dry mouth: If you wake up with a dry mouth, you’ve been breathing through your mouth for an extended period overnight, which could be an indication of sleep apnea.

Hypertension: By itself, high blood pressure doesn’t automatically mean you have sleep apnea. But if you have several other symptoms and then develop high blood pressure, that’s a red flag telling you your cardiovascular system is working overtime every night. If your blood pressure is higher when you awaken than when you go to bed, you may have sleep apnea. Normally, your blood pressure falls, not rises, when you sleep.

Hypertension: By itself, high blood pressure doesn’t automatically mean you have sleep apnea. But if you have several other symptoms and then develop high blood pressure, that’s a red flag telling you your cardiovascular system is working overtime every night. If your blood pressure is higher when you awaken than when you go to bed, you may have sleep apnea. Normally, your blood pressure falls, not rises, when you sleep.

Nighttime heartburn: If you experience heartburn during the night or upon waking, you may have sleep apnea. The attempt to breathe against a closed airway increases pressure in your chest, which forces the contents of the stomach upward. If this happens continuously, the soft tissue valves that prevent gastric juices from flowing backwards may fail, and you’ll have acid reflux in your throat and mouth. The result isn’t just a bad taste, but a fit of coughing and possibly spasms of your larynx.

Nighttime heartburn: If you experience heartburn during the night or upon waking, you may have sleep apnea. The attempt to breathe against a closed airway increases pressure in your chest, which forces the contents of the stomach upward. If this happens continuously, the soft tissue valves that prevent gastric juices from flowing backwards may fail, and you’ll have acid reflux in your throat and mouth. The result isn’t just a bad taste, but a fit of coughing and possibly spasms of your larynx.

Choking feeling: Stomach acid washing up into the throat can cause a choking feeling. Also, stomach acid irritates the collapsed airway, which can cause it to open with choking and gasping.

Choking feeling: Stomach acid washing up into the throat can cause a choking feeling. Also, stomach acid irritates the collapsed airway, which can cause it to open with choking and gasping.

Night sweats: The struggle to breathe against a closed airway requires much more effort than proper breathing. This strenuous effort may produce extensive sweating (hyperhydrosis), especially around the shoulders and neck. This effort actually provokes repeated awakenings.

Night sweats: The struggle to breathe against a closed airway requires much more effort than proper breathing. This strenuous effort may produce extensive sweating (hyperhydrosis), especially around the shoulders and neck. This effort actually provokes repeated awakenings.

Irregular heartbeat: The repeated oxygen deprivation and negative chest pressure produced when you attempt to breathe against a closed airway caused by sleep apnea can damage your heart and trigger an irregular heartbeat. Continued oxygen deprivation may stimulate the body to overproduce red blood cells, resulting in a condition called polycythemia, which also contributes to right heart failure.

Irregular heartbeat: The repeated oxygen deprivation and negative chest pressure produced when you attempt to breathe against a closed airway caused by sleep apnea can damage your heart and trigger an irregular heartbeat. Continued oxygen deprivation may stimulate the body to overproduce red blood cells, resulting in a condition called polycythemia, which also contributes to right heart failure.

Swollen legs: When you have sleep apnea, your brain never really gets fully rested. It fights an all-night battle every night to keep your tissues suffused with oxygen. When oxygen saturations in your blood drop dangerously low due to sleep apnea, your body shunts blood away from the extremities to the heart and brain to supply these vital organs with the oxygen they need to sustain life. If you’re seriously overweight, this reduced circulation can cause pooling of fluid in your legs, resulting in swollen legs every morning.

Swollen legs: When you have sleep apnea, your brain never really gets fully rested. It fights an all-night battle every night to keep your tissues suffused with oxygen. When oxygen saturations in your blood drop dangerously low due to sleep apnea, your body shunts blood away from the extremities to the heart and brain to supply these vital organs with the oxygen they need to sustain life. If you’re seriously overweight, this reduced circulation can cause pooling of fluid in your legs, resulting in swollen legs every morning.

.jpg)

Frequent nighttime urination: If you wake to urinate more than twice each night, you may be suffering from sleep apnea. Frequent awakenings throughout the night keep the body in a more active state, preventing the normal nighttime slow down in urine production.

Frequent nighttime urination: If you wake to urinate more than twice each night, you may be suffering from sleep apnea. Frequent awakenings throughout the night keep the body in a more active state, preventing the normal nighttime slow down in urine production.

Unusual irritability: Sleep apnea causes ongoing sleep deprivation. Prolonged sleep deprivation can cause profound personality changes and make the most even-tempered person crabby and hard to get along with. (If you’re difficult to get along with anyway, don’t blame it on sleep apnea — not unless you snore, too.)

Unusual irritability: Sleep apnea causes ongoing sleep deprivation. Prolonged sleep deprivation can cause profound personality changes and make the most even-tempered person crabby and hard to get along with. (If you’re difficult to get along with anyway, don’t blame it on sleep apnea — not unless you snore, too.)

Memory problems: People who are chronically sleep deprived may experience memory problems. Although memory lapses alone don’t indicate a potential diagnosis of sleep apnea, if you experience memory problems along with several other sleep apnea symptoms, your forgetfulness is probably due to the sleep apnea.

Memory problems: People who are chronically sleep deprived may experience memory problems. Although memory lapses alone don’t indicate a potential diagnosis of sleep apnea, if you experience memory problems along with several other sleep apnea symptoms, your forgetfulness is probably due to the sleep apnea.

If you have two or more of these symptoms, consult your primary care physician (PCP) about your concerns. Be aware that many PCPs aren’t fully informed about sleep apnea and how it affects your health. You may have to be persistent to get the specialist referrals and tests you need for a diagnosis.

Diagnosing sleep apnea

To obtain an accurate diagnosis of sleep apnea, you must undergo a sleep study in a sleep lab, and only a specialist may order this study. (See Chapter 3 for more information on sleep studies.) A sleep study is the only way to get a 100-percent-accurate diagnosis, because such studies offer scientific proof that you’re experiencing episodes of sleep apnea while you’re sleeping.

If you’re considering surgery to reduce snoring, a sleep study is almost obligatory. Some kinds of surgery can make sleep apnea worse, so you really need to know if your snoring is caused by sleep apnea or something else before you decide on surgery. Worse yet, surgery may successfully eliminate the snoring but not the sleep apnea, meaning you have treated the symptom but not the condition. Undiagnosed sleep apnea grows steadily worse; if you “cure” the symptom of snoring but don’t treat the underlying cause, you may ultimately suffer a deadly consequence like a heart attack or stroke. A sleep study gives your doctor a clear assessment of your symptoms, and that helps to increase the accuracy of your diagnosis.

Snoring trivia

The following table compares snoring with some other familiar noises.

Can you believe that only a jet taking off and a rock concert are louder than a snorer with sleep apnea? If you sleep next to someone who has sleep apnea, your answer is probably yes.

Treating sleep apnea

As far as doctors are concerned, the treatment of choice for sleep apnea patients is continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP). CPAP blows air into the sleeper’s airway through a mask fitted over the nose or the nose and mouth, forcing the airway to stay open and eliminating both snoring and apneic episodes. The trouble is that some patients don’t like CPAP nearly as

much as their doctors do, complaining that the mask is uncomfortable and heavy, or that they can’t sleep with the whooshing noise of the machine by their bed or with that blast of cold air blowing against their faces all night long. As effective as this treatment is, only 50 percent of sleep apnea patients actually stick with it.

.jpg)

Asleep at the wheel

Have you ever dozed off momentarily when driving, drifted into another lane without realizing what you were doing, or hit a rumble strip on the edge of the highway that quickly alerted you? If so, pull off the road immediately until you feel more alert. You just had a near-death experience. You’re dangerously sleepy, and because of your slowed reaction time, decreased awareness, and impaired judgment, you’re an accident waiting to happen.

The National Highway Traffic Safety Administra-tion cites driver drowsiness as a factor in 4 percent of all fatal traffic accidents. Pull over at a rest area or parking lot, take a nap in your car, call someone to come get you, or do something to keep from getting back on the road in such a sleep-deprived state.

Doctors have worked with medical equipment companies to develop CPAP machines that are quieter and CPAP masks that are more comfortable. CPAP is such an effective treatment for sleep apnea that even if a patient fails to use it properly at first, the doctor will keep tweaking the treatment in hopes of finding the right combination of mask and machine to help the patient stick with the therapy. Compared to other treatment options, CPAP is cost-effective, painless, non-invasive, and works well.

Some patients still don’t use CPAP no matter what their doctors try. So what are the options for patients who don’t like CPAP? Surgery and oral appliances. Surgery isn’t necessarily the best choice for sleep apnea patients; some surgical procedures may actually worsen symptoms, and the benefits of surgery aren’t always permanent. (For a complete expla- nation of surgical techniques, see “Considering surgery” earlier in this chapter.)

The use of oral appliances is growing in popularity, particularly the mandibular- advancement device. Recent studies have shown that mandibular-advancement devices can help open airways and restore normal breathing for people with mild or moderate obstructive sleep apnea. Just remember that “helped” doesn’t necessarily mean well treated. These devices may reduce apnea by 50 percent, but episodes of breathing problems can still be significant enough to cause other health problems.

When doctors prescribe custom-made devices of the adjustable type, patient compliance is high because the device doesn’t make them uncomfortable, is easy to use, and actually works to stop the patient’s snoring and eliminate or reduce apneic episodes.

Your doctor can work with you to find an effective treatment you like and can use consistently. The important thing is to get diagnosed. Sleep apnea is dangerous. Left untreated, it can kill you.